The Endless Game

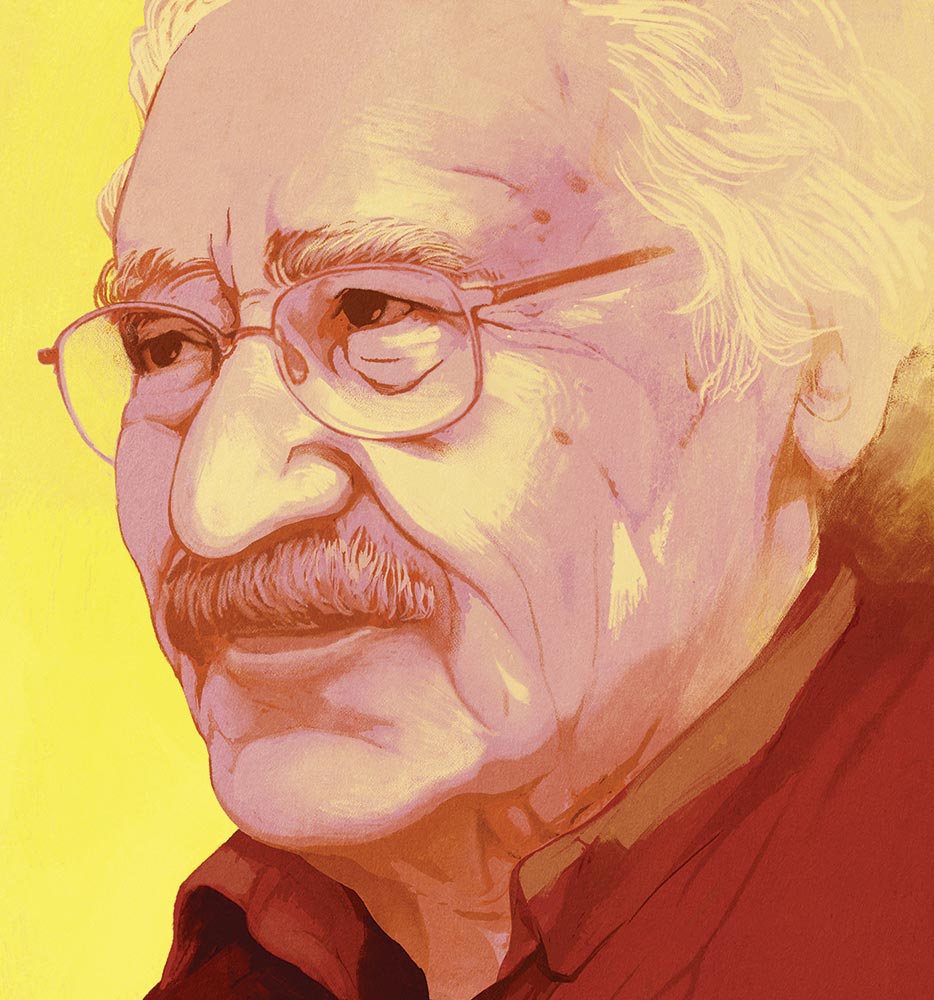

Gabriel García Márquez’s last work of fiction.

Gabriel García Márquez’s Last Lesson

His final novel, Until August, serves as not only a record of his last struggles with illness but also as a document of courage.

Toward the end of his life, as his blindness progressed, the shy librarian who answered to the name Jorge Luis Borges began to feel alienated from his alter ego, the celebrated writer. “I know of Borges from the mail,” he wrote in a prose poem published in 1960. “I live, let myself go on living, so that Borges may contrive his literature.”

Books in review

Until August: A Novel

Buy this bookI’ve found myself thinking of Borges ever since I learned about the posthumous publication of Until August, by Gabriel García Márquez, who died in 2014. The themes of García Márquez’s new novel will be familiar to readers of his Love in the Time of Cholera: Every August, Ana Magdalena Bach, a married woman on the far side of middle age, travels to an island off the coast of an unnamed Latin American nation to lay flowers on the grave of her mother. Her pilgrimage, however, is also motivated by a less dutiful reason: to get away from her husband long enough to take on a new lover.

Though Until August, like everything García Márquez wrote, is dense with detail and social observation, it isn’t his best work by any stretch. I suspect that if we removed the author’s name from the cover, a scholar might conclude it was the work of an inferior imitator. Garcia Márquez apparently felt the same way: Before his death, at age 87, he told his family in no uncertain terms that the book “doesn’t work and ought to be destroyed.” Nevertheless, his children and estate decided to disregard his wishes. Like Borges in his later years, they seem to have concluded that literature doesn’t belong to its author “but rather to the language and to tradition.” And despite the novel’s weaknesses, they should be praised for having done so.

If García Márquez’s main themes throughout his long and prolific career were the power of love and the love of power, his signature formal device was found in a technique of repetition: Events recur, names reappear, plots bend into circles, endings become beginnings. This cyclical notion of time, inherited from Borges, had metaphysical and political implications. Just as the course of our individual lives inevitably leads us back to our origins, the history of Latin America is not a tale of progress but an epic of stagnation in which hope clashes with fatalism. For García Márquez, repetition was first of all a narrative method—and perhaps a theory of literature.

