The Twists and Turns of Language

Natasha Trethewey’s life in poetry and prose

Natasha Trethewey’s Life in Poetry and Prose

A work of biography, an essay on literature and memory and the South, a prose poem full of lyrical dexterity, Trethewey’s latest book is like all of her others: a master study of the self.

If, as Zora Neale Hurston once argued, racial prejudice is a loss not for her but for those who embrace it, then one has to wonder how much the United States has forfeited on account of its perennial anti-Blackness. “Sometimes, I feel discriminated against, but it does not make me angry,” Hurston wrote. “It merely astonishes me. How can any deny themselves the pleasure of my company? It’s beyond me.” Hurston’s “How It Feels to Be Colored Me” is sprinkled with wry aphorisms like this that slice through the layers of early-20th-century American racism. Riddled with anecdotes and Southern charm, it is also not only about Hurston celebrating her Blackness but turning the mirror back onto white Americans, who, she insists, miss a lot about themselves, too.

Books in review

The House of Being

Buy this bookThe art of showing Americans what they have missed and who they are—in particular by offering acute portraits of the South—sits at the center of Natasha Trethewey’s poetry and prose. Her accolades alone testify to her acumen. She is a griot, a former US poet laureate, and a Pulitzer Prize winner. But what has made her so vital to American literature is that she has cast back the image of a fragmented America to her readers not so much to affirm it as to offer a lament, much as Hurston did, for what has been lost—especially in the South.

This sense of hope and loss is fully displayed in her new book, The House of Being. Weaving together memoir and history, poetry and prose, intimate details from her life and more general observations about the South, the book is a testament to Trethewey’s command of language and her willingness to confront those difficult periods in her life that transformed her. A monologue, a work of biography, an essay on literature and memory, a prose poem full of lyrical dexterity, and a reflection on who she is in a society that has actively tried to partition people based on race, The House of Being is ultimately a study of maturation, of becoming an adult, and of how the early experiences of life can shape you for years to come.

Born in Gulfport, Mississippi, in 1966, Trethewey begins her story at the beginning—with her parents’ marriage. Her Black mother, Gwendolyn Ann Turnbough, was from Gulfport; her white father, Eric Trethewey, was from Canada. In 1967, an interracial couple, Richard and Mildred Loving, brought a Supreme Court case against Virginia’s anti-miscegenation law, hoping that their marital union could be recognized—and to the surprise of many Americans, they won. But Turnbough and Trethewey had married two years earlier, and the poem “Miscegenation,” which their daughter republishes in The House of Being, captures what was at stake:

In 1965 my parents broke two laws of Mississippi;

they went to Ohio to marry, returned to Mississippi.

Trethewey’s subsequent birth, while not illegal in its own right, also posed a provocation to the Southern social order: For if her parents’ marriage was deemed illegitimate in the eyes of the State of Mississippi, so was young Natasha. White people in Mississippi would stare at her parents with detestation, and some would call her “mongrel” and “half-breed.” To overcome their animosity, young Trethewey turned to literature: “I learned then from the experience of Odysseus… that it would take cleverness to outpace whatever obstacles stood before me.” The twists and turns of language captivated her. The sinewy words of her mother and grandmother speaking African American vernacular sparked an unending interest in how humans express themselves. At the same time, she thought she could see how society’s racial hierarchies mapped onto the languages spoken around her.

Trethewey’s first home was an intergenerational amalgamation that included her parents and grandmother. Slightly outside Gulfport’s city limits, the family house was in a community once known as Griswold, land settled by formerly enslaved African Americans after the Civil War. It was in this vicinity that Trethewey and her parents were exposed to the fungibility of a semi-rural landscape: red-wing blackbirds soaring through the sky, cows grazing near her backyard, or even the “cracked shell on an old turtle.”

After her parents divorced, Natasha and her mother moved to Atlanta so that her mother could begin graduate school. While her memories of her father during these years were idyllic, those of her stepfather were different. He physically abused her mother, which Natasha only found out about years later—but even then, she sensed something was wrong, and in the years to come she would be haunted by it. As she writes in her poem “What Is Evidence,”

Not the fleeting bruises she’d cover

with make-up, a dark patch as if imprint

of a scope she’d pressed her eye too close to,

looking for a way out

The worst, however, was still to come: In 1985, her stepfather murdered her mother. These moments of sorrow reappear and add to her unrelenting desire to write about her past.

From these early experiences in a South slowly shedding its Jim Crow past, the young Trethewey became an adult—and a writer. She not only understood “the sanctity of books” but felt at home through the concealments of metaphor and the ambiguities of language. In other words, she also became a poet.

