I’m a Teacher in Gaza. My Students Are Barely Hanging On.

Between grief, trauma, and years spent away from school, the children I teach are facing enormous challenges.

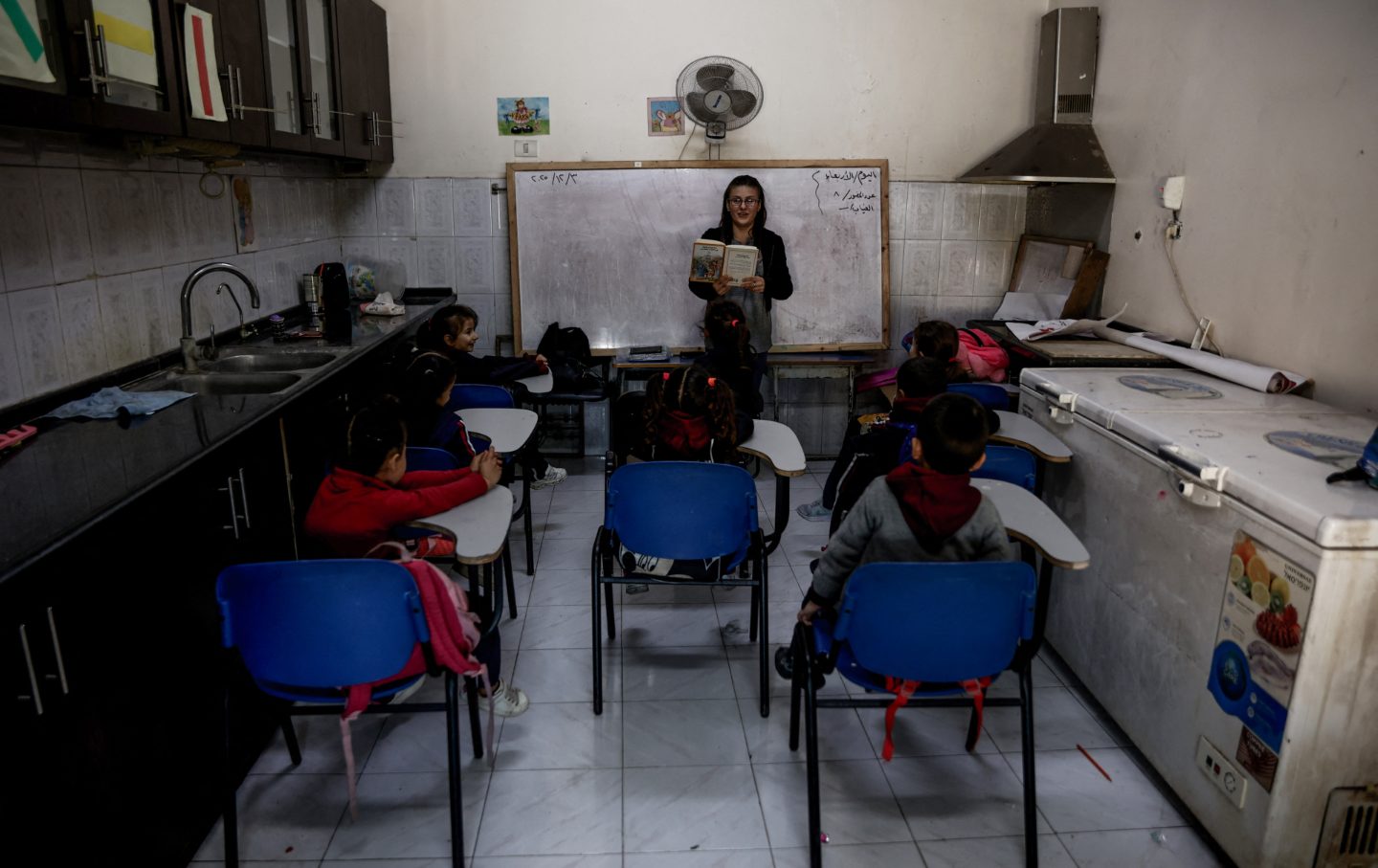

Young learners listen to an educator during the start of classes at Latin Patriarchate School inside the Holy Family Catholic Church compound sheltering displaced Palestinians in Gaza City, on December 3, 2025.

