The recent death of Lt. William Calley, who perpetrated the My Lai Massacre in 1968, is an apt reminder of what the almost forgotten Vietnam War was about.

If truth is the first casualty in war, memory may be the last. Lies about a mythical attack on an American ship in the Gulf of Tonkin, lies about how we were winning when we never were, lies about who we were bombing and where. Lies piled on one another like dead bodies.

Here is what happened at My Lai on March 16 of that year. Lieutenant Calley led over 100 men into a small inland hamlet halfway up the eastern coast of South Vietnam. Calley’s orders from his superiors were ambiguous, but the idea was that anyone in the hamlet, including women, old men, and children—even babies— might be Vietcong or sympathizers, which meant communists. When Calley’s platoon arrived, they saw that no one in My Lai was armed. No soldiers were there at all. American troops met no resistance.

The victims were herded into ditches, or taken to the village center, and shot. After hearing from her son, one GI’s mother recalled, “I sent them a good boy and they made him a murderer.” Some villagers refused to come out of their huts; they were killed by grenades or bursts of gunfire. Children and infants were bayoneted and shot. Corpses were found with the name of Calley’s unit carved into their bodies.

An Army photographer took pictures of this killing orgy, so there was visual evidence and no doubt about what went on. Within less than four hours, the Americans estimated, they had killed 347 people. A body count. Calley himself drove cowering villagers into a ditch, then shot them. He ordered his troops to do the same. Witnesses said he shot a praying Buddhist monk. When Calley saw a young boy crawl out of the ditch, he threw the child back in and shot him. We’ve forgotten this; the Vietnamese haven’t. Their memorial at the site of My Lai today lists the names of 504 victims, ranging in age from 1 to 82.

Lieutenant Calley, when questioned about what happened at My Lai, said he was only following the orders of his superior officer, Capt. Ernest Medina, who had told him that everyone in My Lai was “the enemy.” Medina denied this and said his order was to kill only those who were armed. Witnesses at Calley’s trial said Medina gave the order to destroy anything that was “walking” or “crawling.” The atrocity was covered up in military reports, which called what happened a successful search-and-destroy mission. The chain of command ignored what had gone on, though two generals did know about it. Gen. William C. Westmoreland, the commander of all American forces in Vietnam, may never even have been told what happened, though some said he praised the American soldiers at My Lai for dealing “a heavy blow” to the Vietcong.

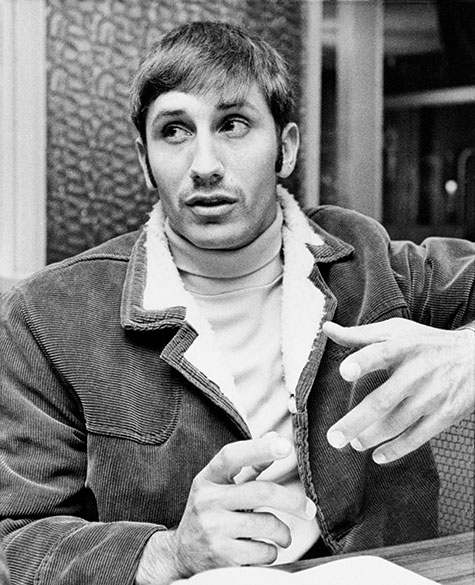

The kind of person Calley himself was helps explain what he could and couldn’t do. He was caught cheating in school and made to repeat the seventh grade. A Floridian, he enrolled in Palm Beach Junior College but dropped out after a semester with failing grades. He found a job as a switchman on the Florida East Coast Railroad, but was arrested on charges of allowing a train to block five downtown intersections in Fort Lauderdale during rush hour. He went west and enlisted in the Army in 1966. After basic training, he was accepted into Officer Candidate School. Despite his low aptitude-test scores, a poor command presence, and a graduation rank near the bottom of his class, he was somehow commissioned as a second lieutenant and sent to Vietnam as a platoon leader. Scraping the bottom of the barrel, the Army knew what it had with Calley, but it needed bodies. Fellow officers considered him an insecure leader, claiming he could barely read a map or a compass. His own troops didn’t respect him, but he was their leader, so they followed him.

