How the Far Right Won the Food Wars

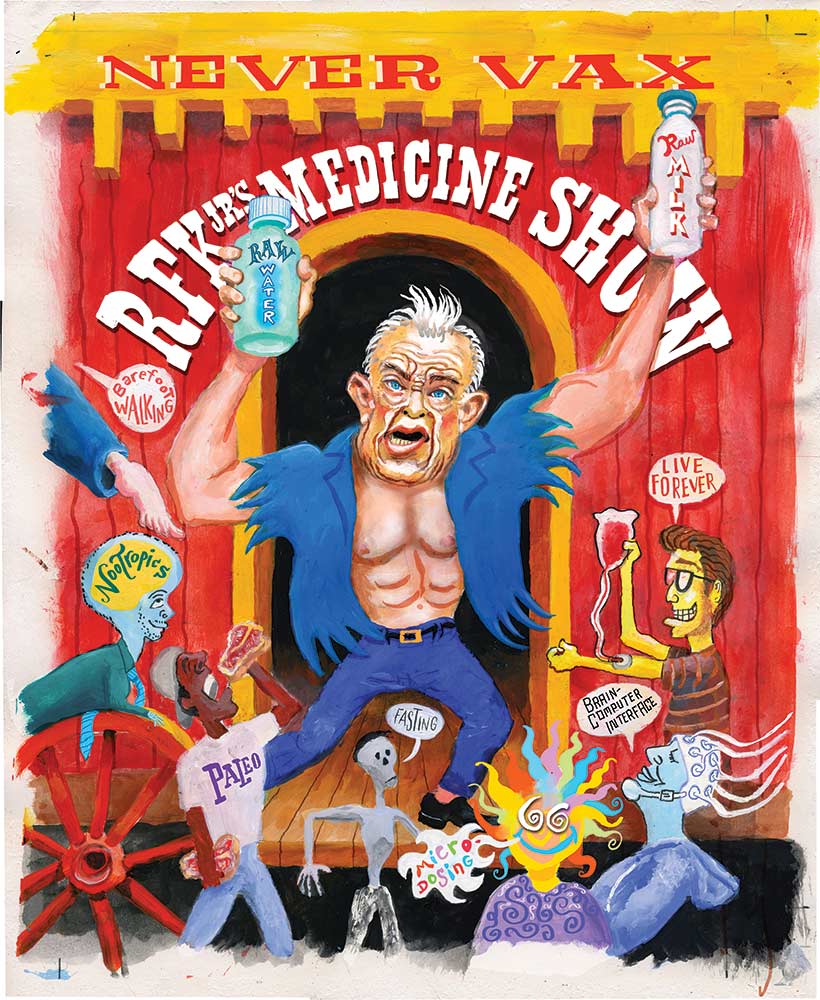

RFK’s MAHA spectacle offers an object lesson in how the left cedes fertile political territory.

On November 12, Health and Human Services Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr. gathered together health advocates, social-media influencers, and biohacking entrepreneurs at the White House for the Make America Healthy Again (MAHA) Summit. The panels featured no scientists, doctors, or academic researchers but were replete with CEOs, bloggers, and right-wing celebrities like the UFC president and mixed-martial-arts expert Dana White. The day-long conference included Dongjin “DJ” Seo, a cofounder of Elon Musk’s Neuralink, discussing the future of “brain-computer interfaces” and his vision for a cyborg humanity. The venture capitalist Bryan Johnson, known for receiving blood transfusions from his teenage son, pondered whether, with “biohacks” like these, his generation could be the first to become immortal. Vice President JD Vance, taking the stage to the tune of “Long Cool Woman” by the Hollies, spoke passionately on government overreach in the healthcare sector.

