The Cartoonist, the Director, and the Sex Workers

Sook-Yin Lee’s new romantic comedy, Paying for It, explores Platonic love and prostitution.

Some couples have a strange way of drawing closer together after they break up. That’s certainly the case with two Canadian artists, musician and filmmaker Sook-Yin Lee and cartoonist Chester Brown. Technically, they only dated from 1992 to 1996, a few years before I got to know them. But in a quarter century of our friendship, it’s been difficult for me to disentangle them from each other. They are ex-lovers, yes, but that doesn’t quite capture their bond. I’d often see them at the same social events. If I met them separately they’d be full of news and updates about the other. The exact nature of their relationship was hard to pin down and a frequent source of conversation among mutual friends.

Now the mystery of their coupledom is much easier to understand, thanks to Lee’s new semi-autobiographical movie Paying For It, which is adapted from Brown’s 2011 graphic memoir of the same title.

Paying For It is a quirky romantic comedy based on what might seem like unpromising material. Brown’s memoir is an account of how his split with Lee led him to abandon the idea of romantic love and become a habitual purchaser of sex. The book carries the subtitle “A comic-strip memoir of being a john.”

Brown’s road from boyfriend to john took place over several years. After the 1996 break-up, Brown and Lee continued to live together in what they optimistically or naïvely described as an open relationship. But while Lee dated other men, Brown was celibate. Hearing Lee argue with one of her boyfriends deepened Brown’s disenchantment with the idea of being in a relationship, which he came to see as upholding an impossible ideal of perpetual passion and toxically linked to unsavory emotions such as possessiveness.

Brown purchased sex for the first time in 1999 and, since then, has been a proud john. As a memoir, Paying For It is revelatory and unsettling. The sex is presented clinically and coldly, often from a birds-eye view at some distance. From his stark narrative, we can both see how being a john benefited Brown, making an introspective and awkward man more comfortable in his body. But Brown doesn’t flinch from describing alienating incidents. I remain haunted by his story of an appointment with a sex worker where they only realized after the fact that they had previously had sex before. Perhaps unintentionally, Brown reinforces the effect of estrangement by not depicting the faces of sex workers, a visual practice justified as a way of preserving privacy.

Interspersed with the accounts of paying for sex, Brown’s book features conversations he has with friends (including fellow cartoonists Seth and Joe Matt as well as Lee) who are puzzled by his lifestyle. These exchanges often resemble Socratic dialogues, with Brown fending off objections and doubts while offering his own libertarian defense of both decriminalizing sex work and (more controversially) abandoning romantic love.

Brown’s life takes an unexpected turn in 2003 when he starts hiring a sex worker he calls “Denise.” He becomes attached to her, feeling emotions he can only describe as “love.” Denise doesn’t profess love for Brown but says she cares for him. Over time, he becomes her only client. They remain together to this day in a monogamous sex-for-pay relationship that has both a financial and emotional connection.

The book Paying For It is a fascinating human document, even if it is not fully convincing as a polemic (in part because Brown’s own relationship with Denise undermines some of his arguments against romantic love).

Lee’s movie both adapts Brown’s “comic-strip memoir” and builds on it, giving the story emotional expressiveness that the cartoonist deliberately avoided in his recounting. What Lee adds to the story is her own parallel experiences dating men.

In the book, Lee is the impetus for action at the start, but then becomes an argumentative foil. In the movie, Brown’s autobiography mixes with Lee’s autofiction. Chester Brown remains Chester Brown (played by Dan Beirne, whose moon-faced shyness calls to mind the young Paul Dano), but Lee is reimagined as Sonny Lee (played by Emily Le as an exuberant, mercurial media personality). As Chester navigates through the world of brothels and sex work, Sonny has her own rocky adventures in the world of dating. One boyfriend cheats on her, another is emotionally abusive, and a third falls in love with someone else.

The movie is set in an accurately depicted grungy art world of downtown Toronto, a homey bohemia where basement apartments are furnished with futons and bookshelves made of crates. It’s a world where normative heterosexual marriage has given way to a plurality of relationships. In exploring this world, Lee has reinvented the romantic comedy.

