Bookworms and Fieldworkers

How did Marxism become Marxism?

How Did Marxism Become Marxism?

A new book examines a set of thinkers and activists who helped transform a set of radical ideas into a political tradition.

In the years leading up to the outbreak of the 1905 revolution in Russia, Eduard Bernstein—the spirited German advocate of socialist revisionism—warned his Marxist colleagues about the dangers of an “almost mythical faith in the nameless masses.” More skeptic than firebrand, Bernstein worried that Karl Kautsky and other leaders of the international socialist movement placed too much confidence in the spontaneous emergence of an organized and disciplined working class: “The mob, the assembled crowd, the ‘people on the street’…is a power that can be everything—revolutionary and reactionary, heroic and cowardly, human and bestial.” Just as the French Revolution had descended into terror, the masses could once again combust into a violent flame. “We should pay them heed,” Bernstein warned, “but if we are supposed to idolize them, we must just as well become fire worshippers.”

Books in review

The Invention of Marxism

Buy this bookAmong the votaries of European socialism, Bernstein has seldom enjoyed much acclaim, not least because he symbolized the spirit of pragmatism and parliamentary reform that ended up on the losing side of the debates that roiled the socialist movement in the decades preceding the Bolsheviks’ victory in 1917. For historians who are less partisan, however, the time may well seem ripe for a new appraisal—a revision of revisionism—that casts Bernstein and his reformist wing in a more favorable light.