Speakers also discussed topics more typical of a public-health conference. Aidan Dewar, the CEO of the start-up Telenutrition, and the food blogger Vani Hari spoke on the health benefits of nourishing food and the dangers of additives and preservatives. The tech executives Farid Vij, Chris Altchek, and Sean Duffy discussed using their companies’ in-app technologies to manage chronic disease. Also addressed: the contraction of American lifespans and the dangers of alcohol and seed oils. The summit’s overall theme was the breakdown of American healthcare and how the industry needs to be disrupted and rebuilt from the ground up. Rebuilt, of course, through deregulation, with the bottom lines of conglomerates and tech start-ups taking top priority.

This spectacle, while sleazy and unsettling, was hardly a departure from the status quo. The MAHA conference was in many respects the logical outcome of long-standing US policy on public health, particularly nutrition. Few things are more elemental than food. But ever since the 1970s, when the idea of eating healthy came to prominence with the organic-food revolution, we’ve struggled as a country to address the structural problem of access to that healthy food. What we’ve tackled instead are problems of consumer choice. The lead-up to Kennedy’s circus of sci-fi fantasists and food bloggers provides an object lesson in how the left cedes fertile political territory to the right. Healthy eating—a cause that’s as foundational as they come—has gradually been put to pasture as a collective national project. Rather than addressing the working and living conditions of Americans that are at the root of the issue, one presidential administration after another has punted the problem to the free market.

Organic food as we know it is food that is cultivated by applying modern technology to traditional agriculture. An organic farmer might use a tractor, a harvester, or a milking machine but avoid harmful fertilizers, pest controls, or animal growth hormones. The early promoters of the organic-farming movement prioritized soil quality and the sustainability of agricultural practices. (The focus on the higher nutritional quality of organic foods came later, when the movement transformed into an industry.) The botanist Sir Albert Howard, sometimes considered the father of organic agriculture, wrote in his 1947 book The Soil and Health: A Study of Organic Agriculture, “All the great agricultural systems which have survived have made it their business never to deplete the earth of its fertility without at the same time beginning the process of restoration.” Howard sought to realign the interests of humanity with those of nature in agricultural practices as a way to protect our food systems from wasteful industrial consumption. Along with other mid-20th-century scientists, such as the microbiologist Masanobu Fukuoka, he was responding to wasteful, soil-depleting industrial techniques and the use of synthetic pesticides and fertilizers that would only become more advanced, widespread, and dangerous as the century progressed.

In the 1960s, widespread concerns about the environmental effects of pesticides like DDT boosted interest in organic farming. The conservationist Rachel Carson made many Americans aware of the dangers of pesticides for the first time in her 1962 bestseller Silent Spring. Highlighting the egotism and shortsightedness of industrial pesticide use, Carson wrote, “How could intelligent beings seek to control a few unwanted species by a method that contaminated the entire environment and brought the threat of disease and death even to their own kind?” Given these new environmental concerns, the hippie counterculture of the late 1960s and early ’70s dovetailed neatly with the organic-farming movement. In The Omnivore’s Dilemma, the popular nonfiction writer Michael Pollan describes the organic farming of this era as “one of several tributaries of the counterculture that ended up disappearing into the American mainstream.”

As the public became increasingly environmentally conscious and organic farmers mounted a parallel back-to-the-land movement, a market for organic food burgeoned, especially on the West Coast. Starting in the 1970s, states like Oregon and California, where organic farming was taking off, responded by passing regulations that would allow products to be certified as organic. This labeling helped consumers distinguish these foods from their industrial counterparts. Upwardly mobile baby boomers in particular boosted this new industry. By the Reaganite 1980s, roadside raspberry stands that had sprouted during the Summer of Love had evolved into giant farming conglomerates, with their complement of lawyers and lobbyists. The now-vast and corporatized organic-food industry, working in conjunction with environmental groups such as Beyond Pesticides, lobbied Congress to establish a set of national industry standards that would define organic and govern the certification of organic foods. The Organic Foods Production Act of 1990 enabled the US Department of Agriculture to regulate food products under the National Organic Program and set standards for production and labeling, ushering in the booming industry we have today. The green-and-white “USDA Organic” sticker on egg cartons comes from the passage of this law.

