Ukraine’s War on Its Unions

Since the start of the war, the Ukrainian government has been cracking down harder on unions and workers’ rights. But slowly, the public mood is shifting.

On June 5, shortly after ten in the morning, black-clad officers stormed into the House of Trade Unions. The symbolic building on the Maidan, Kyiv’s Independence Square, is the headquarters of the country’s largest trade union federation, the Federation of Trade Unions of Ukraine (FPU).

The roughly 30 officers ordered the union employees to pack their things. The House of Trade Unions, they stated, has been confiscated. Employees and journalists were stopped outside, prevented from entering the building—by force if necessary.

The president of Profbud, an FPU member union representing the rights of workers in the construction industry, Vasyl Andreyev, speaks of a completely new level of escalation. Despite the government’s aggressive campaign against trade unions, this step came as a surprise to everyone, he recalls. Until that day, Profbud also had its offices in the House of Trade Unions.

Behind the operation was the Asset Recovery and Management Agency (ARMA), a state body responsible for securing and managing assets linked to corruption. In tow that day were heavily armed security forces and the new private property management company selected by ARMA.

The raid was not an isolated incident but part of a deepening confrontation between the government and the country’s unions. International union federations criticized that the seizure was part of a broader pattern of repression, including intimidation, criminal investigations, and legislative attacks.

ARMA justified its action with corruption allegations. Between 2016 and 2018, union officials had allegedly embezzled FPU real estate and personally profited from it. On this basis, the agency seized not only the House of Trade Unions but also numerous other FPU buildings. In April, law enforcement authorities arrested the FPU president, Grygorii Osovyi, along with four other officials. Osovyi has been under house arrest ever since.

Vasyl Andreyev says he cannot comment on the ongoing proceedings. However, he is not aware of any evidence supporting the accusations. The FPU and numerous unions at home and abroad criticized the arrest as politically motivated. The aim, they argued, was to destabilize the country’s largest trade union federation. The general secretary of the International Trade Union Confederation, Luc Triangle, called for the immediate release of Grygorii Osovyi and the termination of all proceedings.

Even if there were some merit to the corruption allegations, labor lawyer Vitalii Dudin argues, the government’s approach is disproportionate. Dudin, a leading figure in Ukraine’s grassroots organization Sotsialnyi Rukh (Social Movement), adds: “Legal action against individuals cannot justify measures that affect an entire organization.” He also suspects political motives behind the escalation. “Our governing party is pursuing a clearly neoliberal course. Until now, our trade unions were the only ones seriously opposing it.”

With his party Sluha narodu (Servant of the People), Volodymyr Zelensky achieved an unprecedented election victory in 2019. His faction holds nearly 60 percent of the seats in the Verkhovna Rada, Ukraine’s parliament. Well before Russia’s full-scale invasion, the government repeatedly sought to reform labor legislation in ways that favored employers. Each time, it was forced to backpedal due to large protests led by the unions.

The situation changed fundamentally with the outbreak of war. Martial law allows neither demonstrations nor strikes. Many union members are fighting at the front or living in exile. “The government did not create this situation, but it has undoubtedly taken advantage of it,” Dudin says.

In March 2022, just weeks after the war began, parliament adopted the first reforms of labor and trade union law—among them the very neoliberal bills that had previously failed time and again due to union resistance.

The new regulations make it easier to dismiss employees, raise the maximum weekly working time from 40 to 60 hours, and allow weekend shifts without extra pay. While some emergency measures can be explained by wartime conditions, Dudin argues that many go far beyond what the situation requires. „They weaken the role of collective agreements and collective bargaining. This is the 101 of market liberalization.”

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →Further “reforms” followed. The government introduced so-called “zero-hour contracts”: on-call employment with pay only for hours worked. Although the law guarantees a minimum of 32 hours per month, lawyer Vitalii Dudin warns that the reform risks a two-tier workforce—secure contracts for compliant employees, precarious ones for union members.

