The Crime Scene

Jafar Panahi’s dissident films.

Jafar Panahi’s Scenes From a Crime

His films show how a regime’s wrongdoing can upend one’s sense of self and transform the very rhythm of daily life.

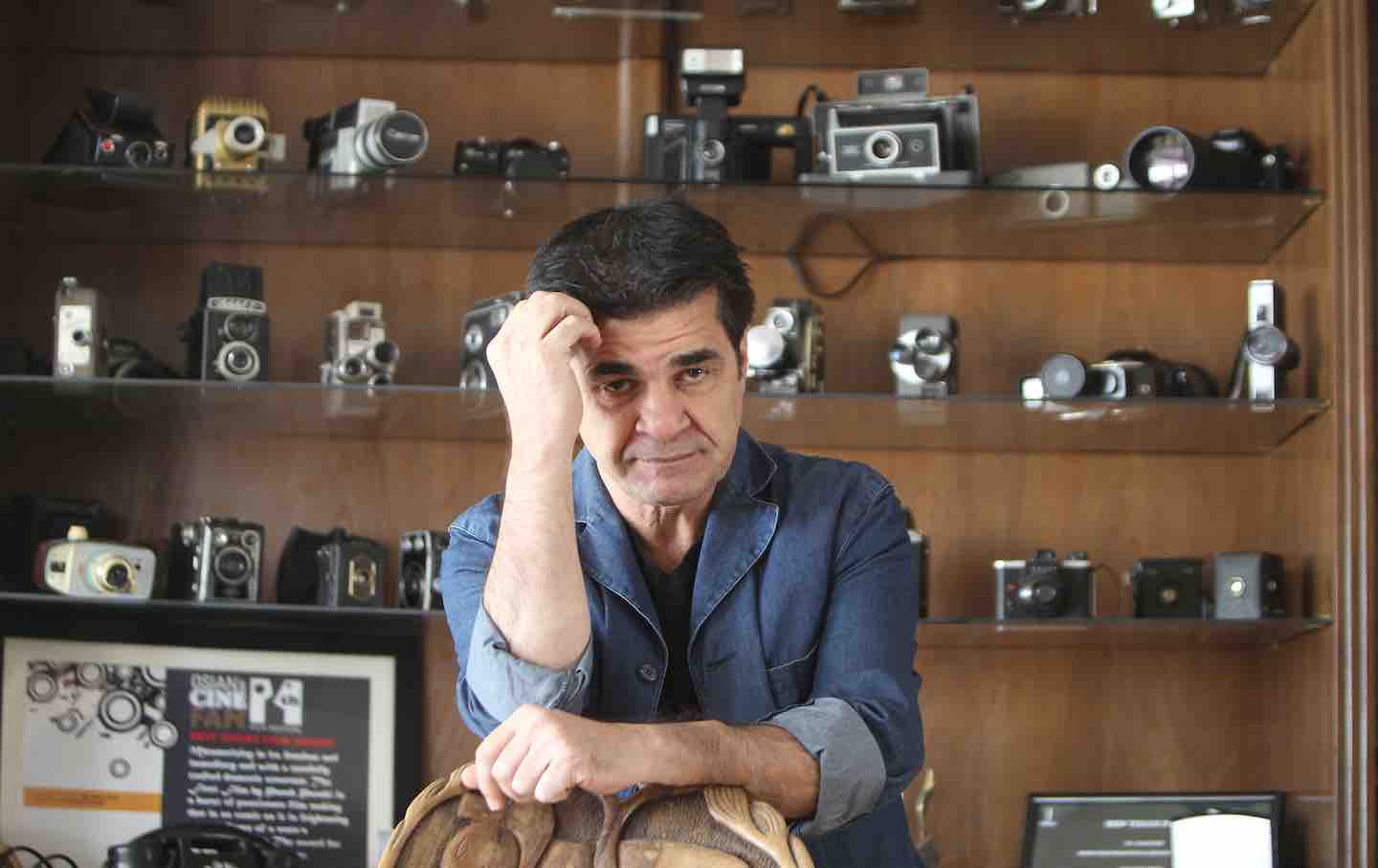

Jafar Panahi, 2010.

(Photo by ATTA KENARE/AFP via Getty Images)

The photographs of Eugène Atget document the ghostly residues of a Paris on the verge of disappearance. Typically devoid of people or other signs of life, Atget’s images capture desolate and seemingly unremarkable urban locations—an empty street, an enigmatic building—that seem pregnant with some kind of meaning, but obstinately refuse to disclose it. These were locations that would soon be wiped out by the urban modernization of the city initiated by Georges-Eugène Haussmann, which replaced sections of old Paris with wide boulevards. Walter Benjamin remarked that Atget photographed these streets “like scenes of crime. The scene of a crime, too, is deserted; it is photographed for the purpose of establishing evidence.” Evidence of what? Atget’s photography insistently courts this question, even as it declines to answer.