After the Organic Foods Production Act was finally implemented in 2002, what had been a lifestyle confined mostly to left-leaning, health-conscious West Coast families became more mainstream. By the 2010s, supermarkets throughout the country were stocked with organic products from Earthbound Farm and Cal-Organic. These foods were, and continue to be, more expensive than their industrial alternatives. The USDA reported in 2016 that the price of organic food ranged from 7 percent higher for produce to a whopping 80 percent higher for eggs. At the same time, popular books like Pollan’s In Defense of Food (2008) and other best-selling books were promoting a new way of thinking about food systems. Farm-to-table dining became de rigueur in fine restaurants; beef had to be grass-fed, tomatoes heirloom, and chickens heritage-breed. This was the back-to-the-land moment for a certain strain of millennials, the era of urban-rooftop beekeeping and faux farmhouse weddings. Upper-middle-class urban millennials were canning preserves, pickling vegetables, and posting their creations on websites like Punk Domestics. “Grandma” aesthetics were all the rage, and children were given Victorian names like Emma and Ella and fed made-from-scratch meals that paid homage to a time before McDonald’s and microwaves. Traditional lifestyles, organic foods, and wellness were hip, and like most things that were in vogue in the 2010s, they were coded politically as left-wing.

Though there was nothing intrinsically wrong with the era of home preserves and “stomp, clap, hey” folk pop, these cultural trends had a very limited reach. The changes in lifestyle and diet were confined mostly to an urban American middle class. While new narratives about food and health persuaded many middle-class people to buy organic products and change the way they eat, locally sourced ingredients and grass-fed meats were available only in places with high concentrations of wealth. High-income neighborhoods had farmers markets and bespoke butchers, but poor ones remained food deserts. In the end, these lifestyle changes also turned out not to move the needle a whole lot when it came to public health. Across demographics, obesity rates continued to climb despite the new food culture, particularly in rural food deserts.

Since Kennedy’s confirmation hearing on January 29, 2025, numerous publications have drawn a connection between his Make America Healthy Again platform and former first lady Michelle Obama’s 2010 Healthy, Hunger-Free Kids Act. Both took aim at ultra-processed foods and sugary drinks and encouraged parents to feed their children more nourishing foods. Both attempted to address the country’s obesity and chronic-disease epidemics by encouraging healthy eating. While the Obamas’ health initiatives withered away after Donald Trump took office, the right has surged into the healthy-eating space. These public-wellness efforts quickly found purchase in the unregulated, conspiracist-filled world of supplements.

The rollout and design of the Obamas’ healthy-eating initiatives offer some clues as to how this happened. The Healthy, Hunger-Free Kids Act was a bipartisan effort to make school lunches more nutritious nationwide and to give poor kids better access to those meals. The law was the centerpiece of Michelle Obama’s Let’s Move initiative to combat childhood obesity, and it did attempt to tackle the legitimate problem of access among lower-income families. But typical of the Obama administration’s orientation toward public welfare, the program was a hodgepodge package that tried to sell itself to the public by partnering with big businesses, government agencies, and celebrities. Walmart committed itself to lowering the cost of fruits and vegetables. The Department of Agriculture rolled out MyPlate, a website that provides information on nutrition standards. Three million students were given access to in-school salad bars. School-lunch standards were improved, and more children were made eligible for free meals. Promoting the initiative, Beyoncé reworked her 2007 song “Get Me Bodied,” changing the title to “Move Your Body” for the first lady’s “Let’s Move!” flash workout.

This top-down initiative aimed to alleviate the poor nutrition of some of the most vulnerable Americans. Marginalized communities were given a much-needed boost in nutrition and food education. The Overton window was shifting left on whole foods. Like many other middle-class urbanites in Obama’s base (i.e., not the demographic the initiative was intended to reach), I was thrilled by this era’s food movement. Nutrition standards were improving, supermarkets were full of organic food, and American cuisine was being revolutionized. Meals at home and in restaurants even tasted better. It seemed like the dawn of a new era in healthy eating. Yet, in less than a generation, we went from in-school salad bars to MAHA’s biohacking entrepreneurs.

