How to Save the Amazon

Listen to the people who live there, the slain journalist Dom Phillips advised.

Dom Phillips, left.

(Courtesy of Nicoló Lanfranchi)

Dom Phillips and Bruno Pereira were murdered three years ago this month during a reporting trip for the book Phillips was writing, How to Save the Amazon. Jonathan Watts, Phillips’s colleague at The Guardian, and others who knew him have honored his memory by finishing his book about the vast South American rainforest vital to global climate stability. Below is an adaptation from the book

Dom left us with a big unanswered question: How Do We Save the Amazon? In an outline for the final chapter of his book, he wrote, “Listen to Indigenous People.” The world, he added, “is not a disconnected, random series of nations and societies, but an interconnected whole whose survival depends on cooperation, not competition.” To understand this, he argued, “the best teachers are the Amazon’s original inhabitants: its Indigenous peoples.”

Dom and Bruno spent the final day of their lives seeking lessons from those very teachers. Before writing this conclusion to the book Dom didn’t live to complete, I retraced their steps, venturing back to the Javari Valley where their friendship was first cemented.

Considering its location on the frontline of a deadly conflict, the Valley’s Lago do Jaburu feels a blessedly tranquil place. A couple of archetypal riverine homes, built on stilts, with wood-plank walls and corrugated roofs, are perched at the top of a steep bank above the Itaquaí river. Dom and Bruno had come here to join an Indigenous surveillance team that patrolled the border between the protected territory and its hinterlands.

In the morning and afternoon of that last day, Dom—as rigorous as ever—individually interviewed all 13 men on the surveillance team, asking them the same questions: How did they protect their territory, for whom were they protecting nature, in what way were they affected by the political situation?

The political situation in Brazil had changed a great deal after Jair Bolsonaro was elected president in 2019. In his first full year in power, Amazon deforestation hit the highest level in more than a decade. Brazil’s greenhouse gas emissions rose 12.2 percent from 2020 to 2021, the highest in 19 years. Meanwhile, there was a 38 percent decrease in the number of fines for environmental crimes. Bolsonaro’s far-right government was letting this happen, yet it not only denied responsibility, it noisily blamed others.

I learned about Dom’s interviews with the surveillance team partly by speaking with a member of that team, Higson Dias Kanamari, of the Kanamari people. Higson recalled his last encounter with Dom with a mix of affection and horror. ‘‘He was very happy to be among us Indigenous people,” he said. “When he was with us, he had a second family. We looked after him. I could see the pleasure he had from being with us. Unfortunately, we couldn’t anticipate the extent of the evil that people wanted to do.”

For weeks after Dom and Bruno’s deaths, the nearest town of Atalaia do Norte was flooded with reporters. Residents wryly noted that the intense coverage of the death of a white foreign journalist was in striking contrast with the murder three years earlier of FUNAI officer Maxciel Pereira dos Santos, who had worked closely with Bruno in tracing illegal fishing and hunting operations. Maxciel’s family believes the assassination was carried out by the same people who killed Bruno and Dom. But nobody was ever charged, and the case barely made a ripple outside the region.

As well as the double standards, Higson said the treatment of the two crimes showed the power of stories that can attract a global audience. “When they killed Maxciel, nothing happened. But with Dom and Bruno, there was an enormous interest.” He saw this as a positive: “The media was the focal point for the world to learn about the defenders of the forest.”

Dom was an unusual Amazon martyr in being white and from a rich nation. Most of the others were Indigenous, quilombolas, ribeirinhos—victims of murders that were never investigated or covered by the media, people whose names and faces were largely unknown outside their hometowns. It is a similar story across the world, where more than 1,900 people have been murdered since 2012 trying to protect their land and resources. That’s an average of one killing every two days.

I wonder how Dom would have written about the post-Bolsonaro years. Since he and Bruno died, there have been a few positive signs of change. In 2023, the Workers’ Party president Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva promised zero deforestation by the end of the decade, appointed Brazil’s first Indigenous minister, Sonia Guajajara, recognized more than half a dozen new Indigenous territories, initiated moves toward a bioeconomy, and saw his environment minister, the Amazonian Marina Silva, delay approval for oil exploration near the mouth of the Amazon river and a new license for the Belo Monte hydroelectric dam.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →This was progress, though it was uneven and not nearly enough. Indigenous groups in the Javari Valley said they saw no improvement on the ground. Elsewhere, some problems became worse. The agribusiness-dominated Congress moved to limit future land demarcations and tried to push forward new megaprojects, including a major upgrade of the BR-319 highway through one of the last pristine areas of rainforest.

