What the Pro-Choice Movement Can Learn From Those Who Overturned Roe

What the Pro-Choice Movement Can Learn From Those Who Overturned “Roe”

The anti-abortion movement was methodical and radical at the same time. The abortion-rights movement must be too.

In times of full-scale attack like the one now upon us, social movements face two paths. They can run defense through the traditional legal and political channels to protect the remaining scraps of what they’ve fought for. Or they can go on offense and work outside the system, devising risky legal experiments and taking to the streets. Under Donald Trump, Planned Parenthood—the nation’s largest provider of reproductive-health services—has lost hundreds of millions of dollars in federal funding and closed approximately 50 clinics in the past year alone. In response, the organization has hewed to the defensive path it became known for during the half-century that abortion was legal nationwide. It has often prioritized protecting its own funding at the cost of taking on bigger fights. Confronted by restrictive laws, its affiliates often chose the path of least risk rather than greatest access, sometimes even ceasing to provide abortions where they remained legal, as Irin Carmon wrote in a recent article for New York magazine. In that article, the scholar Michele Goodwin described Planned Parenthood’s long-standing adherence to its defensive strategy as the organization’s “good-girl problem.” Four years after Roe’s demise, it’s easy to see this path as a resounding failure.

But as the immigrant-rights movement is showing us now, social movements are strongest when they manage to run both offense and defense at the same time. Today, immigration attorneys are fighting in court to stop whatever individual deportations they can, while ordinary people armed only with their phones document ICE’s brutality. For the abortion-rights movement, the best historical example of how this approach can succeed comes from its own enemies.

I’ve spent the past two years writing a book on how abortion opponents built a grassroots movement to do what once felt impossible: overturn Roe v. Wade. Titled Killers of Roe, it’s a whodunit that looks at the behind-the-scenes figures who were responsible for the death of abortion rights. Tracing this history, I saw how abortion opponents won because they ran down both roads at once. Legal organizations like the National Right to Life Committee (NRLC) were the movement’s “good girls.” They lobbied Republican politicians to restrict abortion and for decades accepted incremental victories. Eventually, the Alliance Defending Freedom (ADF) took one of these incremental victories to the Supreme Court, which ultimately toppled Roe. But these groups would not have succeeded without the movement’s “bad girls.” Randall Terry staged “rescue” blockades of clinics in the 1980s and ’90s. Monica Migliorino Miller pulled fetuses out of dumpsters in the dark of night and took pictures of them to put on posters. Extremists bombed clinics and murdered doctors and receptionists. These “bad girls” generated a false sense that legal abortion was controversial, even though most Americans supported it.

Within the anti-abortion movement, the “good girls” and “bad girls” often fought. But in the hindsight afforded by history, the rifts in the movement look like strengths. Joseph Scheidler, the 6-foot-4, fedora-wearing godfather of the anti-abortion movement, was fired as director of the NRLC’s Illinois affiliate for his militant tactics. But his clinic sit-ins and displays of bloody fetuses galvanized true believers and helped spark the “rescue” movement. In 2021, nine months before the ADF would prevail in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization, the case that overturned Roe, former Texas solicitor general Jonathan Mitchell’s wild idea to outsource the enforcement of abortion laws to private citizens succeeded in banning most abortions in Texas.

So what can progressives learn from the anti-abortion movement’s victory?

Roe established a baseline of legal protection that the abortion-rights movement needed to defend. But this strategy alone was never enough. It overlooked the reality that many women of color and low-income people lacked access to abortion even with Roe in effect, under policies like the Hyde Amendment, the ban on the federal funding of abortion first passed in 1976. While researching my book, I came upon certain historical moments that felt like turning points, such as January of 1981. Ronald Reagan had just been elected, the Supreme Court had upheld the Hyde Amendment, and abortion opponents in Congress were floating a “Human Life Amendment” to ban abortion under the Constitution.

Six days before Reagan’s inauguration, the leaders of national pro-choice organizations—including Planned Parenthood, NARAL, NOW, and the ACLU—gathered for a meeting. The group identified “four areas in which it wanted to direct further discussion,” one of which was “Poor Women.” “The discussion of poor women produced agreement that this issue must be kept alive but that the larger issue of a Human Life Amendment must take precedence for the time being,” the notes read.

When I discovered this memo in the NARAL archives, I felt like I had found a smoking gun. There it was: the movement’s decision to deprioritize the Hyde Amendment. Even the movement’s most famous “bad girls” were part of this agreement. Faye Wattleton, who had become the first Black woman to lead Planned Parenthood in 1978 and announced a controversial goal of restoring Medicaid funding for abortion, made a case for the defensive approach. “Faye expressed a belief that the medicaid issue is a separate phenomenon,” the notes read. “It was a bellweather [sic] issue, she said, regarding people’s feelings about the poor, public funding, etc. She thinks it best now to hold on to established ground.”

