Unmarried to the Mob

After the ex-wife of a Trump Organization insider talked to prosecutors, she lost her children and her home. But she’s still fighting.

Enjoying an outdoor lunch with a friend on a gorgeous day in April, I noticed a woman across the restaurant’s patio lugging around three suitcases and an adorable puppy. She was trying, and failing, to charge her phone at an outlet and was growing increasingly upset. In sweatpants, her frosted blond hair piled on top of her head, she looked like an Upper West Side mom having an extremely rough day. I apologized to my friend for semi-ignoring him as I got more distracted by the plight of the golden retriever, which was alternately straining to get away and trying to comfort its frazzled mama.

“Let me hold on to her while you go inside and do what you need to do,” I eventually pleaded with the woman, as she realized her phone wasn’t charging at the outdoor outlet. She thanked me profusely, left me her four-month-old puppy, Willow, and went inside. Willow tried to eat my friend’s hamburger, but then settled for water and lay down at my feet.

Be it established: I am a dog lover more than a humanitarian. It was only when Willow’s human came back for her, after about 45 minutes, that I recognized her absolute distress. My friend and I asked her if she was OK. She said no. After a bit, she told us through tears that she was a witness in a case against Donald Trump and that she had just been evicted from her apartment around the corner. Suddenly I recognized her. She was the ex-wife of Barry Weisselberg, the son of the Trump Organization’s CFO, Allen Weisselberg. She had provided documents from her divorce to prosecutors and the media. The astonishing September fraud judgment against the Trump Organization, Trump himself, and his two adult sons resulted in sanctions that included Allen Weisselberg.

“You’re Jennifer Weisselberg!” I exclaimed. (Not a humanitarian; definitely a Trump news junkie.) She seemed surprised but gratified that I knew her name. I immediately told her I was a reporter but would keep her plight confidential, unless she said otherwise. She thanked me and explained that she was under a gag order in a child custody battle, so she couldn’t say much—though she hinted that the eviction was retaliation for speaking up against Allen Weisselberg and the Trump Organization’s business practices. She seemed to want to keep talking, so I gave her my phone number. At first, she didn’t call. I kept thinking about Willow. And also, I’ll admit, about the fragile, distraught woman taking care of the dog.

After more than a month, Jennifer reached out to me. Her gag order no longer mattered to her, she said, although she still couldn’t discuss custody issues. She wanted to tell her story.

“I think this article could be important,” she said the first time we met to discuss her plight. “That’s your opening line: ‘Jennifer is homeless!’” The lawyers she worked with in the Manhattan district attorney’s and the New York attorney general’s offices “might say they’ve already tampered” with a witness, she added, referring to the Trump Organization.

Thus began my odyssey of trying to figure out what the hell had happened to her.

Documents from Jennifer Weisselberg’s divorce became relevant to the investigation of the Trump Organization’s finances because of the unusual financial arrangements her father-in-law had set up. Allen Weisselberg had arranged for his extended family to be provided with rent-free luxury apartments, as well as other perks, by the Trump Organization. It was a form of covert compensation to Allen and his son Barry, who also works there, that enabled all parties to avoid taxes. Trump’s son Eric had lived in the same Central Park South building as Barry and Jennifer, and other Trumps lived nearby. Allen and his wife, Hilary, lived rent-free in a luxury Riverside Boulevard apartment from 2005 to 2012. Jennifer says she and Barry socialized with the extended Trump family in New York, at Trump golf resorts, and at his Mar-a-Lago compound. The couple had lovely seats at the 2017 inauguration.

Barry ran Trump’s Wollman Ice Rink in Central Park for 18 years. In the divorce proceedings, he testified that he was provided the Central Park South unit and another dwelling as “corporate apartments” by the Trump Organization. He made in the vicinity of $200,000 a year while he and Jennifer were married—a relatively modest salary for a family of four among New York’s elite. But he lived large on the apartments and other Trump Organization perks. Jennifer could get none of that as part of her divorce. Wollman Rink was removed from Trump’s control by the city in 2021, and, according to Jennifer, Barry now works in a business within Trump Tower.