It is a reminder, if one were needed, that government-led command-and-control politics are important but limited. Deforestation has been cut by an impressive 50 percent, but this merely slowed the destruction. The Amazon is still moving ever closer to a tipping point.

If the forest and its people are to resist this and maintain their diversity, independence, and traditional culture, a more profound transformation is needed. The core Amazon battle is for hearts and minds. Sure, defending territory on the ground was a crucial first step. Securing government support could then slow destruction. Bringing transparency to beef and soy supply chains would help too. As would a rethink about destructive infrastructure projects. Valuing forests more alive than dead would be a game changer. Securing international finance should accelerate the transition to a sustainable future. Ecotourism and carbon taxes might have a role to play. Compelling global pharmaceutical companies to share the benefits of biodiversity would incentivize conservation and support livelihoods.

But for all of these ideas to work, what matters most is a healthier way of thinking about the forest. It is about listening, about building a new relationship with nature. Or, better still, rediscovering the virtues of an old one. That does not need to be complicated. It can be instinctive. It can be the feeling of delight in seeing the world as it should be. It can even start with the simple expression of joy Dom shared in the last social media post of his life: ¡Amazônia, sua linda!—Amazonia, you beauty!

Disobey authoritarians, support The Nation

Over the past year you’ve read Nation writers like Elie Mystal, Kaveh Akbar, John Nichols, Joan Walsh, Bryce Covert, Dave Zirin, Jeet Heer, Michael T. Klare, Katha Pollitt, Amy Littlefield, Gregg Gonsalves, and Sasha Abramsky take on the Trump family’s corruption, set the record straight about Robert F. Kennedy Jr.’s catastrophic Make America Healthy Again movement, survey the fallout and human cost of the DOGE wrecking ball, anticipate the Supreme Court’s dangerous antidemocratic rulings, and amplify successful tactics of resistance on the streets and in Congress.

We publish these stories because when members of our communities are being abducted, household debt is climbing, and AI data centers are causing water and electricity shortages, we have a duty as journalists to do all we can to inform the public.

In 2026, our aim is to do more than ever before—but we need your support to make that happen.

Through December 31, a generous donor will match all donations up to $75,000. That means that your contribution will be doubled, dollar for dollar. If we hit the full match, we’ll be starting 2026 with $150,000 to invest in the stories that impact real people’s lives—the kinds of stories that billionaire-owned, corporate-backed outlets aren’t covering.

With your support, our team will publish major stories that the president and his allies won’t want you to read. We’ll cover the emerging military-tech industrial complex and matters of war, peace, and surveillance, as well as the affordability crisis, hunger, housing, healthcare, the environment, attacks on reproductive rights, and much more. At the same time, we’ll imagine alternatives to Trumpian rule and uplift efforts to create a better world, here and now.

While your gift has twice the impact, I’m asking you to support The Nation with a donation today. You’ll empower the journalists, editors, and fact-checkers best equipped to hold this authoritarian administration to account.

I hope you won’t miss this moment—donate to The Nation today.

Onward,

Katrina vanden Heuvel

Editor and publisher, The Nation

More from The Nation

The Fight for the Last Wild Salmon The Fight for the Last Wild Salmon

In Alaska, the last stronghold for wild salmon, Native tribes and conservationists are working to save the fish from both climate change and decades of corporate greed.

What Your Cheap Clothes Cost the Planet What Your Cheap Clothes Cost the Planet

A global supply chain built for speed is leaving behind waste, toxins, and a trail of environmental wreckage.

