Back to Earth

The return of Kid Cudi.

The Many Evolutions of Kid Cudi

In Insano, the rapper and hip-hop artist comes back down to earth.

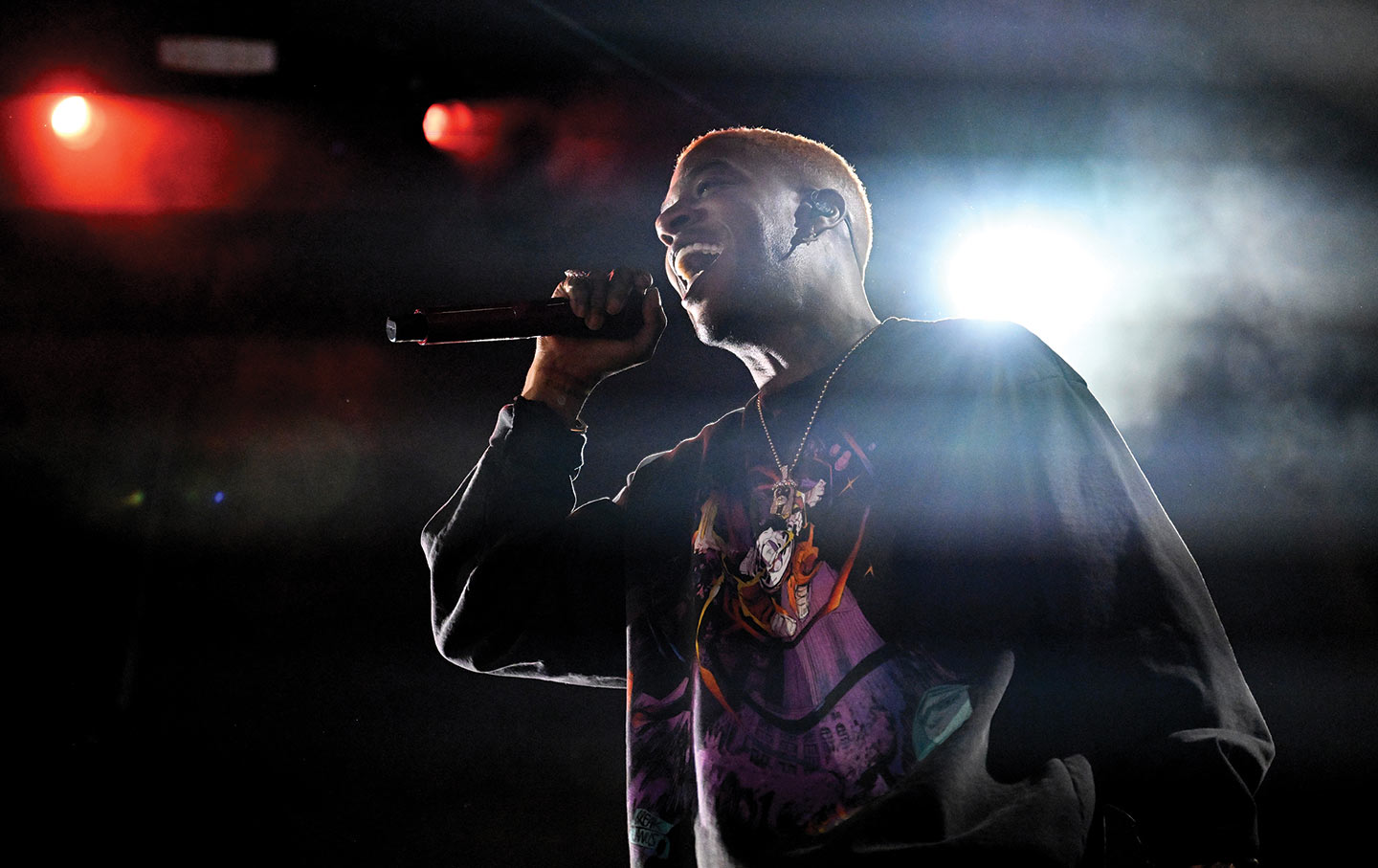

Kid Cudi in Las Vegas, 2024.

