The Enclosure of All

How capitalism transformed the natural world

How Capitalism Transformed the Natural World

In her new book, Alyssa Battistoni explores how nature came to be treated as a supposedly cost-free supplement of capital accumulation.

Anew kind of politics is taking shape in Japan. This past fall, the Liberal Democratic Party’s Sanae Takaichi, who had long been regarded as an outlier on the party’s right flank, became the country’s first female prime minister. This was no aberrational phenomenon: Takaichi entered office with approval ratings near 70 percent. Her predecessor, Shigeru Ishiba, had seen his support collapse to barely 30 percent after the Liberal Democrats’ historic defeat in the July elections for the House of Councillors, analogous to the US Senate.

Books in review

Free Gifts: Capitalism and the Politics of Nature

Buy this bookPart of Takaichi’s rise was fueled by heat. After the rainy season ended unusually early in much of Japan, the country saw a third straight year of record-breaking temperatures as the global average increase approaches the 1.5ºC target set by the Paris Agreement. Rice yields plummeted, and the resulting “rice shock” deepened public anxiety in an already inflationary economy and forced the government to release its emergency grain reserves for the first time.

Out of this economic and ecological turmoil came a right-wing-populist turn. Enraged at the Ishiba administration’s tepid response, many voters turned to Sanseito (the “Do-It-Yourself Party”), whose platform combined promises of food self-sufficiency and support for organic farming with a rhetoric of “Japanese First.” Over time, its mix of nationalism, conspiracy politics, and environmental populism curdled further into xenophobia and opposition to climate action, taking the form of attacks on immigrants, renewable energy, and vaccines. To win back the many defectors to Sanseito, the Liberal Democratic Party swerved ever more to the right and elevated Takaichi to power.

Sound familiar? From Donald Trump in the United States and Javier Milei in Argentina to the far-right resurgence in many parts of Europe, the pattern is unmistakable: The convergence of ecological disaster, resource scarcity, a flagging and disoriented liberalism, and climate-driven displacement leads to an authoritarian turn. Nature itself has ceased to be a neutral backdrop to politics and has become instead a primary terrain of conflict—as seen in the fights over arable land and rare metals, in the inflation driven by crop failures and energy volatility, and in the desperate movements of climate refugees.

As a result, if we hope to avoid an era of “climate barbarism,” in which we revert to some Hobbesian “state of nature,” a “war of all against all,” argues the political theorist Alyssa Battistoni, how we value nature becomes a decisive question for the future of democracy and freedom. How can we share scarce metals and soils while preserving the basic conditions of collective survival—breathable air, drinkable water, and a habitable climate? The problem is not merely how much we can take from the earth, but how we might reorganize society so that freedom no longer depends on the oppression of others or the expropriation of nature.

These questions are at the center of Battistoni’s new book, Free Gifts: Capitalism and the Politics of Nature, in which she expands on her earlier work in eco-socialist theory (including A Planet to Win: Why We Need a Green New Deal, which she cowrote with Kate Aronoff, Daniel Aldana Cohen, and Thea Riofrancos) to offer a systematic reexamination of how capitalism organizes and transforms the natural world. In Free Gifts, Battistoni traces a long intellectual arc—from the classical political economists and Karl Marx’s critique of value to 20th-century feminism and contemporary ecological thought—to explain how nature came to be treated as the supposedly cost-free support of capital accumulation. Along the way, she also shows that capitalism’s current environmental crisis is not simply the result of ignoring nature’s worth, but of depending on its very non-valuation to justify an endless extraction of resources that appears to exist outside the sphere of price.

Battistoni’s central argument is both simple and radical: Capitalism persists and develops only by systematically undervaluing nature, treating its forces and resources as “free gifts.” Battistoni uses this particular term for a reason: It comes from both classical political economy and Marxist critique and, she argues, refers to a “distinctively capitalist” phenomenon—the way in which our current social and economic systems treat nature as a costless input.