When I asked Wattleton about this moment, she told me that she didn’t believe the movement ever completely gave up on Hyde, even though the Human Life Amendment presented “an even more fundamental challenge” that it needed to confront. Indeed, the decision wasn’t as black-and-white as it looked on paper. The leaders would continue to discuss ways to restore Medicaid funding in states where it seemed feasible. But Wattleton was a nurse by training. So she did what Planned Parenthood—an organization that has for decades relied on federal funds to provide healthcare to millions—has always done: She ran triage and took on the biggest threat first.

In 1993, two paths again diverged for the movement over public funding. This time, the fork in the road would divide advocates. Democrats controlled Congress and the presidency for the first time in over a decade, and this was their shot to enshrine legal abortion even if Roe someday fell. Planned Parenthood and NARAL wanted to pass a bill to codify Roe. But a coalition from the left that included the National Black Women’s Health Project and NOW demanded that the legislation address parental-consent requirements and Medicaid funding, lest it leave the most vulnerable behind. The bill didn’t pass, and the more progressive organizations took the blame. But you could also blame the movement’s “good girl” politics, which had reigned for so long that any insistence on protections beyond Roe sounded unreasonable.

The issue came to a head again almost two decades later, during the debates over the Affordable Care Act. Barack Obama struck a deal with anti-abortion Democrats to accept restrictions on the private coverage of abortion and to reaffirm the Hyde Amendment in an executive order. Nancy Keenan, who was head of NARAL at the time, told me the White House had reached out to Planned Parenthood and NARAL for their quiet endorsement before sealing the deal. Groups led by women of color as well as grassroots organizations that had stepped up to fund abortions after Hyde cut off federal Medicaid coverage were angry at the outcome. Apparently, electing a Democratic president wasn’t enough to protect abortion rights. So those groups devised the abortion-rights movement’s greatest unsung success in a generation: a campaign called All* Above All, which took direct aim at Hyde, amassing 71 cosponsors on a historic bill to repeal the ban. In the process, All* Above All succeeded in convincing a number of prominent Democrats to reverse their long-standing support of the amendment, including most notably Joe Biden, who came out against Hyde during his presidential campaign after supporting it for decades.

The campaign initially caused a rift in the movement, advocates told me; one early meeting got so heated that a high-level pro-choice operative stormed out of the room. But in hindsight, these ruptures can be seen not as weaknesses but as growing pains. They were early signs of a movement finally learning to run down two roads at once.

In the wake of Roe’s fall, unconventional paths have been extraordinarily successful. Legal strategists from outside the established groups banded together to devise and lobby for “shield laws,” untested new measures to protect providers in blue states who ship abortion pills to places like Texas. A number of the biggest pro-choice organizations in the country, including Planned Parenthood, cautioned against this strategy. But others in the movement did it anyway, and thanks in large part to these laws—and to the doctors who risk retribution from red states to mail abortion medications—the number of abortions has risen every year since the Supreme Court overturned Roe. Let that sink in for a minute. The movement didn’t get there through one path only. Most abortions still take place in brick-and-mortar clinics. And the victory is far from complete. Abortion restrictions are still forcing people to continue their pregnancies, and sometimes these restrictions are killing them. But as Planned Parenthood and independent clinics were keeping whatever doors they could open, the bad girls were breaking the system and building a new one.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →If we can learn anything from the anti-abortion movement’s success, it’s that sometimes you win not by unifying behind one strategy but by doing it all. Unlike the proverbial traveler in Robert Frost’s poem “The Road Not Taken,” social movements don’t have to choose. They can—and, history indicates, they must—take both roads at once.

Your support makes stories like this possible

From Minneapolis to Venezuela, from Gaza to Washington, DC, this is a time of staggering chaos, cruelty, and violence.

Unlike other publications that parrot the views of authoritarians, billionaires, and corporations, The Nation publishes stories that hold the powerful to account and center the communities too often denied a voice in the national media—stories like the one you’ve just read.

Each day, our journalism cuts through lies and distortions, contextualizes the developments reshaping politics around the globe, and advances progressive ideas that oxygenate our movements and instigate change in the halls of power.

This independent journalism is only possible with the support of our readers. If you want to see more urgent coverage like this, please donate to The Nation today.