Barry sued to get custody of their two children, now teenagers, even before Jennifer began cooperating with law enforcement and talking to the media. She was often depicted in the press as a heroic truth-teller, profiled in Air Mail, Fortune, Bloomberg, and The Daily Beast and featured on CNN, MSNBC, and in The New Yorker. Then the Weisselbergs began a semi-public campaign to depict her as an unfit mother.

Jennifer mostly stopped talking. The judge in the custody case imposed a gag order that prevented her from discussing matters related to her children. Now, Jennifer can’t afford a lawyer. She has lost all custody or visitation rights with her children. And she’s lost her home.

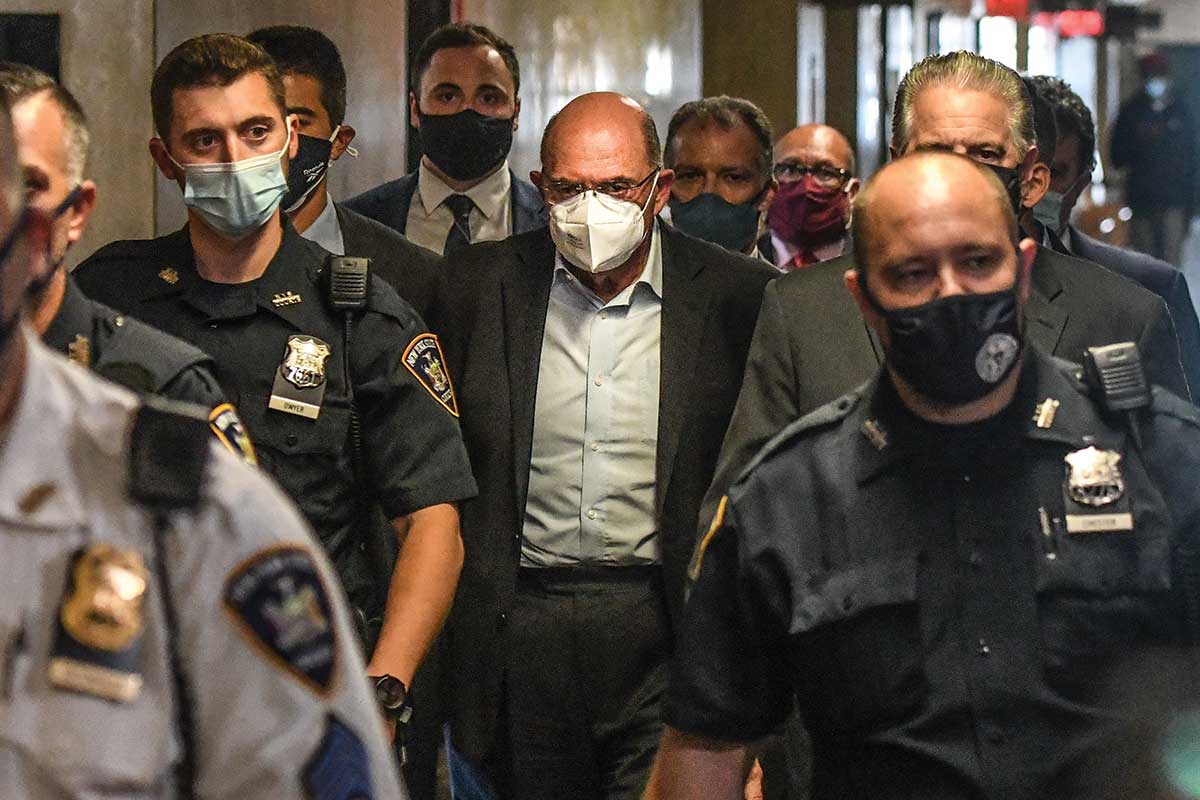

The information she provided on untaxed corporate perks helped convict Allen Weisselberg of business fraud. “The DA was nowhere on that [Trump business tax fraud] before she came along,” says a reporter I spoke to who covered the case early on. “I can’t emphasize that enough.” In addition to serving 100 days on Rikers Island, Allen paid more than $2 million in taxes and penalties on that undisclosed income. The information also helped convict the Trump Organization of tax fraud this year (it was forced to pay $1.6 million, a comparative pittance). Jennifer insists that she’s paying a price for this, that she’s been subject to abusive litigation intended to silence her about not only Allen Weisselberg’s crimes but also Donald Trump’s. Whether or not it’s retaliation, it’s clear that through a crushing barrage of legal actions, lawyers working for the Weisselbergs and for Jennifer’s scandal-plagued former landlord, Stellar Management, have depicted her as a mentally ill person, desperate for her “15 minutes of fame,” who neglected her children and failed to pay her rent.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →It’s obvious that she hasn’t had an easy time. Jennifer will tell you herself: She hasn’t been at her emotionally strongest lately. That was their goal, she says. “Barry told me he wants me homeless, without my kids, so I have to go back to Florida,” where she has family. An old friend, who knew Jennifer before the divorce, told me: “I watched her transition from someone who could stand on her own two feet to…” She paused for words. “Someone who cannot.”

At least one former law enforcement official who worked in the Manhattan DA’s office with Jennifer on the cases involving Allen Weisselberg and the Trump Organization is sympathetic to her claims. The official, who asked to remain anonymous, told me she was “quite reliable on certain subjects” and acknowledges that “she’s been through an awful time.” He adds, “It’s very credible that they’re retaliating against her” for helping with those cases, but he allows that it’s also possible that Jennifer brought some of her misfortune upon herself with questionable decisions.

Whatever else is true, Jennifer and puppy Willow wound up on the streets on April 12. Almost seven months later, she and Willow still have no permanent home.

