My Search for Barbie’s Aryan Predecessor

The original doll was not made by Mattel but by a business that perfected its practice making plaster casts of Hitler.

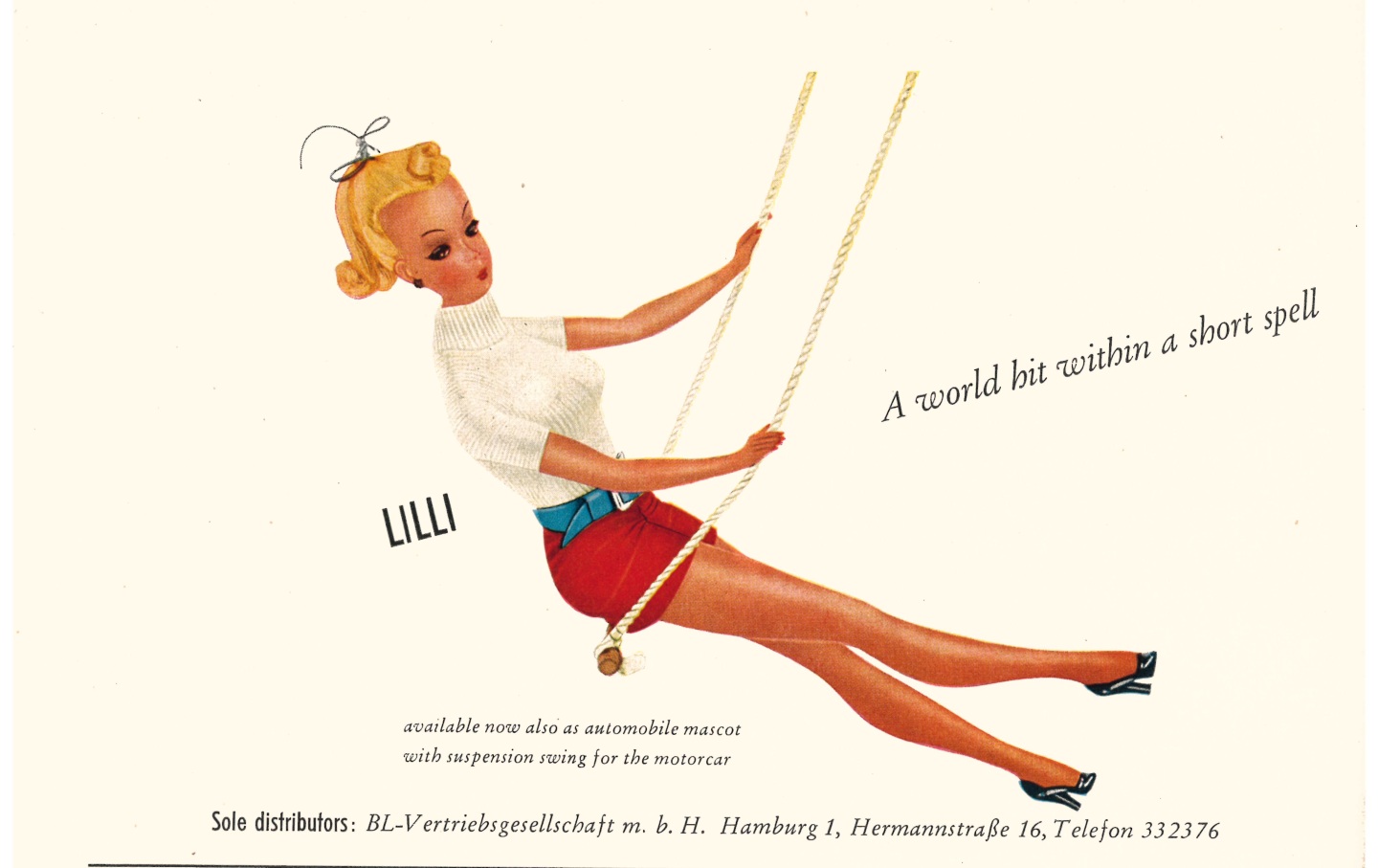

Images of Lilli from the February 1956 cover of Spielzeug Export.