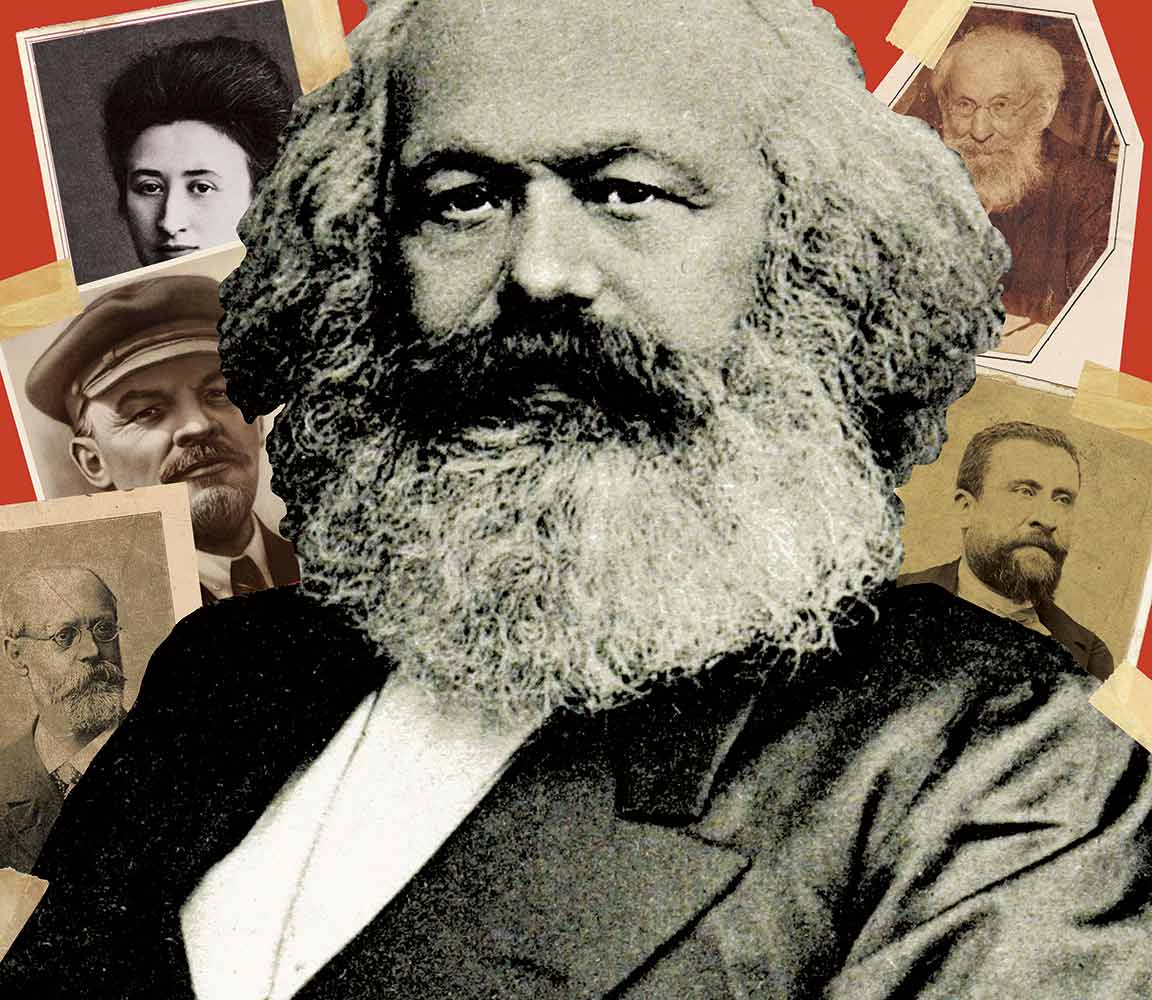

This is the ambition of Christina Morina in The Invention of Marxism, recently translated into English by Elizabeth Janik. A study of Bernstein, Kautsky, Lenin, Jean Jaurès, Rosa Luxemburg, and other early Marxist luminaries, the book bears a rather breathless subtitle—“How an Idea Changed Everything”—that is far too ambitious for any author, but it is nonetheless a searching account of Marxism’s early days. Although it offers no certain answers as to what the “idea” of Marxism really consists in, it does provide a welter of personal and biographical detail that enriches our sense of Marxism’s varied history and the lives of its party leaders .

How should we write the history of Marxism? Over the past century, when political opinion has been sharply divided on the meaning and legacy of the socialist tradition, historians have felt compelled to choose one of two modes of narrative: either triumphant or tragic. Both of these approaches are freighted by ideology, yet neither has permitted a truly honest reckoning with the political realities of the Marxist past.

Morina, a scholar whose training reflects the methods of social and political history associated with the University of Bielefeld in Germany, where she now works as a professor, has set out to write a history that avoids strong ideological verdicts and places a greater emphasis on the sociology of intellectuals and the details of the Marxists’ personal lives, a method that also draws inspiration from the new trend in the history of emotions pioneered by scholars such as Ute Frevert. No doubt the book also reflects her own experiences as a child in East Germany, where she witnessed the “absurdities and inhumanity” of an authoritarian state that was arguably socialist in name only.

The fruit of her efforts is a group biography that explores the fate of nine “protagonists” from the first generation of the European socialist movement following the death of Karl Marx in 1883. Morina weaves together their personal and party histories with unusual skill, though without quite telling us “how an idea changed everything.” Perhaps the key difficulty is the method of prosopography itself, which fractures the book into individual life stories and leaves little room for a continuous political narrative. Those who are not already familiar with the broader history of European socialism will find it difficult to understand how the various national parties (in France, Germany, Austria, and Russia) all participated in a common struggle. But there is a case for her approach nonetheless, as it leads to some unique insights. By examining how personality and emotion shape one’s political commitments, Morina paints a portrait of Marxism less as a specific theory than as a shared language and a set of informal dispositions that spawned a variety of competing interpretations. Her nine protagonists were not, she explains, gifted with a sudden revelation of the truth. Each underwent a slow and emotional process through which the ideas of Marx became a common framework for explaining and evaluating political events.

While we now take this framework for granted as Marxist doctrine, Morina notes that the creation of Marxism was itself “a vast political project” that developed only gradually. The term gained “ideological meaning and political heft” only in the 1870s and 1880s, as works by Marx and Engels spread across the world in various editions and translations. For Morina, this means that the task of the social historian is to understand how those works were received, often on a case-by-case basis. The result is a book that tells us a great deal about these early Marxists as individuals, though much less about Marxism as a comprehensive theory or idea.

