What Do Elite Universities Owe Their Students?

As the Ivies push graduates into careers in consulting, finance, and tech, organizers with the Class Action movement are questioning their schools’ corporate partnerships.

A statue of Nathan Hale In front of Connecticut Hall on Yale University campus.

(Arnold Gold / Getty)

What percentage of Harvard College acceptances come from low-income families? A dinner bet around this question by professor Evan Mandery at the John Jay College of Criminal Justice quickly led to a larger discussion over what kinds of actors elite institutions were, whom they served, and how complicit they may be in weakening social mobility. In 2022, Mandery published Poison Ivy, a book that addressed the growing wealth disparity in America’s elite academic institutions, and he cofounded Class Action the next year. The organization asks students, academics, and everyone in between to think about what elite universities owe students and their communities.

Of course, Mandery isn’t alone in asking these questions. In 2015, Daniel Davis, Nick Bloom, and Amy Binder—a member of Class Action’s board of directors—studied the postgraduate job outcomes for graduates of Harvard and Stanford University, exposing a pattern of “career funneling.” Despite a diversity of majors and initial career aspirations, graduates from elite institutions disproportionately accepted offers in consulting, finance, and technology.

At Princeton, between 2016 and 2024, for example, the school’s career center reported that the largest industry of first destinations for graduates was finance, followed by technology and consulting. At Harvard, around 64 percent of the graduating class of 2024 choose careers in those fields.

This pattern tends to surprise many students who don’t envision themselves as tech bros. “I didn’t really even know that there was such a strong pipeline to finance and consulting. I think that’s the case for a lot of the students there,” said Zane Kiry, a first-generation graduate of Amherst College in 2024 and a student at the Princeton Theological Seminary. “You’ll encounter a small few who come in and are set to work in finance,” Kiry said, but they’re not at all the norm.

In 2026, graduates will likely be entering the worst college job market in years, and, for many, these careers might feel like the safest route to financial stability.

Stanford, which sits at the heart of Silicon Valley, serves as a major recruiting hub for the companies just down the road. Mandery explains how these universities share job contacts and hold fairs for these kinds of jobs, allowing companies to establish corporate partnerships early on. “When Goldman comes to town, there’s going to be a reception at the Charles Hotel,” said Mandery. “And that’s just not the case if you’re interested in doing the New York Urban Teaching Fellows.”

This trend didn’t form by accident, nor is it the case that elite universities are only letting in students who are already interested in these fields: There is a larger pipeline pushing unsuspecting students into these careers as soon as they step foot on campus. “Working in concert with universities, employers in banking, consulting, and big-tech sell students on a pathway to an elite lifestyle,” says Class Action, “selling their students to the highest bidder.”

This pattern led Kiry, as well as Emily Hettinger, a senior at Yale University, and Turner Van Slyke, a sophomore at Stanford University, to start organizing with Class Action. In November, these students gathered at Yale to “reimagine the academic-social contract” during the organization’s second annual conference, with the theme of “Reimagining Elite Higher Education,” following the inaugural conference at Brown University last year.

Class Action proposes a new “social contract”—an exchange between elite institutions and the communities they serve—”that rebuilds public trust by embracing inclusion over exclusivity, public service over private gain, and opportunity over inherited advantage.” As the public awards tax breaks, prestige, and federal funding, these schools should be responsible for creating leaders, promoting innovation, and serving the public good in return. While the Trump administration’s war on higher education is certainly denting—and, perhaps, irrevocably breaking—this historic contract, these universities still retain enormous power over creating the status markers and educational aspirations of the people who attend them.

Through Class Action, however, students are organizing so that these schools can do much more than produce management consultants. Their priorities include ending career funneling and “legacy” applicants, as well as creating a more equitable admissions system as a whole. “America’s trust in these institutions has plummeted,” writes Class Action. “Now, the outside actors are exploiting public mistrust for political ends, jeopardizing academic freedom and the capacity for universities to promote critical inquiry and open intellectual exchange.”

As one of the first people from her high school to attend Yale, Hettinger described coming to the university from a public school background as an “incredibly disorienting experience.” Students that enter these universities for a promise of a premium education find that it is muddied with elitism instead. “I quickly realized that something was missing between Yale’s reported ‘mission’ of spreading good and creating leadership in the world, and the actual outcomes of students.”

Students like Van Slyke who came to Stanford hoping to make a difference in their communities often find that careers in public service are pushed under the rug in favor of those represented by the leagues of big-name corporations on campus. Hettinger explained how she had just skimmed Yale’s career portal, where students could go to find resources for internships and jobs. Almost all of the articles spoke about tech, finance, and consulting. “There’s not a single article about how you can get involved in a public service career.” Instead, these students are driven to pre-business associations, consulting clubs, finance and tech clubs, that provide the “status that comes with admission…and the promise of the huge profits for people who work in these sectors,” said Van Slyke.

For freshmen entering college who come from backgrounds of diverse extracurricular and creative project backgrounds, these pipelines limit what success looks like and what markers prove a student is successful at these campuses. “A lot of people seek to validate their position and the institution of higher education by rushing into whichever student groups or organizations hold the most clout and are the most renowned on campus,” said Van Slyke.

While it might be easy to assume that students from lower-opportunity backgrounds now have the chance to find wealth-mobility pathways through these institutions, that is not always the case. Mandery explains that “when investment banks and management consultancies are recruiting, what they’re really looking for is drinking buddies and playmates.” In fact, the kinds of students who are getting recruited and receiving offers are disproportionately from wealthy families.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →After the November conference, the next step for attendees is to take what they’ve learned back to campus. Though the movement has brought together students from across the country, the goals are much more local. “The reason why people are so frustrated with these universities,” according to Hettinger, “is that they’re not serving the cities in which they reside, they’re not paying taxes, and they’re not supporting these local ecosystems.”