The massacre was covered up.

The cover-up might have succeeded and the slaughter never have become known to the American public except for the efforts of one of the most significant whistleblowers in American history. A helicopter gunner named Ronald Ridenhour, who was not at the scene but heard about the killings weeks later, began to do his own probing. Ridenhour interviewed soldiers who had been there. He returned to the United States, and nearly a year after the massacre, he wrote letters to President Richard Nixon, Defense Secretary Melvin Laird, and a number of members of Congress. This sparked an investigation, and after reviewing the photographs and witness testimony, the Army charged Calley with premeditated murder. He had been days away from his scheduled discharge.

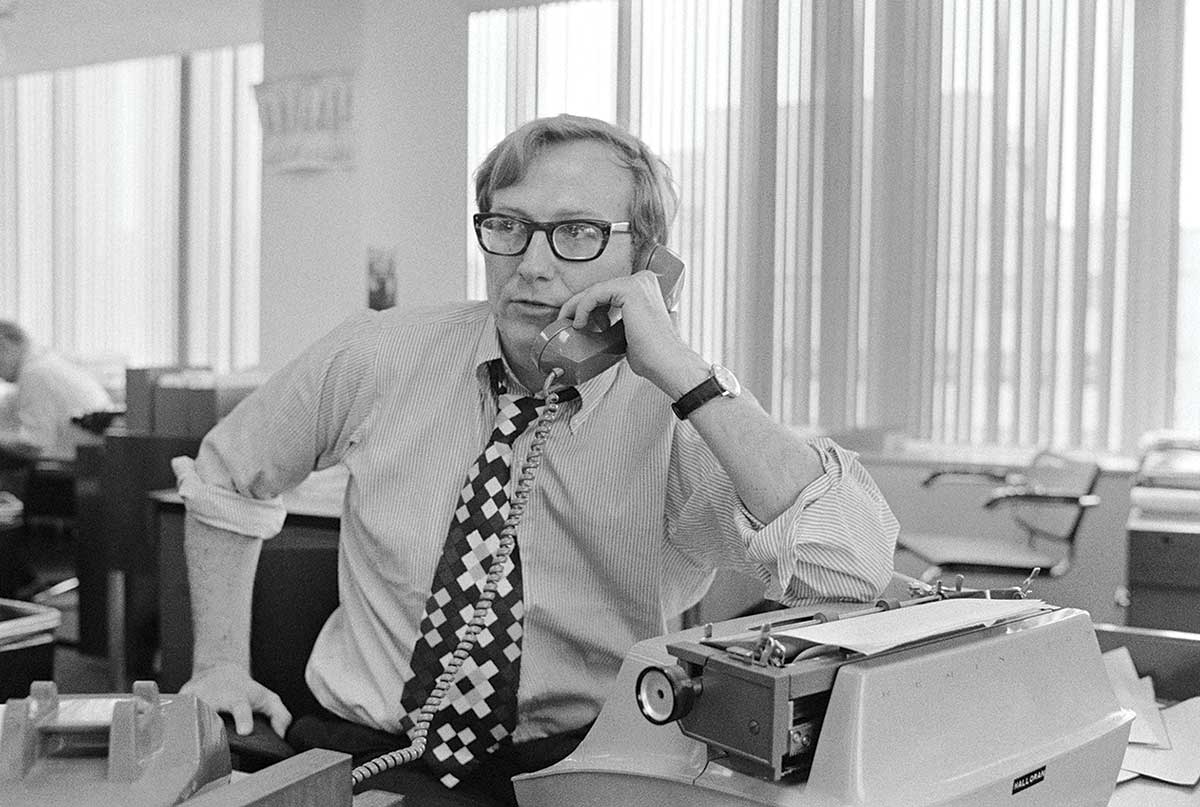

The investigative journalist Seymour Hersh then tracked down Calley where he was being held, interviewed him, and wrote extensively about the massacre. This made the whole country aware of My Lai. Hersh won a Pulitzer Prize for his reports.