The Obamas’ glossy, well-publicized initiative, accompanied by a blitz of news items featuring the first lady taking gym classes and tending to vegetable gardens, had more than a whiff of bootstraps rhetoric about it, framing nutrition and exercise as matters of personal responsibility. It also coincided with an explosion in the availability of organic-food products in supermarkets around the country. Sales saw very healthy improvement throughout the 1980s and ’90s, reaching $7.8 billion in 2000. The Organic Foods Production Act vastly expanded the scale of the industry, and by 2024 the Organic Trade Association reported annual sales at $71.6 billion. The act was the result of years of lobbying by a consortium of organic-food companies. Some of these, such as Cascadian Farm and Eden Foods, had their origins in the left-leaning sustainable-agriculture and food co-op movements of the 1960s and ’70s.

Far from sparking the locavore revolution, the Obamas’ nutrition program instead attached their brand to the all-natural zeitgeist of the 2010s. Their signature wellness legislation was a bouquet of moderate, market-friendly reforms delivered during a boom in organic-food consumption. As with other Obama-era reforms, while it did address a real issue with serious, if modest, changes, it didn’t have the reach to appeal to the general population.

In the media, the small improvements the legislation was able to make were drowned out by the pandemonium of the culture wars. Republicans met the West Wing’s organic-eating initiatives with cartoonish diatribes against the “nanny state.” Sarah Palin protested an initiative that would limit the number of sweets allowed in Pennsylvania schools by staging a delivery of sugar cookies to a Christian school in Bucks County. Right-wing outlets blamed Michelle Obama’s exercise regimen for an uptick in pedestrian deaths after people started walking more. Centrist liberals, meanwhile, responded in kind by mocking obese, unhealthy red-state Republicans. The trim, disciplined Barack Obama, who snacked on seven almonds a night in the White House, was regularly contrasted on liberal talk shows with the corpulent Chris Christie, Mike Huckabee, or Donald Trump. The food movement became yet another dreary (class) signifier in the culture wars: consumer goods you could buy—or conspicuously mock and avoid—to signal allegiance to your political team (and, implicitly, your ranking in the socioeconomic food chain).

Today, the market shares of organic food and supplements have seen explosive growth and are both predicted to more than double in the next seven years. Despite these booming industries, Americans’ health has not improved. The Obama administration achieved modest, temporary decreases in obesity rates for very young children, but rates overall have continued to climb. However well-intentioned the Healthy, Hunger-Free Kids Act was, it failed to have an impact on health in a way that felt palpable to most people. While the tech CEOs at the MAHA Summit expounded on the health benefits of fruits and vegetables, President Trump, in addition to attempting to roll back many of the provisions of Obama’s health act, has cut the benefits that allow people to actually buy fruits and vegetables. Comparing the two administrations, most of us would choose inadequate help over active harm. But it was partly because a Democratic administration’s interventions in wellness yielded such weak results that once the government lurched rightward, so did health consciousness.

While the food movement in this period was associated with left-wing politics, at the ever-encroaching political fringe, a growing cadre of health-obsessed libertarian entrepreneurs promoted radical methods of self-improvement. Lifestyle authors like Timothy Ferriss and Mark Sisson popularized eating like paleolithic humans, barefoot walking, intermittent fasting, and Ironman competitions. CrossFit, the high-intensity gym begun by the staunch libertarian Greg Glassman, went from 13 gyms in 2005 to 13,000 in 2016. Obesity statistics were getting worse, and Gen Xers and millennials were aging. While Bernie Sanders and the small organized left called for Medicare for All, the market responded to new health concerns with a wild cornucopia of supplements and health fads, from benign bone broth to the more dubious nootropics, or “cognitive enhancers.”