(Photo by David Becker / Getty)Kid Cudi has returned from space with Insano, his ninth studio album. It’s a decidedly material effort, one that’s more about the party than it is about the comedown. Cudi is no longer on the moon; he’s planted his feet right here on Earth.

On the album, Cudi has brought along a few guests who like to party—Travis Scott, Young Thug, Lil Wayne—and the whole romp is narrated by DJ Drama, whose main job is scene-setting. It feels like a capital-T traditional 2020s rap album, with slick 808s and heavy kicks running throughout. But there’s something weighing Insano down too, something that keeps it from reaching escape velocity. There’s a listlessness—even a boredom—in the midst of all this partying. The boasts feel rote, the occasional introspections a little fake-deep. Cudi and his friends are having a party, but is it fun? Is it really? Insano is, for better or worse, just fine. It’s neither ambitious nor groundbreaking; it sounds like content.

When you talk about Kid Cudi, it is hard to escape mentioning Man on the Moon: The End of Day, his first studio album. That’s mostly because it was both an era-defining and an artist-defining album.

The production was melodic, but spare enough to let Cudi’s unvarnished tenor take center stage. The beats were deceptively simple, built with lots of synths on top of simple syncopated drums. His id was on display, too; The End of Day was an autobiographical concept album. The narrative was simple but profound: We were journeying through the artist’s mind, going from struggle to success. Telling the story of its hero, the album often felt like a heady stoner epic birthed into a world of gangster rap. If you were a moody teenager or an emo twentysomething when it was released, The End of Day was an event: It was finally something different.

Since then, Cudi has continued to evolve as an artist. He started side projects with Travis Scott and Kanye West, a rock band called WZRD, and released an alternative-rock album that featured Beavis and Butt-head skits from Mike Judge. He did two sequels to Man on the Moon and a few other rap albums to boot, including Passion, Pain, & Demon Slayin’ and Indicud. He also began a thriving career as an actor, with roles in films like Entourage and Bill & Ted Face the Music, as well as on television, where he recently produced an Emmy Award–winning animated miniseries for Netflix called Entergalactic, with an accompanying album. He just released a comic book that instantly sold out, along with an accompanying song featuring Denzel Curry. One of the great pleasures of aging is watching the artists you grew up with evolve. That’s true for Cudi: His path through fame has been fairly satisfying.

Yet considering the variety of Cudi’s career as a musician, Insano feels a little disappointing. The experimentation is mostly limited to the song “Electrowave Baby,” a bop that samples Ace of Base’s smash hit “All That She Wants.” It’s a genuinely good song that nevertheless doesn’t sound like it belongs on this album—but that’s because the rest of Insano has a sameness to it that’s almost soporific.

Some tracks end up a bit ponderous, like “Tortured,” which feels like a readout of all the things Cudi does to cope. It opens strong, with a 2024 version of Jesus’ lament in Gethsemane: “God, help me (Ooh-ooh), God, help me (Ooh-ooh), please (Ooh-ooh-ooh) / Do you hear me? (Ooh-ooh-ooh, ooh, ooh-ooh-ooh) Do you hear me?” But then Cudi seems to lose the plot. The next words out of his mouth are “In the dark (Yeah), in the trippy night / I wish the Devil would fuck off (Fuck ‘em).”

Lyrically, it’s as if you added salt to a recipe that called for sugar. The rest of the song is weighed down by Cudi’s singing, which feels oddly leaden and overproduced. And then we get this bar: “What’s the cause? (Yeah) Tryna find my way inside this bitch, this shit is hopeless / Counting down the minutes, playin’ tennis with emotions (Yeah) / Tryin’ different therapists, they sayin’ I got problems.” It’s all over the place, emotionally speaking. And it’s not an isolated case; this kind of tonal whiplash is all over the album.

It even happens on the more successful introspective songs, like “X & Cud.” It’s a duet with the rapper XXXTentacion, who died in 2018, and samples his 2017 song “Orlando.” Cudi adds a beat and cleans up the vocals, which doesn’t detract from how haunting the song is. In Cudi’s version, we get a first verse from him that only adds to the spectral quality:

Mind is the maze thinkin’ ‘bout what I can’t change

Devil’s on my head and I don’t want to worry my friends

They told me, “Say somethin’,” don’t think they’d understand.