Jennifer Zarnowiec met Barry Weisselberg in the mid-1990s, when Barry—then an aspiring DJ—came to the Long Island events-planning firm where she worked, looking for a gig. A ballet dancer, choreographer, and actor with music videos to her credit, Jennifer soon began dating Barry and hanging out at the Weisselbergs’ modest home in Wantagh, Long Island. That’s where she met Donald Trump, when he came to visit while the family was sitting shiva for Allen’s mother. The Apprentice star showed the mourners pictures of naked women on his yacht. He also hit on her, Jennifer recalled, though she was already living with Barry in her home in nearby North Bellmore.

“I was just trying to help in the kitchen, but Donald wanted me sitting next to him,” Jennifer recounts. “Nobody protected me—Allen seemed almost proud” that his boss was hitting on his future daughter-in-law.

When she and Barry married in October 2004, Trump attended the wedding with Melania Knauss, who would become his third wife the next year. He gave Barry and Jennifer the Central Park South apartment that would loom large in the cases against Allen and the Trump Organization.

“I thought it was a wedding gift,” she remembers. “I sent him a long thank-you card!” As Barry would later testify, it was actually a “corporate apartment” where they lived for nearly 10 years, paying only for utilities. Then they moved to an Upper West Side apartment building, where Allen paid their rent. The marriage was rocky almost immediately. Jennifer says that she kept up her choreography career when the two were dating and first married, but Barry pressured her to give up outside work once their first child was born. He also abused her physically while they were dating, she stated in court papers, and continued after they had their children. One night in March 2008, Jennifer says, he threw her against a window in their apartment. After a police investigation, she adds, Allen implored her to say she was fine “because he didn’t want Donald to see Barry taken out in handcuffs.” She did what she was told. That incident is among those listed on her application for an order of protection as a domestic violence victim, filed in 2020.

But there were good times, she says. She and her children socialized with Ivanka Trump and her kids, and with Don Jr.’s ex-wife, Vanessa, and their kids. Jennifer also played golf with Trump. “I used to fly on his plane,” she says. “Donald would make me sit with him at the big conference table while Melania just went to bed. He really liked me. Donald became like family to me.”

In 2017, she and Barry, along with his father, attended Trump’s inauguration and traveled to Mar-a-Lago for Presidents’ Day weekend. “It was Ivanka and her kids, Melania and her parents,” Jennifer says. “It was nice, very small.” Allen Weisselberg, she recalls, had to sit in the bar area of the restaurant where they had dinner—he and the president were supposed to keep a distance now that Allen, along with Trump’s adult sons, was running Trump’s business trust, which was set up to limit Trump’s involvement in his sprawling empire. But almost immediately that night, she says, Trump left with his Secret Service detail to meet Allen outside, where they talked for quite a while.