(Nuremberg Toy Museum)Almost exactly 64 years after Barbie’s first Toy Fair, I flew to Berlin. It was March 4, 2023. I was staying in the second bedroom of an old fourth-floor walkup with a former DJ in her 30s, who now ran a seasonal arepa stand. The apartment was sandwiched between a street named for Karl Marx and one whose namesake discovered an inflammatory disorder that can cause rectal bleeding.

I had just read a trend report predicting that the year would be marked by what it called “franchise fatigue,” the collective exhaustion brought on by the “constant and inevitable churn” of spin-offs and reboots. The movies and TV shows of the past decade had been dominated by sequels, remakes, and familiar storylines repackaged from video games, bestsellers, and tweets. One site had declared 2022 “The Year of the Reboot,” and the new year showed no signs of slowing down. Just three of 2023’s 40 “most anticipated” film releases, per one list, would be based on new material; the others broke down into “17 sequels, eight reboots and remakes, and four spin-offs.” If anything, the adaptations seemed to be getting more brazen. That spring alone was slated to bring three movies about inanimate objects (the BlackBerry, Air Jordans, Cheetos), and two about games (D&D, Tetris). Fatigue seemed inevitable. It was “entertainment’s law of diminishing returns,” the trend report observed; the sequel was always worse.

And yet, in the midst of all this, Hollywood was reviving another familiar media property: Former indie darling Greta Gerwig was directing a Barbie movie—one that I would eventually review for this magazine. The film wouldn’t come out for several months, but it had already bucked any trend toward fatigue. The trailer alone had started a craze. It depicted Barbie as not merely an icon but as an origin story—an alien construction whose descent to Earth, like the monolith in 2001: A Space Odyssey, catalyzed a new era in human civilization. In Stanley Kubrick’s version, the monkeys who stumble upon the monolith learn to use weapons, thus bringing about, per the title card, the “dawn of man.” The trailer’s nearly shot-for-shot re-creation of that scene posited Barbie instead as the genesis of modern girlhood. “Since the first little girl ever existed, there have been dolls,” the voiceover explained. “But the dolls were always and forever baby dolls, until…”—until, that is, Barbie. If the tone was tongue-in-cheek, the assessment was blunt: Barbie, the first adult doll, had molded American girldom, a modern Prometheus making children from clay.

Barbie had, of course, made an indelible imprint on American girlhood; she embodied stereotypical Western beauty standards. But the doll’s mythos as some radical departure from a market of baby-dolls mystified me, in part because she was not—as the movie trailer claimed and as Mattel has maintained—the first adult doll brought into toy stores. She was not an original invention, or even the original Barbie really, but a knockoff, copied from another doll, in another country—and not subtly either. This original had not been some relatively unknown quantity, rebranded before anyone got a clue. She had been distributed all over Europe, sold not just to children and women but also grown adult men. She’d had a department store aisle of accessories; she had been made in marzipan; she had been photographed with Errol Flynn. This doll too had been made into a movie, a film to which an entire nation paid attention, whose promotional campaign had wormed its way into everyday consciousness.

Perhaps most curious of all was the fact that this proto-Barbie had not originated with some small craftsman or mom-and-pop shop but from the operations of the most powerful newsman on the continent, an executive whose control over the information ecosystem of postwar Europe drew more comparisons to monarchs than publishers: “No other man in Germany, before Hitler or since Hitler, has accumulated so much power,” one of his rivals said, “with the exception of Bismarck and the two kaisers.” His middle name was Caesar, and he acted like it. He often answered the phone, sans irony: “This is the king himself speaking.”

But the king’s doll had mostly been forgotten. Barbie had somehow beaten out one of the most famous dolls in the global toy capital and kept it hidden for decades, disappearing her predecessor into a marketing parable about Mattel’s supposedly novel adult doll. That’s why I had traveled to Berlin—to track down this doll that Barbie’s founders had, for decades, done their best to suppress.

