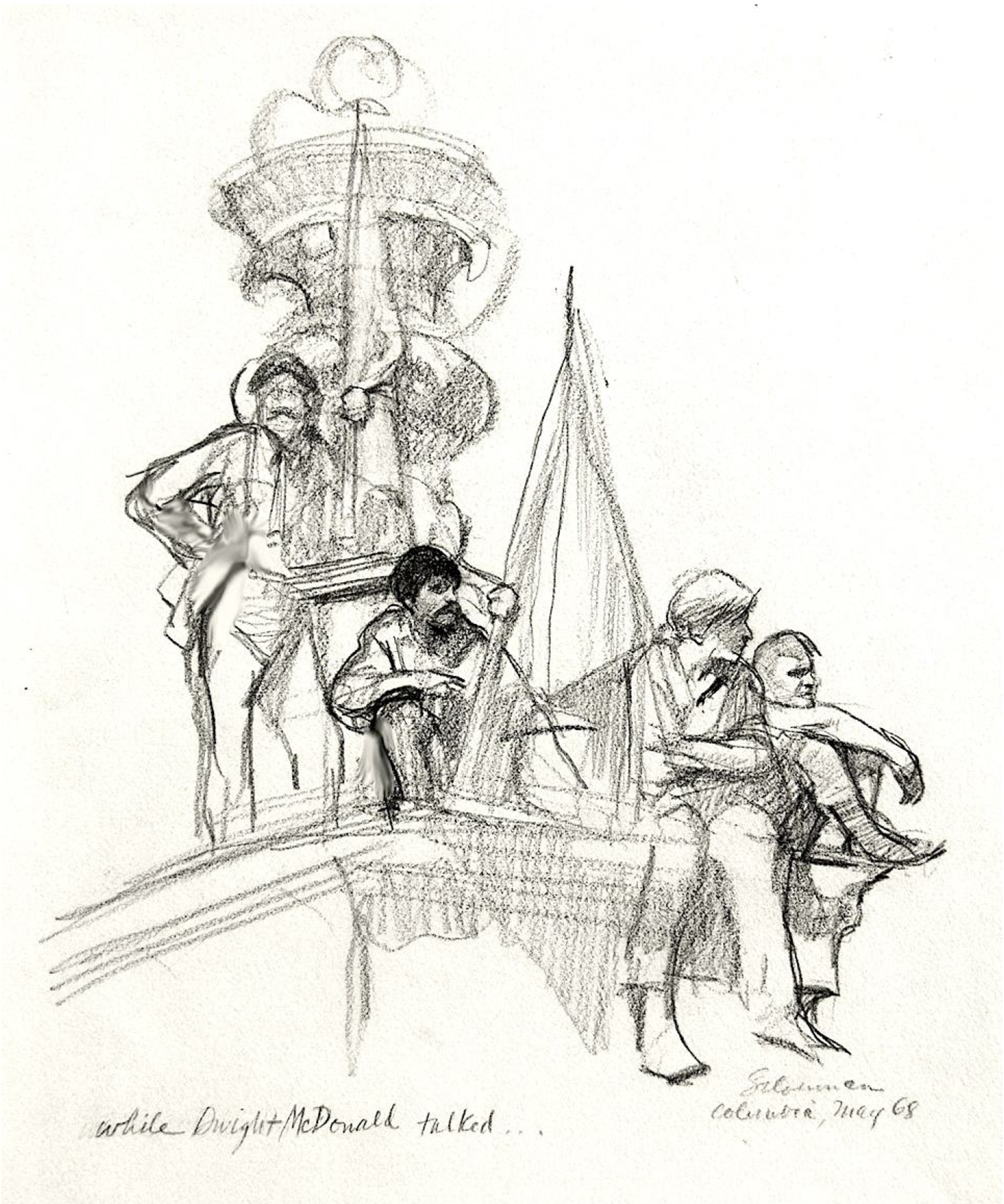

In late April 1968, New York magazine assigned me to cover the protests at Columbia University. After the NYPD, often violently, cleared Hamilton Hall and three other buildings, the demonstrations attracted national and international attention.

Hamilton Hall had been occupied by Black students who had been protesting the construction of a new gymnasium for months. The plans called for a separate entrance on the Harlem side of the street for athletes to enter. This act of segregation led the protesters to call the proposed separate-but-equal entrance “Gym Crow.”

Their takeover of Hamilton Hall was initially peaceful. The students were careful not to damage the physical property. At one point, they held a ceremonial nonviolent exit from the building. The three other buildings were occupied under the auspices of Students for a Democratic Society (SDS), a group that had spent the bulk of the decade actively engaged in Vietnam war protests.

The SDS-controlled buildings were where the bulk of the police violence took place. Martin Luther King Jr. had been assassinated just three weeks earlier, heightening the political tensions and leading to a much more charged atmosphere. The parallels to the continuing Gaza protests are inescapable, yet the protests were not identical. For example, in 1968 they didn’t have to face the complex challenges of advocating for the rights to free expression while avoiding antisemitism.

To the best of my memory, I completed all of the drawings in late May, 1968. The occupation of Hamilton Hall and the other buildings started on April 23.

—Burt Silverman

This view caught my eye as I stood near the Low Library, one of the many protest actions that took place over the three weeks following the occupation of the buildings. I called the drawing “Library Sculpture.” The demonstrators seemed fused with the giant sculpted marble flowerpot lights that sat on both sides of the classically columned Low Library. In my mind, it felt as if they had transformed into a kind of permanent sculptural symbol of protest.

What I also felt was the ominous and scary presence of the police. Mounted officers seemed like giant sentinels ready to pounce and dominate the large, open space in front of the library. Despite their passive posture, it felt oppressive. Violence, just by their mere presence, felt imminent.

There’s a dissonant quality in the cop’s dark black shirt and his crouched posture with his arm bent, which comes across as both casual or bored, even as he, too, is ready to strike.

The Columbia class of ’68 was determined to have a graduation ceremony. They marched through the quad with their caps and gowns in open defiance of the university. This student seemed to capture the essence of the protesters: whimsical, bare-chested, carrying a flag. I wish I’d had the time to capture the words written on the flag, but his overall pose and presentation said it all.

The SDS largely marginalized the female protesters, often reducing them to carrying out menial tasks or making coffee and getting food for their male counterparts. But they showed up for the celebratory march through the campus, jubilant, and defiant, and often carrying their infant kids with them.

I’m particularly fond of this drawing and the central young woman’s commanding pose

This police officer was staring daggers at me while I was drawing him. Of course, by eyeballing me, he failed to notice the student giving him a two-finger salute, a gesture that had become shorthand for those identifying with the protesters.

The nascent Puerto Rican independence movement also began during this time. I decided to capitalize on the increasing worldwide impact of the Columbia takeover. Unfortunately, I didn’t note the identity of the speaker.

This was a lithograph I made after finishing my assignment for New York Magazine, taken from two small sketches that I had scribbled on a notepad. Again, I wanted to stress the importance of women in the protests and reference the work of Käthe Kollwitz, the 19th-century German realist who I’ve long admired. Moreover, the dynamism and the drama of the lithograph does a better job of conveying how I felt at the time. I graduated from Columbia College in 1949 and keenly felt a sense of solidarity with the next generation of students, taking up arms against injustices both at home and abroad.