“Donald wasn’t supposed to be talking to Allen because Allen was running the trust, but they were talking all the time,” Jennifer told me. As the probes of both the company and the Weisselbergs heated up in 2021, the two men were instructed to meet only in the presence of a witness, according to The New York Times. She told me (and also, she says, investigators) about hearing Trump and Allen wildly inflate, and at other times deflate, the value of Trump’s holdings, depending on whether they were dealing with tax authorities (deflate) or banks and insurance companies (inflate)—the bottom line of the New York attorney general’s case against him.

Jennifer’s marriage continued to be difficult, but it was not without its tender moments. On Mother’s Day 2017, Barry sent her an effusive card. “I really hope you know what a great Mom you are,” he wrote. “These 2 kids are amazing. Without you they wouldn’t be.” But just a few months after sending that card, Barry filed for divorce, which became final at the end of 2018. Jennifer moved to the Upper West Side apartment from which she was ultimately evicted.

Barry’s divorce deposition, on August 7, 2018, turned out to be a damning document for him, even if it didn’t redound to Jennifer’s financial benefit. He stated, for the legal record, that he’d received “corporate apartments”—untaxed compensation—plus private school tuition payments for his children, which he claimed were made by his father, amounting to $50,000 for each child, totaling around $500,000 for the years 2012 through 2019. It was later revealed that some tuition checks were signed by Donald Trump and other organization officials—more untaxed compensation. Some of that information led to the convictions of his father and the Trump Organization on tax fraud charges. But Barry got lucky: The statute of limitations had run out, and he couldn’t be prosecuted for failing to declare such benefits on his own tax returns.

The deposition included other less-than-flattering details about Barry. He told the lawyers that his father’s credit card was on file at the office of the dentist who cared for him. His father paid his family’s doctor’s bills, his car leases, and fees for his children’s summer camp, Hebrew school, and other activities—all told, an estimated extra $235,000 a year, according to divorce documents. Allen sent Barry multiple gifts of more than $5,000, as well as “financial assistance” when times were tough, Barry told the court. Barry also transferred a bank account he shared with Jennifer, containing at least $37,000 in wedding gifts, to himself, for reasons he couldn’t remember.

Maybe most important, he testified that his father was paying his legal bills in his divorce from Jennifer. Jennifer, meanwhile, often couldn’t afford a divorce attorney on her own.

Jennifer Weisselberg was clearly unlucky when it came to in-laws. But after her divorce, she also happened to have the bad luck to be deposited by her father-in-law into a building owned by one of New York’s most cutthroat real estate magnates: Laurence Gluck, the founder of Stellar Management. With more than 13,000 apartments, Gluck regularly appears on the Right to Counsel NYC Coalition’s list of worst evictors. Gluck is notorious for buying rent-stabilized complexes and using various measures over the years—payoffs, harassment, alleged upgrades—to oust thousands of protected tenants and install those who will pay the market rate. Jennifer rented one of roughly 50 market-rate apartments in the 203-unit Columbus Manor complex on West 93rd Street, a publicly subsidized, rent-stabilized building Gluck had purchased in 2006. When she moved in in 2018, the rent on her unit was $6,050, having jumped from just over $1,300 in 2017, nominally because Stellar Management had turned the reasonably spacious two-bedroom apartment into a small—and, by her description, shabby—three-bedroom. Allen Weisselberg’s choice of landlords was no accident, Jennifer says. Her father-in-law had told her he didn’t want to share his financial information with anyone, and he said Gluck wouldn’t make him. (In 2021, Stellar Management told Business Insider that Weisselberg had produced all the documents required of a guarantor.)

The first housing action against Jennifer does not seem to have been retaliatory: She was cited for nonpayment of rent in July 2020, before she ever spoke to a law enforcement official about Weisselberg or Trump. She often struggled to pay the rent, she admits, as a stay-at-home mom who depended on $9,000 a month in alimony and child support—which she says her ex was not reliably paying. Then, in August of that year, she says, she was contacted by New York District Attorney Cyrus Vance Jr.’s office, which was seeking any information about Trump’s business dealings that she might have obtained in her divorce.