Historians tend to emphasize the social and biographical settings of an idea, a method that is unlikely to satisfy philosophers or social theorists, who are concerned chiefly with the intrinsic validity of arguments. But given Marxism’s own interest in materialism, these contexts are something that historians cannot afford to ignore. They also point to an irony within the tradition, for if Marxism is an idea, it’s only because of the intellectuals who carried it forward and helped ensure its longevity—and many (though, of course, not all) of these intellectuals were by origin and education members of the bourgeoisie, not members of the working class lionized in Marxist theory.

Morina is acutely aware of this irony, and it informs all of her judgments in the book, some of them subtle, others overt. Running through The Invention of Marxism is a powerful current of unease about the “abstraction” of theory and the great distance that separated some of Marxism’s most esteemed theorists from the world they wished to understand. Although they were passionate in their principled commitment to the working classes, they often knew little about the workers’ actual lives, and at times they responded with revulsion—or at least discomfort—when exposed to the real suffering of the proletariat for whom they claimed to speak.

Morina takes special care to note that many of the party theorists in her tale enjoyed the rare privilege of a university education at a time when less than 1 percent of secondary school students in Western Europe went on to study at university. Karl Kautsky, a leading member of the German Social Democratic Party, was born into a home of writers and artists, and his parents were highly committed to his schooling. Victor Adler, a leader of the Social Democratic Workers’ Party of Austria, was a practicing physician as well as a publisher—he founded Gleichheit (Equality), the first socialist party newspaper in the Hapsburg Empire. Rosa Luxemburg studied at the University of Zurich and was by all reports an exceptionally precocious child whose parents grew prosperous thanks to her father’s success as a timber merchant; her theoretical acumen and political passion elevated her to prominent seats, first in the German Social Democratic Party and later in the Independent Social Democrats, the Spartacus League, and the Communist Party. Jean Jaurès, born in the South of France, rose to the top of his class and attended the École Normale Supérieure, where his classmates included Émile Durkheim and Henri Bergson, before he emerged as the most influential leader in the French Socialist Party.

The other protagonists in Morina’s tale enjoyed equal or even greater advantages. Vladimir Ulyanov (later Lenin) was born into a prosperous Russian family that owned estates; his father, a liberal teacher elevated to the post of school inspector, was eventually granted a title of nobility, while his mother came from a family of landowners with German, Swedish, and Russian origins and spoke several languages. Georgi Plekhanov, the “father of Russian Marxism,” had parents who owned serfs and belonged to the Tatar nobility; following the Emancipation Edict of 1861, Plekhanov’s family fell into financial decline, but thanks in part to his mother, he enjoyed a very strong education. Only two figures in Morina’s book were not the beneficiaries of wealth and education: Jules Guesde (born Bazile), later a major figure in French Marxism and socialism and an opponent of Jaurès; and Eduard Bernstein, whose father was a plumber and who never attended university and worked as a bank employee to support his activities in the German Social Democratic Party.

These protagonists, most of them members of the middle class, belonged to what Morina calls a “voluntary elite.” Her group study, though often engaging, remains poised in an uncertain space between intellectual history and party chronicle, without ever truly resolving itself into a satisfactory version of either. Needless to say, this ambivalence may be baked into the topic itself, since Marxism is perhaps distinctive in its contempt for mere theorizing and its constant refrain that we must bridge the gap between theory and practice. After all, has there ever been a Marxist who did not insist that their ideas were not correlated with material events? Morina, though hardly a Marxist in her methods, suggests that her study exemplifies the genre of Erfahrungsgeschichte, or the “history of lived experience.” Experience, however, is itself a concept of some controversy, since it hints at some bedrock of individual reality beyond interpretation and deeper than mere ideas. And this would seem to be Morina’s point: By turning our attention to the biographical and emotional history of the European socialist tradition, she hopes to remind us that Marxist intellectuals were not bloodless theoreticians but human beings caught up in the same world of passions and interests they wished to explain.