More from The Nation

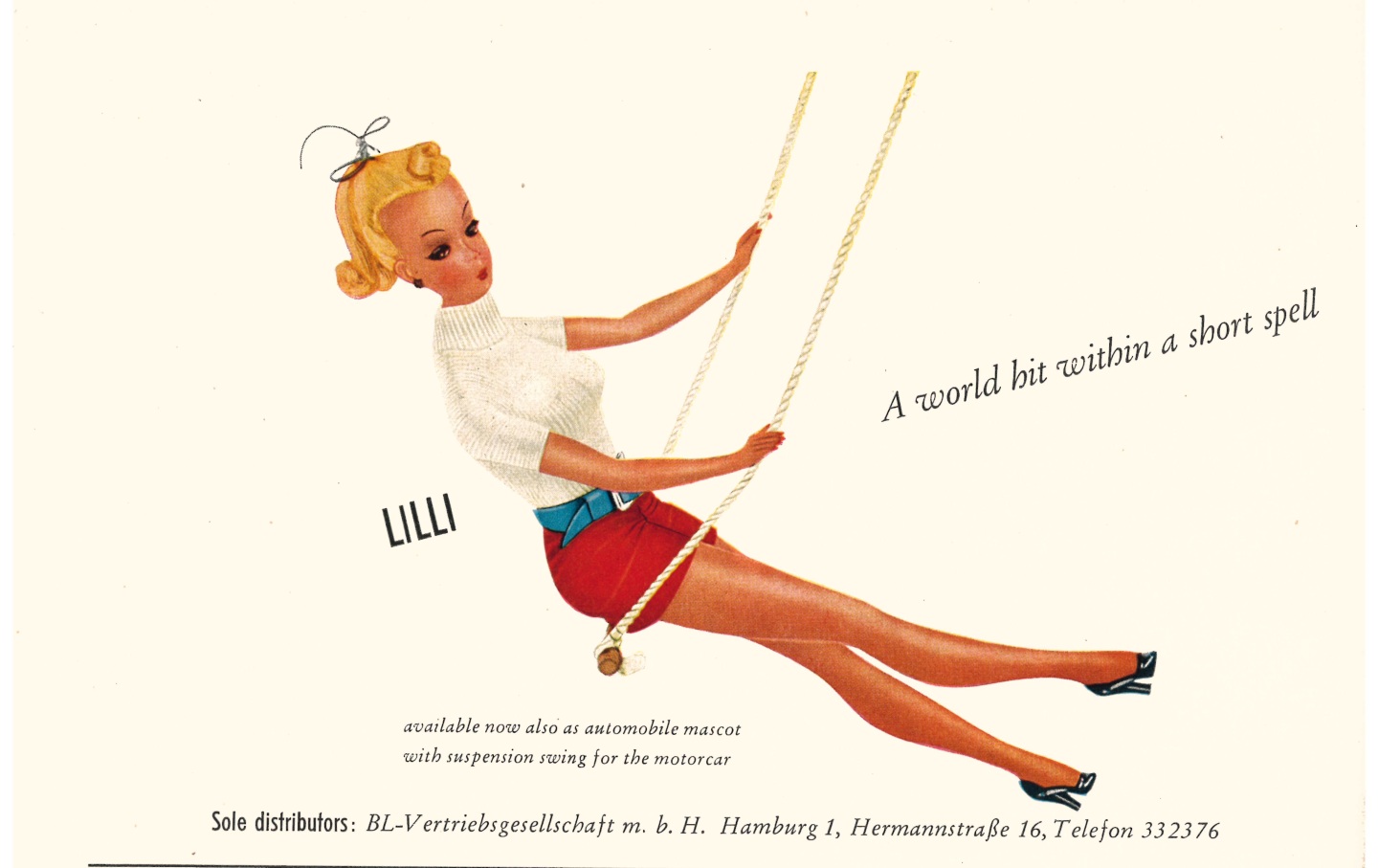

My Search for Barbie’s Aryan Predecessor My Search for Barbie’s Aryan Predecessor

The original doll was not made by Mattel but by a business that perfected its practice making plaster casts of Hitler.

FIFA Kisses Up to Trump With a “Peace Prize” FIFA Kisses Up to Trump With a “Peace Prize”

With the world’s soccer fans watching, Gianni Infantino, the great toady to the globe’s oligarchs, handed a made-up award to the increasingly violent US president.

A New Roosevelt Institute Report Confronts the Roots of Our Media Crisis—and Calls for Breaking Up Corporate Media A New Roosevelt Institute Report Confronts the Roots of Our Media Crisis—and Calls for Breaking Up Corporate Media

Today’s journalism crisis wasn’t inevitable, but it’s time to free journalism from the straitjacket of turning a democratic obligation into a profit-maximizing business model.

As Universities Fold to Trump, This Union Is Still Fighting for International Students As Universities Fold to Trump, This Union Is Still Fighting for International Students

While the University of California has often followed Trump's demands, union organizers have made protecting immigrants a top priority during contract negotiations.

Why Palestine Matters So Much to Queer People Why Palestine Matters So Much to Queer People

Palestinian identity can “upend the whole world order, if done right, if spun right, if we activate it enough. And I think queerness is a very similar kind of identity.”

The Tunnel Home: A Story of Housing First The Tunnel Home: A Story of Housing First

In the 1990s, a group of New Yorkers helped prove the effectiveness of a bold but simple approach to homelessness. Now Trump wants to end it.