The Nation gives a prize every year in Ridenhour’s name.

Captain Medina and two dozen others were charged, but the other cases unraveled before trial or ended with not-guilty verdicts. Only Calley was convicted. He expressed no remorse at his trial and said he’d just been following orders. He was sentenced to life in prison. The commanding general at Fort Benning in Georgia reduced the sentence to 20 years; then the secretary of the Army cut it to 10. A federal judge in Georgia overturned Calley’s conviction, saying he was denied a fair trial because of prejudicial publicity. Calley was confined to his barracks for three months, then released on bail and never returned to custody.

We are much further from the Vietnam War now than World War II was from World War I. We persist in believing we are the indispensable nation, the cop on every beat in the world. So we continue to fight: Iraq, Afghanistan, and who’s next? We seem to be on an endless quest to erase the mistake and failure of Vietnam. In 2003, when I reported on the war in Iraq for The Nation, a major thoroughfare in Sadr City, Baghdad’s huge Shiite slum, had been renamed Vietnam Street. It seemed that the American war against Iraq was going to be won by a noncombatant, Iran, today by far the most powerful country in the region.

In 1972, four years after My Lai, I was in Vietnam when I was invited to a cocktail party in Danang. A fervently anti-communist American philosophy professor, whose husband headed the local branch of Texaco, told me the United States’ biggest mistake had been to withdraw support from Ngo Dinh Diem, the president of South Vietnam, who was assassinated in 1963 when Americans looked favorably on the coup to overthrow him. Diem, she insisted, was a brilliant statesman as well as the second-greatest patriot in what she said was the entire 5,000-year history of Vietnam. I bit: Who, then, was the first-greatest patriot? “Ho Chi Minh,” said this staunch anti-communist without hesitation, referring to the leader of communist North Vietnam. That was when it became pretty clear we didn’t know what we were doing.

In 1973, when I interviewed General Westmoreland, he was retired, a comfortable patrician considering a run for governor in South Carolina. We were on the bank of a river a few miles outside of Charleston, where he lived. Westmoreland spoke about his career, his time in Vietnam, the war itself. Complained about how we were withdrawing troops too fast, still thought we might have won it. As for the Vietnamese people themselves, here is the most important thing he told me: “The Oriental doesn’t put the same high price on life as does the Westerner. Life is plentiful, life is cheap in the Orient, and as the philosophy of the Orient expresses it, life is not important.”

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →In Latin they abbreviate that as QED. The English translation is, That says it all.

More from The Nation

Europe Signs Up for More Humiliation by Trump Europe Signs Up for More Humiliation by Trump

As the post–Cold War order cracks up, the fault lines don’t just run through the Atlantic, but Europe itself.

European Cowardice Is Empowering Trump’s New Imperialism European Cowardice Is Empowering Trump’s New Imperialism

NATO allies don’t want to confront Trump’s aggression. But they may ultimately not have a choice.

The Assassination That Paved the Way for Trump’s Venezuela Attack The Assassination That Paved the Way for Trump’s Venezuela Attack

How Trump’s illegal 2020 killing of Qassem Soleimani—and the West’s indifferent response—laid the groundwork for the brazen abduction of Nicolás Maduro.