Trethewey studied English literature at the University of Georgia and earned an MFA at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst. While her educational course might sound conventional for a contemporary writer, as one probes deeper into her story in The House of Being, one begins to see how unusual her literary education was. Along with her early exposure to her mother and grandmother’s way of speaking, she also had a poet in the family: her father. As a child, Trethewey recalls, her father would read stories to her that “must have taken root in my psyche, establishing early on the pattern to which my own journey would conform.”

The experiences of her mother in the South also contributed to Trethewey’s interest in writing and her skills as a poet. Her mother, she recalls in The House of Being, was always “showing me how to signify, how to use received forms to challenge the dominant cultural narrative of our native geography.”

Flannery O’Connor once wrote: “Where you came from is gone. Where you thought you were going to never was there. And where you are is no good unless you can get away from it.” For Trethewey, the dislocation of her early years led her to find a home in the written word. Poetry became a way to create regions for herself; it was also a way to examine the cyclical anguish, the loss, the trauma, and the hopes of living in a region and a country more generally that was legally and then structurally defined by the experience of race.

Over the years, Trethewey became a memoirist and poet determined to render meaning out of these facts of her life. In her collection Thrall, she probed the afterlife of captivity. In Native Guard, she mourned her mother’s death and considered the Southern world they shared. Lines in her poetry tend to jostle between life and history, relationships and regions, the experience of race and the making of it. The death of her mother would in particular come to haunt her, and she turned to prose to make sense of that, as well. In Memorial Drive, her 2020 memoir, she told the story of her mother’s life and death. A study of her relationship with her mother, the book was also a study of her mother’s relationships, of the moments of domestic bliss and the harrowing ones of domestic violence—about race-making in America and how Black women become vulnerable to abuse. “If I was with my father, I measured the polite responses from white people, the way they addressed him as ‘Sir’ or ‘Mister.’ Whereas my mother would be called ‘Gal,’ never ‘Miss’ or ‘Ma’am,’ as I had been taught was proper.” The polarizing experiences of her parents were part of an accruement of observations about the linguistic practice of racial identity—how people are read or made.

In The House of Being, Trethewey revisits many of these early memories, but from a different angle: She is primarily interested in telling the story of her native region, the South. “The ‘Solid South,’” she writes, “was a society based on the myths of innate racial difference, a hierarchy based on notions of supremacy, the language used to articulate that thinking was rooted in the unique experience of white southerners.” As with her mother’s story, so, too, with the story of the South: It has haunted her ever since she was a young person pushing against the Confederate realities and fictions that persisted in the region—whether through Jim Crow laws or groups like the Daughters of the Confederacy or the monuments memorializing the glory of Southern Civil War generals.

In The House of Being, Trethewey seeks to break through these myths and tell a different story about the South. “I am reminded again of the moment in Black Boy when Richard Wright declares he wants to be a writer,” she writes, “and what it means to have someone with a kind of dominion over you try to diminish you by telling you what you cannot do or be.” Like Wright, and much like Hurston before him, Trethewey wants to show what has been lost by telling only one story about the South, and what might be gained by telling another.

Trethewey does this in several bold and original ways. Literalizing her interest in her home region, she considers how the design of Southern homes was influenced by African and Afro-Caribbean architecture. Her grandmother’s shotgun house conveys a story not just about the period it was made in, but also a much longer history. “The long-house format,” she notes, “is a legacy of West African architecture, brought to America by both free and enslaved peoples who arrived in New Orleans from Haiti, after the Revolution in 1804.”

Trethewey also describes the darker side of the American South during the height of the civil rights movement. One of her first memories of “domestic terrorism” occurred at a young age, well before she congealed every incident that happened during the 1960s. After the African American church adjacent to her grandmother’s house led a voter registration drive in Gulfport, an unknown person (most likely white) burned a cross on the plot of land that bordered the church and her grandmother’s house. This racially coded act of hatred was frightening and had a clear message in terms of the violence it conveyed, but it was also ambiguous: It left Trethewey retroactively wondering whether it was motivated by the voter drive or by her interracial household. Such ghosts stalk The House of Being, rambling through its corridors and stairways. Memories, Trethewey reminds us, raise questions that do not always have answers. The South is a place that is simultaneously welcoming and inimical, a home to millions and yet also a hostile land.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →At times, I wondered if The House of Being needed a more cohesive narrative arc—a clear beginning, middle, and end. The text is often elliptical, circling back on memories and skipping ahead to new and unfamiliar territory. Often it invokes previous books and poems that Trethewey has written, as well as pasts that some of us may need to be more familiar with. This can be invigorating but also frustrating. Yet for Trethewey, the labyrinthine nature of the book is intended to match form with content: Her desire is not to offer a clean and linear narrative. Instead, she wants to tell a story about the South that is full of messiness and confusion. “Writing,” Trethewey notes near the end of the book, “is a way of creating order out of chaos, of taking charge of one’s own story, being the sovereign of the self by pushing back against received knowledge and guarding the sanctity of the dwelling place of the imagination.”