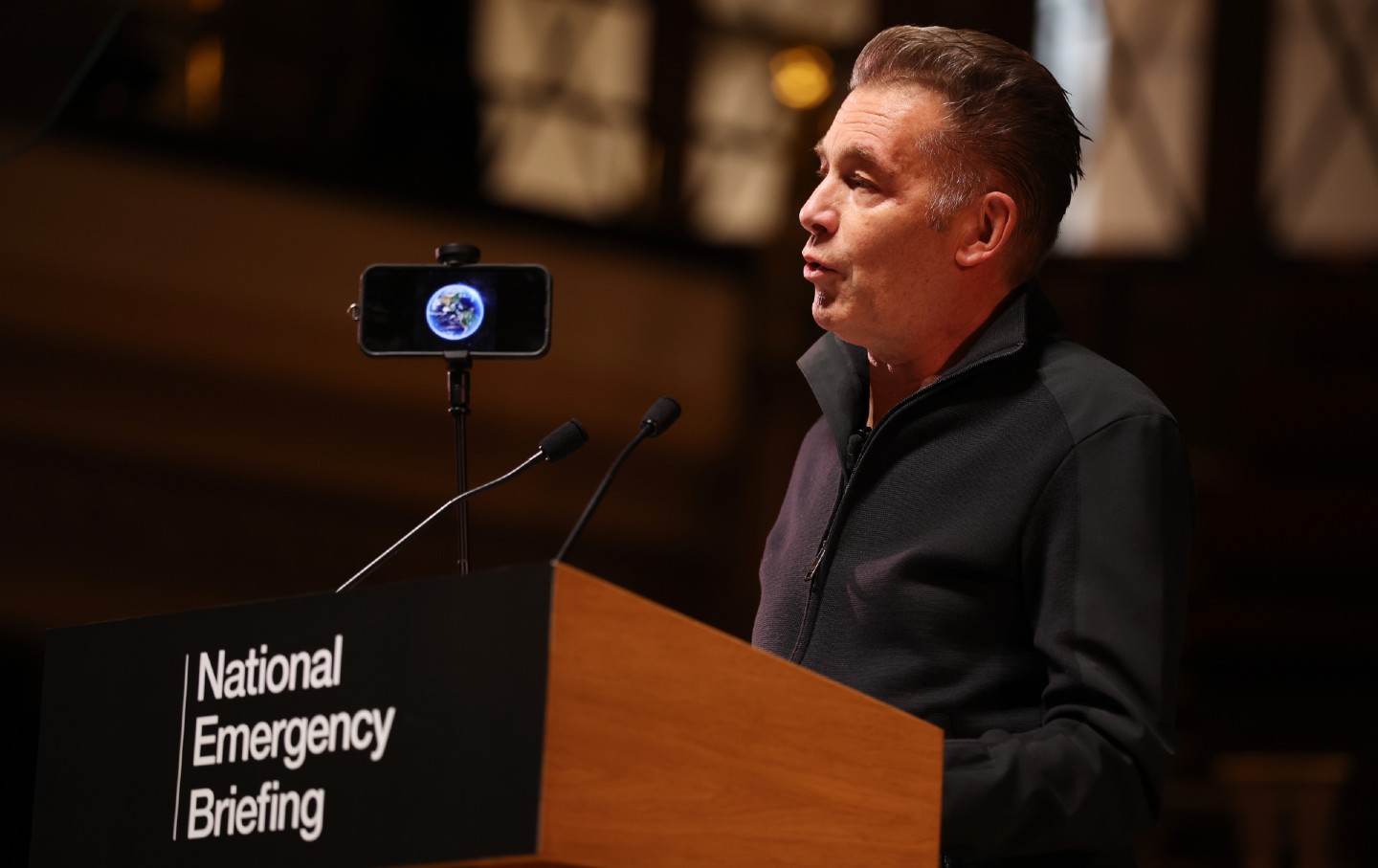

The UK’s Climate National Emergency Briefing Should Be a Wake-Up Call to Everyone The UK’s Climate National Emergency Briefing Should Be a Wake-Up Call to Everyone

The briefing was a rare coordinated effort to make sure the media reflects the science: Humanity’s planetary house is on fire, but we have the tools to put that fire out.

AI Will Only Intensify Climate Change. The Tech Moguls Don’t Care. AI Will Only Intensify Climate Change. The Tech Moguls Don’t Care.

The AI phenomenon may functionally print money for tech billionaires, at least for the time being, but it comes with a gargantuan environmental cost.

Backsliding in Belém Backsliding in Belém

Petrostates at COP30 quash fossil fuel and deforestation phaseouts.

Wake Up and Smell the Oil. Your Nation’s Military Is Hiding Its Pollution From You. Wake Up and Smell the Oil. Your Nation’s Military Is Hiding Its Pollution From You.

A fact all but ignored at COP30.