While we often think about the process in which the earth and its precious resources—water, land, air, oil, natural gas, minerals, forests, and even the atmosphere itself—were enclosed and turned into commodities, Battistoni emphasizes that, at the point of this enclosure and even afterward, they have often remained free to capital, even if they are never free to the wider society. A process of devaluation has taken place to create the world we live in: Capital extracts from the earth, but often without paying for any of that extraction’s costs.

As a result, Battistoni observes, the true social and ecological costs of carbon emissions, microplastics pollution, or Amazonian deforestation do not appear in market prices, though their burdens are imposed on us all. This structural disjuncture fuels rampant ecological devastation and what economists euphemistically refer to as the “tragedy of the commons.”

While mainstream neoclassical economics acknowledges these problems as “negative externalities” and proposes corrective pricing mechanisms or valuation models for “ecosystem services” to internalize the true costs, Battistoni rejects the premise underlying such solutions. For her, the failure to value nature is not simply a technical flaw in measurement; it is intrinsic to capitalism’s way of valuing human labor as a commodity.

Battistoni argues that capitalism contains within it a distinct form of “humanism.” It does not prioritize human life or exalt humanity’s unique characteristics, but it does privilege human beings over nonhuman nature in another way: It views them as capable of producing value through their labor. As a result, that which is nonhuman is considered outside the realm of any meaningful valuation. This is discernible in the fact that capital at least has to pay wages for workers, while the value that is extracted from nature goes unremunerated. As long as this fundamental devaluation remains the essential characteristic of the social system, then even when parts of nature are priced, they enter the market as mere commodities that can be bought, traded, and appropriated.

To address capitalism’s tendency to appropriate natural elements and forces, Battistoni does not propose new techniques for valuation. Rather than a technocratic solution that would regulate nature’s market from above, she argues for a political resolution that empowers people to once again decide what gets valued, and how. In place of market fixes, she calls for a reorganization of social life that would allow labor, and humanity in general, to reclaim its capacity to choose what counts as value and what kinds of work—both human and nonhuman—should sustain the world. For Battistoni, ultimately, ecological survival is also a struggle for freedom and collective self-determination.

To tease out these implications, she starts by asking how capitalism enabled nature’s devaluation in the first place. To do so, Battistoni draws on two distinct elements of Marx’s critique of political economy: She investigates how our relationship to the environment is part of a fundamentally unified biophysical process that Marx called the “universal metabolism of nature,” and she examines how this metabolic relationship between humans and nature is then mediated and reshaped by the way that capitalism turns everything produced by human labor into one kind of value or another to exchange on a market.

As Battistoni reminds us, there has always been something called “use value.” The production of a desk, for example, marks the material transformation of wood into an object with a value defined by its use. (It is the thing we would use to write big books about political economy on, for example.) But under capitalism, a second process takes place: the creation of a commodity whose primary purpose is the realization of the profit found in its “exchange value.” Unlike use value, which is firmly rooted in material utility and the more immediate metabolic relationship between humanity and nature, exchange value does not exist in nature at all—it is a purely social form unique to how profits are extracted in a capitalist system of production.

Battistoni points out, however, that this does not make it an illusion. The value of goods when exchanged exerts immense power over our desires, behaviors, and institutions. Above all else, it is the reason why the economy is organized in the way that it currently is. It also has a transformative effect, Battistoni notes, on how we metabolize nature. The expansion of commodity production, driven by the imperative to maximize profit, systematically transforms and reshapes our metabolic relationship with nature, leading to serious disruptions.

Much as capitalism attempts to compel workers to work harder for longer hours, it also extracts more and more from nature, which changes the human body as well as the natural environment. Changes in bodies and nature, of course, happen all the time, but the problem is that the imperatives of extracting a profit from nature’s exchange value is dissociated from the concrete material processes of the natural world. In a capitalist system, the expanding and accelerating processes of industry and commerce have very little relation to the cycles and concrete changes found in nature, and so when the principles of exchange value dictate how nature is consumed, it changes the very life of the planet.

