How Young Kashmiris Shape the Struggle for Self-Determination

Silenced and sidelined and between nation-states, young people are organizing for an independent Kashmir.

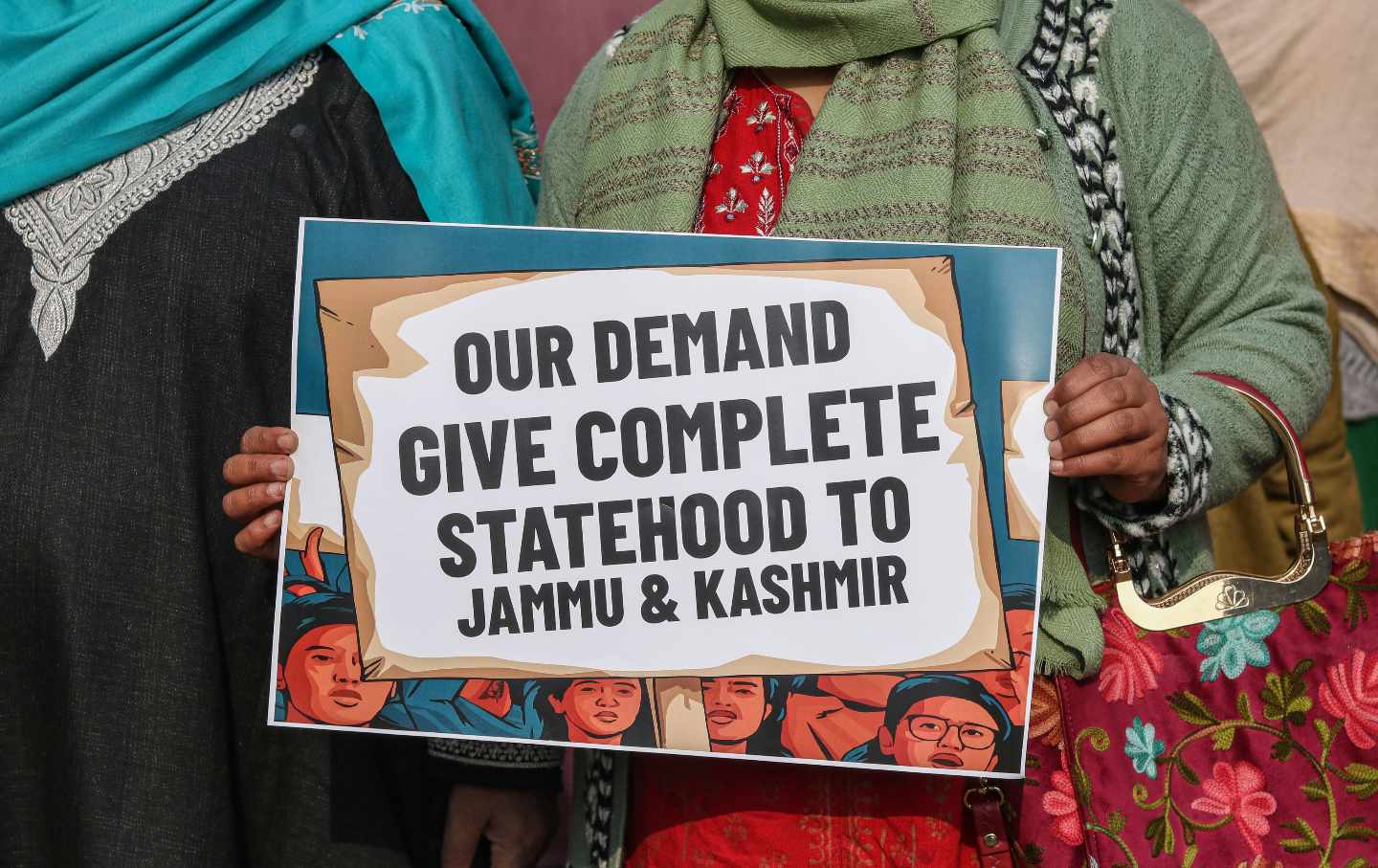

A member of the Jammu and Kashmir Pradesh Congress Committee holds a sign during a protest.

(Firdous Nazir / Getty)

Growing up under “the shadow of a gun,” Sadiq chose to pick up a camera. As a photographer and writer, Sadiq covers national politics and human rights in Kashmir, providing on the ground reporting for local and international outlets, including Al Jazeera, Jacobin, and The Quint. It’s dangerous work. “We could be jailed,” Sadiq said, who requested a pseudonym to protect his safety. “Are they watching me? Are they watching my family?” he asks in the field. “What’s going to happen next?”

