The Student Movement Is Writing a New Chapter of History

The protesters are building on decades of struggle for Palestine and pulling us all into a radically new future. Suddenly, history is speaking with gusto.

A California Highway Patrol officer detains a protester at UCLA on May 2, 2024.

(Mario Tama / Getty Images)

The eruption of pro-Palestinian protests at universities across the United States—and around the world—was a long time coming. For months, student organizers have faced intense repression from university administrations intent on severely curtailing any pro-Palestine and anti-war political expression on their campuses. This has involved punitive disciplinary procedures resulting in suspensions for low-level infractions, the disbandment of groups such as Students for Justice in Palestine (SJP) and Jewish Voice for Peace (JVP), censorship, and arrest by campus police. Students, largely undeterred, have responded by developing new tactics and modes of expression to ensure that their message is heard and their presence felt, including, most recently, by establishing continuous Gaza solidarity encampments and occupying campus buildings to demand that their institutions divest from Israel.

Still, the speed and scope with which the movement has proliferated in the last few weeks is breathtaking. So is the violence and repression used to try to crush that movement.

Since April 17—when, in a serious escalation of repression, Columbia University brought the New York Police Department in to destroy a student solidarity encampment, similar encampments emerged on campuses from coast to coast (as well as in Canada, Europe, Asia, and Australia). In turn, university administrations, in coordination with police departments, responded with overwhelming force. At least 2,300 students, professors, and solidarity activists have been arrested at nearly 50 schools across over a dozen states. The crackdowns have concentrated student resolve and revitalized a solidarity movement frustrated by a lack of progress. Palestinians in Gaza have heralded the activism, dubbing it the “Student Intifada” and calling on students worldwide to escalate their protests.

The language and tactics of organizers have become objects of obsession for elite media, as commentators compete with each other to produce inane theories for why students are so worked up. Ironically, these commentators universally overlook their own role in the ecosystem of campus activism. The panic that pundits foment has led to pressure from the donors and trustees who effectively control universities these days. Students have then seen the power of both their message and the forces opposed to them—an ideologically and tactically radicalizing experience. In turn, students have increased their militancy, and a growing number of encampments have expanded into occupations of university buildings. This has sparked more panic and more repression. Having lost the deterrent power they hold as disciplinarians, administrators are just throwing more fuel on the fire.

Contrary to the preferred media narratives, left-wing views spread among students not through social contagion nor through professorial indoctrination. Rather, it is through the often new experience of confronting institutional power with sensible, morally obvious demands—such as, for instance, the demand that your university cut financial ties to a country carrying out a genocide—and being rebuffed, repressed, and ostracized in return, that young people develop critical worldviews. In other words, it is neither special brilliance nor special naivety that produces revolutionary students. It is the condition of being positioned within powerful institutions and discovering that agitating for justice totally disrupts their core function—ruling class reproduction.

This cycle is familiar to me, and not just through my role as an attorney at Palestine Legal, where I have helped Palestine solidarity activists and groups navigate the post–October 7 McCarthyite wave of repression. I lived it myself as a college student over a decade ago.

When I arrived at Tufts University in the fall of 2011, I was a liberal. Born to a Palestinian father and a Jewish mother in 1993, I was an Oslo baby in the truest sense. Despite the historical collapse of that era into the Second Intifada and subsequently the onset of the blockade on Gaza, I held tight to its promise—namely that, through effective communication and tough negotiation, peace could prevail.

Suffice to say, I was quickly disabused of these views. In my freshman year, I joined the Tufts chapter of SJP, which had been formed on campus the year before. There were maybe a dozen of us in the group. After some deliberation, we decided to host an “Israeli Apartheid Week” in the spring semester, during which we would program films, speaking events, and a demonstration to draw attention to the plight of the Palestinians living in the 1948 territories, the West Bank, and Gaza, and as refugees. I saw this as a way to advance the universalist principles core to my political identity. To my mind, we were simply calling for equal rights for Palestinians and Jews in the land between the Mediterranean Sea and the Jordan River, as well as the right to return for Palestinians dispossessed in 1948. The framework of apartheid, which centers inequality before the law, was an attempt to leverage this liberal discourse.