Momma truly gets when my daddy left, the wound, it ain’t mend

But then something feels off again. Cudi’s second verse devolves into braggadocio, slipping from the mournful to the brash: “Will he cower? Never, ever, Cleveland City / Born a grinder, watch him ripping, can’t stop him / Came in filthy, double O’a, reppin’ for ‘em.” And it feels tonally wrong, given that it’s coming immediately after XXXTentacion sings, “So nobody wants death ‘cause nobody wants life to end / I’m the only one stressed and the only one tired of havin’ fake friends / Faced my fears, can’t keep love at all.”

“Orlando” was a lament in the traditional sense, just three chords on a piano and X’s voice. It was about his loneliness; it was about waiting for death, and regretting the waste and worthlessness of a life—his life. It is genuinely beautiful, born out of genuinely strong emotions. So when Cudi pivots into a different tone, it feels jarring.

Other songs on Insano miss the mark in similar ways. In “Cud Life,” we go on a trip to “rager town” and get this awkward line: “Ain’t had the best luck (luck) / Nigga in the struggle like ‘Fuck’ (fuck).” In the struggle like “fuck?” I mean, sure, that’s one way to put it.

All that said, some songs work a lot better, tonally speaking. And those, not coincidentally, are the ones where it sounds like everyone’s having fun—for example, “Porsche Topless,” which is about celebrating your own success in a fast car. When Cudi sings “Feelin’ right, feelin’ perfect, mm-hmm (Yah) / Surfin’, got my wave, cowabunga, ooh-wee (Yeah),” I get it; I’m there. Because who hasn’t felt that way, on a perfect night with the perfect people to share it with? Same goes for “Freshie,” which is an ode to potency, to feeling like you’re in control. The world’s his, or at least it feels like it is: “I’m just a king livin’ dreams come true (Ah) / I’m winnin’ and I been in it, make her cream, don’t gotta say I wanna (Ah).”

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →And here, as with just about every other song on the album, the production is fantastic. The surfaces sparkle; it just sounds good. This is absolutely an album to play as loud as you can, I think. So long as you don’t listen too closely to what’s being said.

All of this is not to say that Insano is bad. In fact, many of its songs are pretty good, and maybe that’s the worst thing about it. It has a few great tracks—“Electrowave Baby,” “Mr. Coola,” “Freshie,” “Porsche Topless”—and many mediocre ones. It’s a bit too long, and I’m not sure the narrative window dressing (though a Cudi staple) really does a lot here. It’s an album for the already converted, the ragers in rager town.

But that makes it feel like Cudi’s resting on his laurels, and given his career at this stage, I can’t begrudge him that. I hope, on his next album, we get more experimental work—something that sounds as different now as The End of Day did then. Insano is an album that reminds you of what it’s like to be back on Earth. But I’d love to hear Kid Cudi somewhere new. Maybe the sea? He’s one of the few artists I’d trust to bring us there.