In Jafar Panahi’s most recent film, It Was Just an Accident, a city’s seemingly banal locales are similarly reframed as sites of some terribly important yet elusive meaning. But here, what invests the quotidian with portending significance is sound. On the outskirts of Tehran, a car mechanic opens up his garage late at night for a stranded traveler whose car has broken down. As the traveler walks around, the squeak of his prosthetic leg becomes audible. The mechanic looks shaken, and the next day, he follows the man into the city, where he kidnaps him and drives him out to a remote stretch of desert. As the mechanic, Vahid, starts digging a grave, he accuses the man of torturing him when he was imprisoned for his labor activism years ago, leaving him with a permanent limp. And the proof of his identity, Vahid claims, is the unmistakable sound of the squeaking prosthetic limb that belonged to the torturer, whom the prisoners called Peg Leg.

Begging for his life as Vahid piles dirt on top of him, the man denies being Peg Leg, and Vahid decides that he can’t go through with it without being sure. So he locks the man in a box in the trunk of his van and drives into Tehran in search of other prisoners who might be able to verify the man’s identity. As the film embarks on this tour of the city, Tehran’s banal settings take on an ominous air. In the same manner as Atget’s photographs, the street corners and parking lots hold their tongue as Vahid sets off on a kind of detective story, trying to piece together evidence of the regime’s crimes.

As perhaps the Iranian film industry’s most high-profile dissident, Panahi himself is no stranger to being victimized by his government. Since the release of his third feature film, The Circle (2000), which portrayed the misogyny of Iranian society, Panahi’s films have been banned by the government, and he has officially been prohibited from directing. A government official castigated The Circle for its “completely dark and humiliating perspective” on Iran, but Panahi continued to make politically critical films despite increasing pressure from the government. He was later imprisoned for several months in 2010 and then, after a hunger strike, placed under house arrest; in 2023, he was imprisoned again after protesting the sentence of his fellow director Mohammad Rasoulof. (He was released after another hunger strike.)

Panahi defied the attempts to silence him by making films in secret throughout this time. It Was Just an Accident is no exception: Although it uses many bustling streets in Tehran as backdrops, it was made illegally, without approval from the government. It has gone on to garner widespread international acclaim, winning the Palme d’Or at the Cannes Film Festival—which only seems to have aggravated the Iranian government’s persecution of Panahi. In December, while traveling in the United States to promote the film, Panahi was sentenced in absentia to one year in prison and a two-year ban from leaving Iran. Although he remains free while abroad, he has vowed to return to Iran and face the charges, despite the protests that recently convulsed the country and threatened to topple the Islamic Republic. At the end of January, one of Panahi’s co-screenwriters on It Was Just an Accident, Mehdi Mahmoudian, was arrested after he signed a statement condemning the regime’s killing of protestors. Panahi signed the statement too. “I am the kind of person who needs to be in his country,” Panahi said when asked if the unrest had changed his resolve to return. “I need to breathe there and work there. And even if they want to go ahead with that prison sentence, they can go ahead. Nothing will change my mind about going back.”

Panahi began his career as an assistant director for the renowned Abbas Kiarostami, whose contemplative films gently blurred the boundary between documentary and fiction. In 1994’s Through the Olive Trees, Panahi makes an appearance in his capacity as assistant director. It’s not difficult to see what Panahi learned from Kiarostami’s work, since he too would go on to explore the affordances of metafiction. Both directors also began their careers by making movies about children. Panahi’s 1995 debut, The White Balloon (which was scripted by Kiarostami), centers on a young girl whose attempt to buy a goldfish is frustrated when she accidentally drops her money down a grate.

His second film, The Mirror (1997), begins on a similar note of children running up against the indifference of the adult world. Its opening section begins unassumingly, following a schoolgirl named Mina as she tries to find her way home from school after her mother doesn’t come to pick her up. Swaddled in an arm cast, Mina navigates the chaotic streets of Tehran, eventually making her way onto a bus. Sitting next to the conductor, she glowers with annoyance. Suddenly, a voice calls out: “Mina, don’t look at the camera.” This is the voice of Panahi himself, interrupting the film to instruct the child actor on what to do. This doesn’t go over well—Mina’s annoyance wasn’t an act, and Panahi’s pushiness is the last straw. “I’m not acting anymore!” she angrily declares, before demanding that the bus stop to let her out. From here, the film switches into a documentary mode—but perhaps the strangest thing about this is that nothing much seems to change. Although Mina discards her prop cast, she continues trying to find her way home, running through the streets of Tehran just as she did before. What seemed like a straightforward flip from fiction to reality actually muddles the dichotomy between the two.

