How Online Frat Mobs Target Sexual Assault Survivors

A video documenting an alleged gang rape in Florida drew a flood of harassment, threats, and doxxing

In November, a University of Florida student, Maddie Kowalski, was allegedly gang raped while intoxicated at a fraternity gathering. The alleged assault was recorded without her consent and circulated at both the University of Florida and Florida State University on YikYak, an anonymous forum with dedicated pages exclusive to college campuses. Within days, the footage went viral across mainstream social media platforms—where users derided the victim, ignored the horrifying context of the video, and turned freeze-frame images of the attack on Kowalski into sensationalized memes. Malicious Web users also doxed members of Kowalski’s family, releasing their personal information into the world to be exploited by other bad actors on the Web.

On December 19, Kowalski posted a series of videos on Instagram, drawing tens of millions of views. In these posts, she sought to restore vital context and background to the trauma of her abuse—describing the conditions of the assault, detailing her inebriated state, and emphasizing that it wasn’t possible for her to consent to sex. Almost immediately, her comment sections were flooded with a disturbingly coordinated pattern of harassment. Fraternity-affiliated accounts tagged fellow brothers and other digital onlookers, joking about the number of alleged assailants, and volunteering to join the mob.

Other commenters continued targeting members of Kowalski’s family. Gossip columnist Marukho Pfozhe released a tabloid-style piece in The Sports Grail publicizing information about them—including the LinkedIn account for Kowalski’s father, along with a series of crude memes about her family. A gag account, @Therealjohnhog, wrote in a tweet attacking both her parents, “Just received a call informing me that Maddie Kowalski’s mom was in DZ at UF. And I swear to god her nickname was the ‘easy DZ.’ Someone please keep an eye on [Mr.] Kowalski.”

The profiles of many of these commenters revealed that they were not anonymous, temporary users shielding their identities behind “burner accounts” to harass Kowalski with impunity. Their comments were tagged with their full names on display, together in many cases with their university and fraternity affiliations. They left sexually suggestive comments like “me next,” and tagged another man to suggest that they should engage in group sex, making sport of Kowalski’s victimization at the hands of a predatory frat mob. The growing chorus of harassers ranged from fellow fraternity members to younger brothers. For them, the footage documenting a mass sexual assault was fodder for more abusive misogynist rhetoric—and vile jokes shared thousands of times among their peer group.

This isn’t the first time that Florida-based fraternities fomented a digital dog-pile following a woman’s claims of abuse. In December 2012, Erica Kinsman, a Florida State University student and member of the Delta Zeta sorority on campus, alleged that she was drugged, transported to an apartment, and raped by another student. Her alleged assailant was later identified as FSU’s star quarterback Jameis Winston, who would go on to win the 2013 Heisman trophy and be the number-one pick in the 2015 NFL draft. Football fans revered Winston, who has since been accused of sexually assaulting an Arizona Uber driver in 2016.

Florida State fraternities were early and vocal defenders of Winston. In the wake of Kinsman’s charges, a reporter for Tampa Bay Times surveyed the strong pro-Winston sentiments on the school’s Greek Row: “On College Avenue, standing in front of fraternities three hours before kickoff, male students…were unified in their support.” Just a month after Kinsman’s alleged assault, a viral video featured Winston tossing footballs at the university’s Pi Kappa Alpha chapter.

As Kinsman’s case awaited administration attention at the school, she became the subject of persistent memes and jeers on X (then Twitter). One user, @steevesauce, wrote in a series of malicious posts, “What does #EricaKinsman Dad feel like right now?”—anticipating the torrent of attacks that Kowalski’s family would later face. Vicious taunts like these extend the perverse logic of victim-blaming to the survivor’s wider family, implying that her parents raised a sexually licentious child who is ultimately responsible for her own assault.

For Kinsman, this pattern of abuse festered over many months. FSU chose to delay Winston’s Title IX hearing addressing Kinsman’s charges for nearly two years—a tactic that allowed him to continue playing for the FSU football team, in defiance of the Department of Education’s recommendations at the time that any accusation of sexual violence be investigated and resolved within 60 days. In 2014, Winston was found “not responsible.”

