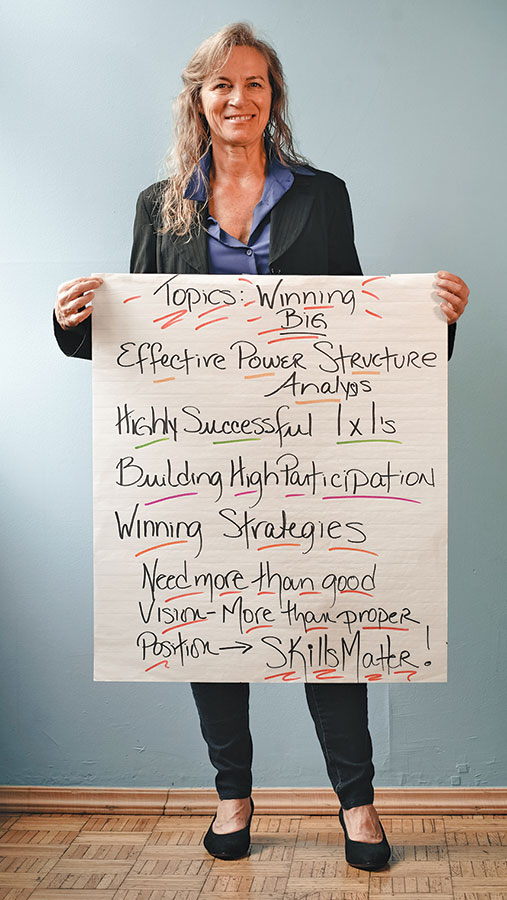

“You Blitz!” Jane McAlevey’s Answer to What to Do When We Don’t Have Enough Time.

The Nation’s strikes correspondent was happy to be profiled in The New Yorker. There was just one problem: She didn’t want any mention of her terminal illness.

Icontacted Jane McAlevey for a profile in The New Yorker in March 2023, just a few days before she celebrated the publication of her fourth book and her latest triumph over what would ultimately prove to be a fatal blood cancer. Jane was enthusiastic, even generous, about the prospect of a near-stranger probing her life in order to put facets of it on public display. “Between the Chicago mayor’s race and the UAW, UPS fight, there’s so much potential for good right now,” she wrote to me when I first raised the idea with her. “I think this new book, probably my last though I did have a plan for one more—on power—lands at a very good time.” Almost immediately, she offered me contact information for her family, friends, and colleagues and made herself available for “Zoom booms” (her phrase). Just one thing, she added, albeit not in so many words. I trust this piece won’t discuss my cancer diagnosis.

For at least a week, I tossed and turned. I did not want to violate Jane’s wishes, but I also understood her cancer diagnosis as a vital narrative thread in her life that could not simply be bracketed away. For days, I stared at the ceiling wondering how to proceed, until I finally grasped my dilemma. I had arrived at Step 4 in Jane’s “Six-Step Organizing Conversation” protocol—I needed to “frame the hard choice.” Would Jane rather see the article run while she was alive, and we could work together to address her diagnosis in a way that felt acceptable to her, or would she rather the piece run as an obit upon her passing? It was her choice. This kind of existential organizing conversation, I surmised, would best be conducted face-to-face. So, after persuading a somewhat skeptical editorial team that a second reporting trip was necessary, I returned to New York.

I arrived on a rainy April weekend, Jane’s only available window of time in an otherwise packed schedule. For me, the timing was ominous; it was Pascha—Greek Easter—the most important holiday in the Greek Church. (In an additional feat of existential organizing, I persuaded my Greek mother that spending the night of Christ’s Resurrection talking with Jane was its own kind of worship of life amid death—a point that my mother eventually conceded.) Before my visit, Jane sent me an agenda: from 3 to 5 pm, drinks with an organizer who was visiting from the UK; from 5 to 7, a chat, just her and me; dinner at 7; then all serious conversation needed to be wrapped up by tip-off. It was Game 1 of the NBA playoff series between the Warriors and the Kings. Jane, who’d lived in the Bay Area for decades, was a die-hard Golden State fan.

When I got to Jane’s rent-controlled high-rise apartment on New York City’s Upper West Side, she was wearing jeans and a Warriors jersey. The walls of her apartment were painted royal blue. “For the Warriors,” she said, grinning and gesturing to the sueded blue modular furniture, the yellow throw pillow, the jar of sunflowers perched on the coffee table. Jane introduced me to her guest, a research director at the University and College Union, a 120,000-member trade union representing British academic workers, whose leadership has been heavily influenced by Jane’s writings. She set out little bowls of mixed nuts and made gin and tonics while the organizer updated her on the preparations for an upcoming strike, as Jane nodded along, interrupting every so often to ask where the union had shored up support, what work remained. Jane’s questions were more than polite inquiries. She was asking about her core obsession: Ordinary people’s power, though relative, is real. Jane wanted to know how they were using it.