However, as Battistoni observes, nature does find ways of fighting back: The seasons, the limits of physical materials, and the sheer unruliness of the natural world, can hinder capital’s efforts to extract exchange value from it. There is also what she terms a “suprasumption”: “the existence of matter in excess of its subordination to capital, which often constitutes obstacles to accumulation.” In my book Karl Marx’s Ecosocialism, I described this same phenomenon as “nature against capital.” By refusing to conform to capitalist time frames and calculation—by eroding machinery, exhausting soil, unleashing unpredictable climatic feedbacks, and existing beyond total capture—the excesses of nature expose the fragility of accumulation itself. It reminds us that even the most abstract forms of value ultimately depend on a material world that will not be fully tamed.

Of course, we are not so lucky as to see nature rise up against capitalism as some kind of exploited biotariat. But simply realizing the impossibility of fully and arbitrarily manipulating the biophysical world for the sake of profit does make clear the limits of capital’s power over the earth. In this way, even if capitalism continues to ravage the natural world, nature can become a meaningful realm of political contestation. It is here that we recognize not only the limits of capitalism but also the capacity we possess to reshape society and nature in an entirely different way.

A capitalist system might seek to destructively exploit natural resources—forests, soils, oceans—because it incurs no direct costs for doing so. But, as Battistoni asserts, since it has to “abdicate” from certain domains, such as agriculture and care work, that resist full mechanization and industrialization, capitalism cannot fully subsume all of the world. There are places where freedom from its profit motives can exist and where humanity can find important footholds in the struggle for liberation: domains of life that challenge or transcend capital and offer spaces in which cooperation, regeneration, and nonmarket forms of value might and can continue to operate. What capital abandons as unprofitable can become a site of possible emancipation.

This concept of freedom lurking on the edges of capitalist domination serves as the underlying politics that Battistoni proposes in Free Gifts. “To offload the risk, both physical and financial, of the volatile and unpredictable patterns associated with many natural processes,” she writes, capital cedes some terrain—and it is here that new forms of struggle and cooperation can take root. The very sectors that capital neglects—such as care work, subsistence farming, and ecological restoration—can be the ones in which collective agency reasserts itself and alternative ways of organizing labor and valuing life can emerge. What capital leaves behind as waste or surplus or a simple absence of value can serve as the raw material for another politics: one grounded in reproduction, repair, and shared responsibility for the world.

If nature’s rebellion against capitalism opens new terrains for contestation, then the question becomes: What kinds of politics might emerge in these spaces cut off from capitalism? In the past, some of these arguments have been invoked in defense of an environmental politics seeking to align sustainability with justice—from the early eco-socialists to today’s degrowth and climate-justice movements. They have also surfaced on the right, where eco-fascists have weaponized ecological scarcity to justify exclusion, border violence, and racial hierarchy.

But for Battistoni, the ultimate stakes of this struggle over nature lie not only in ecology but also in freedom. Capitalist domination restricts human agency and autonomy not simply by exploiting labor but by forcing individuals to depend on markets and commodities for their survival. Even the most environmentally conscious worker cannot freely choose a sustainable way of life in a system that commodifies housing, mobility, food, and energy. A car may be depicted as the symbol of individual freedom, yet, in the United States, for instance, it is often a sheer necessity—one that burdens households with debt and dependence because of decades of underinvestment in public transportation.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →If nature becomes a realm organized by collective self-determination, then it can also become a vector for freedom in a world in which capitalism often creates domination. In this way, an ecological politics can serve as a foundation for socialist politics. Climate catastrophes already constrain our freedoms, and as temperatures continue to rise, the space for democratic choice and collective action will only narrow further. Yet these material limits do not need to erase the possibility of agency. In recognizing the natural world’s limits and contingencies, its seasons and metabolic cycles, and working with them rather than against them, socialists can achieve what they often struggle to realize when practicing their politics in those more traditional modes that set the politics of ecology to the side.

For Battistoni, this new eco-socialism means grounding politics in the kinds of labor and care that already engage with nature on its own terms and that help to sustain life itself. This could mean reclaiming public control over the resources and infrastructure required to live, or organizing workers in sectors like energy, agriculture, and caregiving. By learning to act within, rather than despite, the planet’s own rhythms, she suggests, radicals can turn ecological interdependence into a foundation for solidarity and democratic planning. The climate crisis is not merely a restriction on freedom; it is the terrain on which freedom can be redefined and practiced anew—in, against, and beyond capitalism.