Kashmir is one of the most militarized regions in the world, located in the northwestern region of the Indian subcontinent between mountain ranges and rivers. For centuries, Kashmir has been governed by non-Kashmiris, living instead under the rule of various empires—including the Mughals, Afghans, Sikhs, and Dogras prior to the subcontinent’s partition. Under 101 years of Dogra rule, Kashmiris could not hold land, control crops, or speak their native language, as Koshur was replaced with Urdu. This rule was marked by Hindu supremacy, where Kashmiri Muslims paid taxes for getting married and faced restrictions on religious practices.

After the partition, India and Pakistan fought multiple wars with Kashmir at the center. Ever since, Kashmiris in the borderlands have been sidelined and silenced, living under the realities of militarization, occupation, and international conflict.

Yet Kashmir’s history is also marked by a decolonial struggle for self-determination and autonomy. As a continuation of this struggle, some Kashmiris have turned toward sharing their stories—an act that carries high costs.

The weeks following India and Pakistan’s May 10 ceasefire were some of the most unpredictable in recent memory. For those living near the Line of Control, the military control border separating Indian-administered Kashmir from Pakistani-administered Kashmir, tensions between India and Pakistan halted Kashmir’s day-to-day life.

Caught in the crossfire were Kashmiris born between borders. “Who was the battlefield? What was the collateral damage? It was us. Two countries with nuclear weapons were on the verge of war, we knew that the battleground was us. That is what uncertainty is like,” said Zahra, a 23-year-old journalist who requested a pseudonym. She was drawn to journalism as a way to push back against the narratives manufactured by India through media blockades, censorship, and the targeting of the Kashmiri press. “Stories were all around,” she said, describing her passion to write about the cultural symbols of Kashmiri identity, from Kashmir’s language to its literature.

Kashmiri resistance dates back well before partition. In 1931, thousands of Kashmiris protested the Hindu-supremacist, autocratic Dogra rule. On July 13 of that year, now remembered as Martyrs Day, 22 protesters were shot by police during the adhaan, the Muslim call to prayer. In 1947, amid the partition, the Dogra ruler signed the Instrument of Accession, which gave India control over Kashmir. What followed was a 1948 war between India and Pakistan, which resulted in India occupying two-thirds of Kashmir, Pakistan one-third, and the creation of the Line of Control.

In 2016, following India’s military killing of 21-year-old militant commander Burhan Wani, India suspended mobile and cell phone services for four months, as well as local publications like the Kashmir Reader, in an attempt to suppress protest and erase documentation of the reality of living under occupation. For Ibrahim, a 27-year-old Kashmiri journalist, writing about the protests against Wani’s killing and the militarization of Kashmir marked the beginning of his journalism career. But his being one of the only journalists in his area covering this story placed a target on his back.

“We used to get summoned to the local police station,” Ibrahim said. “I was highlighting what was happening in Kashmir and what was happening in the field. I was doing my work, but for them, it was anti-national.”

In August of 2019, the Indian government revoked Article 370. The law had previously granted Kashmir autonomy for internal administration and limited sovereignty—except in matters of defense, foreign affairs, and communications. Since 1949, under the article, Kashmir has held special status with its own flag and Constitution. When it was revoked, nonresidents and tourists were ordered to leave the region, while an additional 40,000 security forces marched into the valley. Like in 2016, India once again suspended mobile and cell phone services. But this time, they wouldn’t restore communications until over a year later.

Ibrahim recalled this as the moment that Kashmir became an “open prison.” Journalism had served as a record of crimes under occupation, documenting how Kashmiris chose to resist, but then this record began to disappear. Journalists, including Ibrahim, saw their work being removed from archives and websites. “If you are putting a post on Facebook as a journalist, the next day, you don’t know what’s going to happen,” Ibrahim said, who also requested a pseudonym. “They will raid your house. They can take your father or brother.… One quote can land us in jail.” Amid ongoing press restrictions, Ibrahim writes under a separate name from his family’s to protect their safety.

“We are brought up in a way that we’re always prepared for the worst, and we’re always told ‘aaj ka kaam aaj karo,” Zahra said which translates to ‘do today’s work today, don’t leave it till tomorrow.’ “You cannot trust if you’ll see tomorrow,” said Zahra. “Somewhere in between all of this is a common Kashmiri who leaves their house in the morning, and comes back from work in the evening. Now their livelihood is uncertain.”

The uncertainty Zahra describes was felt by both Kashmiris in the valley and students in India following the Pahalgam attack on April 22, which killed 26 people in Indian-administered Kashmir this year. Within days of the attack, 18 Kashmiri students at Indian universities in Uttarakhand, Punjab, and Delhi reported violence and threats, and some “branded as terrorists,” said Nasir Khuehami, a representative of the Jammu and Kashmir Students Association.

