Diane Oliver’s Fiction From Both Sides of the Color Line

Neighbors and Other Stories, a posthumously released collection, looks at all the uncertainty and promise of coming of age during and after the civil rights era.

Washington, DC, street corner, 7th Street and Florida Avenue N.W.

(Photo by Heritage Art / Heritage Images/via Getty Images)

How do you make art about racism?

Didacticism—the injunction that writers of color protest and argue their full humanity—has always been one approach, but not the most satisfying. Prejudice (enduring it, staging it) is not often one of the central dilemmas of great literature, because it is so obvious, and obviously abominable, that it might be an enemy of aesthetic complexity and affective power. (Might.) Toni Morrison wrote only about Black people, and thus depicted the effects a racist and colonial history had on them, but actual white people and their direct, unvarnished hatred were typically quite absent from her fiction. Morrison called racism a “distraction” from her work; it couldn’t be the main character. A few Black writers, like Percival Everett or Marie NDiaye, prefer subjects other than race, or else write about it abstractly while refusing the simple directive of representation.

Books in review

Neighbors and Other Stories

Buy this bookDiane Oliver, a 22-year-old writer who died in 1966 in a motorcycle accident, had been working out an idiosyncratic answer to this question that lies at the heart of Black fiction. At the time of her death, Oliver was a student at the Iowa Writers Workshop, one of only two Black attendees at the time. (The now-acclaimed novelist John Edgar Wideman was the other.) She had published four stories—one of which won a posthumous O. Henry Award—and passed through the same Mademoiselle internship that produced Sylvia Plath and Joan Didion. Only now, with Grove’s publication of Neighbors and Other Stories, has the loss of such a promising talent truly come to light.

Neighbors, then, is that troublesome artifact: an artist’s unfinished work, assembled posthumously by an admiring editor as best as one can without the writer’s guidance or approval. Oliver’s collected works show quite a range of tone, subject, and setting. They portray the absurdity and frustrations of poor and middle-class Blacks alike; two stories even observe the interior life of mid-century whiteness in flux. College, Chicago, the Swiss Alps, numerous nameless Southern towns: Oliver’s characters try to make a home in each, except that true belonging is neither easily won nor maintained, and can elude a person even in familiar climes.

What unites such disparate stories are the deeply American modes of narration to which Oliver returns time and time again: They explore the manifold ways that thrift, industriousness, and idealism can fail in such an individualistic culture as our own. Our well-intentioned deeds and values might fail to pay the bills, but they might also fail to make us content, or into something better than we were before. This failure, which remains a possibility for almost everyone in the country, is nonetheless more familiar to people of fewer means or darker complexions, and Oliver’s dramas of race and class probe the failure from a somewhat neglected vantage in mid-20th-century American fiction. By this I mean not Oliver’s race but her book’s historicity: Her coming of age coincided with the heyday of the civil rights era, and one of the great gifts of this collection is its textured fictionalization of the period’s upheaval and uncertainty.

Oliver herself was a member of the unusual milieu that was the Jim Crow South’s Black middle class. Her parents were educated, one a schoolteacher and the other a piano instructor, and Oliver was clearly a precocious student. Without a doubt, some of her experiences as a “first” or an “only one” live in these stories. We are glad, in hindsight, of equality under the law, but what is the price of the ticket to an integrated society? The photonegative of racial progress might have been a mandate to mix where none had yet existed. Hostility and strange looks loomed in the distance. The Little Rock Nine were traumatized by integrating their new school.

For Oliver, legal integration did not cure the vertigo of encountering the Other, an Other most Black people had never publicly dined with or gone to school alongside. Of course, all fiction concerns this encounter, and in this sense racism is just one of its manifestations. Oliver saw no reason why it couldn’t be the fount of an art both complex and truthful.

The titular story in Neighbors is a master class in suspense: A boy of about 7 prepares to be the first to integrate the local elementary school, but we don’t meet the child until the story’s midpoint. Instead, the shape of the very telling shows how a boy with little agency becomes a projection of everyone else’s fears and hopes—especially those of his loving family. Tommy doesn’t even know how much rests on his tiny shoulders; he simply wants to enjoy his bright and colorful books. Winifred, from “The Closet on the Top Floor,” is herself the picture of reluctance as she matriculates to a heretofore all-white college. Between Tommy and Winifred, we see how integration as an ideal did not account for Black people’s well-being after civil rights were granted. Tommy’s fate is left unclear, but history is suggestive; Winifred, on the other hand, undergoes a sort of self-sabotage and is unable to complete the term.