Aside from Chester the john and Sonny the hapless dater, we’re given a spectrum of other attachments: the lesbian parenthood of Sonny’s friend Suzo Jones (a brisk, no-nonsense Noah Lamanna), the rivalrous and sarcastic artistic camaraderie of Chester’s cartoonist friends (variations of real Canadian cartoonists played by Chris Sandiford, Ely Henry, and Rebecca Applebaum), and even the comforting shared love that Chester and Sonny have for their pet dog, Mo. The movie is a celebration of the diverse forms love can take.

Throughout the movie we see variations of the iconic image of an intertwined, naked couple seen from above—an ideal that the movie insists can take many forms.

There are two interlinked romances in the film. One is Chester falling in love with sex worker Denise. The strength of this storyline owes much to Andrea Werhun’s magnetically embodied performance as Denise. Werhun is a former escort as well as an actor, and she brings to the role a jaunty confidence. (Some of the other actors in the film also have experience as sex workers.)

But the Chester/Denise love story is paralleled by the Chester/Sonny love story. Even as they stop being a couple and eventually move into separate residences, Chester and Sonny have an emotional bond that only tightens with time. At one point, Sonny tells Chester, “You know, for a man dead set against romantic love, you’re the most romantic man in the world.” Knowing the real-life Chester Brown, I have to confess that this line rang true to me. I’ve often been struck by the fact that he speaks more warmly and caringly about Denise and Sook-Yin (both of whom he has eccentric relationships with) than many men do about their more conventional partners.

The off-kilter narrative of the movie Paying For It calls to mind an argument about a subgenre of romantic comedy that the late philosopher Stanley Cavell developed in his book Pursuits of Happiness (1981). Cavell identified a series of Hollywood films made between 1934 and 1941 that he characterized as the subgenre of “the comedy of remarriage.” One prime example of the genre is Howard Hawks’s His Girl Friday (1940). Developed to evade censorship, comedies of remarriage tell stories of couples who rediscover their love, sometimes even after a divorce or other splintering events.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →In Paying For It, the remarriage is twice told: Chester’s relationship with Denise is a kind of outlaw marriage, as is his Platonic friendship with Sonny. With Denise, what starts off as a transactional relationship turns out to be a marriage in disguise, and with Sonny, what starts off as a break-up is revealed to be a continuing marriage. Though less frantic than the comedies of remarriage of the 1930s and ’40s, Paying For It brings to the genre a wistful, wry charm.

Paying For It is very much a film made by a couple. It’s not just that Lee adapted Brown’s book. Brown also drew the interstitial comic-strip art and makes a cameo appearance in the movie. Because of its collaborative nature, the best way to see the film (as the comics critic Heidi MacDonald has noted) is when it is combined with a panel featuring both the director and cartoonist.

Paying For It will make its US premiere at the Quad on January 30 and play on the 31 and February 1. Sook-Yin Lee and Chester Brown will speak at all three events. The film will also play at Laemmle Theatres in Los Angeles on February 3 and 4, again with the creators speaking. A full list of US screenings and events can be found here.

More from The Nation

Healthcare Workers Must Continue Alex Pretti’s Fight Healthcare Workers Must Continue Alex Pretti’s Fight

Pretti was one of us. We have to carry on his struggle.

How Online Frat Mobs Target Sexual Assault Survivors How Online Frat Mobs Target Sexual Assault Survivors

A video documenting an alleged gang rape in Florida drew a flood of harassment, threats, and doxxing

Should We Treat Political Violence as a Public Health Crisis? Should We Treat Political Violence as a Public Health Crisis?

Thinking of political violence solely as a safety issue is not enough to address the harm that follows. “The patient is the community.”