More from The Nation

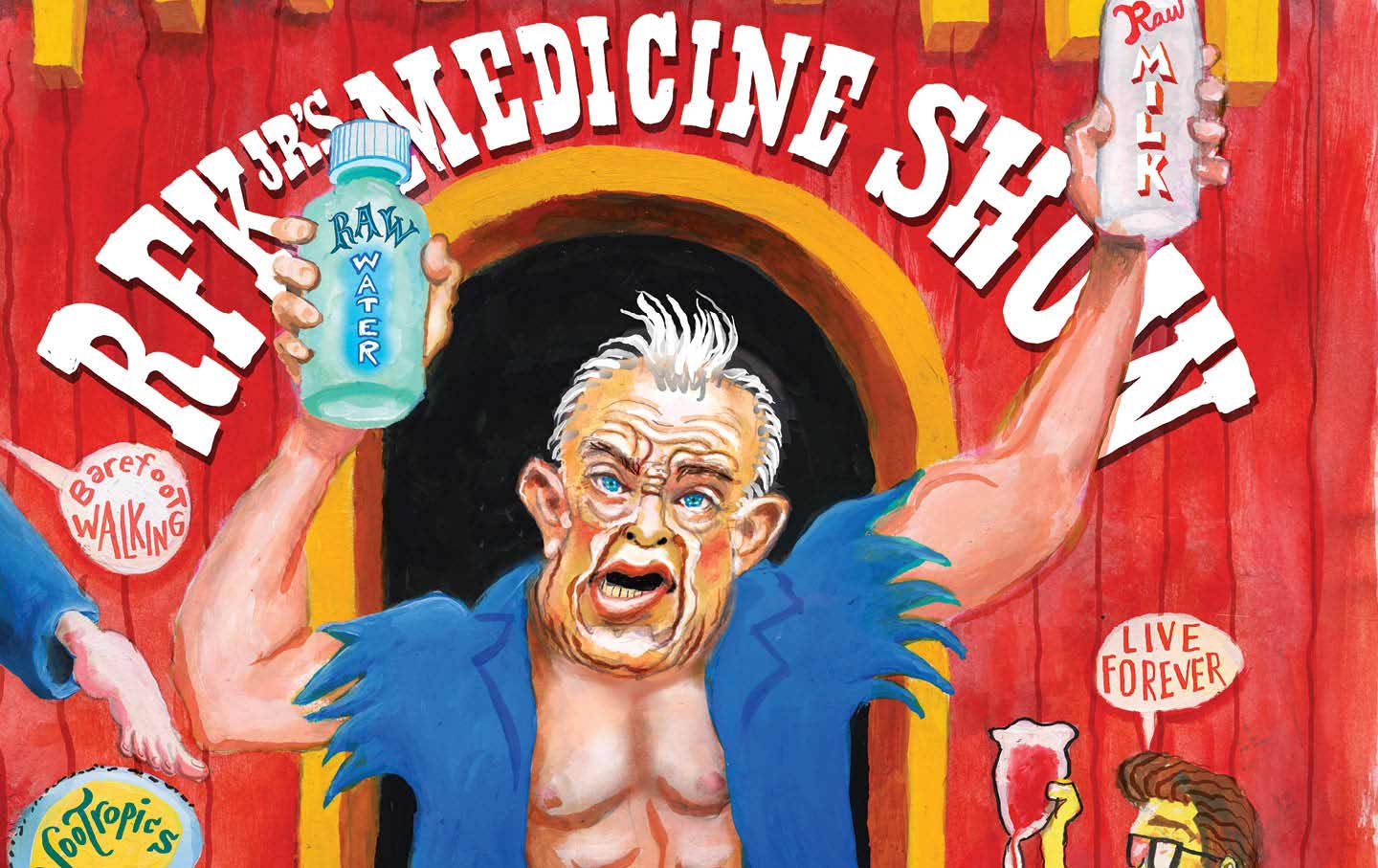

How the Far Right Won the Food Wars How the Far Right Won the Food Wars

RFK’s MAHA spectacle offers an object lesson in how the left cedes fertile political territory.

How Stephen Miller Became the Power Behind the Throne How Stephen Miller Became the Power Behind the Throne

Miller was not elected. Nor are he or his policies popular. Yet he continues to hold uncommon sway in the administration.

The Racist Lie Behind ICE’s Mission in Minneapolis The Racist Lie Behind ICE’s Mission in Minneapolis

It was never about straightforward enforcement of immigration law.

Sunnyside Yard and the Quest for Affordable Housing in New York Sunnyside Yard and the Quest for Affordable Housing in New York

Constructing new residential buildings, let alone those with rental units that New Yorkers can afford, is never an easy task.

How Capitalism Transformed the Natural World How Capitalism Transformed the Natural World

In her new book, Alyssa Battistoni explores how nature came to be treated as a supposedly cost-free supplement of capital accumulation.

Bad Bunny’s Technicolor Halftime Stole the Super Bowl Bad Bunny’s Technicolor Halftime Stole the Super Bowl

The Puerto Rican artist’s performance was a gleeful rebuke of Trump’s death cult and a celebration of life.