Indeed, if the story of American progress or racial triumphalism is a comforting aspiration, it is not a moving or even realistic premise in fiction: Instead, Oliver’s twisty narratives want to capture advancement’s more ambiguous emotional terrain. How many wealthy, famous, or otherwise well-positioned people have noted the irony with which their privileges become burdens? In Oliver’s fiction, disappointment courts any number of characters, often women, who attempt to improve their station. Alice, in “The Visitor,” is a fretful, light-skinned woman, born poor, who marries the only colored doctor in town but has to contend with both his indifference and that of his daughter from a previous marriage. Alice’s foibles and superficiality—her relentless projection onto others of a bourgeois, ladylike fantasy—make her the collection’s funniest character.

She might be compared with the more tragic Meg in “Spiders Cry Without Tears,” a white divorcée who also marries a Black doctor, the charming Walt. (In other words, Meg must have done it for love, since she had so much to lose.) In Meg’s Southern town, miscegenation is newly legal but not yet socially sanctioned, and she navigates opprobria both unnamed and explicit. But her interracial relationship is not necessarily depicted as a cause for celebration, nor does Meg strike us as particularly brave or political: The implication remains that, like so many, she married because she was bored, lonely, and adrift as a newly single, middle-aged woman. Meanwhile, Walt doesn’t have to contend with Meg’s sudden ostracization or any of the other tolls of remarrying; instead, he seems absently pleased to have found a wife so soon after being widowed. We are left, by the end, with the sense that Meg might remain bored and lonely in matrimony: “Lots of women would envy her in this position, and as she walked through the house…she admitted to herself that she was past caring.” One wonders what Oliver would have thought of Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner, which saw its theatrical release the year after her death.

But Oliver’s fiction does not dismiss the hope of love, family, or progress; it is more likely that her mind was fed by the delicious ambivalence that makes for good fiction. Her striving characters achieve our sympathy not merely because they are middle-class Americans or hope to be. More convincingly, they become poignant because America guarantees them nothing, and yet they are obliged to take their gambles. Jenny, the rural young woman at the center of “Before Twilight,” considers whether to do a sit-in with her friends:

Jenny held [the pamphlets] so the glow outlined the words on the cover—Freedom Now, Americans All.… Not that Mama would care, she reasoned, but still there was no sense in taking chances. Mama’s brother Harold had gone around telling everybody that membership in CORE was dangerous in this part of the country. He almost threw a fit when she even mentioned the word.

We like to think that agitators for racial justice were steadfast in their heroism, perhaps because this pose would join them to America’s other great myths. But organizing posed serious dangers to Southern Blacks—not just bodily but also psychic and economic harm—and the actual courage required to undertake the work of politics undoes any sanitized understanding of the civil rights movement. Young people like Jenny had much to lose but still staged actions in the small, nondescript towns of the South, towns so small that they offered neither protection from racism nor widespread recognition of their protest. When the youth are arrested, the gruesomeness that we and Jenny anticipate merely turns to condescension. “The officer tells me you children are a little confused,” says the white pastor brought in to counsel them at the jail. Did the protest even work—and if so, for whom? What would it mean to say it had?

The specter of racial terror, depicted with a plain but chilling sort of eloquence, has earned Oliver comparisons to Jordan Peele. Such stories as “Mint Juleps Not Served Here” and “No Brown Sugar in Anybody’s Milk” mark Oliver as prescient in adapting gothic conceits to the bleak surreality of a segregated society. In the latter, a white family’s beautiful house gives a young Black maid named Essie T. a frightful scene, while in the former, a Black couple goes to nightmarish lengths to protect their family’s life outside society. But other stories like “Before Twilight” might better be compared to Clarice Lispector’s housewives, whose banal days in modern Brazil turn on epiphany rather than discrete events. If these stories can be anecdotal, their subtlety of characterization, dialogue, and morality elevate them beyond the slice-of-life.