After her guest left, Jane and I moved to her kitchen. I sat at the table while Jane bustled around, thawing a jar of last summer’s homemade pesto for pasta. Despite her poor health prognosis, Jane was full of life, beaming with characteristic intensity. She was chopping carrots when I broached the subject of her impending death: “As I see it, Jane, your life has invited people to the battle for theirs.” I paused, considering my words. “What do you want them to know?” Jane didn’t so much as look up, the knife blade flashing fast across the cutting board. “Blitz,” she answered, as if by instinct. “You blitz.”

Jane McAlevey was born to a fighter pilot father and a dying mother in 1964. Her father, John McAlevey, flew aircraft during World War II with the Eighth, an air force squad that boasted a striking 98 percent success rate. As John would explain to his daughter years later, as a fighter pilot, simply detesting fascism wasn’t sufficient to defeat it. That goal required more: a flawless analysis of the target, an impeccable strategy that capitalized on the unit’s strengths while exploiting the opponents’ vulnerabilities, and immaculate tactical execution. Anything less meant that the fascists won and you died. “I think that the high-risk gene came a little bit from my old man,” McAlevey said on a panel last year. His dog tags jangled from her key chain.

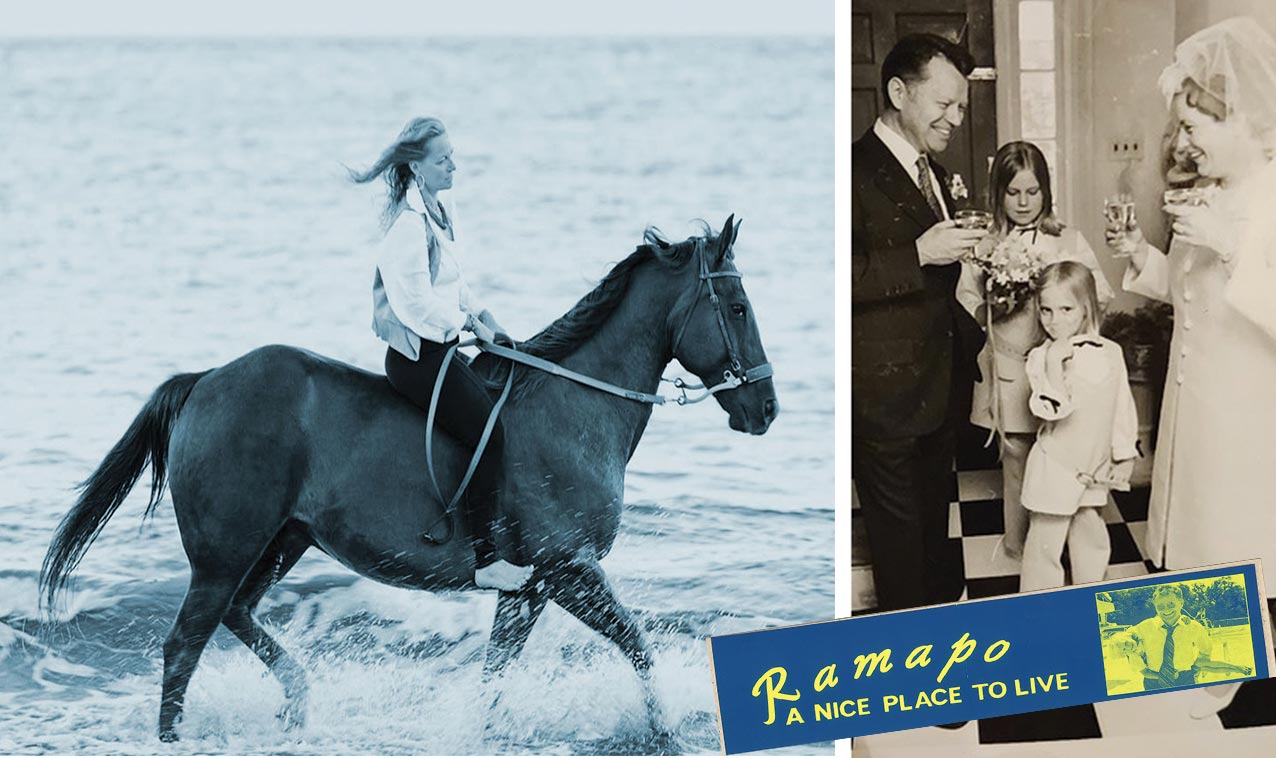

Her mother’s death opened the door to a new love for Jane: horses. Her newly widowed father was befuddled about how to care for his children, especially tiny Jane, and he bought the family a pony, a “consolation prize,” Jane told me, for a dead mother. The distraction worked. For Jane, horses became “the most reliable, stable, joyous” relationships in her life. She credits her connection with horses for enabling her to become a functioning adult despite her rocky upbringing. She spoke about her love of horses in short, elemental phrases: “Just pure good. Just pure joy. From 2 years old on. They were always a safe space. Always a haven.” As a kid, Jane worked in the stables and, as an adult, often favored organizing campaign jobs that allowed her to bring Jalapeño, her horse of 32 years—and Jane’s longest relationship outside of those with her siblings. A longtime colleague of hers told me that Jane had a photo of her and Jalapeño on display in all of her offices, the way a mother might carefully place a portrait of a child. Jalapeño died in November 2021, weeks after Jane was diagnosed with multiple myeloma. At times, during my conversations with Jane, I had the feeling I myself was handling a horse, a thrashing body with intelligent eyes and a kick that could break my shins. But the more still and grounded I was, the more she yielded to the path ahead. Horses had offered Jane both stability and liberation. “They played the role of replacing my mother,” she told me.