All of this brings us to the most pressing question of our time: What institutions might enable the realization of a politics that both respects nature and achieves freedom through it? Unfortunately, Free Gifts offers few concrete answers. Battistoni is clear and precise in diagnosing capitalism’s structural devaluation of nature and its consequences for human freedom, and in offering the more abstract contours of a radical politics that might liberate us from them. But she remains deliberately cautious about prescribing institutional forms beyond capitalism. Should we imagine democratic control over ecological resources on a local, national, or planetary scale? What mechanisms could prevent the reemergence of market logics or new forms of domination while maintaining material coordination and solidarity? How can we revalue nature without commodifying it? These questions are left unresolved in the book.

Yet this may not necessarily be a weakness. Rather than offering a utopian blueprint, Battistoni urges us to confront the structural foundations of our present crisis and to begin the collective work of imagining alternatives. In this way, Free Gifts is not unlike much of Marx’s own work, which offered a rigorous critique of political economy rather than a prescriptive program and left the task of transformation to collective praxis and historical struggle. Battistoni follows Marx’s broader approach: to ground politics in the concrete analysis of existing conditions and to allow the forms of transformation to emerge flexibly from that understanding.

In a world increasingly marked by “climate barbarism”—a world in which floods, fires, and resource shortages fuel authoritarian responses rather than solidarity—this combined politics of nature and freedom might be the only sustainable alternative. In the United States, Japan, and many other nations, where climate policy remains hostage to fossil-capital interests and reactionary politicians mobilize anti-environmental rhetoric to consolidate power, Free Gifts offers an urgently needed reframing of our most basic assumptions about political and economic life. The challenge, Battistoni reminds us, is not merely to “fix” market failures through carbon pricing or so-called ESG metrics, but to recognize that capitalism’s very logic of devaluation drives ecological destruction, subordinates reproductive work, and erodes democratic freedom. The choice, then, is not between technocratic market corrections and a nostalgic retreat into an imagined “natural” past, both of which exist within the capitalist domination of nature. It is between a politics that treats nature as a site of capital’s domination and a democratic politics that centers collective agency within our shared and fragile ecological conditions.

In this sense, Free Gifts is more than a critique of capitalism—it is a call to action. Our burning planet, after all, is the only one we have, so we must find or create spaces of freedom upon it.

Your support makes stories like this possible

From Minneapolis to Venezuela, from Gaza to Washington, DC, this is a time of staggering chaos, cruelty, and violence.

Unlike other publications that parrot the views of authoritarians, billionaires, and corporations, The Nation publishes stories that hold the powerful to account and center the communities too often denied a voice in the national media—stories like the one you’ve just read.

Each day, our journalism cuts through lies and distortions, contextualizes the developments reshaping politics around the globe, and advances progressive ideas that oxygenate our movements and instigate change in the halls of power.

This independent journalism is only possible with the support of our readers. If you want to see more urgent coverage like this, please donate to The Nation today.

More from The Nation

Bad Bunny's Stunning Redefinition of "America" Bad Bunny's Stunning Redefinition of "America"

His joyous, internationalist, worker-centered vision was a declaration of war against Trumpism.