The government’s “reform” frenzy is not over yet. Last year, the Ministry of Economy published a draft of a new labor code. It contains 329 articles that, according to the government, are intended to reduce bureaucracy and bring Ukraine closer to European standards. Critics see this as a further shift in the balance of power in favor of employers.

Without giving reasons, companies could decide on new working hours and wages within a week. Employees could be suspended without pay during ongoing dismissal negotiations. Trade unions would lose any say in operational decisions. “All of this,” says political economist Yuliya Yurchenko, senior lecturer at the University of Greenwich, “would not bring Ukrainian labor law closer to the EU, but instead move it further away as deregulation continues.”

However, after the initial shock at the start of the war, the unions have regained their footing. So far, they have successfully prevented the bill from being put to a vote in parliament. Observers suspect a direct link between the regained strength of the unions and the escalation of state repression. But Dudin speculates that the government underestimated how strong the headwinds of this escalation would be. Harsh criticism has come not only from international trade union alliances; dissatisfaction also seems to be growing among the population, he says.

On the sidelines of a summit in central Kyiv, which was actually meant to focus on Ukraine’s EU accession process, frustration erupted in early November. “How can EU accession be discussed here while trade union buildings are being seized?” one audience member asked. Another criticized the government’s reforms as neither progressive nor EU-compliant, but somewhere between “neoliberal and libertarian.” The invited Ukrainian MPs appeared visibly tense and failed to provide answers.

The invitation came from the Social Democratic Group in the European Parliament. In their speeches, several members of the European Parliament warned—without directly naming the attacks on trade unions—that the current course was leading in the wrong direction. Yuliya Yurchenko was also invited as one of the panelists and became far more explicit. If policy is geared solely towards the interests of companies and not workers, she asked, who will benefit from the promised progress?

We need policies for the majority—not just for oligarchs—that address reskilling and upskilling, childcare, flexible hours for parents, and affordable housing, Yurchenko tells The Nation. At the summit, she delivers a final, unmistakable rebuke: the government’s treatment of trade unions, she says, is authoritarian and absolutely unacceptable. “We are not Russia. We are Ukraine.”

The audience applauded, though most Ukrainian MPs had long since left the chamber. On the ground, the immediate tension had quietly eased by the time of the summit. The FPU has found a new headquarters, less than two kilometers from the Trade Union House. And since July, Serhiy Byzov has been the federation’s new president. The government knows it crossed a red line with the arrest of Grygorii Osovyi and the confiscation of the House of Trade Unions, Dudin says.

For several months, the government has taken a more conciliatory tone. At the celebrations marking the FPU’s 35th anniversary in October, several members of the governing party attended and publicly praised the union’s work. “After all the campaigns against the unions, it was a bizarre sight,” Dudin recalls.

According to parliamentary sources, the planned labor code is also not expected to be submitted to parliament—at least not this year. But Dudin does not believe in a genuine change of course. “They will try again. I have no doubt about that.”