Some of the more straightforward stories in Neighbors might have become a larger and more evocative work, had Oliver lived long enough. Libby, a domestic worker and mother of five, must have been one of her favorite characters: She is the central figure in both “Health Service” and “Traffic Jam.” In the first, Oliver indicts the South’s failure to provide medical care to rural Black children, an abandonment that by many measures has continued. “Traffic Jam” sees Libby employed at the home of a Mrs. Nelson, who pays part of Libby’s wages in unsolicited advice and invasive questions, as if in a terse parody of Southern hospitality’s more patronizing (and racist) elements.

In the unsung lives of Black domestics, Oliver seems to have found inspiration. Libby has yet another avatar in the younger Essie T. of “No Brown Sugar in Anybody’s Milk,” which The Paris Review published last summer. But Essie’s tale is a radically different narrative. In this doubling and others, one can sense Oliver’s good instincts about writing: A breadth of subjects may not, in the end, matter so much as a deep engagement with one or two, and a careful manipulation of tone, form, and perspective until related stories yield distinct flavors. Libby and Essie are familiar figures, put-upon Black women trying their best despite low-paying work and the caregiver’s usual burdens. Oliver’s mission here was to give Libby and Essie the interiority and agency that too many Mrs. Nelsons did not. Libby’s mind is constantly surveying the contours of her lack—what choices matter most when one has few. She sneaks some of Mrs. Nelson’s wasted food into her bag, thinking of her five children.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →The border separating adults and children makes a return in Neighbors time and time again; most of the stories find children and youth in moments of crisis that they or their parents attempt to ameliorate. Oliver understood the sad paradox that children do not choose to be born into a benighted world, whose horrors and inequities they endure most painfully. Think of Tommy and Winifred’s employment as social experiments, but also of what Libby, the domestic, does for her kids, the risk Nora’s mother takes when she moves her progeny to Chicago in “Key to the City,” or the rambunctious Latonya from “Our Trip to the Nature Museum,” who cannot help but give her beleaguered teacher a hard time.

Young adulthood, on the other hand, becomes Oliver’s own metaphor for all sorts of thresholds, political and personal. The adolescents and college students in her stories are busy determining what structures of belief are worthwhile and which are to be refused, as Oliver herself was doing in her writing. “When the Apples Are Ripe” is in one sense about young, white Doug’s decision to become a Freedom Rider despite his father’s admonition to concentrate on school. But the real center of the story is his younger brother Jonnie, who overhears the dispute without quite grasping much, except that his dear brother will soon be far from home. We gather that, in a politically moderate, suburban setting like this one, no one really cares to explain to children what it means to be white, or why the Freedom Riders might think volunteering is so necessary. Their Black compatriots are an abstraction, if a pressing one. (That this dynamic remains so timely is galling.) Jonnie is equally intrigued by the family’s neighbor Mrs. Gilley, an eccentric, elderly woman in a decrepit house who appears to be a last remnant of the slave-owning Southern aristocracy. Mrs. Gilley makes an enigmatic scion: Her dog is named General Lee, but she long ago gave up her ancestors’ plantation and seems resigned to the coming societal changes. Her moral position is never settled, and we leave wondering if the assumptions Jonnie’s family makes about her are confirmed or refuted by the story’s end. Segregation’s evil is clear, but Oliver still pondered how both sides of the color line would be changed by its blurring, what responsibilities would attend mere integration. We are all neighbors, after all—sharing one domain while pretending to be kings of our own.