Though nothing like what today’s students are facing, we were met with a degree of backlash—from administrators and peers—that was staggering. Members of our group were accosted and screamed at by senior faculty, the administration attempted to revoke our permission to use common space, and we were accused by fellow students of antisemitism and supporting terrorism. The level of vitriol directed at us was isolating, but also illuminating. It led me to realize that, contrary to what I had assumed, the force between us and justice was not unreason but power.

Our group evolved, and we sharpened our analysis. We began to target Tufts itself, and to demand divestment from Israel. Our power grew too—as we shifted from issue-based public education to political organizing, we built connections with other social justice groups, and our ranks swelled. By my senior year, the Ferguson uprising and the first iteration of Black Lives Matter had arrived, and SJP was tactically and politically prepared for the moment. We engaged in direct actions and street occupations alongside other anti-racist student groups to demand an end to police violence. We were publicly derided, but we built strong and lasting relationships and profoundly influenced discourse on and off campus.

Many of today’s student activists have experienced a version of this historical sequence. After cutting their teeth on the 2020 George Floyd uprisings, they are now prepared to organize for Palestine with political and tactical sophistication.

But where, during my college experience, history was clearing its throat, it now speaks with gusto.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →The stakes are much higher now than when I was in college. The genocide against Palestinians in Gaza is already a world-historical crime, and the looming invasion of Rafah promises a new magnitude of horror, all of which has motivated students to make sacrifices they might not have otherwise. And the repression they face is far more extreme, with universities directing state violence on their campuses without qualms.

From my vantage, I can trace the distance between these moments as a cycle of struggle, a generation within the Palestine solidarity movement. We found ourselves struggling against a relatively new paradigm as the post–Second Intifada period, in which Israel would serially launch assaults on a besieged Gaza, was only just getting underway. In retrospect, I see us feeling around in the dark for the conceptual tools to understand its constitutive parts and their interrelation: the US, the Israeli state, the settler movement, Palestinian militancy, Palestinian civil society, the solidarity movement.

That paradigm has now been cracked open, its structure laid bare. Israel’s slow genocide of Palestinians has become a fast one, and the US’s rhetorical veneer of human rights, multilateralism, and international diplomacy—espoused so suavely with Barack Obama as the national figurehead—has slipped away, leaving Joe Biden’s retro 20th-century racism to set the taglines of American power. What remains is clear to see: a nuclear state, drunk on arrogance and backed to the hilt by the world’s hegemon, condemned its colonized underclass to permanent subjugation. But Gaza refused, and for its refusal, it is facing as much vengeance as the modern world can muster.

The extremely sensible—and, again, morally obvious—demand is for this vengeance to stop. Students recognize this, and its urgency. Because of its urgency, they will not be rebuffed. And because of their clarity, their voices have reached the subjugated themselves. Palestinians who rightly feel abandoned by the world can see themselves being seen and hear their own voices in the call of the students. This resonance is the voice of history itself, speaking now in what narrow opportunity human action and chance have conspired to provide for it.

Amid the horrors, this connection is extremely moving. I feel a release that has built up over the past dozen years—my entire adult life—that I have committed to this movement. A fever is breaking. But I also fear the window will close, and the resonances will desynchronize as a new paradigm sets in. My hope is that before then we hear everything that history has to say.

More from The Nation

What Luigi Mangione and Daniel Penny Are Telling Us About America What Luigi Mangione and Daniel Penny Are Telling Us About America

When social structures corrode, as they are doing now, they trigger desperate deeds like Mangione’s, and rightist vigilantes like Penny.

Donald Trump Is the Authentic American Berserk Donald Trump Is the Authentic American Berserk

Far from being an alien interloper, the incoming president draws from homegrown authoritarianism.

