Esperanza Spalding and Milton Nascimento’s Endless Reinventions

In a collaborative work, the two artists find a fusion of old and new that charts a path forward for jazz and pop’s future.

Tony Bennett and Lady Gaga, Joni Mitchell and Brandi Carlile, Loretta Lynn and Jack White—a well-publicized school of winter/spring musical partnerships has emerged over the first decades of this century, with young (or youngish) musicians and their celebrated elders bridging sizable distances of age and style to collaborate productively. The process brought rejuvenating energy and renewed attention to the aging (or aged) veterans in the duos, while conferring the grace of respectful deference upon the acolytes. It’s tempting to interpret the motivations on both sides of these team-ups cynically, but why be ungenerous? The old lions got one more chance to work up a roar, and the young stars got to show some humility, something rare and precious in pop culture, even when it’s entwined with careerism.

A new album, Milton + Esperanza, presents yet another pair of cross-generational duet partners from divergent musical worlds: Milton Nascimento, the long-beloved Brazilian singer-songwriter, who’s now 81, and Esperanza Spalding, the lauded American jazz-pop singer-bassist-composer, who’s 39. The pairing is clearly of a piece with the teams of Tony and Gaga and the others, though it’s significantly different—a more complex creative collaboration between artists melding their sensibilities. They reach out to each other, and both stretch a bit to land on new ground. Nascimento sings music that Spalding composed after being inspired by Nascimento’s writing, while Spalding sings Nascimento’s compositions in Portuguese. And the two of them take part in experiments with samples to create aural soundscapes of music, ambient sounds, and spoken words.

Spalding is no copycat latching on to a trend—not here, not ever. She has long made it a point to honor the musicians who have mentored or influenced her. Twelve years ago, she wrote a song, “City of Roses,” about the nurturing musical environment she found as a gifted young musician in her native Portland, Oregon, for her album Radio Music Society. Spalding invited one of her early mentors, the trumpeter and educator Thara Memory, to co-arrange the piece, and together they won a Grammy. The same album featured a Hall of Fame roster of seasoned jazz greats, including the tenor saxophonist Joe Lovano and the drummers Billy Hart and Jack DeJohnette, along with younger artists such as Q-Tip and Lionel Loueke. Spalding had been working regularly and recording with Lovano, playing double bass in his bebop quartet, working like an apprentice to a master on the bandstand.

I saw Spalding playing with Lovano at the Village Vanguard during this period. After the show, I asked Lovano if he would introduce me to Spalding, so I could tell her how much I appreciated her work in the group. Lovano demurred firmly, saying that Spalding was keeping a low profile so she could “just be the bass player in the band” and “learn from that.”

A decade later, Spalding was back at the Vanguard in a different role, now singing—only singing, without a bass in sight—in a run of duo shows with the pianist and composer Fred Hersch, who was in his late 60s at the time. The performance I saw was so remarkable that I went back two nights later and ended up even more impressed, and moved, by the elastic symbiosis of this seemingly incongruous matchup. Singing a mix of jazz standards, vintage pop tunes, blues, R&B numbers, and originals, Spalding seemed to have the entirety of American musical history at her command. She honored the compositions but also tapped the jazz tradition of improvising in the moment to assert one’s individual identity—in improvised lyrics with contemporary bite and cadence, and in her inventive scatting. Just as strikingly, she inspired Hersch to play with a punch and wit I had rarely heard from him: They were not separated by age or generation in these performances but working as peers. (Spalding and Hersch recorded one of their shows in this series for an album released as Alive at the Village Vanguard, which was nominated for two Grammy Awards, including Best Jazz Vocal Album.)

“That’s how the music is,” Spalding said in a video interview for JazzTimes magazine. “You’re blessed enough to meet somebody that’s a master, and then little by little with that person and due diligence, the past keeps moving along if you learn how to apply it and have the opportunities to apply it.” While tropes of generational conflict virtually define popular music, casting the sensibility of young people’s songs as a rejection of the previous generation’s values and tastes, Spalding has always sought out the elders she admires for inspiration, providing fuel for her own movement forward.

It was through two other renowned jazz elders, Wayne Shorter and Herbie Hancock, that Spalding was first introduced to the music of Nascimento. Shorter had collaborated with Nascimento in 1975 on a touchstone union of jazz and Brazilian music, Native Dancer, a de facto dual-artist record released under Shorter’s name but with more than half of the tracks composed by Nascimento, who sings and plays guitar on his songs as well. Hancock was the keyboard player on the album. Through his introduction, Spalding connected with Shorter and soon grew close to him, eventually collaborating on a pair of genre-defiant, long-form works of music and text based on Greek mythology, Gaia and Iphigenia. (The latter was staged as an opera in late 2021, a few years before Shorter’s death in March 2023.) “Through Herbie and Wayne Shorter, I came to know about the blessing of this Earth which is Milton ‘Bituca’ Nascimento,” Spalding recalled in a Facebook post earlier this year. “I’m swimming in deepest graaaatitude for their profound lineage, carrying us all in the music.”