Trump’s Legal Travails

That nonpayment petition, which initiated the eviction proceedings that were brought in October 2020, named Allen Weisselberg as her fellow tenant. Surely her wealthy former father-in-law, as the guarantor of her lease, would have to pay the rent. But that’s not what happened. Columbus Manor’s lawsuit against Allen and Jennifer mysteriously morphed as it went along. The two motions filed at the end of 2020 named Allen as cotenant. In March 2021, Jennifer began talking to the media about the Trump/Weisselberg untaxed compensation issues. The next month, Jennifer was subpoenaed by the DA’s office to provide documents from her divorce. On April 8, she was famously photographed rolling a luggage dolly loaded with boxes of files out of her apartment building.

On April 27, someone—Jennifer says she asked the Columbus Manor leasing office, which said it didn’t know who—paid $91,550 in back rent, wiping out the arrears. On April 29, the landlord’s lawyer, Kevin D. Cullen, “discontinued” the New York County Civil Court action against Jennifer and Allen. On May 14, Cullen’s firm filed another “discontinuance” of the action against Allen and his ex-daughter-in-law.

Three days later, Cullen filed a new eviction proceeding, against Jennifer alone, in state Supreme Court. The stated cause? Her lease had run out on April 30, 2021, and “Defendant’s tenancy was exempt from any form of rent regulation and thus no renewal lease was required,” according to the initial motion filed with the court on May 17. Now there was no mention of rent arrears; Stellar just wanted her out. (Cullen did not reply to multiple requests for comment.)

In May, Stellar moved its eviction action against Jennifer from the New York County Civil Court, which normally handles housing disputes, to the New York County Supreme Court. Stellar also shifted the rationales. In May 2021, the firm claimed Jennifer’s lease had expired, and because her apartment was no longer rent-stabilized, it didn’t have to offer her a new one; two months later, the story changed. Stellar claimed that the action had commenced “following expiration of the lease agreement between the parties. Prior to expiration of the lease, it offered the Defendant a renewal lease. To date, Defendant has failed/refused to sign/accept the offered renewal.”

Jennifer says she was never offered a new lease. She also has no idea why Allen’s name had disappeared from the legal proceedings. I saw her rent bills, addressed to her and Allen—right up until April 2023, when she was evicted. And the guarantor agreement signed by Allen, which I’ve also seen, had no expiration date.

Jennifer was represented by at least three different attorneys in her nearly three-year battle. Running out of money, she wound up defending herself at times, and didn’t do better. In the end, she signed a settlement agreement committing her to pay half her back rent and move out on March 31, 2023. She says she didn’t want it filed, but her attorney at the time filed it anyway.

A respected Manhattan tenant attorney not connected to the Weisselberg cases reviewed the Supreme Court actions with me. He agreed that the case took strange twists, including the move from civil court to the Supreme Court and Allen’s disappearance from the lawsuit. The attorney also noted the shifting explanations for the eviction. But once the stipulation of settlement was filed with the court, signed by Jennifer, the case was over, he told me. The eviction was legal.

Jennifer continued to try to fight it, despite the settlement agreement. But the New York County sheriff finally evicted her and Willow on April 12.

Over in the matrimonial division of the New York County Supreme Court, the Weisselbergs’ custody battle played out in tandem with her eviction fight. As with the eviction, Barry sued for sole custody before his ex-wife was revealed to be cooperating with the authorities.

In February 2020, Barry took their children and refused to return them, according to the order of protection against domestic violence she sought and won (although it was later vacated). She believes he did this at least in part in retaliation for the domestic violence complaints she made against him. “I started to speak out for the first time about his domestic violence, to the police,” she says.

Jennifer did not share many records of the couple’s divorce and custody proceedings with me, saying she was still concerned about the gag order. I’m relying on a deposition from Barry (also a factor in the cases against his father and the Trump Organization); copies of the settlement; the order of protection in the domestic violence case; and a few of the court transcripts.

