Free Boris Kagarlitsky

The Nation joins the global appeal for his release.

As people flooded Moscow’s streets March 1 protesting Aleksey Navalny’s death in an Arctic prison camp, the outpouring became a display of dissent at a time of growing repression. As the Russian Orthodox service unfolded in the working-class Marino district, where Navalny and his family lived for decades, other Russian antiwar dissidents are confronting a new and expanding wave of repression and arrests.

Perhaps in anticipation of Presidential elections slated for March 17 (no cliffhanger), the growing strength of nationalistic “siloviki,” or part of an attack on the Russian Left movement, Russian authorities are handing out harsher sentences to those who appeal their charges. Prominent Russian activist Oleg Orlov, a veteran human rights campaigner and a leader of the Memorial human rights organization that jointly won the Nobel Peace Prize in 2022, was initially fined $1,630 for an article “discrediting the armed forces.” When Orlov appealed the ruling, a Moscow Court sentenced him last month to two and a half years for opposing Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

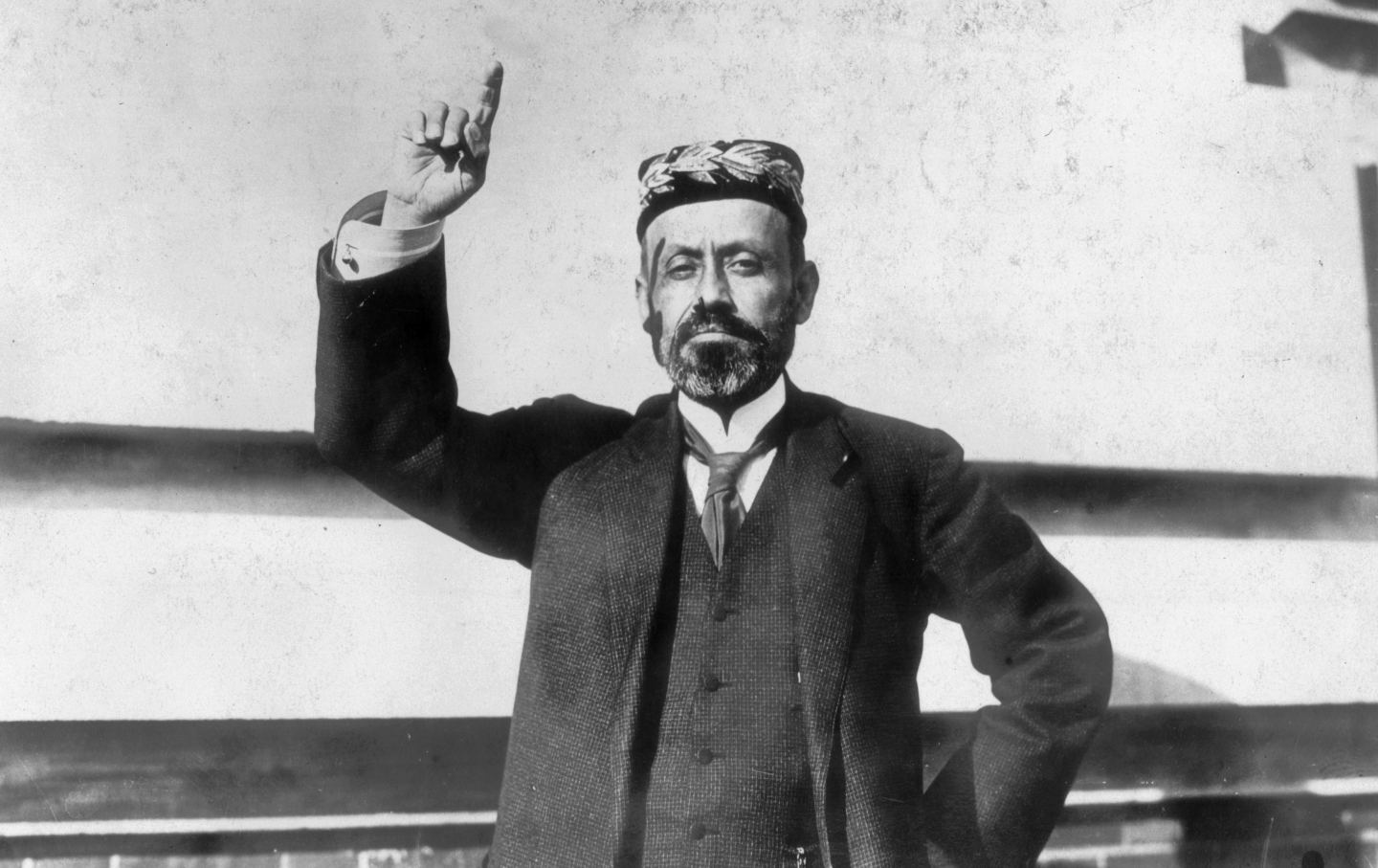

And on February 13, a military court sentenced Boris Kagarlitsky, prominent sociologist, Marxist scholar and labor activist, to five years in prison for criticizing the war in Ukraine. This was after a Moscow court initially ordered him to only pay a $6,500 fine for “justifying terrorism,” charges which Kagarlitsky denied. Prosecutors appealed the lower court’s decision to fine him, calling it “excessively lenient.” Kagarlitsky, the founder and chief editor of the left-labor news organization Rabkor, and director of the Institute of Globalization and Social Movements (which was labeled a “foreign agent” in 2018), was first detained in July 2023 in connection with a since-deleted YouTube video about the 2022 Crimea bridge explosion.