In Kinsman’s case, the university wound up indirectly abetting the concerted online abuse of an alleged sexual assault victim by dragging out an investigation; in Kowalski’s, the fraternity system so integral to social life at major state universities played an immediate and toxic role in denigrating the victim. But both episodes underline a broader structural obstacle for claims of abuse to receive the serious and sustained hearing they should merit at the institutions where the abuse has occurred: Networks of official neglect and peer-orchestrated escalations of abuse work in many cases to dismiss, downplay, and discredit the reports of survivors.

Kowalski’s case is emblematic of how the experience of a solitary victim was swamped with malicious commentary from a nationwide social system devised to conceal wrongs committed by people in and around its ingroup. Fraternities are dense, loyalty-driven networks constructed on promises of exclusivity and mutual protection. Long before social media, fraternity chapters cultivated an internal culture of secrecy and silence that has worked to shield members from accountability when harm is named.

Digital platforms are not responsible for creating this dynamic, but they have greatly accelerated the abusive conduct it generates. Today, in-group pride is continuously reinforced online through small acts of representation: Greek letters listed in bios and ritualized posts celebrating “brothers” or “sweethearts” of the week. These are innocuous online badges of belonging, but the ethos behind them can be readily weaponized against critics, accusers, or anyone perceived as a threat to the Greek world’s jealously guarded sense of cohesion.

The fiercely tribal cast of campus fraternity life predates the rise of social media by at least a century. In 1914, reports documented the far-reaching influence of what became known as the Alabama Machine—a coalition of University of Alabama fraternities that leveraged its power to shape the school’s student government and the outcomes of Tuscaloosa school board elections.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →More commonly, though, the power and exclusivity of Greek institutions on campus target individual women who could harm the reputations and legal standing of fraternities where alleged assaults occurred. This behavior is so normalized that some fraternities are colloquially referred to by nicknames like “Sexual Assault Expected” (Sigma Alpha Epilson), “Pike Spike” (Pi Kappa Alpha), or “The Rape Factory” (Psi Upsilon).

In many ways, this reflexive defense of male sexual impunity has furnished the template for a misogynist culture of digital abuse that has steadily gained momentum over the past two decades. Well before terms like “cancel culture” entered the mainstream, women speaking out against patterns of abuse online found themselves subjected to coordinated, sexualized abuse online.

In 2008, Anna Mayer, a young woman preparing to matriculate to graduate school, watched her pseudonymous blog documenting her struggles with weight stripped of all anonymity; her inbox was flooded with messages from anonymous users, calling her a “stupid, ugly, fat whore.” The abuse quickly escalated. Mayer’s online harassers messaged her that they’d obtained her home address and leaked her personal information, and issued threats of rape and sexual violence. Over the next year, troll-created webpages emerged in droves with names like “Anna Mayer’s Fat Ass Chronicles” and “Anna Mayer Keeps Ho’Ing It Up.”

Mayer’s experience was an early instance of the kind of coordinated abuse that became notorious in the 2014 Gamergate scandal. In that digital pile-on, female game designer Zoe Quinn, who had criticized the misogynist content favored by the gaming industry, faced a torrent of cyber-attacks under the guise of loyalty to a “wronged” ex-boyfriend. As in Mayer’s experience, the intended lesson of Quinn’s treatment was unmistakable: prominent voices who dared dissent from the prevailing misogyny of online discourse would be met with ugly and unrelenting campaigns of collective punishment, up to and including the release of sensitive information to online mobs vowing to wreak chaos, sexual assault, and worse on the speakers in question.

Even fame and wealth afford no protections against this gendered culture of drive-by digital assault—as Johnny Depp’s ex-wife Amber Heard learned to her distress in 2022. Depp sued Heard for defamation in a Virginia court after she had published an op-ed in The Washington Post that referenced her experience of abuse without explicitly naming Depp as her abuser. The ensuing global online spectacle resembled nothing so much as the fraternity-based culture of collective punishment on steroids. Millions took to social media to misrepresent evidence, distort Heard’s testimony, and reduce both her allegations and personhood into monetizable memes. Just as we have seen with Kowalski in real-time, a woman’s account of harm became fodder for entertainment and crude, unempirical assaults on her character, while her credibility became collateral damage.