More from The Nation

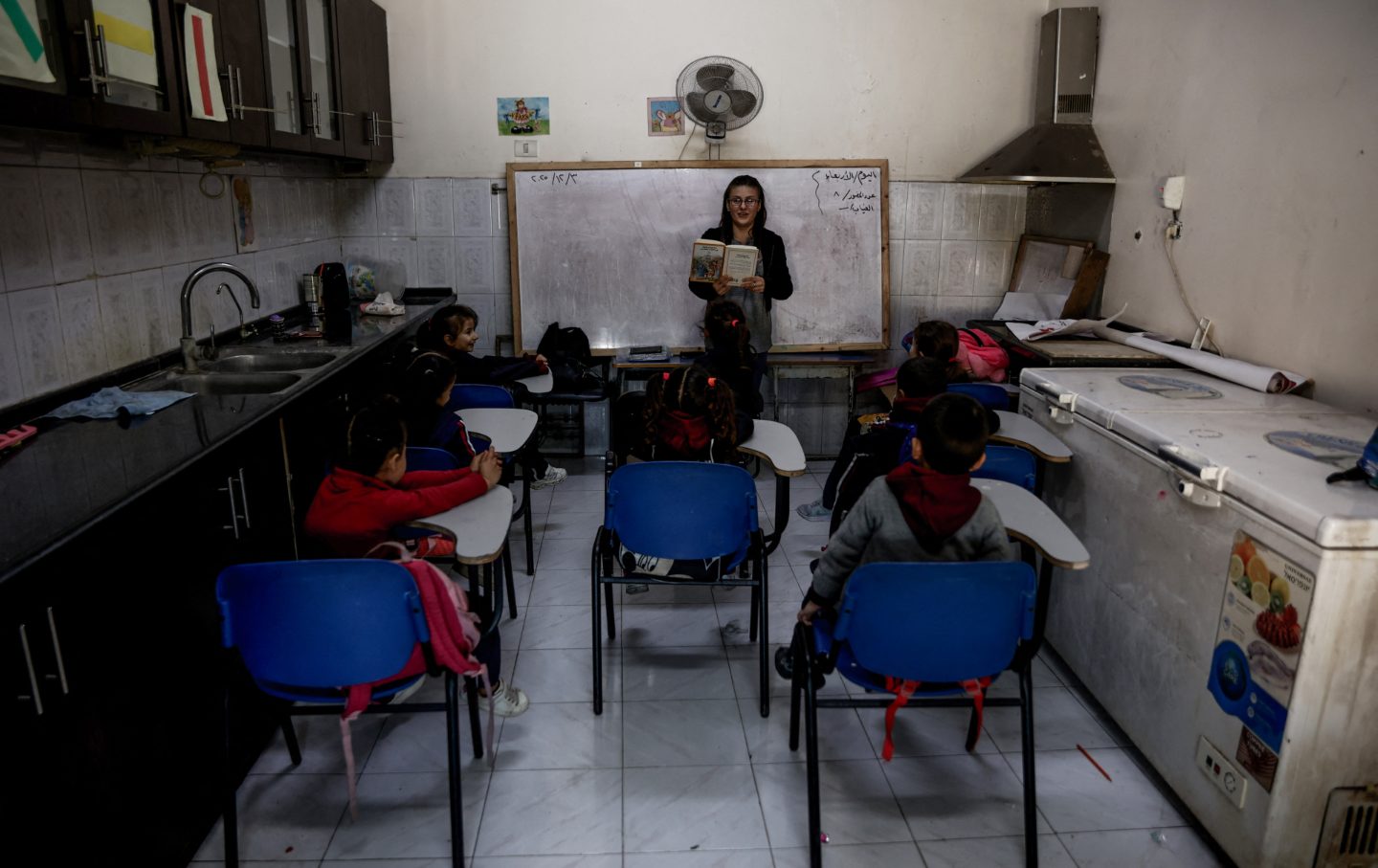

I’m a Teacher in Gaza. My Students Are Barely Hanging On. I’m a Teacher in Gaza. My Students Are Barely Hanging On.

Between grief, trauma, and years spent away from school, the children I teach are facing enormous challenges.