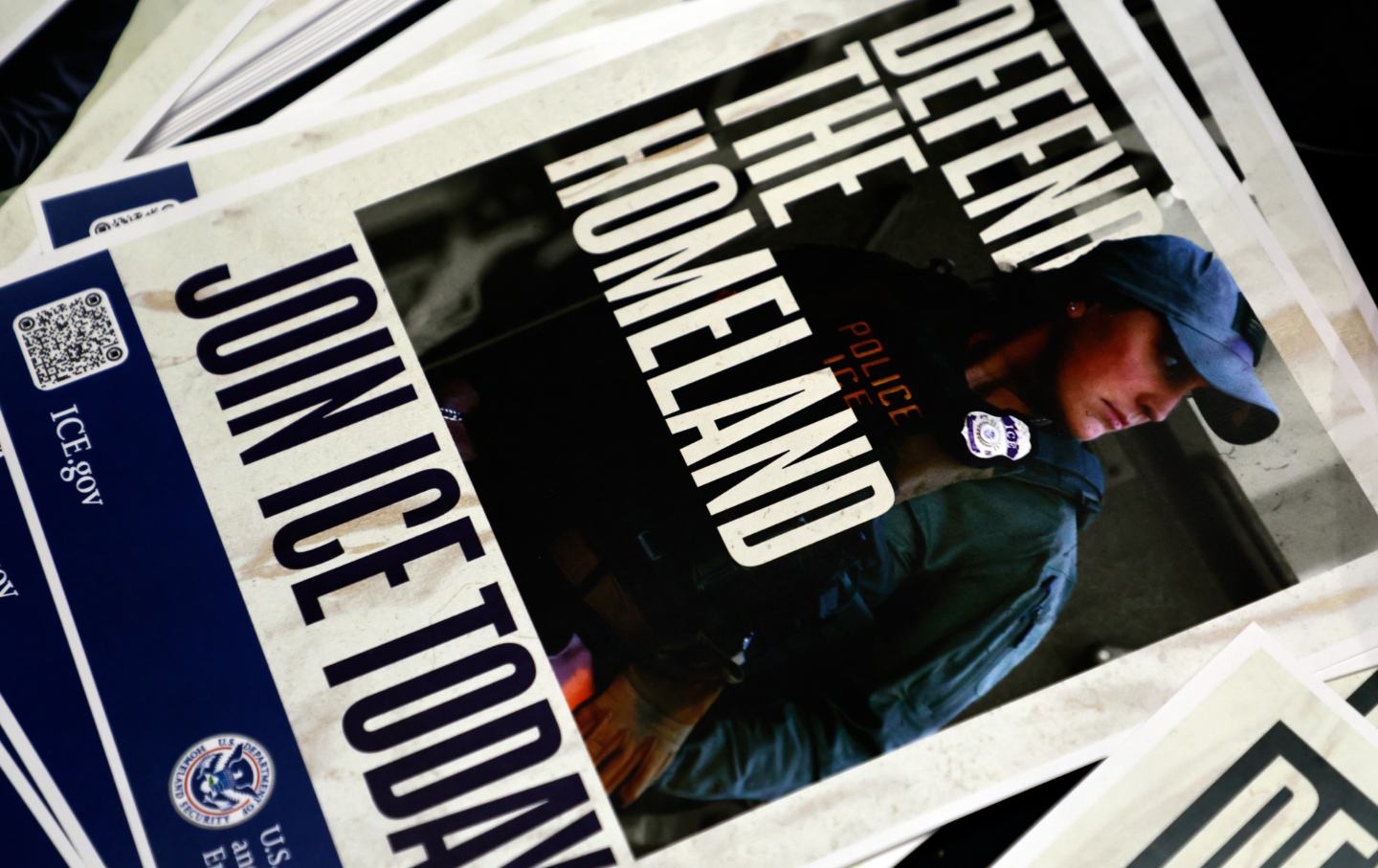

ICE’s Terror Campaign Is Part of a Long American Tradition ICE’s Terror Campaign Is Part of a Long American Tradition

As a Black man, I know firsthand how often state violence is used to perpetuate white supremacy in this country.

Whom Is ICE Actually Recruiting? Whom Is ICE Actually Recruiting?

ICE has lowered standards to facilitate a massive hiring spree. Many of the new recruits are plainly unqualified. Are some also white supremacists or domestic terrorists?

A Call Is Rising for Nations to Boycott the Trump World Cup A Call Is Rising for Nations to Boycott the Trump World Cup

As marauding state agents fill US streets, a leading German soccer official says countries should consider what was once unthinkable: skipping the 2026 World Cup.