(Omar Al-Qattaa / AFP via Getty Images)It used to be that, every September in Gaza, preparations for the back-to-school season looked much like anywhere else in the world: crowded streets, shop displays of schoolbags and stationery, new designs for school uniforms, and parents filled with excitement for the start of the academic year and the return of routine.

On the first morning of school, the streets were filled with students. Principals and teachers welcomed them at the gates. Children lined up for the morning assembly, enthusiastically doing their exercises before standing in reverence as the Palestinian flag flew above the school stage. Together they sang the national anthem, “Fida’i,” ending with a salute to Palestine’s martyrs and to the prisoners exiled to the darkness of Israeli prisons. The first day also included welcoming activities, introducing students to their classes and new friends, and handing out textbooks.

Since October 7, 2023, however, schools have been closed indefinitely. They have been transformed from places of learning and positive energy into overcrowded shelters for the displaced. The Israeli occupation has not only deprived 660,000 students of their right to education by turning schools into shelters, but has also deliberately targeted school buildings, committing massacres within them. According to the United Nations, 97 percent of Gaza’s school buildings have been destroyed. This includes both government schools and those run by UNRWA. By October 21, 2025, the Palestinian Education Ministry reported the killing of 19,910 students and the injury of more than 30,097 others.

Nearly a year and a half into the war, the private center where I teach reopened its doors to register students. It has become a substitute—or shadow school—for children who have not held a pencil since October 7, and a ray of hope for parents desperate to save their children from the threat of illiteracy.

This center, located in the middle of Gaza, looks nothing like a school. It consists of two large rooms, without lighting or ventilation. The road leading to it is lined with tents, queues for water, and street vendors. The constant buzzing of drones never stops, and at any moment, anyone could be the next target of an air strike.

I teach English at both elementary and secondary levels here. I face challenges on every front—starting with the physical and psychological unsuitability of the space for any real learning. There is no room for young children to practice activities or games. Most have forgotten everything they once knew; many arrive unable to recall even the English alphabet, something we normally teach in kindergarten. Eleventh graders’ knowledge has been frozen since the ninth grade, the level they were in before the war began.

First graders, meanwhile, have never studied in classrooms, never played in a schoolyard, never ridden a school bus in the morning, or heard the sound of a school bell.

They now sit before me with eyes full of hope, carrying schoolbags their parents prepared for them despite the scarcity of resources. Each child comes from a different part of Gaza, most of them displaced, each with their own story of war.

Suzy’s brother told me to keep an eye on her. At only 7 years old, she is still trapped in grief after losing her father, a loss far too heavy for her young age to comprehend. I integrated Suzy with the other children and tried to use interactive and entertaining activities to ease her pain. From what I have observed, children here come not only to learn, but also to escape the war and make new friends.

Sara and Yara’s mother told me that their father has been imprisoned since the beginning of the war. Their father’s absence has caused them trauma, making them resistant to accepting anything easily.

Sidra, a third grader, often arrives late because of the long queues at the bakery. Salim, a fourth grader, missed class one day to sell homemade cinnamon biscuits at a nearby camp. Ahmad, an eleventh grader, told me how his street in Gaza City was besieged and he was trapped in the basement of his house for more than 20 days. Sami, a first grader, said he could not buy an English notebook because his father had lost his job. Jana, a fifth grader, broke down crying because she could not celebrate her birthday—no cake ingredients, no home, no friends to invite.

“What do you imagine your school will look like when it is rebuilt?” I asked them one day.

“A paved yard.”

“Bright colors.”

“A big football field.”

“A garden full of trees.”