Meanwhile, Jane’s father poured himself into his burgeoning political career, first as mayor of Sloatsburg, New York, then as supervisor in nearby Ramapo, where he advocated for progressive urban development, envisioning public green space alongside public housing. “Our activist politician father was out to, you know, change the world,” Jane told me. “We would see the old man on Friday nights, pizza nights.” Although mostly absent in the raising of his children, John became an important political mentor for his daughter, often bringing her along on his campaign events and political meetings. Jane’s father had impressed her with two lessons: Fascism is coming, and ordinary people are a fundamental source of power. Once, while the family was driving in a rainstorm, Jane recalled, her father pulled the car over and marched the children to a muddy trench that construction workers were digging to lay utility lines. John instructed his children to thank the crew for working in the rain to build a drainage system for the city. “He wanted us to know that the men building the sewers were just as valuable as doctors,” Jane said. But John also impressed Jane with his conviction that, although everyone who labors in a society matters, it is only by following a strategic plan that working people’s power could be used to win greater resources and respect for their work. Organizers are key to developing and executing that strategy. “It’s like we’re soldiers,” Jane said. “Good organizers are the standing army that trains the volunteer army. And you can’t win without either.”

After her mother’s death, things at the McAlevey home were tough. The pack of seven siblings grew up just this side of feral. Jane spent most of her early years unsupervised and grubby, trailing her older siblings as they roamed the nearby forests and farmlands. Once, when Jane was 5, her brother Tommy summoned her to the driveway and told her to stand still and close her eyes. “The next thing I knew, he had poured a giant ring of gasoline around me and lit it on fire. He started cracking up and ran away,” she recalled. Jane stood in the center of the driveway, screaming at the top of her lungs. “The consequence of a motherless childhood,” she said.

What’s more, money was tight. Raising seven kids on the wages of a public servant was a challenge, even with GI benefits. When Jane was around 13, John went bankrupt, losing everything, an experience Jane only later understood as humiliation. Amid all the turmoil, the family was changing. Most of Jane’s older siblings had moved out, and her father had remarried. The McAleveys moved out of the family’s tumbledown farmhouse and moved in with John’s new wife, who immediately imposed austerity measures. Her first step was to get rid of Jane’s beloved pony—a declaration of war.

Shortly thereafter, her stepmother proposed adopting Jane. One afternoon, she sat Jane and her father down in the living room, sliding the doors closed and announcing two reasons for her decision: She’d always wanted a girl, and Jane was the only McAlevey young enough to still be civilized. Jane started laughing when she recounted this story. “Like, just listen to her,” she said. “She needs a lesson in a six-step organizing conversation, because that did not work. I mean, what were my issues in the room? Seriously.” Jane told her stepmother and her father she was not interested in the offer.