More from The Nation

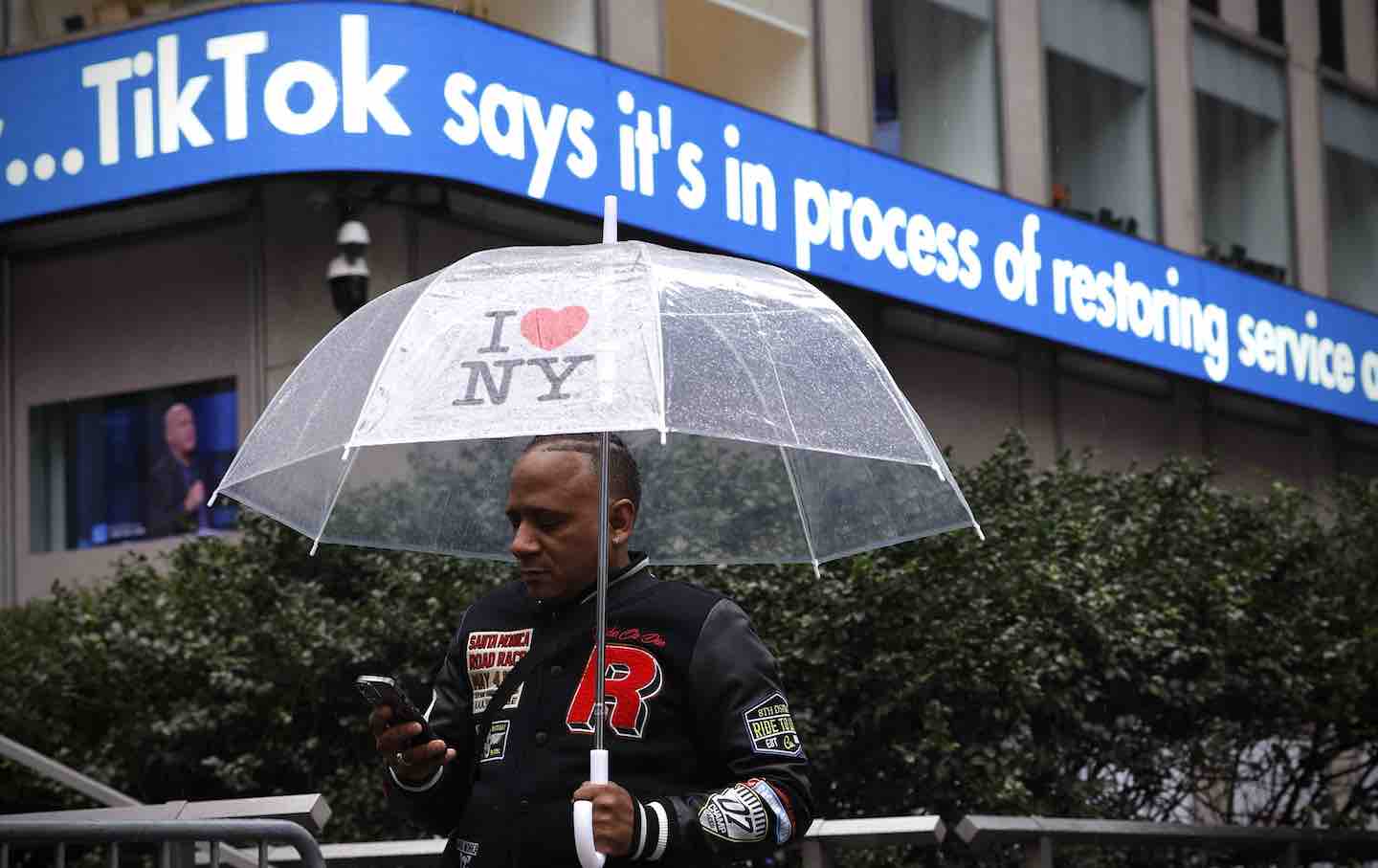

TikTok’s Incomplete Story TikTok’s Incomplete Story

The company has transformed the very nature of social media, and in the process it has mutated as well—from tech unicorn to geopolitical chesspiece.