For some students, any academic work about Kashmir has been a source of targeting. Meena, a Kashmiri student studying in Punjab who requested a pseudonym, wrote her thesis about the intangible elements of Kashmiri life. Inspired by the memory of her neighborhood in Kashmir, she wanted to exist as a Kashmiri beyond “conflict and occupation.” But in the days following the Pahalgam attack, she felt as if conflict was the only lens she had as she experienced verbal threats and online harassment. “Are you a Kashmiri? Do you have bombs with you?,” she recalled people asking her.

The violence against Kashmiris in India extended beyond colleges through threatening workplaces and livelihood. Azeem, a salesman based in Uttrakhand who requested a pseudonym, sells Kashmiri handicrafts and clothes. Before he heard the news of Pahalgam, 30 men with sticks attacked his business, threatening him to leave India. “If other people weren’t there when it happened, then I don’t know what would have happened to me,” he said.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →As Indian nationalism targets Kashmiris in India, its impact is felt by those in the diaspora. Fatima, a 21-year-old Kashmiri American student, longs to see the side of Kashmir beyond the Line of Control—a journey she hasn’t been able to make because of India’s revocation of Pakistani visas. Her family migrated from Indian-administered Kashmir to Pakistan-administered Kashmir during the 1947 partition. She seeks to exist beyond the India-Pakistan binary, with her dream being a Kashmir free of the violence of borders.

“When I say, ‘I’m Kashmiri,’ rather than either of the nationalities, I want to say, ‘I stand with the people of Kashmir,’” Fatima said. “I want Kashmir to decide their future.”

Sadiq holds hope for the future. To tell Kashmir’s story—and to be a part of it—is to be one step closer to freedom. He holds on to hope through the valley’s shared vision and calls for self-determination, no matter how small each step or story may feel. “The dream is of a world as a bridge of neighbors, not as enemies.… We dream of a future written by Kashmiri hands and not dictated by distant capitals, but instead from love for the people of their past and their rights to the future where Kashmir is not a headline but a homeland.”

Support independent journalism that does not fall in line

Even before February 28, the reasons for Donald Trump’s imploding approval rating were abundantly clear: untrammeled corruption and personal enrichment to the tune of billions of dollars during an affordability crisis, a foreign policy guided only by his own derelict sense of morality, and the deployment of a murderous campaign of occupation, detention, and deportation on American streets.

Now an undeclared, unauthorized, unpopular, and unconstitutional war of aggression against Iran has spread like wildfire through the region and into Europe. A new “forever war”—with an ever-increasing likelihood of American troops on the ground—may very well be upon us.

As we’ve seen over and over, this administration uses lies, misdirection, and attempts to flood the zone to justify its abuses of power at home and abroad. Just as Trump, Marco Rubio, and Pete Hegseth offer erratic and contradictory rationales for the attacks on Iran, the administration is also spreading the lie that the upcoming midterm elections are under threat from noncitizens on voter rolls. When these lies go unchecked, they become the basis for further authoritarian encroachment and war.

In these dark times, independent journalism is uniquely able to uncover the falsehoods that threaten our republic—and civilians around the world—and shine a bright light on the truth.

The Nation’s experienced team of writers, editors, and fact-checkers understands the scale of what we’re up against and the urgency with which we have to act. That’s why we’re publishing critical reporting and analysis of the war on Iran, ICE violence at home, new forms of voter suppression emerging in the courts, and much more.

But this journalism is possible only with your support.

This March, The Nation needs to raise $50,000 to ensure that we have the resources for reporting and analysis that sets the record straight and empowers people of conscience to organize. Will you donate today?

More from The Nation

Jesse Jackson Still Provides Light in These Dark Times Jesse Jackson Still Provides Light in These Dark Times

We would be wise to follow the path he forged.

Jesse Jackson Gave Peace a Chance Jesse Jackson Gave Peace a Chance

The iconic civil rights leader, who has died at 84, made anti-war and pro-diplomacy politics central to his presidential bids and his lifelong activism.

ICE Melts in the Minneapolis Winter ICE Melts in the Minneapolis Winter

Now it’s time to abolish the agency and impeach Kristi Noem.

How 2 University Freshman Are Tracking ICE Enforcement Actions Across the Country How 2 University Freshman Are Tracking ICE Enforcement Actions Across the Country

With ICE Map, Rice University students Jack Vu and Abby Manuel hope to help communities understand where immigration enforcement activity is happening and how it unfolds in real t...

Meet the Young Organizers Survival Corps Meet the Young Organizers Survival Corps

Young organizers from around the country gathered at Haley Farm to study past social movements and train in the tactics of nonviolent resistance and grassroots organizing.

I Fled the US to Escape the Security State. Instead, It Followed Me. I Fled the US to Escape the Security State. Instead, It Followed Me.

My recent detention at Heathrow shows that the architecture of state repression knows no borders.