Eventually, radical self-improvement became popular in corporate America, particularly in Big Tech. In private life, for the upwardly mobile liberal, it was the era of sauerkraut crocks and handlebar mustaches. But in the workplace, it became the era of standing desks, biometric screenings, corporate microdosing retreats, and mindfulness apps. According to Forbes, by 2017, Google, Intel, Aetna, and General Mills were offering mindfulness training to employees to optimize performance. Workers were encouraged to improve their health in order to be more productive at their jobs and make more money for their employers. In healthcare, with employer health-insurance premiums and deductibles rising rapidly, Americans turned to a chaotic array of new products to keep away from the doctor. The US supplement market grew steadily throughout the 2010s, rising from $11.5 billion in 2012 to $71.6 billion in 2024, notably accelerating during the pandemic lockdown period and beyond. Fueled by often-unverified health claims, products touted by extremists of different political stripes, but much more successfully publicized by the far right—such as raw milk, colloidal silver, and unfluoridated water—have skyrocketed in popularity since the pandemic.

In May 2025, Kennedy drank shots of raw milk in the White House with the podcaster/influencer Carnivore MD. Raw milk is milk that has not been pasteurized—that is, heated to 145 degrees Fahrenheit, killing all bacteria. Partly because raw milk is heavily regulated and farms that sell it are routinely raided by the FDA, it has become a pet cause of the libertarian “food freedom” movement, which seeks to liberate the purchase and consumption of food from restrictions and regulations. Unlike many of the products favored by food libertarians, raw milk has advocates on the left, including Michael Pollan. Its fans claim that it has health benefits, including the ability to decrease rates of allergies and asthma, and they can cite scientific research that backs them up. Today’s right-wing raw-milk advocates, however, don’t seem particularly concerned with food safety. National Review, downplaying the role raw milk played in the spread of avian flu in 2024, argues that we should be able to buy what can kill us if we want to, putting milk in the same category as cigarettes.

Proponents of raw water—untreated, unfiltered, and unsterilized drinking water—are wary of tap or filtered water because of its fluoride and chlorine content and because of possible contamination from any lead pipes it may have traveled through. And they believe that, like raw milk, it contains healthy bacteria that can prevent diseases. The raw-water trend was mainly pre-pandemic, especially among the health-conscious Silicon Valley tech community, but the fear of fluoridated water has persisted in alternative-health sectors. Kennedy has called on states to ban the fluoridation of tap water. Fluoridated water protects against tooth decay, and while over-fluoridation can damage teeth and bones, anti-fluoride activists, citing mostly inconclusive studies, maintain that it can cause bone cancer, cognitive impairment, and ADHD. For conservatives, it’s another example of the government inserting itself into our lives and forcing a dangerous poison into our bodies.

Today, instead of a healthier population, we have a right-wing, performance-enhancement-oriented “health” movement full of anti-vaxxers, MAGA influencers, and nootropic enthusiasts. While liberal urbanites no longer dine on grass-fed burgers and duck-fat fries beneath bare Edison bulbs, tradwife momfluencers now feed sourdough pancakes to their broods of unvaccinated children. The distinction turned out to be cosmetic. Both of these demographics make choices about how they want to be perceived and how they want to spend their disposable income. And both invoke their consumption habits to score points against the other side. Citing a study showing that conservative men have higher levels of testosterone, JD Vance told Joe Rogan last year, “Maybe that’s why the Democrats want us all to be, you know, poor-health and overweight is because it means we’re going to be more liberal, right? If you make people less healthy, they apparently become more politically liberal.” No longer the party of the Big Gulp–guzzling fatso, the young Chads of MAGA want you to know that they’re stacked supermen and their bodies are temples.