Her group portrait comes alive most of all at moments when its protagonists encounter one another in friendship or debate. Before theoretical disagreements drove them apart, Bernstein and Kautsky sustained a close friendship: They went swimming together in Zurich and enjoyed the outdoors with “a text by Marx at our side.” In 1881, Kautsky sought the guidance of both Marx and Engels and even wrote to his mother about Marx’s daughters, who (in Morina’s words) “unfortunately were already married.” Marx dismissed Kautsky as an intellectual mediocrity who was little more than “a born pedant and hair-splitter in whose hands complex questions are not made simple, but simple ones complex.” This did not deter Kautsky from forging a close personal bond with Engels that eventually established him as the official legatee for the papers of both men when Engels died in 1895.

Though Kautsky would acknowledge that Capital was “more powerful” than anything that Engels had managed to write, his relationship with Engels would continue to inspire and shape many of his own insights into Marxism. Kautsky’s 1887 book The Economic Doctrines of Karl Marx in fact concludes with a bracing line from Engels that communism will mark “humanity’s leap from the kingdom of necessity to the kingdom of freedom.”

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →Engels’s influence on Kautsky and the “orthodox” Marxism avowed by the Second International can be found not just in citations. A theme that Morina returns to throughout her book is how many of these socialists sought to interpret Marxism as an objective science. “The co-opting of ‘science’ by Marxist social analysis,” she writes, “may have been the most effective political idea of social critics on the left in the nineteenth century. It turned Marx’s theses into Marxism, and an intellectual worldview into a political truth.”

The idea of a “scientific Marxism” grew in popularity among theorists like Engels, who praised Marx at his friend’s graveside as the Darwin of the social world. But it also became a common view among Marx and Engels’s heirs. In the era of electrification and rampant technological expansion, a vague kind of positivism gained in authority among socialists, moving many Marxist theoreticians to claim that Marxism, too, could enjoy the prestige of a science no less than that of the natural sciences such as physics and biology. Morina does not examine this view in much depth, and today very few Marxists would wish to defend the notion that Marxism is a strict science that discovers unbending or universal laws. All the same, she recognizes that the ambition to portray Marxism as scientific can help us to appreciate why it caught fire as a cultural and political ideology. In this respect, she treats Marxism no differently than a social historian might treat other systems of belief: To explain its ascendancy, she looks at its motivational power, not its claims to truth.

Readers who are invested even marginally in the truth claims of Marxism will find much to value in Morina’s narrative, but it may also leave them confused. The difficulty is due to her sociological method, which on the one hand seeks to explain Marxism chiefly as an affective framework for political mobilization but on the other hand frequently refers to social “reality” as if it were the unproblematic and decisive factor when it comes to categorizing and judging the book’s protagonists. She proposes that we divide her nine Marxists into three types: “fieldworkers,” “adventurers,” and “bookworms.” The fieldworkers, such as Adler, Bernstein, and Jaurès, base their knowledge on “firsthand experiences,” she tells us, and because they are “on site, in the middle of things,” they tend to understand Marxism more as a “moral principle” than as a “dogma.” The adventurers, like Lenin and Luxemburg, live as “activists and agitators,” even if their efforts land them in exile, where they nourish “outrage more than empathy” and where Marxism becomes an “emotional and intellectual home.” Meanwhile, the bookworms like Kautsky form their worldviews far from the scene of action; their workplace is the “desk, office, or library.” In affect, they tend to be “sober and matter-of-fact, or even cold and calculating.” For them, Marxism is not a matter of lived experience but a “theoretical structure.”

Such broad characterizations may remind the reader of Isaiah Berlin’s well-known distinction (borrowed from the Greek poet Archilochus) between hedgehogs and foxes. According to this zoological schema, a fox knows many things, while a hedgehog knows one big thing. Morina’s typology, like Berlin’s, comes freighted with strong judgments and implies a preference for what Berlin once called a “sense of reality.” Morina, too, disdains the hedgehogs and admires the foxes, the worldly fieldworkers who shape their ideas based on lived experiences rather than single ideas.