“An elevator!”

“And what do you want to be when you grow up?” was my next question.

Ziad said, “A programmer.”

Yazan: “A policeman.”

Rosa: “A dentist.”

Before we could finish the answers, the sound of an explosion shook the area—an air strike on a displaced family’s tent nearby. My student Abood panicked, saying it was close to his home and he needed to check on his family. As his teacher, it was my role to calm him and keep him from leaving until we knew it was safe. He, like the others, could not focus for the rest of the lesson. Then Muhammad, another student, suggested we change the question from “What do you want to be in the future?” to “What is your wish right now?”

When I asked, every single child gave the same answer: “We wish for the war to end.”

This is Gaza—where schools have become military targets, where the morning assembly has been replaced by queues for bread, lentils, and drinking water. The school bell has not rung in three years, and school uniforms lie buried beneath the rubble of homes.

What is happening is not merely a deprivation of education; it is the systematic stripping of an entire generation of its right to a future.

In the wake of the ceasefire, I find myself, as a teacher, facing a mission far greater than just teaching my students English. It is about how I can rebuild their souls and help them regain the passion for life that Israel has taken away from them.

How can children reconcile the sight of their classrooms turned into ashes? There are no school trips, no competitions, and no celebrations for top achievers anymore.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →The war has “ended,” as Trump announced, but here in Gaza, we continue to live through its consequences—details that no one else in the world truly experiences but us.

The day after the ceasefire was declared, my students were not as excited as I had imagined. They were quiet, almost detached, as if the war were still raging inside them. “The Israelis are treacherous,” said Fayez. “They can attack us at any moment.” Fayez added that the truce means nothing to him as long as his house in northern Gaza is destroyed and he can’t go back.

Jowana told me that her father, after losing everything he owned, promised they would leave Gaza once the Rafah crossing opened. Then she whispered, “But Miss, the crossing hasn’t opened yet… Has the war really ended?”

The class ended with a mix of fear, hope, and despair. I saw in their eyes a maturity far beyond their years—two years of war had changed the way they see life.

I try every day to remind my students of their dreams. We begin each class with interactive games to help them release some of their emotional pain. I always tell them that education is our only tool to build a better future in Gaza.

That is why I call on all international institutions and humanitarian organizations to look toward these students—children who have been deprived of their most basic rights. They need both psychological and material support, and above all, they need the chance to continue their education in a safe and healthy environment.

The future and recovery of Gaza depend on investing in its children’s education and emotional well-being—on rebuilding what the war has destroyed both inside them and around them.

More from The Nation

Why the European Left Should Support Peace in Ukraine Why the European Left Should Support Peace in Ukraine

Endorsing a negotiated settlement does not require the left to justify Russia’s invasion or advocate legal recognition of its territorial gains.

Trump’s “Board of Peace” Is Part of a Sordid Anti-Palestinian History Trump’s “Board of Peace” Is Part of a Sordid Anti-Palestinian History

The refusal of those who have held power over Palestine to acknowledge the grievances and aspirations of its indigenous Arab people isn’t new.

Inside Ukraine’s Underground Maternity Wards Inside Ukraine’s Underground Maternity Wards

Four years after Russia invaded, Ukrainian health workers are shoring up maternity care to protect the most vulnerable—and preserve Ukrainian identity.

Gaza Is Still Here Gaza Is Still Here

Despite a “ceasefire,” Israel’s killing has not ended. Neither has the determination of the Palestinian people to survive.

The Ghosts of Colonialism Haunt Our Batteries The Ghosts of Colonialism Haunt Our Batteries

With its cobalt and lithium mines, Congo is powering a new energy revolution. It contains both the worst horrors of modern metal extraction—and the seeds of a more moral economics...

The Repeating History of US Intervention in Venezuela The Repeating History of US Intervention in Venezuela

A look back at The Nation’s 130 years of articles about Venezuela reveals that the more things change, the more they stay the same.