Cornell Championed “Free Expression.” Then It Rolled Out Protest Restrictions.

The university’s overhauled expressive activity policy has been criticized by both pro-Palestine advocates and student and faculty governing bodies.

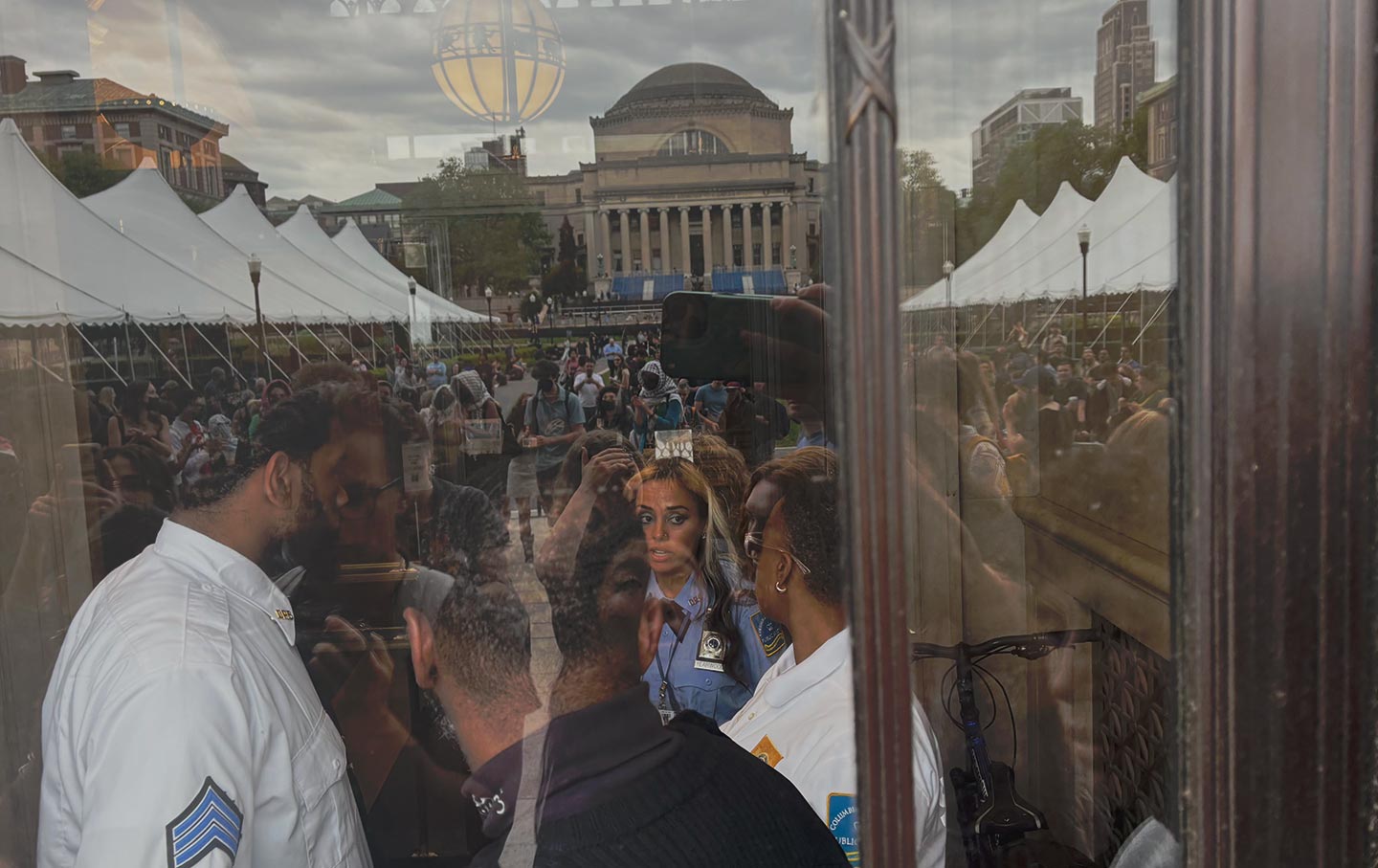

Pro-Palestinian demonstrators gather and take to the streets.

(Selcuk Acar / Getty)

In April 2023, Cornell University announced that the next academic year would feature the theme of “free expression,” calling on students, faculty, and staff to “develop the fluency and skills necessary for democratic participation, such as active listening, leading controversial discussions, leading effective advocacy and managing responses to controversial interactions.”