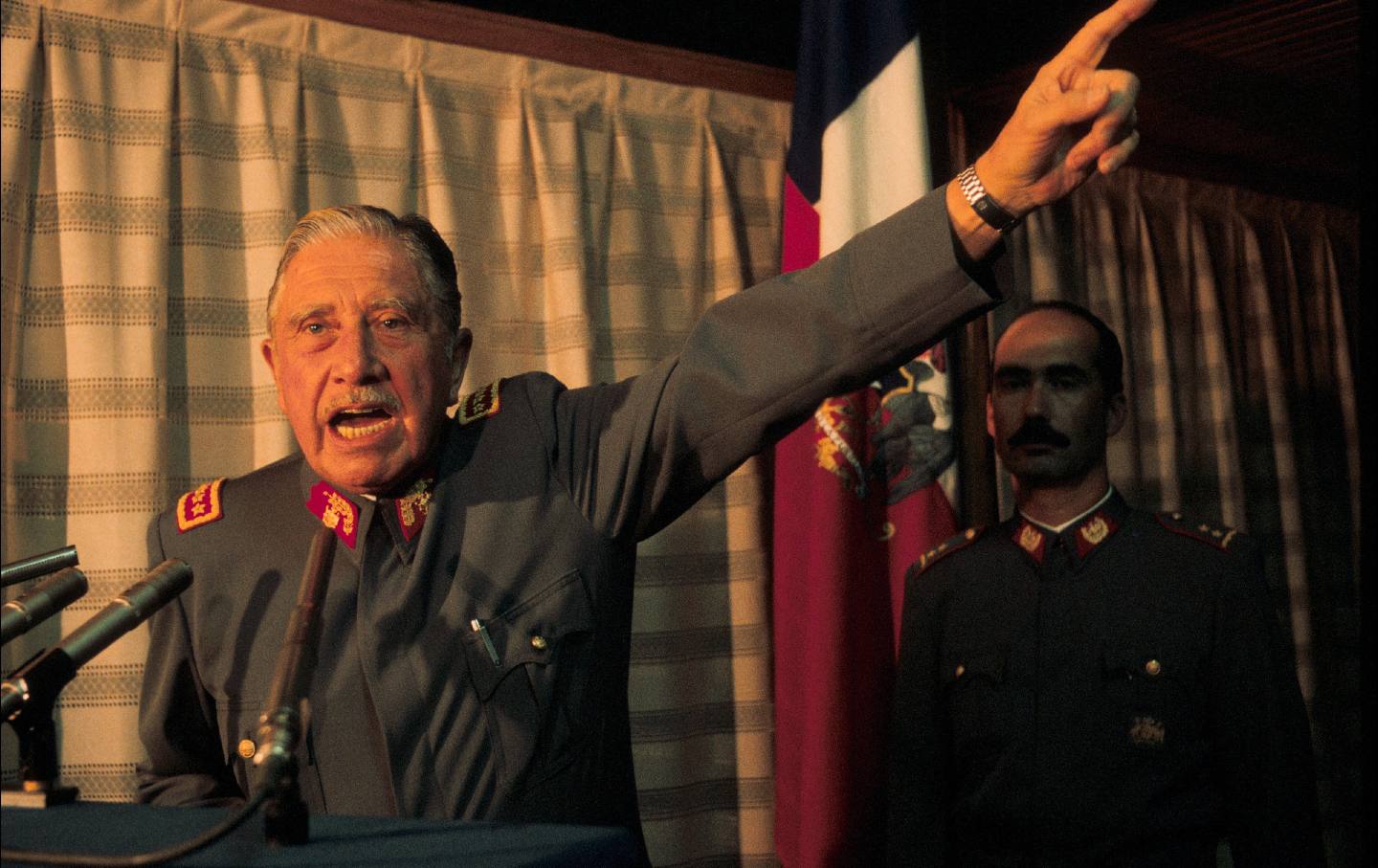

Operation Condor: A Network of Transnational Repression 50 Years Later Operation Condor: A Network of Transnational Repression 50 Years Later

How Condor launched a wave of cross-border assassinations and disappearances in Latin America.

The Gaza Genocide Has Not Ended. It Has Only Changed Its Form. The Gaza Genocide Has Not Ended. It Has Only Changed Its Form.

A real ceasefire would mean opening borders, rebuilding what was destroyed, and allowing life to return. But this is not happening.

How Trump Is Using Claims of Antisemitism to End Free Speech How Trump Is Using Claims of Antisemitism to End Free Speech

Trump’s urge to suppress free speech may be about Israel today, but count on one thing: It will be about something else tomorrow.

Will Technology Save Us From a Nuclear Attack? Will Technology Save Us From a Nuclear Attack?

So far, the Golden Dome seems more like a marketing concept designed to enrich arms contractors and burnish Trump’s image rather than a carefully thought-out defense program.

The Security Council’s Resolution on Gaza Makes Trump Its New Overlord The Security Council’s Resolution on Gaza Makes Trump Its New Overlord

The resolution is not only a possible violation of UN rules, it also makes the administration directly responsible for Palestinian oppression.