Nowhere is this clearer than in a famous passage from One Hundred Years of Solitude. After the “plague of insomnia” strikes Macondo, the town’s inhabitants begin to come up with increasingly mind-numbing pastimes, hoping that boredom will eventually lull them to sleep. The last of these unamusing amusements is “an endless game” where a character identified only as “the narrator”—an obvious figuration of the literary writer—asks the others if “they wanted him to tell them the story about the capon.” When they answer “yes,” the narrator responds that “he had not asked them to say yes, but whether they wanted him to tell them the story about the capon”—which leads to an infinite loop.

Such cyclical repetitions also sit at the center of García Márquez’s posthumous novel. Until August is not so much episodic as iterative. Though Ana Magdalena gets involved with a different man each time she returns to the island, the novel has exactly one plot point: The particulars change, but the actions remain the same. This is not to say that the book lacks a narrative arc. The protagonist changes dramatically over the course of the novel; with every successive erotic encounter, Ana Magdalena—and, by extension, the reader—discovers new facets of herself. The men are all mirrors, but each one has quirks and idiosyncrasies that reflect different aspects of the protagonist. Time bends in a circle, but every turn of the wheel has unique elements.

The first of Ana Magdalena’s lovers, for example, is a “Hispanic gringo” whom she notices staring at her at the hotel bar, where the pianist plays incongruous bolero arrangements of Debussy. The gringo is dressed in white linen and sits alone at a table with a bottle of brandy and a half-empty glass. Ana Magdalena, too, has been drinking; to her bewilderment, she catches herself holding the man’s gaze. She was still a virgin when she dropped out of the faculty of arts and letters to get married, and she has never slept with anyone other than her husband. Little by little, though, she leads herself astray. The sex is transformative, inaugural, almost like a second first time. But this experience of liberation turns bitter the following morning, when she wakes to find the man gone. And not only that—he has also left money on the bedside table. Ana Magdalena feels the implication like a slap in the face: The man thought she was working that night.

And yet, despite the insult, the encounter with the businessman elicits a profound change in Ana Magdalena. Her husband, a teacher of music at the local conservatory, is a good man and a good partner; decades after their honeymoon, they still have fun in bed. But now, for the first time in her life, she realizes that her desires exceed the strictures of the role she has played since she was young. When she returns to the island the following August, she sets out to find another man to take to bed. This one is younger, with sleek and affected manners. He asks her to dance and grasps her waist and pulls her close without permission, until there’s nothing between them save their clothes. The sex is rougher, forceful, almost violent—and yet pleasurable.

The novel repeats these sexual encounters over and over again. Yet each night of passion leads to new discoveries: In the mirror of these men, Ana Magdalena begins to learn more about herself and even about humanity in general. But the repetitions also lead her to darker insights that echo the one elicited by the money her first lover left on the bedside table. At one point, years after the affair with the sleek young man, she recognizes her lover’s face in a police composite sketch: He’s wanted for the murder of two widows.

But even while Until August’s iterative structure is effective, and its feminist gestures—how else to call them?—are at once surprising and welcome, the fact remains that, as Michael Greenberg noted in The New York Times, García Márquez’s final work sometimes reads less like high literature than like a Harlequin romance. The prose is often hackneyed, and clichés abound: The omniscient narrator describes more than one lover as “exquisite.” The philosophical depth of One Hundred Years of Solitude—so often overlooked by Anglophone readers who mistook García Márquez’s novel of ideas for entertaining tropicalia—is almost entirely absent from Until August.

Worst of all, the most visible repetitions in this last novel don’t seem to be deliberate choices. They are not metaphysical gestures, or political statements, or avant-garde narratological tricks, but evidence of a diminished vocabulary and a fading memory. It’s not just that the same tired adjectives appear over and over again: The novel often reiterates points established just pages earlier, as if the text itself were straining to remember what it was trying to say.

These undeniable flaws perhaps explain why some critics have called the decision to publish Until August a cynical bid for profit—although the new novel is unlikely to have a significant effect on a literary estate with tens of millions of sales to its credit—while others have expressed fears that it might damage the great author’s reputation. “I worry that something has been authorized that shouldn’t have been authorized,” declared Salman Rushdie. “Everyone will read it because of the name of the author, but it may not do him justice.”

But the most serious charge is that publishing Until August is, at best, an invasion of the author’s privacy and, at worst, a form of elder abuse. When I met García Márquez in 2006—I was 16 at the time—he was still lucid enough to crack jokes. He even did me the honor of reading a few of my short stories; the advice he offered—that I should stop imitating Borges and instead write about my own life—has guided me ever since. Later that day, García Márquez showed me the proofs for the 40th-anniversary edition of One Hundred Years of Solitude. “I had forgotten most of it,” he muttered. “I’m surprised to discover it’s good.” I naïvely took the statement for a joke, but a few years later I realized it likely wasn’t. I became aware of an open secret that, despite his efforts to keep it quiet, had long circulated among his friends: The great writer had dementia.