Their custody battle heated up as Jennifer started making news. On March 19, 2021, she told NBC about her husband’s untaxed corporate apartments and disclosed that she had met multiple times with the DA’s office, saying she was going public in part to try to fight for custody of her children. “I have no reason to be here except that I am not a woman who is willing to live a life of secrecy, out of fear, any longer,” she told NBC’s Tom Winter in an on-camera interview. “They will out-resource me in the courts forever, and I have tried to be graceful, and I have tried to handle this privately. And they are not agreeing to do so at all. What choice do I have?”

That very day, Supreme Court Judge Lori Sattler, handling the divorce and custody matters, issued a gag order prohibiting Jennifer from publicly discussing her children. Court records show that her attorney agreed to the order, although Jennifer has maintained all along that it applied only to the custody fight—not to the tax fraud issues the DA was investigating.

Then, on May 13, the news broke that Allen Weisselberg—and, at some point, Donald Trump and Donald Trump Jr. as well—had signed checks to pay for Barry and Jennifer’s children’s tuition at Columbia Grammar and Preparatory School. News outlets reported that the DA’s office had subpoenaed the school to obtain the family’s tuition records. (Trivia note—or not: Larry Gluck was also on the school’s board, from 2013 through 2016.) It’s not clear whether the tuition information came from the Weisselberg divorce documents, but Jennifer, who did interviews with major media outlets that same week, confirmed the reports.

In response, Barry’s attorneys moved to hold her in contempt of court for violating the order against talking about her children. Jennifer and her attorneys insisted she hadn’t violated the order but had simply told the truth about what turned out to be more illegal compensation to her ex-spouse. At the hearing, one of her attorneys, Aimee Richter, took the opportunity to publicly state Jennifer’s theory of why she was being legally besieged: “The narrative that the Weisselberg family and the Trump Organization are trying to get out there [is] that my client is crazy and that she should be discredited both in this court and in the court of public opinion, and possibly with regard to the investigations that are going on in the district attorney’s office and all the other investigations that are happening.”

But, damaging for Jennifer, Barry’s attorneys revealed at the hearing that a psychiatrist the court had ordered to evaluate her before Barry physically took custody of her children in February 2020 found Jennifer to be “manic psychotic,” and that she’d been taken to Bellevue Hospital in Manhattan during a contentious hearing, none of which I’d known before I saw the transcript. Jennifer told me she was released from Bellevue immediately. “I wasn’t even admitted!” she says. For reasons of privacy, I can’t obtain the official records.

Rob Georges, a lawyer who represented Jennifer in her early dealings with the DA’s office, echoed Aimee Richter’s analysis at the time. “It seemed like she was being treated unfairly. They’re trying to discredit her,” he told The Daily Beast. Almost exactly two years later, Georges told me via text: “I like Jennifer a lot and did my best for her.” She moved on to a new attorney, he said. That attorney no longer represents her and didn’t reply to my requests for comment. Nor did Richter reply to repeated calls and texts. But Barry’s attorney, Peter Stambleck, surprised me by returning my e-mail. “I don’t believe there is really anything to talk about nor do I think such personal matters involving children should be addressed in a public forum,” he wrote, inviting me to ask “general questions about divorce in NY or the like.” When I wrote back and asked why Jennifer received so little in her divorce settlement, he didn’t reply.

Jennifer’s advocate in her domestic violence proceeding, Zoe Applbaum, a volunteer with STEPS to End Family Violence, filed an affidavit on her behalf with Aimee Richter two years ago. “Jennifer is extremely kind, smart, and her strength continuously amazes me as I get to know her better,” Applbaum wrote, but her “PTSD” and “psychological trauma” from her legal battles had taken a toll. Applbaum framed the barrage of legal actions against Jennifer as “abusive litigation,” defined as “the misuse of court proceedings by abusers to harass, intimidate, coerce and/or impoverish survivors.” Custody battles, she said, are a common tool, “portraying the survivor as an unfit and incompetent parent, including making requests for mental health evaluations in an attempt to undermine the survivor.”