Nascimento and Spalding first came together for her 2010 album Chamber Music Society, on which he joined her in singing “Apple Blossom,” a lilting, sparkly ballad with a Brazilian feel composed by Spalding. He made a lasting impression on her, she would say, though they wouldn’t work together again until 2022, when Nascimento asked her to join him as a guest in a few of the concerts of his farewell tour. Between shows, Nascimento’s son invited Spalding to Brazil to produce an album for his father, and Milton + Esperanza was the result.

The project is not quite a Milton Nascimento album and not quite an Esperanza Spalding album either, though it’s much more his than hers through the force of Nascimento’s influence. “Ninety percent of things I write, I’m thinking of him,” Spalding has said. “I’m thinking of his voice. I’m imagining singing it with him. He’s a very present part of my creative imagination.”

About a third of the album’s 16 tracks are songs from Nascimento’s deep catalog, material he has recorded multiple times over the course of his six decades in music: “Cais,” “Outubro,” “Saudade dos Aviões da Panair,” “Um Vento Passou,” and the majestic “Morro Velho.” The arrangements are mostly spare and tasteful, with a small ensemble of acoustic instruments augmented by watercolor washes of strings and subtle synthesizers. What’s new and most revealing in the versions of the Nascimento favorites here is the sound of his singing. Once a limber, light baritone who could swoop into the tenor range or rumble in the low register, Nascimento sings now with a fragile voice, reedy and soft but powerfully expressive. When he sings, in “Cais,” of imagining hope—inventing a pier to launch his dreams into the sea—there’s a wistful quality of resignation in his voice, as if he’s holding on to dreams that he recognizes as merely dreams.

When Spalding joins Nascimento for duet performances, as she does on more than half of the songs, their voices work beautifully as forces in contrast: hers airy and fluid, his brittle and coarse—a soft egg and bacon, or ice cream sprinkled with cracked nuts. They mainly sing in unison rather than in harmony, with an intimate, unfussed-over ease. They sound like two friends sharing songs they both happen to know and like. You can picture them watching each other for cues to the next line in the lyrics. You can hear them smile as they sing.

On the four Spalding originals, she handles the lead vocals herself, adjusting well to the Brazilian conventions of singing conversationally on the bottom of the notes, almost but not quite flat, and pushing the beat a bit instead of hanging behind it as American jazz singers do. It’s unclear why Nascimento didn’t join her as a duet partner for all of her material, though he croons a companionable backup on Spalding’s “Get It by Now,” the funkiest of the album’s tracks. Spalding shows that she wants to play a supportive role, editing two of her pieces here down to less than a minute so they serve an interstitial function. The brief vamp that Spalding titled “Late September” leads into Nascimento’s melancholy evocation of October in Brazil, “Outubro.”

Over the years, Nascimento has made plain his special fondness for the music of the Beatles, recording an unexpectedly nuanced cover of “Hello, Goodbye” as a ballad and once composing an homage to the group, “Para Lennon e McCartney.” On Milton + Esperanza, the two singers do “A Day in the Life”—in unison again, with a gentleness so unaffected that they evoke a couple singing along to the radio. The performance comes across as nothing like professional performance and wholly like quotidian life, the theme of the song. It couldn’t be plainer or simpler, and it’s perfect.

Another duet, between Nascimento and guest artist Paul Simon, is exquisite, too. Nascimento wrote the song, “Um Vento Passou” (“The Wind Has Passed”), for Simon, with lyrical images of silence as a sound in the air. As Spalding does, Simon adapts to the Brazilian vocal tradition, singing delicately in Portuguese—again, low in the notes on the verge of going flat. The octogenarian singer-songwriters sound like two old friends sharing memories, sitting on a park bench like bookends; the warm, familial duet stands out on an album rich with them as a reminder of how good a singing partner Paul Simon can be.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →To close the album, Nascimento and Spalding chose “When You Dream,” a composition by the artist who brought them together: Wayne Shorter. It’s a sweet and eerie song about love and nature, life and death, and how they connect. The composer’s widow, Carolina Shorter, joins Nascimento and Spalding on the vocals. But the summing-up statement of the project comes right before this song, in a track of synthesizer soundscape music and spoken language titled “Outro Planeta.” Almost buried in the mix, Nascimento and Spalding talk quietly. Spalding says something in Portuguese and laughs. Nascimento pauses for a moment and says, “The music for me is basically friendship, love, children, ocean—the life.”

More from The Nation

What Comes After the Apocalypse? A Q&A With Joshua Oppenheimer What Comes After the Apocalypse? A Q&A With Joshua Oppenheimer

Oppenheimer’s latest film, The End, is a Golden Age, postapocalyptic musical crying out from the depths of the earth.