What sets Panahi apart from Kiarostami is a much sharper edge of social critique. Along with his ambitious metafictions, he has also made works of gritty social realism, unsparing in their representation of Iran’s inequities. Shot illegally in the depths of Tehran and explicitly channeling Italian neorealism, these films exposed the desperate conditions afflicting vulnerable segments of Iranian society and were particularly concerned with the plight of women. Offside (2006) is about a group of girls who disguise themselves as men to sneak into a soccer stadium for a big match, and it inspired a feminist movement that began protesting soccer matches with signs referring to the film; Crimson Gold (2003) centers on a pizza-delivery driver who is spurred to violence by the indignities of monstrous inequality.

Throughout this time, Panahi had been periodically arrested or questioned for various infractions, but in 2010, the government ran out of patience and convicted him of propaganda against the Islamic Republic and crimes against national security. He was sentenced to six years in prison and a 20-year ban on making films. Although he ended up under house arrest rather than serving the full prison sentence, the filmmaking ban remained in place until 2023, forcing him to shoot his intervening five films in secret. In them, Panahi plays a thinly fictionalized version of himself, which was probably born out of necessity since these films were made clandestinely and on the fly. The first of these works, This Is Not a Film (2011), follows Panahi as he languishes in his apartment during his house arrest, dealing with banal problems like a neighbor who wants him to watch her dog while also fielding calls from his lawyer about his legal proceedings. A title card informs us that the film had to be smuggled out of Iran on a flash drive hidden in a birthday cake. After this, Panahi continues to appear in the films but is able to venture out somewhat more into the open. Taxi Tehran (2015) finds him driving a cab around the city and interacting with colorful passengers, although it alludes in a number of ways to the repression lurking just out of frame. It Was Just an Accident is his first film since the ban was lifted, and it appears to mark a break from the autofictional. Panahi has attributed the change in direction to the newfound freedom of his working conditions: “At least psychologically, I didn’t feel I was still under the ban; I wasn’t obsessed with myself, or with my old situation. I was able to open up, and to dedicate my work, my film, to the people I had spent time with in prison.” But does it have more in common with Panahi’s previous work than it first appears?

It Was Just an Accident begins inside the tight quarters of a small car, taking us into the cramped intimacy of a small family of three on a nighttime drive. An unassuming man, his wife, and their young daughter drive on a rural road late at night and accidentally hit a dog. As the man gets out to inspect the damage, a strange creaking echoes through the eerie silence with each step he takes. But once he arrives at the garage and triggers the mechanic’s suspicions, the narrative shifts its focus entirely, instead coming to foreground Vahid and his fixation on uncovering whether the man is Peg Leg. This switch in identification—initially encouraging the viewer to see things through the eyes of the driver, only to then transplant us into Vahid’s perspective—is just the kind of disorienting maneuver that Panahi relishes. Knocking the viewer off-balance, upsetting our assumptions about where to invest our attention, injects a current of suspicion into everything that follows.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →The origins of this move can be found in Panahi’s intrusion into The Mirror, the tremors of which continue to reverberate through the rest of his work. Unsettling our perception of what belongs to the film’s diegesis and what doesn’t startles the viewer into a heightened state of awareness, like the one that takes hold after missing a step on the stairs. And in his later work—in the films made under the ban—Panahi continues to play with the viewer’s sense of what counts as stable ground. In the first scene of No Bears (2022), we watch a man and a woman have an intense conversation about the fake passports they need to escape the country. The man, Bakhtiar, has managed to obtain one for the woman, Zara, but not for himself. He tries to convince her to go without him, telling her that he will follow when he can, but she refuses. As Bakhtiar dejectedly retreats, somebody shouts “Cut!” The camera then zooms out to reveal that the events we have been watching were taking place on a laptop screen; they were staged as part of a film.

Why does Panahi insist on pulling the curtain back like this? What lies behind the suggestion that the cinematic worlds he constructs on-screen are ultimately a form of deception? Like No Bears, 3 Faces (2018) begins with a film within a film, one that similarly turns out not to be what it seems. A crying teenage girl films herself on a cell phone, explaining that her closed-minded family won’t allow her to attend drama school in Tehran. She’s addressing a famous actress to whom she’s sent the video, at the end of which she seemingly hangs herself. The shaken actress rushes to the rural village where the girl lived, accompanied by a director named Jafar Panahi (played, of course, by Panahi himself), where they eventually discover that the whole thing was staged as a cry for help by the desperate girl, who is in fact being stifled and prevented from pursuing acting by her oppressive family. The deception to which she had to resort starts to look like a natural response to a society twisted by prejudice.