More from The Nation

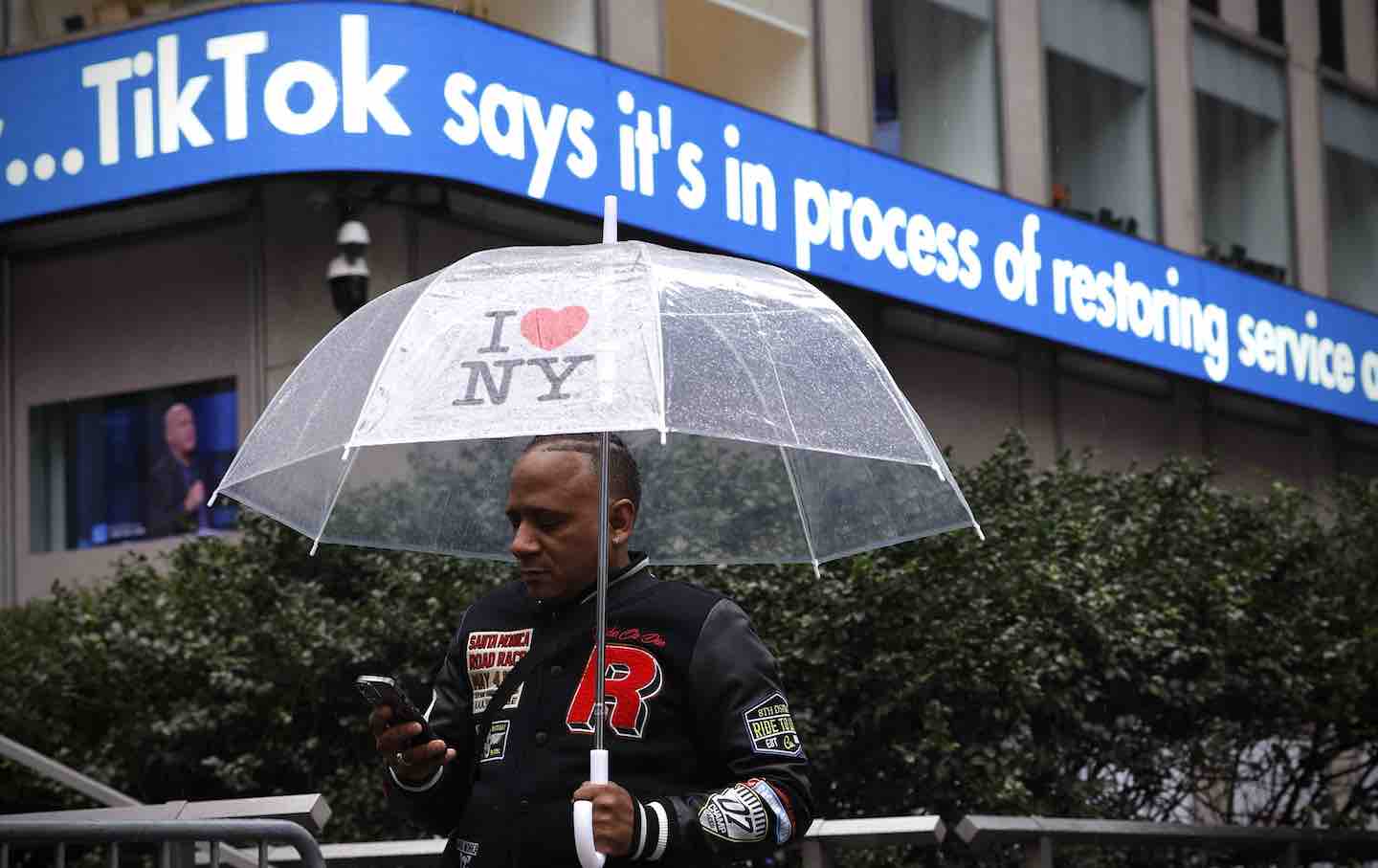

TikTok’s Incomplete Story TikTok’s Incomplete Story

The company has transformed the very nature of social media, and in the process it has mutated as well—from tech unicorn to geopolitical chesspiece.