What’s different about Kowalski’s experience is primarily the speed and force that now propel online abuse campaigns forward. And with platforms such as Elon Musk’s X functioning as accelerants of all manner of sexual victimization, the sort of vindictive abuse that had formerly found traction on more marginal discussion boards such as 4Chan and Reddit has now gone mainstream.

TikTok, which is the platform of choice for younger commentators like the ones behind the Kowalski pile-on, operates on a heightened version of the standard social-media algorithm that prioritizes user engagement over everything else. On TikTok, every like, comment, share, or completed view is logged—and then determines the content across each user’s personal feed. The more the algorithm knows about you, the more precisely it can tailor content, the longer it can keep you scrolling, and the more opportunities it creates to monetize your screen time through advertising.

One tactic central to this process on short-form video platforms like TikTok and YikYak is the use of serendipity—i.e., the introduction of provocative content that seeks to further mine engagement for titillation and profit. It’s now common for users who are a few minutes into a typical scroll on TikTok, Instagram Reels, or YouTube Shorts to encounter a video that makes them double-check that they are logged in to the correct account. The content feels wildly off-base in comparison to the rest of users’ carefully curated timelines, as though the algorithm has made an obvious mistake. It hasn’t. It is testing whether this new topic might hold their attention just long enough to keep them scrolling further—and supplying additional data for their feeds to exploit.

Now imagine you have posted a video outlining the story of your assault on social media, and that video has serendipitously landed on the timelines of users who’ve been conditioned to unleash outrageous comments on vetted streams of content that tag their fraternity brothers, who pile on with explicit threats of rape. There is no attempt at anonymity, no dog whistle from a burner account—only open cruelty, normalized and amplified through the pervasive social mandate to dismiss harm inflicted on women.

It’s true, of course, that individual users are responsible for their own reactions and responses. However, it’s impossible to overlook the broader pattern at work here: an online escalation of age-old fraternity-based patterns of expansive male complicity in the abuse of women who name the harms they’ve suffered. A pattern of discourse that’s served repeatedly to enable the toxic and threat-fueled backlashes against Kowalski, Heard, Kinsman, Quinn, and Mayer is anything but random. To begin the hard work of dismantling this kind of deeply ingrained—indeed ritualistic—abuse, we need to clearly identify the systems that exploit and benefit from it.

The systems at fault here—Greek societies, universities, and the law—routinely decline to intervene and prevent future harm. We tend to group these non-responses under the heading of “institutional failure”—the effort to defend an institution’s reputation at the expense of someone who has been victimized within it. But this reflex confines us to scrutinizing institutions’ performance on a case-by-case basis, leaving the underlying patterns intact and ready to be unleashed on the next defenseless victim. We encounter a similar label ascribed to fraternity men: “toxic masculinity,” which suggests that individual bad actors are to blame, as opposed to a far more deeply rooted fraternity culture of exclusivity, collective defense, and impunity. These phrases have produced no net positive or sustained change.

Instead of telling these systems and young men that they are “failures” or “toxic,” we propose a new approach: tell them what they should aspire to become. Let them know why survivors should matter to them, and make them aware of how many survivors exist quietly within their administrative and social circles. The challenge posed by the weaponized online culture of misogyny and rape threats is to go beyond the grim logic of algorithmic fantasies of sexualized violence and to find genuine inspiration in affirming the humanity of women.

More from The Nation

The Cartoonist, the Director, and the Sex Workers The Cartoonist, the Director, and the Sex Workers

Sook-Yin Lee’s new romantic comedy, Paying for It, explores Platonic love and prostitution.

Should We Treat Political Violence as a Public Health Crisis? Should We Treat Political Violence as a Public Health Crisis?

Thinking of political violence solely as a safety issue is not enough to address the harm that follows. “The patient is the community.”

Healthcare Workers Must Continue Alex Pretti’s Fight Healthcare Workers Must Continue Alex Pretti’s Fight

Pretti was one of us. We have to carry on his struggle.

ICE’s Terror Campaign Is Part of a Long American Tradition ICE’s Terror Campaign Is Part of a Long American Tradition

As a Black man, I know firsthand how often state violence is used to perpetuate white supremacy in this country.