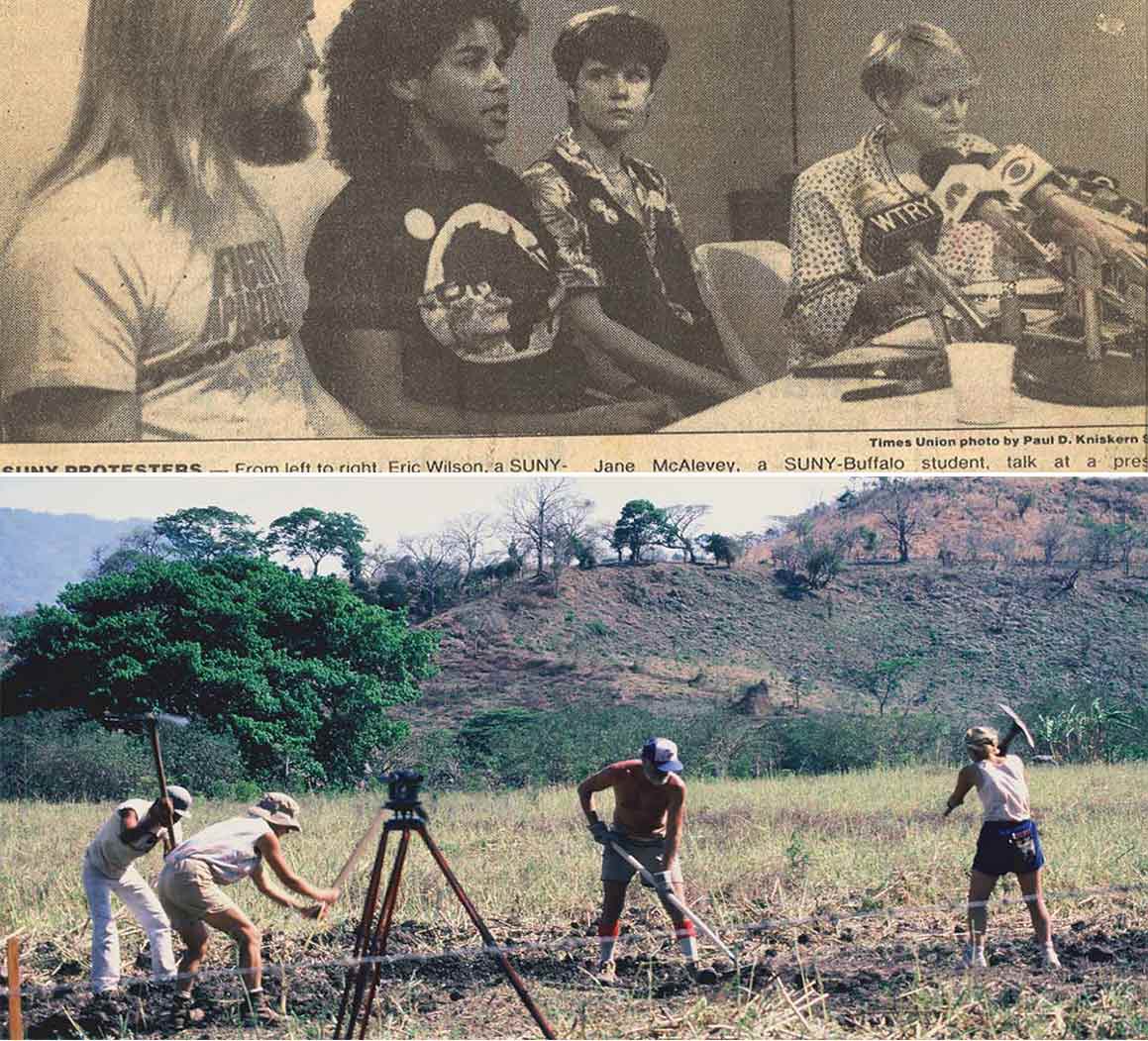

“And from then on, it was World War III,” Jane said. Within a few years, Jane had left home. She lived with her sister, and then enrolled in the State University of New York at Buffalo, where she almost immediately got swept into organizing, becoming president of the student body and leading a historic campaign for divestment from apartheid South Africa. Although she wouldn’t join the labor movement for another decade, Jane had already arrived as a preeminent organizer and strategist.

Her first union organizing campaign, for the AFL-CIO’s innovative multi-worksite organizing project in Stamford, Connecticut, was groundbreaking: Some 4,000 workers had their first union and contract—but even more, their efforts saved four public housing projects from demolition, won $15 million to renovate the units, and secured new ordinances mandating that any new developments in the city include a certain percentage of affordable units. The campaign also established what would become Jane’s hallmark style: big, bulging goals and a basketball-like execution plan—the precision of a thousand tiny repetitions; inviting people to touch their power, then watching them grab it for their own; the grinning, sweaty devotion to the team; the rapture of winning.