To be sure, Morina’s distinctions are themselves a set of abstractions: They carve up the intellectual sphere into simplified types that hardly capture the complexity of social reality. But it is when she turns to her adventurers and bookworms that this becomes particularly clear, especially when she examines the lives and personae of Luxemburg and Lenin, neither of whom appears in a favorable light. Luxemburg, in Morina’s estimation, was an ideologue who loved humanity from afar but disdained the poor and the suffering when they pressed too close. Lenin, she tells us, was no less distant from the working class; his politics came from his hatred for bourgeois society. Only the fieldworkers—Adler, Bernstein, and Jaurès—emerge from her analysis with their reputations intact.

The portrait of Bernstein, in particular, may arouse the most interest today. A pragmatist at heart, Bernstein gradually lost his taste for violent struggle and came to believe that participation in parliamentary democracy was the best means for socialists to improve the lives of the working class. Hence his famous slogan (as he restated it in his 1899 essay on the tasks of socialism): “The movement means everything for me and…what is usually called ‘the final aim of socialism’ is nothing.”

Luxemburg, like Kautsky and many others, found this sentiment intolerable, and she thus denounced Bernstein’s position as “opportunism.” In her 1900 pamphlet “Social Reform or Revolution,” Luxemburg chastised Bernstein for abandoning the movement’s very purpose:

But since the final goal of socialism constitutes the only decisive factor distinguishing the Social-Democratic movement from bourgeois democracy and from bourgeois radicalism, the only factor transforming the entire labor movement from a vain effort to repair the capitalist order into a class struggle against this order…the question: “Reform or Revolution?” as it is posed by Bernstein, equals for Social-Democracy the question: “To be or not to be?”

Morina typically takes care to maintain the neutral posture of a historian who is more interested in understanding than in moral judgment. But when we come to the debate over socialist revisionism that shattered the socialist parties in the years preceding the First World War, she expresses a subtle preference for Bernstein over Luxemburg. Some readers may feel that her judgments about Luxemburg depend rather too much on personal detail. Luxemburg is often eulogized as the tragic martyr of European communism, not least because she died a brutal death at the hands of the Freikorps in 1919. But Morina mines facts from her life and her private correspondence to paint a picture of Luxemburg that is far less appealing: The cofounder of the Spartacus League appears here not as a heroine but as a somewhat cold individual who regarded the suffering of others with “striking ambivalence.”

Whether or not one agrees with Morina’s characterization of Luxemburg, it does feel in these passages as though she is putting her finger on the scale a bit—and in Bernstein’s favor. It is hardly obvious that an individual’s persona should play a role in our judgment of their ideas and their contribution to major political events. What matters, after all, is not whether we happen to find Luxemburg personally appealing, but whether her stance in party debates over theory and policy was one we consider sound. Unpleasant people can have good ideas, just as pleasant people can have bad ones.

Notwithstanding these occasional quarrels with Luxemburg and some of her other protagonists, Morina offers an original portrait of Marxism’s invention, one that encourages us to reconsider the role of the “moderates” in the history of European socialism. Even if Morina were not as sympathetic to Bernstein as she is here, he would still stand out as one of socialism’s unsung and unlikely heroes. Although his proposals earned him only derision among the more orthodox theorists and officials in the communist movement, it was Bernstein’s somewhat drab and reformist style of social democracy that survived as the model for parties on the European left well into the mid-20th century, when more militant groups had dwindled in power and influence. As it turned out, the idea of a socialist state governed by a single party was a recipe for dictatorship, not democracy. The various socialist parties in Europe that swelled in membership did so only when they abandoned their militant rhetoric and took their place as parliamentary-style organizations that competed with other parties in free elections. This pragmatic strategy may not have realized the utopia of socialism’s dreams, but it contributed to robust social democracies and welfare states that vastly improved the lives of everyday people, and it also avoided the massive waves of violence and murderous reprisal that ensued whenever the forces of revolution and counterrevolution confronted each other in civil war.