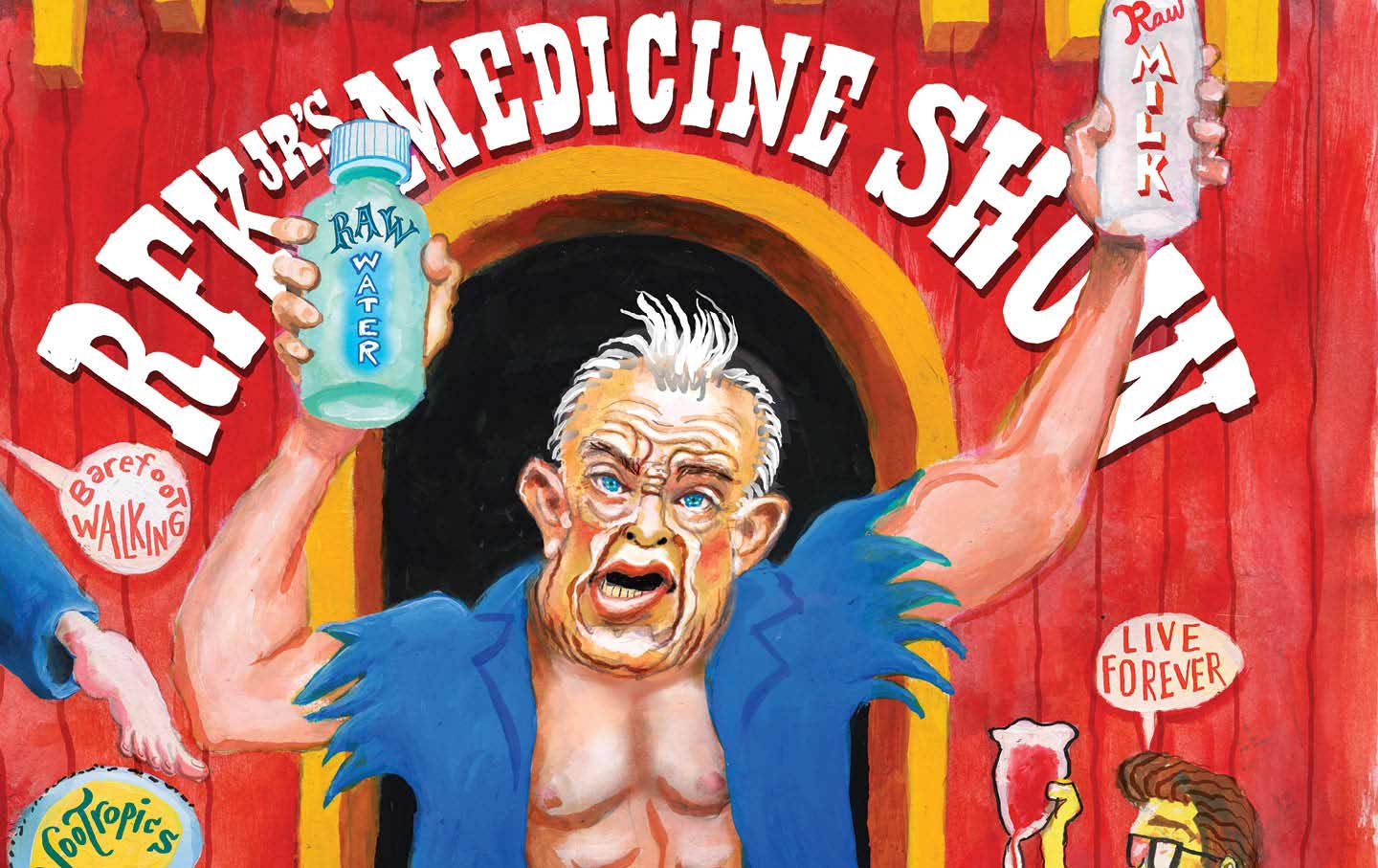

How the Far Right Won the Food Wars How the Far Right Won the Food Wars

RFK’s MAHA spectacle offers an object lesson in how the left cedes fertile political territory.

What the Pro-Choice Movement Can Learn From Those Who Overturned “Roe” What the Pro-Choice Movement Can Learn From Those Who Overturned “Roe”

The anti-abortion movement was methodical and radical at the same time. The abortion-rights movement must be too.

“Shut Up and Serve”: The Professional Tennis Players Fighting a Rigged System “Shut Up and Serve”: The Professional Tennis Players Fighting a Rigged System

An antitrust lawsuit calls the professional tennis governing bodies “cartels” that exploit players and create an intentional lack of competitive alternatives. Can players hit back...

The Real Harm of Deepfakes The Real Harm of Deepfakes

AI porn is what happens when technology liberates misogyny from social constraints.

How Stephen Miller Became the Power Behind the Throne How Stephen Miller Became the Power Behind the Throne

Miller was not elected. Nor are he or his policies popular. Yet he continues to hold uncommon sway in the administration.