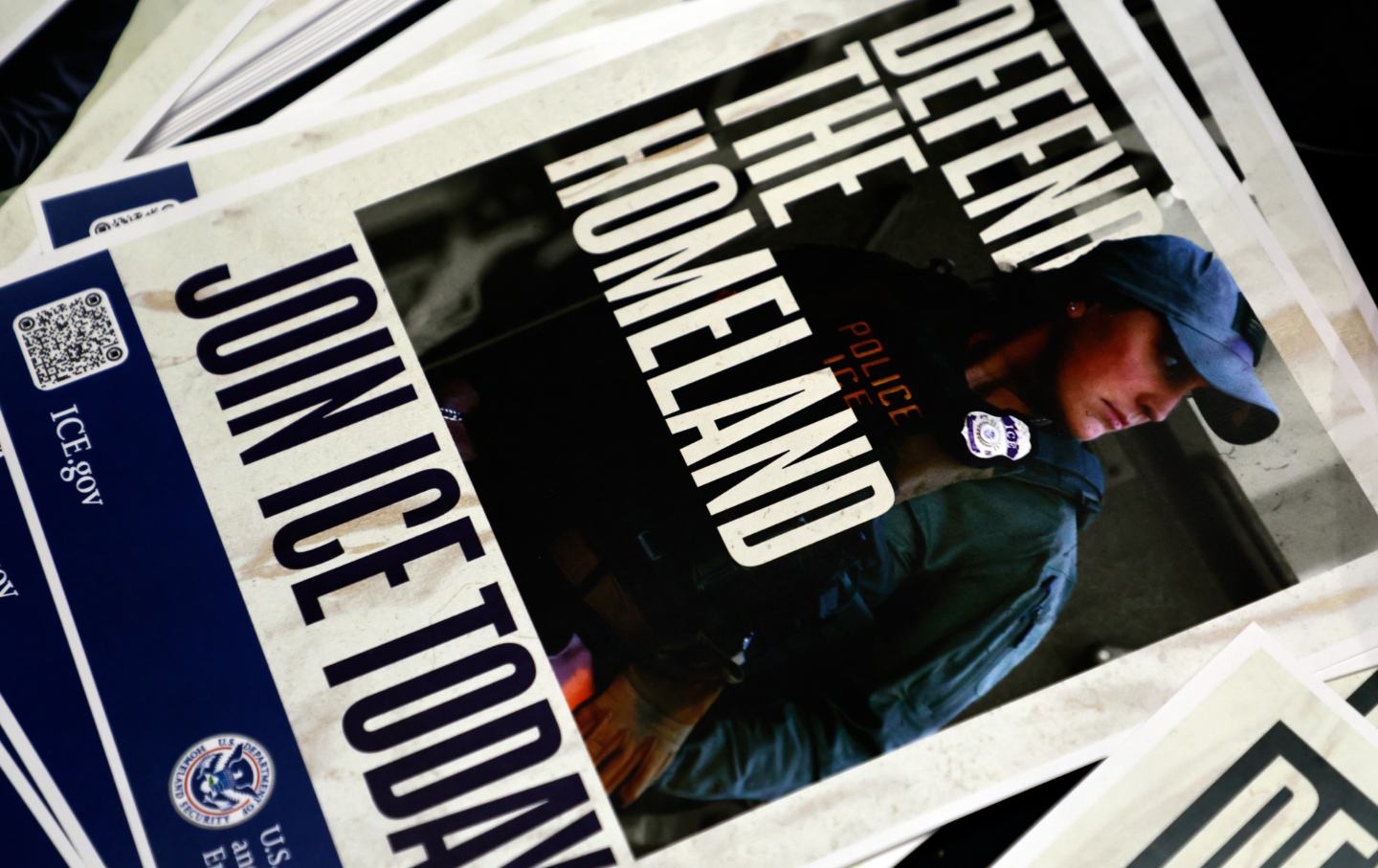

Whom Is ICE Actually Recruiting? Whom Is ICE Actually Recruiting?

ICE has lowered standards to facilitate a massive hiring spree. Many of the new recruits are plainly unqualified. Are some also white supremacists or domestic terrorists?

A Call Is Rising for Nations to Boycott the Trump World Cup A Call Is Rising for Nations to Boycott the Trump World Cup

As marauding state agents fill US streets, a leading German soccer official says countries should consider what was once unthinkable: skipping the 2026 World Cup.