Still, even as his mind declined, García Marquez kept trying to finish Until August. He produced no fewer than five drafts of the novel and at one point seems to have been satisfied with the final version, though he later concluded that he had lost too much of his memory to complete the project and asked his family to destroy it. Cristóbal Pera, the editor of García Marquez’s memoirs, whom the estate tasked with reconciling the handwritten corrections on the various Until August manuscripts, was wise to preserve the traces of the writer’s struggle with his illness. Instead of artificially enriching the book’s vocabulary or deleting its involuntary repetitions—alterations that would have perhaps made it “better” in a banal sense—Pera presents us with García Marquez’s last, heroic attempt at finishing a novel.

Here, I think, lies the answer to the charge that the novel shouldn’t have been published: Until August may be a record of the debilitating effects of dementia, but it’s also a document of courage. The writer Wendy Mitchell, who has been open about her own experiences with the disease, put it best in an opinion column for The Guardian: García Márquez’s children, she wrote, “should be proud that their father continued writing despite his condition.” The same, I would argue, is true of his readers. Instead of measuring this novel against the masterpieces of a writer in his prime, they should approach it as the titanic final effort of a man who, confronted with the end of language and memory, tried to follow Dylan Thomas’s advice not to “go gentle.”

This exercise in generous reading strikes me as especially important for my generation of Latin American writers. Many now view García Márquez’s brand of magical realism, with its small towns, biblical deluges, and underage sex workers, as little more than tired exoticism. For a long time now, our totemic author has been not the Colombian master but Roberto Bolaño, a writer whose style and concerns are the opposite of those of the so-called Boom latinoamericano. To many younger readers, the central question elicited by the publication of Until August is not the ethical dilemma of whether it should have been released, but rather the most devastating sentence in literary criticism: Who cares?

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →Well, I do, of course, along with many others. And so I’d like to present what is, to my mind, the best defense of Until August: The novel is García Márquez’s eulogy for his own literary generation. Over the course of its pages, the island where Ana Magdalena Bach tends to her mother’s grave suffers the accelerated change that economists euphemistically refer to as “development”: The canoes are replaced by ferries, the hammocks by king-size beds, the ramshackle hostel by a gleaming hotel. García Márquez appears to be acknowledging that the time has come to bury magical realism and, to quote Borges yet again, “imagine other things.”

I find it moving that the protagonist of Until August, unlike the female characters of García Márquez’s masterpieces, is a woman endowed with an inner life rather than an allegorical figure. I like to think that after Memories of My Melancholy Whores, the last book he published in life, was released to mixed reviews in 2004, he decided that he didn’t want a story about a 90-year old man who falls in love with a teenager to be his final novel. Instead, he set out to write about a grown woman who discovers that she’s free to live as she chooses. That he named his first and last female protagonist after the wife of a celebrated artist suggests that Ana Magdalena Bach is a cipher for the great love of his life, Mercedes Barcha. Tend to my grave, he seems to be telling his soon-to-be widow, but make sure to take other lovers.

I choose to believe that García Márquez, like Borges before him, came to understand in old age that he had ceased to be a man and had instead become an author. This realization was the opposite of megalomania: He knew that his work exceeded the boundaries of his ego and would long outlast his person. That his conviction on this point wavered at the end is only natural: Don Quixote, too, gave up on literature on his deathbed. Still, I’m glad that García Márquez’s children chose to honor the version of their father who still retained enough strength to affirm that, when it comes to art, death is powerless.

More from The Nation

What Comes After the Apocalypse? A Q&A With Joshua Oppenheimer What Comes After the Apocalypse? A Q&A With Joshua Oppenheimer

Oppenheimer’s latest film, The End, is a Golden Age, postapocalyptic musical crying out from the depths of the earth.

The Peculiar Case of Ignatius Donnelly The Peculiar Case of Ignatius Donnelly

The Minnesota politician presents a riddle for historians. He was a beloved populist but also a crackpot conspiracist. Were his politics tainted by his strange beliefs?

The Agony of Aaron Rodgers The Agony of Aaron Rodgers

Is he the world’s most interesting athlete or is he just a washed-up crackpot?

Can You Understand Ireland Through One Family’s Terrible Secret? Can You Understand Ireland Through One Family’s Terrible Secret?

In Missing Persons, Clair Wills's intimate story of institutionalized Irish women and children, shows how a family's history and a nation’s history run in parallel.

Peter Schjeldahl’s Pleasure Principle Peter Schjeldahl’s Pleasure Principle

His art criticism fixated on the narcissism of the entire enterprise. But over six decades, his work proved that a critic could be an artist too.

How the Western Literary Canon Made the World Worse How the Western Literary Canon Made the World Worse

A talk with Dionne Brand about her recent book, Salvage, which looks at how the classic texts of Anglo-American fiction helped abet the crimes of capitalism, colonialism, and more...