A recent article in the libertarian magazine Reason argued that the left bungled food messaging because of wokeness—that popular cookbook authors were canceled because of cultural appropriation and that influencers couldn’t encourage healthy eating because that would count as fat shaming. While social media was, and continues to be, a hotbed of culture-war goofiness, people yelling about lentils in the comments section of Jezebel hardly accounts for the rise of RFK Jr. The contemporary food movement’s rightward orientation isn’t really a reaction to left-wing food philosophy. In fact, despite its cultural coding, the food movement of the 2010s was never especially left-wing to begin with. Instead, with both liberal and conservative factions proposing we shop our way to better health, is it any wonder that the side that has always been better friends with big business won the food-messaging war?

The Obamas’ healthy-eating initiatives were full of programs designed to help motivate people to make good food choices. One example was a partnership with Walmart to nudge shoppers toward healthier foods through new packaging. According to Partnership for a Healthier America, a nonprofit created in conjunction with the initiatives, by the end of 2015 Walmart had reduced the amount of sugar in its branded packaged foods by 10 percent and had saved Americans $1 billion per year by lowering the prices of fruits and vegetables, as well as opening or renovating hundreds of stores in food deserts. Walmart also closed some stores during this period, creating new food deserts, but overall there was a net improvement in access. It’s interesting, then, that this massive healthy-eating initiative undertaken by the nation’s largest grocery chain, alongside new standards and legislation, did not result in lower obesity rates.

Rather than offering a cornucopia of health, the opening of a Walmart store in a poor community is correlated with a 2.3 percent increase in obesity levels. This makes sense when you consider that Walmart also sells cheaper, calorie-rich processed food in bulk. That’s the kind of food that Walmart’s own poorly paid employees can afford. As the largest private employer in the nation, Walmart’s labor practices impoverish some of its own shoppers—and in turn impact their food choices. If you’re underpaid and overworked, or underemployed and dead broke, the fact that healthy food is available doesn’t mean it’s accessible.

The left-leaning food movement had a real opening to foment collective change. But its reach mostly stopped at the cash register. It was about making good choices as individuals in the free market and never about the choices made for us by our employers. It never looked at how our work lives inform how and what we eat. Between 1965 and 1995, time spent on cooking decreased by 40 percent. During the same period, union membership declined, the Democratic Party abandoned its working-class base, and both parties presided over the shrinking of the middle class. As the labor movement collapsed and our government marched rightward, our ability to nourish and care for our bodies declined. In 2023, according to an analysis by the Auguste Escoffier School of Culinary Arts, 55.7 percent of all food purchased in the United States was prepared outside the home. Today, there may be more organic produce in supermarkets, but our living and working conditions largely prevent us from cooking and eating fresh and nourishing whole foods. With the food industry pressing junk food on us the moment we leave the house, and the hours we spend working increasing alongside the costs of food, housing, and childcare, it’s no wonder that we continue to stress-eat our way to poor health.

The raw-milk-obsessed tech bros who have taken up the mantle of healthy eating have even fewer solutions to the wellness crisis than the Obama-era liberals did. Tradwife influencers might show off on TikTok how well they care for their five children while slow-braising a stew, but many celebrity social-media stars are members of the 1 percent, and their cooking idylls are fantasies for most working Americans. Right-wing wellness, like its liberal equivalent in the 2010s, exists mostly in the realm of individualistic aspiration. It presents a fantastic quest for what Naomi Klein describes in her 2023 book Doppelganger as the “you as you imagine you could be, with enough self-denial and self-discipline, enough hunger and enough reps. A better, different you, always just out of reach.” MAHA’s biohacks, supplements, and chronic-disease-management apps make bodily perfection seem possible, but they will not shorten the workday. They won’t make the lives of gig workers or the underemployed less frenetic and uncertain. Unwilling to address our living and working conditions, the right just offers another health fairy tale.