In the end, I couldn’t prove that Jennifer’s eviction or her custody troubles represented retaliation for sharing evidence about Trump’s and Weisselberg’s tax fraud. But she was a victim of Trump/Weisselberg fraud nonetheless. Jennifer lived a life of luxury, albeit a troubled one, during her marriage to Barry. That life was made possible by the untaxed compensation Barry earned from the Trump Organization, as well as gifts from his father, Allen. As an ex-wife, Jennifer couldn’t share in any of that.

Their official “marital assets” were meager. Jennifer got half of a 401(k), just under $200,000, which she says she’s using to pay the hotel bills that she’s racked up since her eviction. In New York, a marriage that lasts 15 years—Jennifer and Barry were married for 14—is treated the same as one that lasts a month in terms of spousal maintenance guidelines. Although she hasn’t worked since her children were born, Jennifer’s modest alimony award lasted just four and a half years. It expired at the end of May 2023. Her child support ended when Barry took custody of their children.

By her own admission, Jennifer made some bad decisions. Nevertheless, for a while, she was a hero, a whistleblower. She says she thought speaking out would keep her safe and help her get her kids back. So far, it has not.

The consequences that Trump faces for his perfidy have now moved beyond paying fines for tax fraud. He’s accused of multiple violations of the Espionage Act and obstructing the certification of the 2020 election by the Department of Justice; Fulton County District Attorney Fani Willis has charged him and 18 allies with racketeering, conspiracy, and other offenses related to his efforts to overturn Georgia’s election results; and a judge dissolved many of his New York businesses in late September. Currently, there are 91 felony counts against him. For some people, that makes Jennifer’s travails less important. Yet her story resonates with me. This is a deeply corrupt extended crime family, and she was in it and then tossed out. “You know how, in every mob story, there’s an idiot?” she asked me the last time we met, at my apartment. “That was me.” Still, maybe the real story is how easy it can be, in this city of unscrupulous landlords and deep-pocketed ex-husbands, to end up a divorced, middle-aged mother, with no job, no money, without your children, and ultimately without a home.

The day we spoke, Willow had just turned six months old, in a Lower Manhattan hotel. Jennifer brought birthday hats for Willow and my dog, Sadie. Willow was still struggling, and so was her mama. My conclusion, I told her, is that her eviction was unethical, maybe even retaliatory on some level, but not “illegal.” She believes otherwise. What we agree on is that she was a victim of one of the worst landlords, as well as one of the worst families, the Trumps, that this city of heroes and criminals has produced.

For a few months during the summer, Jennifer stopped returning my calls and texts. The old friend I’d spoken to, who had known her before the divorce, also stopped hearing from her. “This woman put her life on the line for the truth, and I pray she’s safe,” she told me. “Where does help come from for someone like her?”

I heard from Jennifer again in late September, as did her friend. She is safe, but still fragile, temporarily staying with someone close to her outside the city, but wanting to return to Manhattan, to continue fighting to see her kids.

I worried she’d stopped talking to me because she didn’t want to go ahead with this story. No, she says. “I’m afraid for you!” And still afraid, for herself, of the Trump mob. I tell her I’m not afraid—she was calling and even coming in and out of my apartment for almost six months, and I’m fine. (Also, the Trump crime family and friends are a little distracted.)

But the safest thing for both of us, I say, is to get this story out.

She agrees.

More from The Nation

Deportation and the Silence That Follows Deportation and the Silence That Follows

When ICE abducted my father without cause, something strange filled his vacancy.

On Cora Weiss (1934-2025) and Peace On Cora Weiss (1934-2025) and Peace

Cora Weiss died in December at age 91. She never stopped campaigning to save the world from nuclear destruction.

The Media’s Coverage of the Venezuelan Coup Has Been Dreadful The Media’s Coverage of the Venezuelan Coup Has Been Dreadful

War may be the health of state, but it’s death to honest journalism.