“It is critical to our mission as a university to think deeply about freedom of expression and the challenges that result from assaults on it,” said then-president Martha Pollack.

Now, over a year later, the university has overhauled its expressive activity policy and imposed multiple restrictions on campus protests.

The new policy prohibits the use of megaphones without prior approval—except from two locations on campus between noon and 1 pm. Disruption of university activities is prohibited. Posters and chalking is also limited, giving the university the authority to remove any content that does not meet its regulations. It is also recommended, but not required, to register protests involving over 50 people, prior to any demonstrations.

Following multiple high-profile suspensions, some students argue that the new policies further penalize pro-Palestinian speech on campus. “[Protesters] have to cover their faces, because if they don’t, they end up being suspended,” said Atakan Deviren, a sophomore and cochair of Cornell’s chapter of Young Democratic Socialists of America. “By talking to you right now, I am putting myself in danger.”

Cornell’s free expression policy was brought into the national spotlight when pro-Palestinian protesters disrupted an on-campus career fair on September 18, banging drums, pots, and pans in front of representatives for the defense manufacturer Boeing to protest Israel’s war on Gaza. Cornell administrators later announced that Momodou Taal, an international PhD student, was suspended for his involvement, though he was later reinstated with restrictions.

New university president Michael Kotlikoff said in a statement to students that the disruption was “a deliberate means of violating the rights of others who were participating in a scheduled university event.” Cornell’s interim expressive activity policy, which was instituted in January, prohibits protests that interfere with university operations.

Pro-Palestine protesters argue that the university is ignoring the will of the student body, citing a student assembly referendum calling for a ceasefire in Gaza and divestment from weapons manufacturers. “Listen to the people you’re here to represent and you’re here to take care of, because they told you what they want. And now the administration is making an active choice to not listen,” said Deviren.

The new expressive activity policy—said to serve as temporary guidelines until the university crafts a long-term policy with feedback from relevant stakeholders—has been criticized by pro-Palestinian advocates and Cornell’s student and faculty governing bodies. Despite multiple resolutions condemning it, a committee of 19 members will finalize a revised permanent policy.

“In a time when we see current policies and actions happening around the country, in academic institutions, [there are] really chilling policies [and] chilling actions,” said Denise Ramzy, lecturer at the Dyson School of Applied Economics at a faculty senate meeting. “The bravery it takes in 2024, sadly, to protest is immense. And so to add all of these restrictions on top of what students are doing [in particular] but the faculty as well, when all of us are afraid to speak out, I think [it] is dangerous and scary.”

“I think what the administration is forgetting is that in the code of conduct, it says that students have the right to voice their opinions, no matter how offensive or how rare they are,” said Maria Lima Valdez, a Native American senior from Mexico. Lima Valdez was condemned by Cornell’s administration in January after she published an Instagram post that read “Zionists must die,” which she maintains was not a threat. Lima Valdez was not formally penalized by Cornell.

During a virtual town hall with Jewish families on September 30, university spokesman Joel Malina told parents that Cornell is committed to fostering an environment where multiple viewpoints can be heard, stating that “if there were a faculty member that invited a Ku Klux Klan representative to speak or a student group that invited a KKK representative to speak, yes, we would allow that.”

But for many students, Cornell’s policies can seem arbitrary and discriminatory. Malak Abuhashim, a Palestinian masters student whose grandfather was born at a refugee camp after her family was displaced during the Nakba, says that the line between peaceful and violent speech is determined by whether or not the speech aligns with administrators’ views. “If you are saying things that are violent or hateful, but you are not opposing the administration or the university, they’re okay with that,” Abuhashim said. “As soon as you say something that could be perceived as hateful or violent, and you are opposing the university, or you are calling for them to change something, then they’re going to shut you down.”

Others feel that the university is within its right to protect its students. Erza Galperin, a pro-Israel sophomore who manages Cornell’s Jewish residence hall, said that recent disruptive protests intimidated students with differing points of view, alienating them rather than starting a discussion. “I think that possibility of dialogue is undermined when you have students threatening, intimidating, and screaming in the faces of their peers,” Galperin said. “I understand the disagreements. I don’t hold them personally, but there are ways for us to have these conversations.”

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →However, he said the university should still allow speech on campus, regardless of whether it becomes offensive—as long as it is not violently targeting students. “We don’t have to censor speech just because it might be offensive to someone, including me,” Galperin said. “I’ve seen speech that is offensive to me, and I’m not here to say we should censor it.”