Marxist orthodoxy, meanwhile, ended up a victim of its own absolutism. Even after Stalinism and the suppression of democratic movements in Hungary and Czechoslovakia, many exponents of communism refused to denounce the Soviet bloc on the dubious grounds that it was still necessary to choose between “real existing socialism” and the capitalist West. Meanwhile, the record of human rights violations and the torture and harassment of dissidents only grew more obvious to anyone who was not blinded by ideology. All of this has done far more harm to the legacy of Marxism than any of the theorists who strayed from the orthodox path.

To be sure, in recent years those socialist and social democratic parties that have moved to the political center have lost much of their prestige. Both the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD) and the Parti socialiste (PS) in France have hemorrhaged votes as their members have shifted to the political center or to new parties on the left that are either more “green” in their policy aims or more militant in their calls for class struggle.

Morina does not extend her narrative into more recent times: She confines The Invention of Marxism chiefly to the “golden age” of European socialism that preceded the Bolshevik revolution. Of the three “fieldworkers” in her analysis, two were dead by the end of the First World War. Jaurès was assassinated in 1914, and Adler died in Vienna in 1918, on the very last day of the war. Only Bernstein survived through the 1920s; he died in Berlin in late 1932, at a time when the communists and the Nazis were fighting each other in the streets. By that point, however, Bernstein was hardly an active participant in the socialist movement.

Already by 1903, Bernstein had been pushed aside, and at the party conference in Dresden that year, he was denounced for revisionism. Later, in an essay on his role in the revisionism debate, Bernstein admitted that he had not fully grasped the “spiritual” meaning of his dissent or the emotional significance of the word “revolutionary.” Although the SPD was not in fact a revolutionary party, for many years its revolutionary ideal continued to shine as an inspiring beacon, for the working class and especially for the SPD’s membership. Revolution “marked the line that distinguished the party they esteemed from all other parties” and gave the SPD its “distinctive worldview.”

Perhaps Bernstein was right, but if so, he may not have grasped the deeper and more ambivalent implications of his own discovery. The ideas that vault us into collective action need not have the status of truth; the primary value of the ideologies that inspire us in our political life is often not their descriptive accuracy but how they move us and the feelings they arouse.

Is this an insight we should welcome? Yes and no. Ideology, to be sure, is always volatile, and this is what makes it powerful—but also dangerous. In the 20th century, while Marxist theorists in the West were busying themselves with intricate debates over the nature of class consciousness and cultural hegemony, it was the fascists who came to understand the sobering truth that what binds the mass into a cohesive group is not reason but passion, not the language that helps us see the world as it really is but the far more atavistic language of symbolism and myth. In this way, Morina’s history of Marxism as a history of emotion may reveal rather more about the nature of political life than we care to admit.

More from The Nation

What Comes After the Apocalypse? A Q&A With Joshua Oppenheimer What Comes After the Apocalypse? A Q&A With Joshua Oppenheimer

Oppenheimer’s latest film, The End, is a Golden Age, postapocalyptic musical crying out from the depths of the earth.

The Peculiar Case of Ignatius Donnelly The Peculiar Case of Ignatius Donnelly

The Minnesota politician presents a riddle for historians. He was a beloved populist but also a crackpot conspiracist. Were his politics tainted by his strange beliefs?

The Agony of Aaron Rodgers The Agony of Aaron Rodgers

Is he the world’s most interesting athlete or is he just a washed-up crackpot?

Can You Understand Ireland Through One Family’s Terrible Secret? Can You Understand Ireland Through One Family’s Terrible Secret?

In Missing Persons, Clair Wills's intimate story of institutionalized Irish women and children, shows how a family's history and a nation’s history run in parallel.

Peter Schjeldahl’s Pleasure Principle Peter Schjeldahl’s Pleasure Principle

His art criticism fixated on the narcissism of the entire enterprise. But over six decades, his work proved that a critic could be an artist too.

How the Western Literary Canon Made the World Worse How the Western Literary Canon Made the World Worse

A talk with Dionne Brand about her recent book, Salvage, which looks at how the classic texts of Anglo-American fiction helped abet the crimes of capitalism, colonialism, and more...