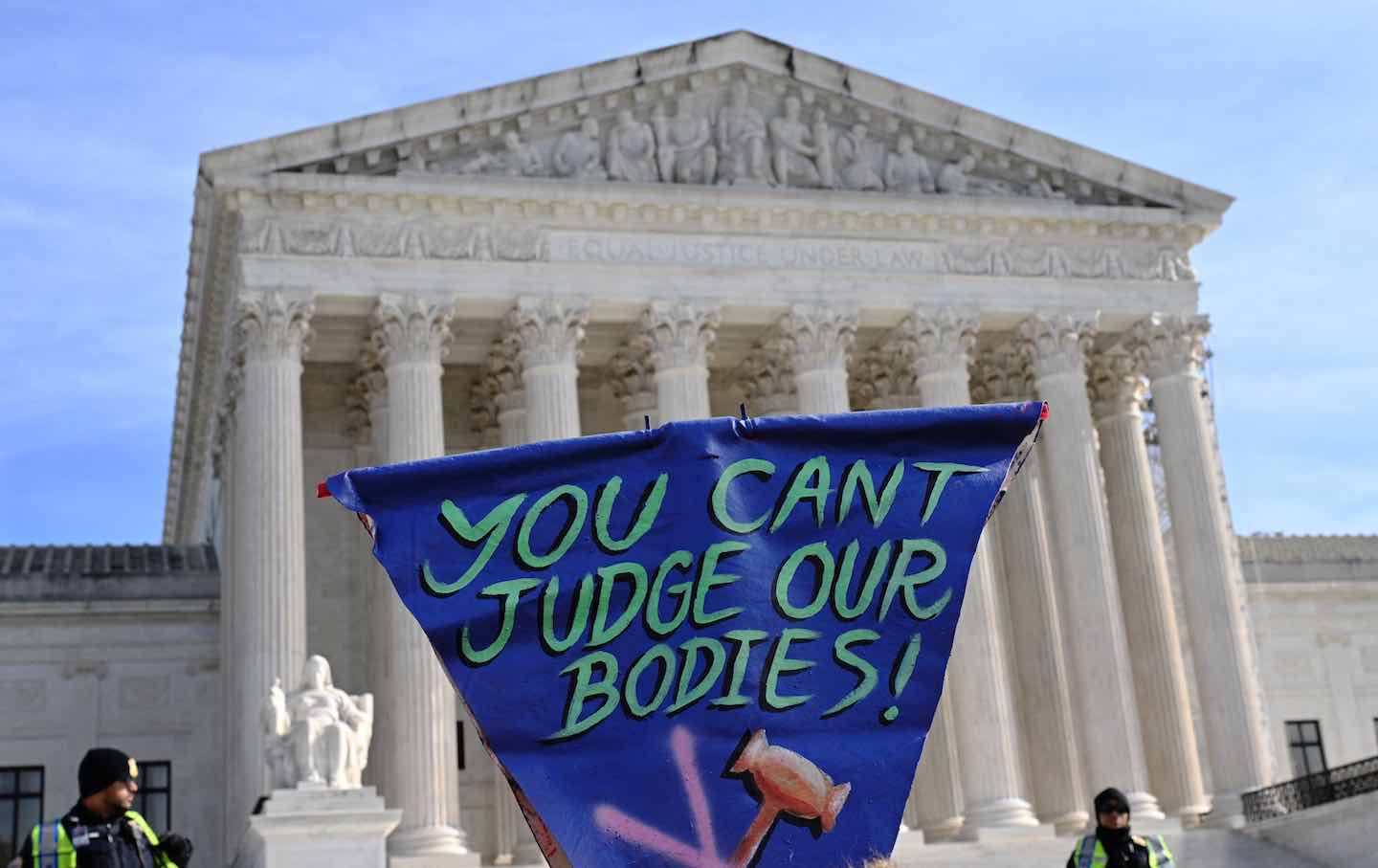

Banning Trans Health Care Puts Young People at Risk of Harm Banning Trans Health Care Puts Young People at Risk of Harm

Contrary to what conservative lawmakers argue, the Supreme Court will increase risks by upholding state bans on gender-affirming care.

If Democrats Want to Reconnect With the Working Class, They Need to Start Listening to Unions If Democrats Want to Reconnect With the Working Class, They Need to Start Listening to Unions

The Democrats blew it with non-union workers in the 2024 election. Unions have a plan to get the party on message.