The Peculiar Case of Ignatius Donnelly The Peculiar Case of Ignatius Donnelly

The Minnesota politician presents a riddle for historians. He was a beloved populist but also a crackpot conspiracist. Were his politics tainted by his strange beliefs?

The Agony of Aaron Rodgers The Agony of Aaron Rodgers

Is he the world’s most interesting athlete or is he just a washed-up crackpot?

Can You Understand Ireland Through One Family’s Terrible Secret? Can You Understand Ireland Through One Family’s Terrible Secret?

In Missing Persons, Clair Wills's intimate story of institutionalized Irish women and children, shows how a family's history and a nation’s history run in parallel.

Peter Schjeldahl’s Pleasure Principle Peter Schjeldahl’s Pleasure Principle

His art criticism fixated on the narcissism of the entire enterprise. But over six decades, his work proved that a critic could be an artist too.

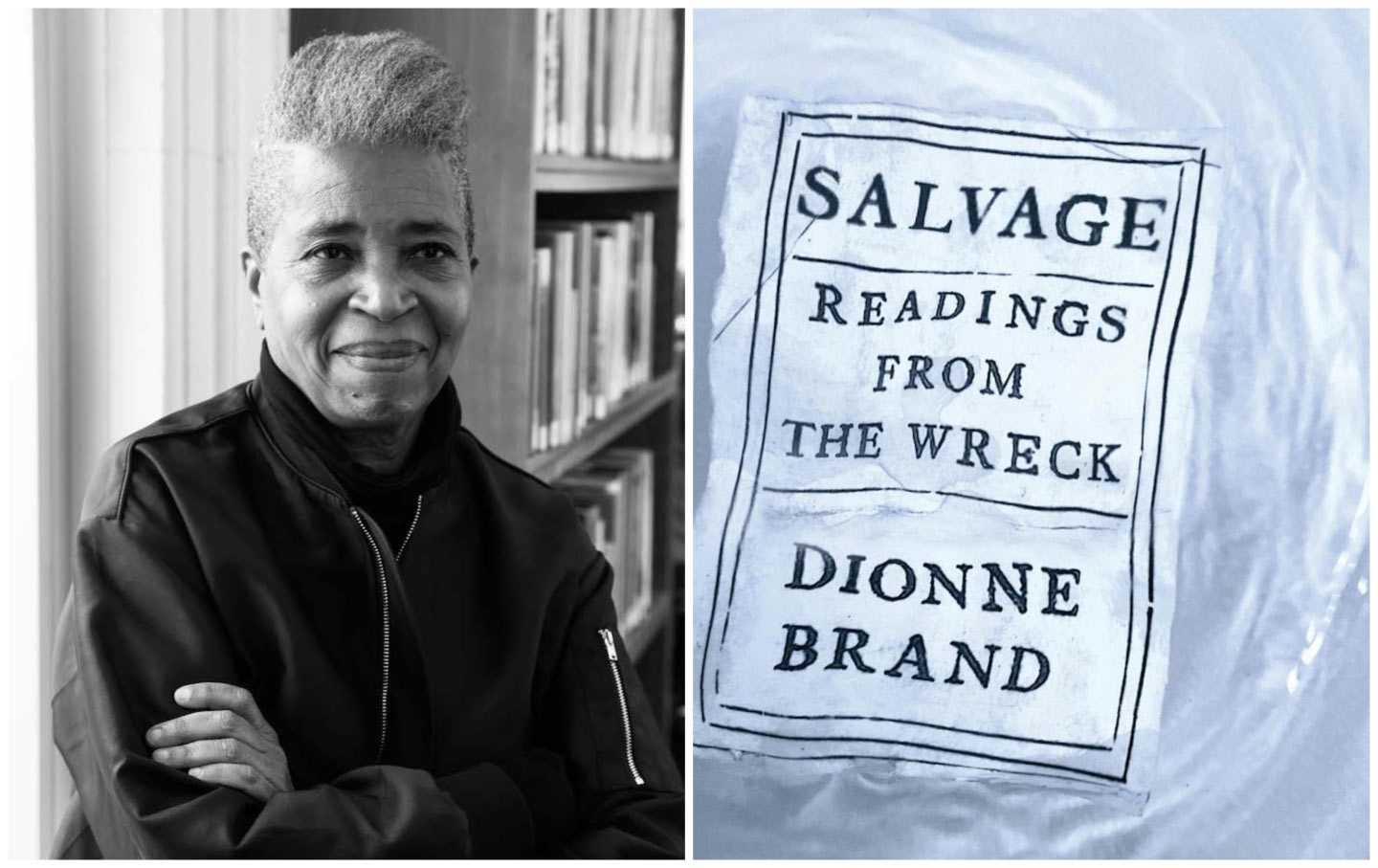

How the Western Literary Canon Made the World Worse How the Western Literary Canon Made the World Worse

A talk with Dionne Brand about her recent book, Salvage, which looks at how the classic texts of Anglo-American fiction helped abet the crimes of capitalism, colonialism, and more...