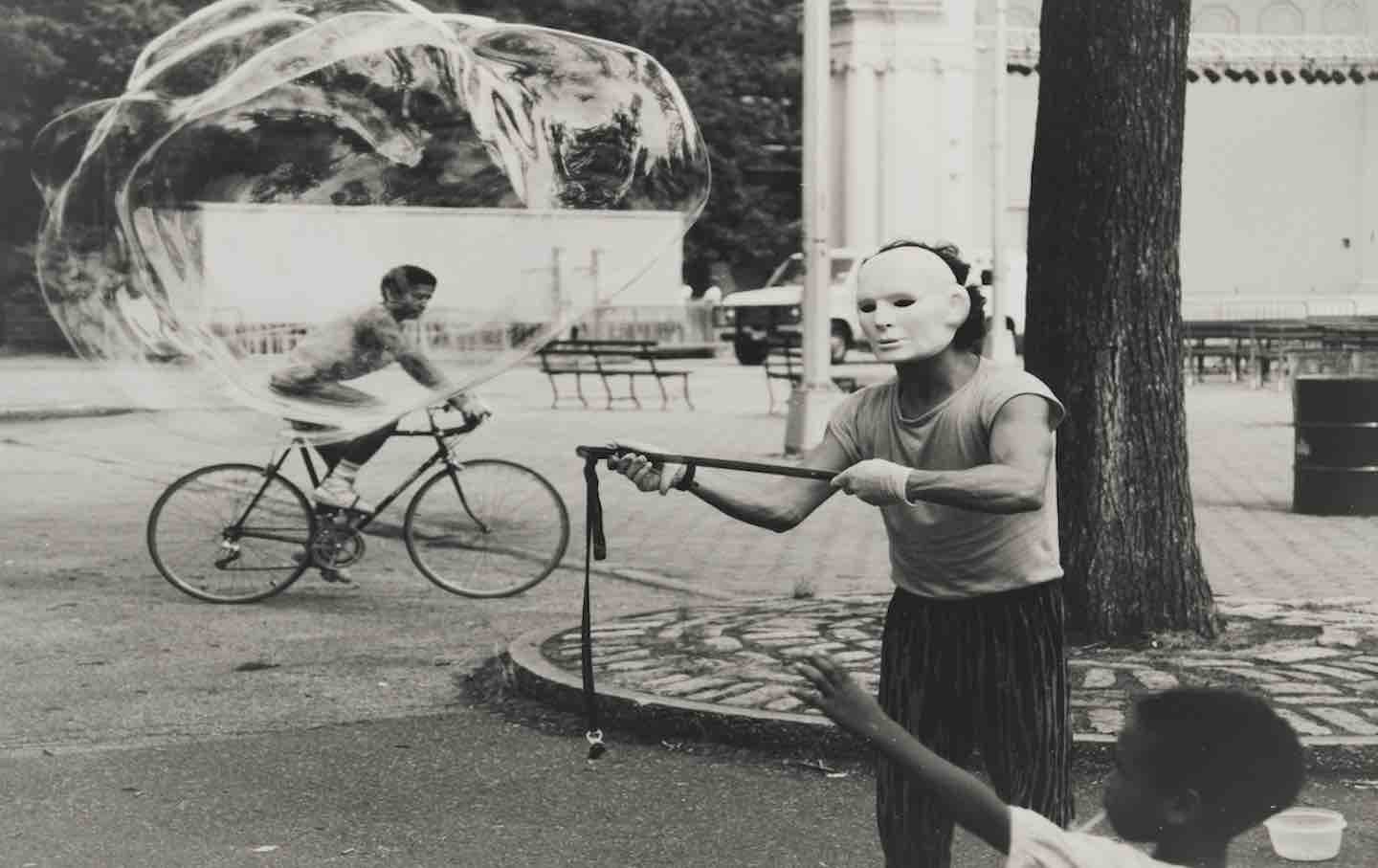

Did We Get the History of Modern American Art Wrong? Did We Get the History of Modern American Art Wrong?

The standard story of 1960s arts is one of Abstract Expressionism leading into Pop Art and minimalism. A Whitney show proposes an altogether different one centered on surrealism.

The Bleak History of the American Work Ethic The Bleak History of the American Work Ethic

In Make Your Own Job, Erik Baker shows just how long Americans have scrambled to pile work on top of work—and at what cost.

The Banal Spectacle of “Avatar: Fire and Ash” The Banal Spectacle of “Avatar: Fire and Ash”

Has James Cameron’s epic sci-fi series run aground?

The Dislocations of Shuang Xuetao The Dislocations of Shuang Xuetao

The Chinese writer’s fiction details how the country transformed on an intimate level after the Cultural Revolution.

An Absurdist Novel That Tries to Make Sense of the Ukraine War An Absurdist Novel That Tries to Make Sense of the Ukraine War

Maria Reva’s Endling is at once a postmodern caper and an autobiographical work that explores how ordinary people navigate a catastrophe.