Eventually, during my visit that rainy April, it was time to watch the Warriors-Kings playoff. Politics might suggest that Jane should be a Kings fan—she’s a champion of the scrappy underdog, not the dynastic favorites. But her San Francisco fervor runs deep, and her face lit up when the line of blue-and-gold uniforms jogged onto the court. She muttered throughout the game, mostly to herself, but she also generously caught me up on the past decade of Golden State history. At one point, I asked her what her dream NBA position would be, imagining that she saw herself as a revered coach like Stephen Kerr or Phil Jackson. “The commentator,” she told me, eyes staring straight at the screen. “No, wait. The person who hires the commentator.” Ever the organizer, Jane didn’t need to be the one telling the story. But she also knew that nothing matters more than how the story gets told.

Jane was occasionally called—sometimes admiringly, sometimes exasperatingly—“the semantics czar.” Even the smallest words represented a fulcrum of power. Referring to “the union” rather than “me” or, better, “us” linguistically denoted it as a third party. Saying “Thank you” to workers patronized their efforts rather than affirming their ownership of their own struggles. Jane’s attention to this level of diction sprang from her 12-dimensional sense of strategy and her deep appreciation of the subtleties of human relationships. It also underscored one of her core teachings: Every engagement, every word choice, presented an opportunity either to exercise agency or to abdicate it. The whole world, all its words, was a campaign, to be won or lost.

This included being profiled in The New Yorker. Of course, that campaign’s objective wasn’t a contract or a raise, or sheer notoriety. The article, I eventually understood, was critical comms in an existential operation, its goals both grand and tragic: to win Jane more life in the face of impending death. In the best case, Jane believed, the article could catalyze some kind of cure, or at least a durable treatment, for her cancer. A top-rate doctor would read the article, she imagined, become deeply moved, and invite her into a novel medical trial, say a CAR T-cell treatment, that she had not previously qualified for. But for such a doctor to be convinced, Jane decided, the article would need to appear in print. Online would not do. Doctors aren’t squinting at The New Yorker on their cell phones, she huffed to me; they get the magazine sent to their beach houses, where they read it on their chaises longues.

Unfortunately for both me and Jane, that decision was not up to me. The matter rested, in part, on the strength of my writing, but also the timing of the article, the will of the magazine’s editorial board, the unfolding of concurrent global catastrophes. When I explained this to Jane, she harrumphed—a grunt somewhere between acknowledgment and disagreement. But she did not let the matter rest. A month or so before the article was finished, Jane pressed me again. She had recently been hospitalized, and we chatted by phone as she wandered through the hospital’s courtyard. Desperate for fresh air, she had sneaked out of her room. At one point during our conversation, she had to abruptly hang up—a security guard was approaching. When she called back, I told her I still had no information about whether the piece would appear in print. “Hmm,” she said, this time thinking out loud. “What do we know about the board? Who is on it? How do its decisions get made?” I mumbled something about my ignorance on the issue, but Jane did not heed. “If we were to draw a circle around David Remnick, who would be in it?” I nearly shrieked in wonder. She was, in real time, conducting a power structure analysis of the New Yorker editorial board. Everything was her organizing terrain.

The word “blitz” has a noun and a verb form. As a verb, it derives from the old High German word for “to flash.” This is Jane McAlevey, a means of illuminating what so often lingers in shadows: a people’s sense of their own power. As a noun, “blitz” refers to a rapid, nearly overwhelming use of force in war. Embedded in a blitz is a brutal paradox: The brevity of a blitzer’s life can be redeemed by the safeguarding of the lives of others. This is also Jane, a verb and a noun, an endless motion and a finite lifetime. Jane’s anticipation of her impending death came with blessings of its own: her turn to writing, and the volumes of books and teachings that will outlast her own breath; a tribe of mentees who will continue the work; the thousands of workers who have been changed by her belief in their power.

In March 2023, at the launch party for Jane’s latest book, Rules to Win By, held at the People’s Forum in New York City, one participant asked: How should we approach organizing drives in places with extremely high worker turnover, like Amazon or McDonald’s, where it’s nearly impossible to both train workers on the method and coach them to execute it before they’ve left? Though the question was ostensibly pragmatic, its essence was metaphysical: What do we do when we don’t have enough time?

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →The panelists, all serious organizers and among Jane’s keenest disciples, looked frantically at each other, whispering back and forth. No one seemed to know what to say. McAlevey, who had been seated among the audience, marched to the front of the room and took the mic. The panelists looked sheepish but relieved. “That’s not actually a barrier,” Jane said, bluntly. “We adapt the methodology and do everything more quickly. You just do it. We can still win.” The panelists nodded. One panelist, her inspiration apparently refreshed, took the mic to expound in more detail. Even one second is enough time to change the course of a game. Soon, the other panelists chimed in, too, offering their own experiences in this context. Jane sat back down. Her work here was done.