We know for certain that RFK Jr. isn’t going to make America healthy again, especially not with defunded and hollowed-out government health institutions. We also know that the Democratic Party, as it is currently composed, won’t do much better—not with a leadership that’s uninterested in pursuing the kinds of big government interventions that could actually transform the health of Americans. We also know that if we continue to do nothing, our food systems will change all on their own. The climate crisis is already impacting the global food supply. Because of rising temperatures, corn, soybean, and wheat production could decline as much as 50 percent by the end of the century. Industrial food production itself also contributes massively to climate change, from cattle ranching in the Amazon increasing greenhouse gases to food companies contributing 20 percent of global emissions merely in the transportation of food.

Fortunately, there is some light on the horizon, courtesy of another trend that locked into place in the long 2010s. The decade that started with home brews ended with a renewed interest in democratic socialism and a resurgent labor movement. My own evenings of slow-braising were replaced by meetings with the Democratic Socialists of America. I put my pickle jars away and bought a bullhorn. I learned that a real food movement can’t just be about what we put in our bodies. More important than our consumer choices are the lives of the workers who grow the food, slaughter the animals, and drive the refrigerated trucks. Food systems will not be improved by individuals buying water-wasting organic cashews harvested by underpaid migrant workers in deadly temperatures.

The left lost control over food messaging not because it got too woke but because it stagnated in a pool of contradictory consumer choices. To get it back, we need dynamic lawmakers willing to embrace big societal fixes that ensure that our food systems are just, safe, and sustainable. To have a shot at radically transforming the way we eat, we need a climate movement that incorporates workers, farmers, consumers, climate scientists, labor unions, and activists. To be sure, we do still need access to healthy food through programs like New York Mayor Zohran Mamdani’s city-owned grocery stores—“a public option for produce”—to bring wholesome, inexpensive food into urban food deserts. But to eat well, we not only need access to inexpensive produce but also the time away from work to cook healthy meals for our families. We need food grown by fairly paid, unionized workers using sustainable agricultural techniques. So long as the reins of government are held by those who profit from our bad health and who are driving the climate crisis, it seems unlikely that our food systems or our health will improve. To have a serious impact, we need more than Michael Pollan’s intellectual revolution in food systems. A full restructuring of our lives, both at work and at home, in the grocery store and on the farm, is needed to pull our world and our bodies back from the brink.

Your support makes stories like this possible

From Minneapolis to Venezuela, from Gaza to Washington, DC, this is a time of staggering chaos, cruelty, and violence.

Unlike other publications that parrot the views of authoritarians, billionaires, and corporations, The Nation publishes stories that hold the powerful to account and center the communities too often denied a voice in the national media—stories like the one you’ve just read.

Each day, our journalism cuts through lies and distortions, contextualizes the developments reshaping politics around the globe, and advances progressive ideas that oxygenate our movements and instigate change in the halls of power.

This independent journalism is only possible with the support of our readers. If you want to see more urgent coverage like this, please donate to The Nation today.

More from The Nation

How Stephen Miller Became the Power Behind the Throne How Stephen Miller Became the Power Behind the Throne

Miller was not elected. Nor are he or his policies popular. Yet he continues to hold uncommon sway in the administration.

The Racist Lie Behind ICE’s Mission in Minneapolis The Racist Lie Behind ICE’s Mission in Minneapolis

It was never about straightforward enforcement of immigration law.

Sunnyside Yard and the Quest for Affordable Housing in New York Sunnyside Yard and the Quest for Affordable Housing in New York

Constructing new residential buildings, let alone those with rental units that New Yorkers can afford, is never an easy task.

How Capitalism Transformed the Natural World How Capitalism Transformed the Natural World

In her new book, Alyssa Battistoni explores how nature came to be treated as a supposedly cost-free supplement of capital accumulation.

Bad Bunny’s Technicolor Halftime Stole the Super Bowl Bad Bunny’s Technicolor Halftime Stole the Super Bowl

The Puerto Rican artist’s performance was a gleeful rebuke of Trump’s death cult and a celebration of life.

Drag Can Save a Life in New York City—if People Show Up Drag Can Save a Life in New York City—if People Show Up

Black and trans drag performers are crowdfunding to survive in one of the most expensive cities in the world.