More from The Nation

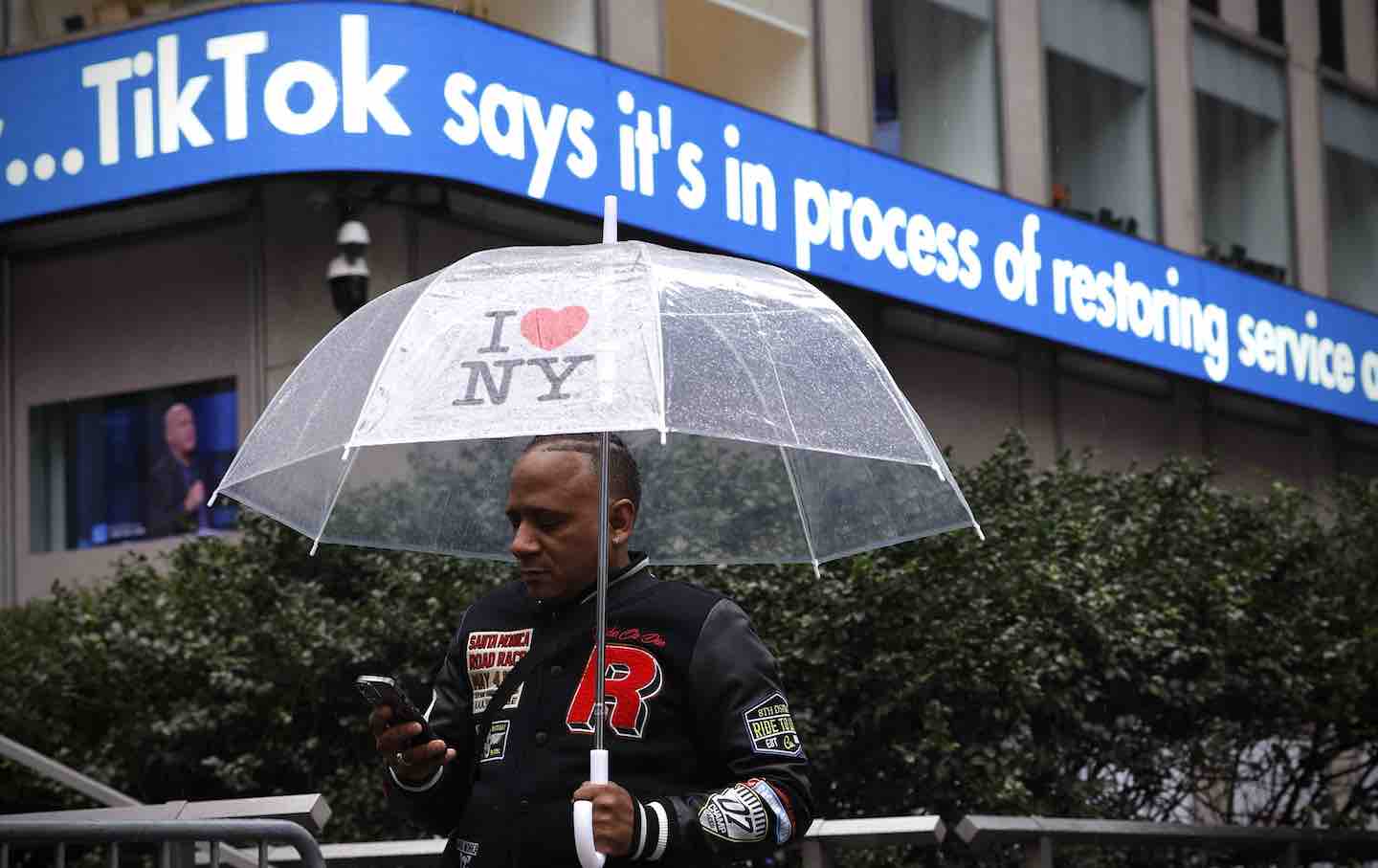

TikTok’s Incomplete Story TikTok’s Incomplete Story

The company has transformed the very nature of social media, and in the process it has mutated as well—from tech unicorn to geopolitical chesspiece.