Perhaps because Boris has been arrested before as a dissident—in 1982 during the Brezhnev years and in 1993 when he protested Yeltsin’s shelling of the country’s elected Parliament—he responded to the decision with calm and dignity: “We just need to live a little longer and survive this dark period for our country.”

I met Boris Kagarltsky in Moscow in 1982. He was a research assistant to the Marxist dissident historian Roy Medvedev, author of On Socialist Democracy and Let History Judge. My late husband, Stephen Cohen, who was living in Moscow on IREX’s academic exchange in 1976, met with Medvedev—who lived far from the city’s center—every few weeks to exchange ideas and historical documents. Our visit was unusual because of Boris’s presence, but even more so due to the presence of Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn’s first wife, Natalya Reshetovskaya. She had asked Roy whom she might trust to take her typescript/manuscript about her life with Solzhenitsyn to the West for safekeeping. Steve had experience with taking out—and bringing in—books, from Russia to the West and vice versa, and he agreed to do so. (It may have been one reason why neither Steve nor I could get a visa to travel to Russia from 1982 to March 1985. On March 11, 1985, Mikhail Gorbachev came into office.)

Boris became a friend, introducing me to the Rabkor team, the Fellows at his Institute, sharing insights, history, and gossip about the media and political scene. He visited The Nation many times over the years and contributed articles. Boris is a person of integrity, great intelligence, and, yes, irony, humor, and creativity, qualities necessary to keep living and working in Putin’s Russia.

Boris has been a steadfast and productive dissident. He was editor of the samizdat journal Left Turn from 1978 to 1982, which led to his arrest for “anti-Soviet activities” in 1982. He was released in 1983. In 1988 he became coordinator of the Moscow People’s Front, and in 1990, he was elected to the Moscow City Soviet. He cofounded the Party of Labor. In 1993, he was arrested for his opposition to President Yeltsin during the September-October constitutional crisis—but was released quickly after international protests. Later that year, his job and the Moscow City Council were abolished under Yeltsin’s new Constitution.

Boris wrote in a letter to global supporters when he was arrested last year:

This is not the first time in my life. I was locked up under Brezhnev, beaten and threatened with death under Yeltsin. And now it’s the second arrest under Putin. Those in power change, but the tradition of putting political opponents behind bars, alas, remains. But the willingness of many people to make sacrifices for their beliefs, for freedom, and social rights remain unchanged.

I think that the current arrest can be considered a recognition of the political significance of my statements. Of course, I would have preferred to be recognized in a somewhat different form, but all in good time. In the 40-odd years since my first arrest, I have learned to be patient and to realize how fickle political fortune in Russia is….

The experience of the past years…does not dispose much to optimism. But historical experience as a whole is much richer and gives much more grounds for positive expectations. Remember what Shakespeare wrote in Macbeth?

“The night is long that never finds the day.”

Boris’s daughter, responding to Navalny’s death, made this statement: “And for all of us, this is a special sign, especially for those of us who have relatives, friends, associates, in the hands of Putin’s regime, we are all not safe. Now when Boris is behind bars, it is especially important…to show even more solidarity around Boris, around his case and around other political prisoners.”

Last week, in a post on Telegram, Boris said he was “in a great mood as always” and that he plans to continue collecting materials for new books, “including descriptions of prison life.”

Last year, galvanized by Boris’s detention, a “Free Boris” movement arose globally and, perhaps more importantly, across Russian cities and towns. Spontaneous demonstrations were held; online protests and coordinated international actions commemorated Boris’s birthday in August. Thousands of signatures were collected from prominent intellectuals, activists, and political figures. Brazilian President Lula da Silva criticized Boris’s detention, as did leaders in other BRICs countries whom Putin counts as allies.

Significantly, when Boris’s first arrest occurred last year two pro-Kremlin figures, RT’s Margarita Simonian and analyst Sergei Markov, were quoted in The Washington Post stating what a mistake it was.

When Boris was released on December 13, 2023, it was a demonstration that international pressure and solidarity works.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →According to the Moscow court’s decision, Boris will be sent to pretrial detention center No. 12 of the Federal Penitentiary Service of Russia in Moscow. In Moscow, this center is known as one of Russia’s harshest lockups—word is that he is being held in a cell with 15 other men.

For information on how to show solidarity and support, use Patreon or Busti. Visit freeboris.info.