In No Bears, too, the aperture gradually widens to take in a larger context. Bakhtiar and Zara, it turns out, aren’t acting in the conventional sense of the word; they actually are trying to get passports so they can emigrate to France, where they hope a better life awaits. Their predicament is being filmed by a director, again played by Panahi himself, who is staging things remotely to make a kind of dramatized documentary. But all of these terms—like acting, staging, or documentary—can only be understood as provisional, since No Bears is determined to radically undermine them. Bakhtiar manages to procure a passport for himself, and we watch through Panahi’s camera as it captures the scene of his departure. But Zara suddenly turns to the camera and angrily addresses Panahi through the screen, saying that she knows the truth: Bakhtiar’s passport is fake, part of a ploy to trick her into leaving the country without him. It’s hard to keep track of the intricate and multilayered deceptions being perpetrated, by both the characters and the camera itself, and the result is to suspend the viewer in a haze of uncertainty. In this way, Panahi turns his filmmaking practice into an exploration of how a breach of trust irrevocably changes everything that comes in its wake, inducing an epistemic breakdown that throws what used to be reliable into question. The only thing that remains sure is what Bakhtiar sobs after Zara goes missing: “Now that I’ve lied to her, nothing will be the same again.”

Although It Was Just an Accident doesn’t engage in the same kind of metafictional destabilization, it is similarly concerned with breaches of trust and their irreversible consequences. And like 3 Faces, it draws on the detective genre, with its characters trying to get to the bottom of something that might be a heinous crime. But the crime in question turns out to be more diffuse than any discrete act, more like something being perpetrated by an entire society rotting from within.

After kidnapping the man, Vahid seeks help from a friend and is directed to a former journalist named Shiva who was once a victim of Peg Leg, too. She had been jailed for writing articles critical of the regime and is now working as a photographer. When Vahid finds her, she’s in the middle of a session, taking wedding photos. Shiva tries to send Vahid away, but the bride, Goli, hears the commotion and finds out about the man being held captive—it turns out that Goli was also tortured by Peg Leg, and she insists on coming with Vahid to find out whether it’s really him. They’ve only just managed to attain a normal life, Shiva says, but the scars of the past, once reopened, need to be closed.

None of the three are certain that the man is Peg Leg, since nobody saw his face during their imprisonment. Shiva claims that the smell of the man’s sweat is the same, but like Vahid’s claim about the sound of his prosthetic leg, this doesn’t seem to be enough to go through with killing him. Shiva says the only person who can know for certain is her ex-lover Hamid, who turns out to be erratic and angry, still stewing in resentment over the injustices committed against him. Hamid is certain that the man is Peg Leg; he was forced to feel Peg Leg’s scars while in prison, and the feel of the scars on this man’s leg is exactly the same. Returning to Panahi’s preoccupation with truth and deception, the film orbits around the testimony of the senses, asking whether the body’s knowledge of trauma is enough to convict this man of being Peg Leg. Sound, smell, and touch all attest to his identity. Is that enough to warrant his death sentence?

All of this plays out against the nondescript backdrops of Tehran. But as the group moves throughout the city, they start to attract unwelcome attention, thanks to Hamid’s growing agitation and Goli’s conspicuous wedding dress. It’s clear to the onlookers that something suspicious is going on inside Vahid’s van. And the only way to get them to look the other way is to bribe them. Random passersby are constantly soliciting cash: the nurses at a hospital, a group of street musicians, a pair of security guards who slickly whip out a portable credit-card machine for their “gift.” The atmosphere of normalized graft and pervasive suspicion is just as much a product of the regime’s repression as Vahid’s limp and the group’s many other injuries. And as Vahid and the others are pulled further into the muck of the city’s claustrophobic paranoia, this disintegrating social fabric is ultimately the deeper crime that they uncover, one that spans the whole of a broken society. Goli’s pristine wedding dress, which seemed to embody the promise of a brighter future, ends up soiled and dirty. By the film’s end, even when things appear to have come to a delicate resolution, all it takes is the sound of something squeaking—maybe a prosthetic leg, but maybe not—to shatter a hard-won peace. Like Atget’s photographs, Panahi’s vision of the city is permeated with dread: the kind that accompanies the knowledge that everywhere you look is the potential scene of a crime.

More from The Nation

Molly Crabapple's Time Capsule of Resistance Molly Crabapple's Time Capsule of Resistance

A new set of note cards by the artist and writer documents scenes of protest in the 21st century.

The Exposure Therapy of “A Private Life” The Exposure Therapy of “A Private Life”

In her new film, Jodie Foster transforms into a therapist-detective.

Letters From the March 2026 Issue Letters From the March 2026 Issue

Basement books… Kate Wagner replies… Reading Pirandello (online only)… Gus O’Connor replies…

How to Build a Moon Garden When the News Is All Horror How to Build a Moon Garden When the News Is All Horror

The Riotous Worlds of Thomas Pynchon The Riotous Worlds of Thomas Pynchon

From “The Crying Lot of 49” to his latest noirs, the American novelist has always proceeded along a track strangely parallel to our own.