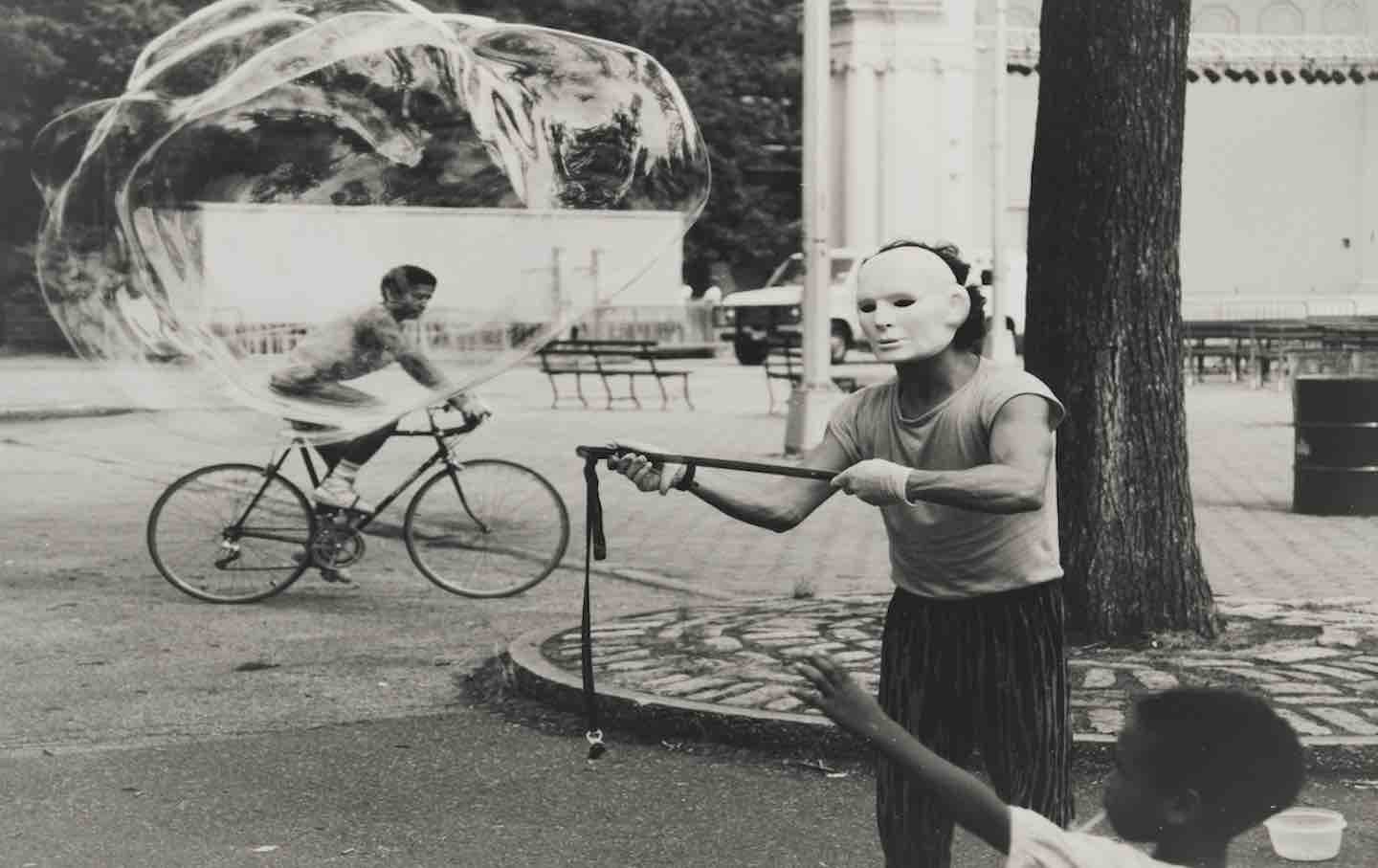

Did We Get the History of Modern American Art Wrong? Did We Get the History of Modern American Art Wrong?

The standard story of 1960s arts is one of Abstract Expressionism leading into Pop Art and minimalism. A Whitney show proposes an altogether different one centered on surrealism.

The Bleak History of the American Work Ethic The Bleak History of the American Work Ethic

In Make Your Own Job, Erik Baker shows just how long Americans have scrambled to pile work on top of work—and at what cost.

The Banal Spectacle of “Avatar: Fire and Ash” The Banal Spectacle of “Avatar: Fire and Ash”

Has James Cameron’s epic sci-fi series run aground?

The Dislocations of Shuang Xuetao The Dislocations of Shuang Xuetao

The Chinese writer’s fiction details how the country transformed on an intimate level after the Cultural Revolution.

An Absurdist Novel That Tries to Make Sense of the Ukraine War An Absurdist Novel That Tries to Make Sense of the Ukraine War

Maria Reva’s Endling is at once a postmodern caper and an autobiographical work that explores how ordinary people navigate a catastrophe.