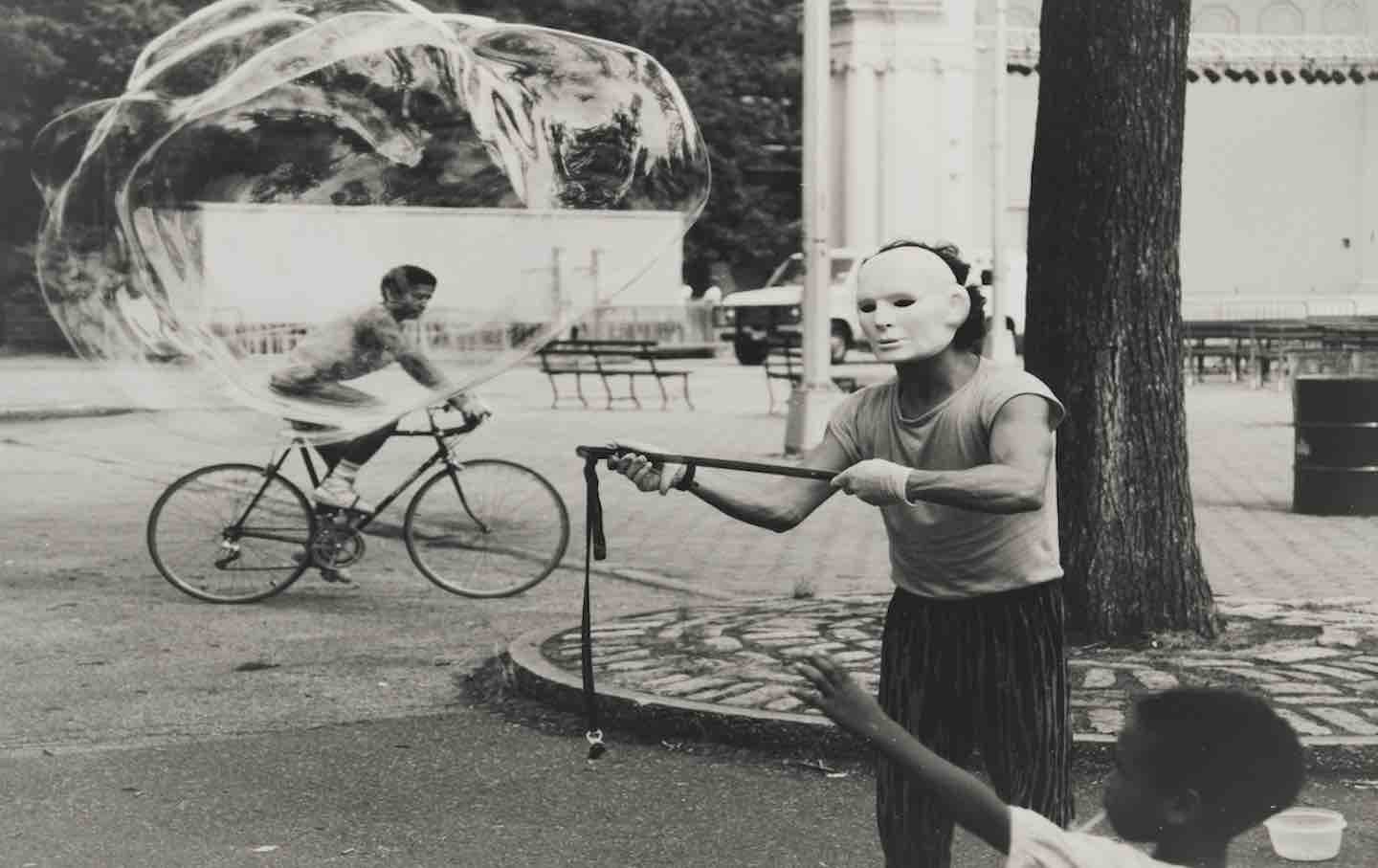

Did We Get the History of Modern American Art Wrong? Did We Get the History of Modern American Art Wrong?

The standard story of 1960s arts is one of Abstract Expressionism leading into Pop Art and minimalism. A Whitney show proposes an altogether different one centered on surrealism.

The Bleak History of the American Work Ethic The Bleak History of the American Work Ethic

In Make Your Own Job, Erik Baker shows just how long Americans have scrambled to pile work on top of work—and at what cost.

The Banal Spectacle of “Avatar: Fire and Ash” The Banal Spectacle of “Avatar: Fire and Ash”

Has James Cameron’s epic sci-fi series run aground?

The Dislocations of Shuang Xuetao The Dislocations of Shuang Xuetao

The Chinese writer’s fiction details how the country transformed on an intimate level after the Cultural Revolution.

An Absurdist Novel That Tries to Make Sense of the Ukraine War An Absurdist Novel That Tries to Make Sense of the Ukraine War

Maria Reva’s Endling is at once a postmodern caper and an autobiographical work that explores how ordinary people navigate a catastrophe.