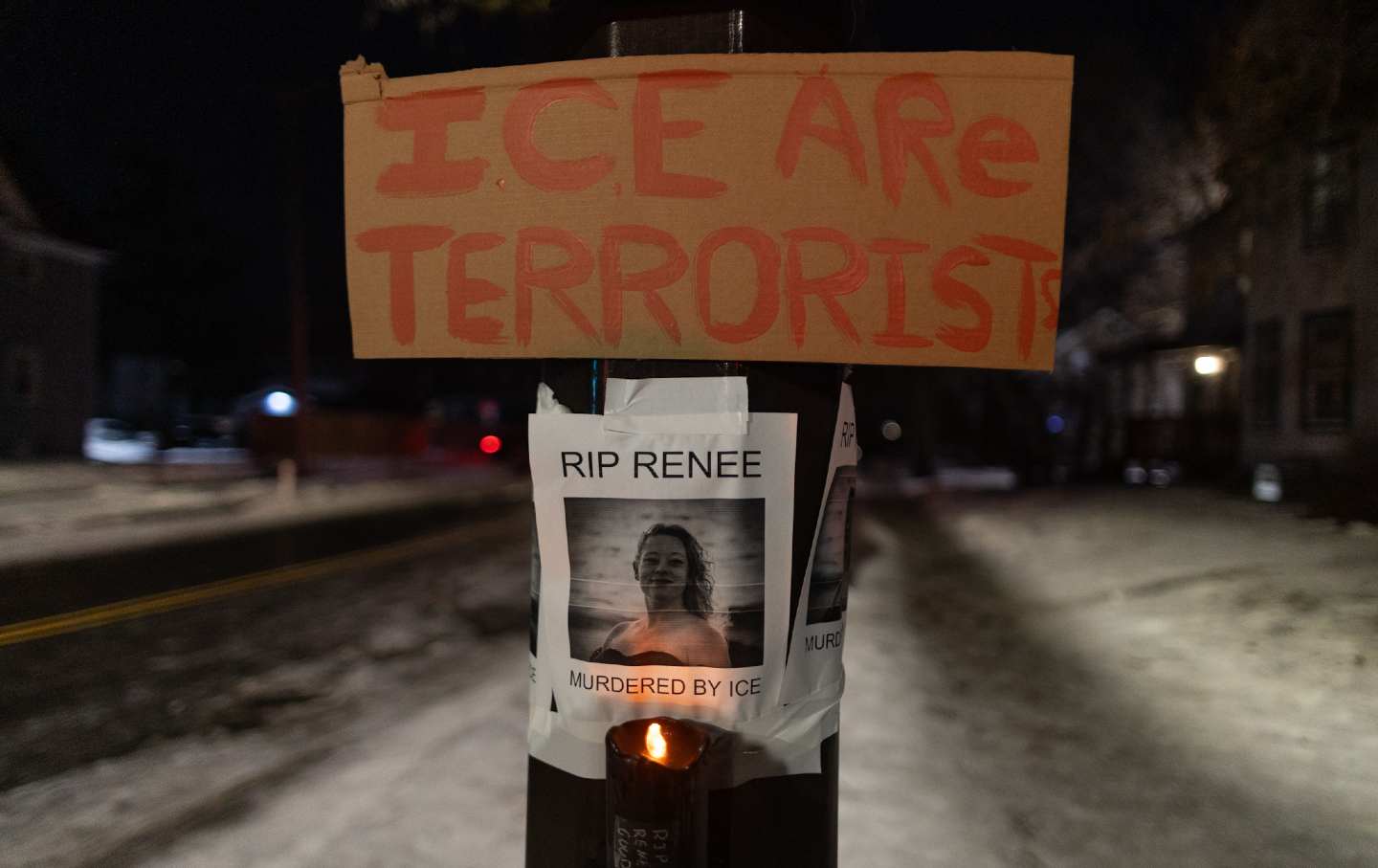

Dismantling the Meme Logic Behind Renee Good’s ICE Execution Dismantling the Meme Logic Behind Renee Good’s ICE Execution

The Trump administration is once more invoking upside-down alibis of state to conjure the bogus specter of imminent threat.

Minneapolis to ICE: Get the Fuck Out! Minneapolis to ICE: Get the Fuck Out!

An ICE agent shot dead Renee Nicole Good. Residents are ready to fight back.

Prosecute Renee Nicole Good’s Murderer Prosecute Renee Nicole Good’s Murderer

The ICE agent who killed Renee Nicole Good not only can be held accountable for murder—he must be.