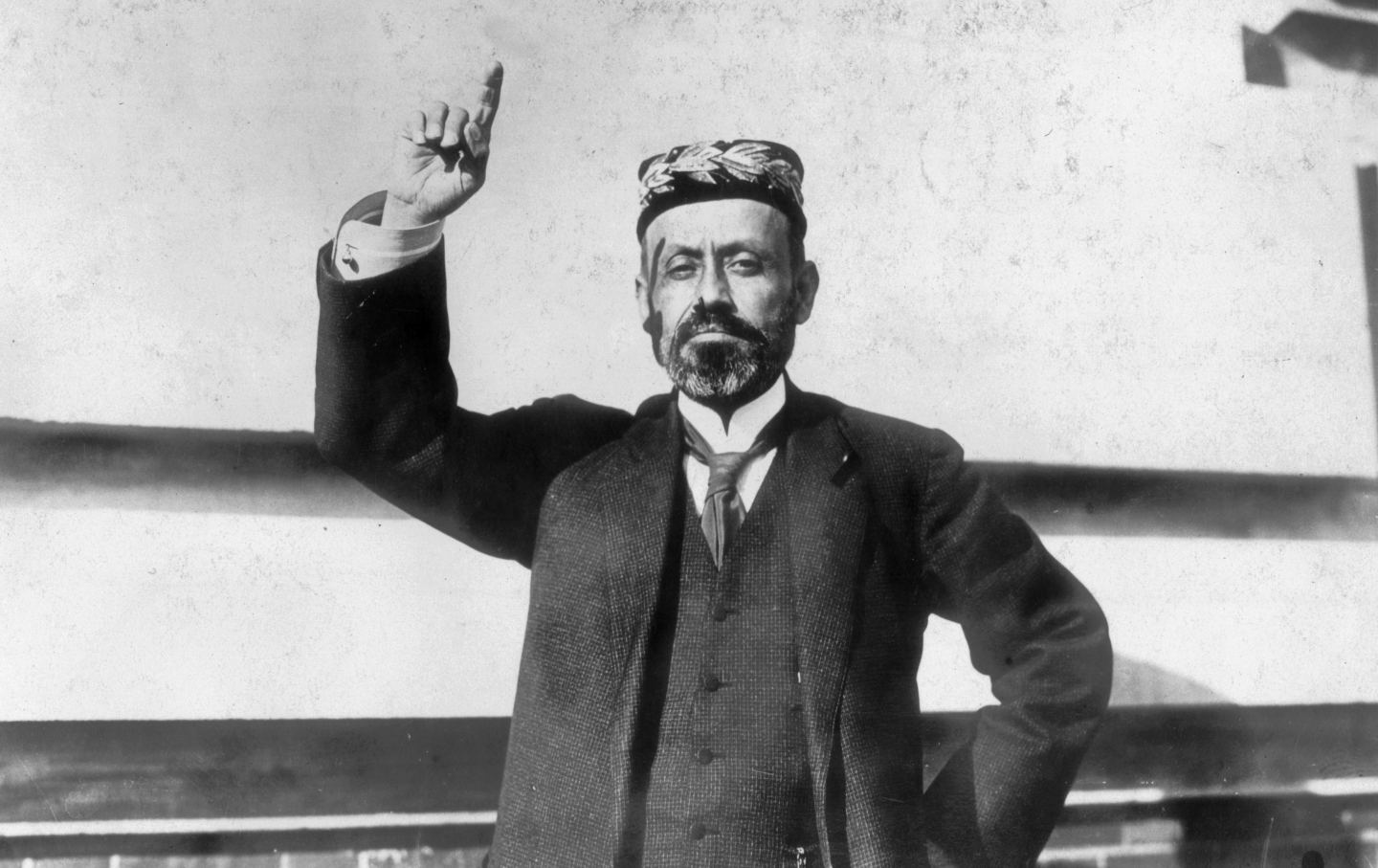

Before There Was Nicolás Maduro, There Was Cipriano Castro Before There Was Nicolás Maduro, There Was Cipriano Castro

Behind today’s headlines is a history of imperial outrage—including a Philadelphia contract man who wreaked havoc in early-20th-century Venezuela and helped oust a president.

The US Is a Rogue State That Deserves to Be Sanctioned The US Is a Rogue State That Deserves to Be Sanctioned

Where is the international outrage over the US assault on Venezuela and kidnapping of Maduro?