Iwas commuting each day to the headquarters of Axel Springer, a media empire which some might know as the owner of Politico. The founder, also named Axel Springer, had built his headquarters just 12 meters from the border between East and West Germany—a portent of their eventual reunification, but also of his publishing ambitions. He wanted a national monopoly. After the Second World War, with little competition remaining, Springer assembled a stable of German papers, covering news morning, evening, night, on every topic, but especially those dearest to him. As he saw it, the liberal papers of earlier years had failed to stop fascism, and then the war had wiped them out, along with most of bourgeois life. The stage was set for a new kind of journalism, a lighter mode of addressing the public: emotional, spiritual, conservative, if not yet openly so.

Springer had always been careful about exposing himself to allegations of agenda-pushing. During the war, he had not been a Nazi, albeit on a technicality, having secured a medical exemption from military duty. Instead, in 1934, Springer joined the National Socialist Motor Corps—ostensibly, he said later, to make him “a Nazi-uniformed buffer for the family.” The Motor Corps, he alleged, “made no great ideological claim,” but merely “combined politics with the motor sport that I loved so much”—though one prerequisite for admission was an “inner willingness to fight,” and the group had been founded to actualize Hitler’s belief that mobile operations were essential for disseminating “National Socialist ideology and election propaganda.”

After the war, Springer’s attitude toward national affairs was unambiguously right-wing; the pro-austerity capitalist and German nationalist would become, as Tablet put it, “the closest thing the Germans had to a Rupert Murdoch.” But in print, he masked overt politics behind an unrelenting cheeriness—blending human interest, celebrity gossip, animal-centric stories (“Cat Adopts Blind Dog”), and the horoscopes that Springer himself, who had a private astrologer on his payroll, followed obsessively. “It was clear to me since the end of the war that one thing the German reader didn’t want was to think deeply,” Springer told an interviewer. “And that’s what I set up my newspapers for.”

I’d come to look at the archives of maybe his most influential outlet, a daily paper called Bild Zeitung. Founded seven years pre-Barbie, in 1952, Bild was a knockoff in its own way—a German version of an English tabloid Springer had seen on a trip, called, aptly, the Daily Mirror. Picture-heavy, offering shorter stories and bolder headlines, the Mirror’s coverage was sensational and as sexy as its comic, “Jane”—a pinup whose wardrobe malfunctions seemed to take the term “comic strip” literally. Originally titled Jane’s Journal—Or the Diary of a Bright Young Thing, the cartoon followed a “curvaceous blonde secret agent,” who “tangled with Nazi spies, tumbled down cliffs and became caught in tree branches in episodes that invariably concluded with her stripped down to her underclothes.”

The Mirror struck Springer “as the printed answer to the electronic age,” a visual medium primed to contend with a burgeoning competitor called television. In 1952, Springer set out to replicate its success with a German equivalent of the Daily Mail or our own New York Post. Bild was an instant hit, attracting 4 millions subscribers within its first decade. When politics appeared in its pages, it was synonymous with the publisher’s brand of postwar conservatism. Springer’s foremost enemy was Communism, which he saw as the obstacle to both a united Germany and a united news market. (There were rumors, rejected by Springer though later reported by Nation contributor Murray Waas, that the mogul had gotten $7 million from the CIA.)

“When we hit five million subscribers,” Springer once wrote to a friend, “then we will order the people to walk on their hands and they will do it.”

But over the summer of 1952, the tabloid Springer would call his “dog on a chain” was barely a puppy. On June 24, as Springer prepped the first issue for print, he noticed the four-page broadsheet had a blank on page two. Amid the pasting of pictures and inverted pyramids, Springer had ignored a narrow chasm, too small for a photo, too large to leave empty. A comic could fit, or some simple drawing. Springer summoned a friend, a hulking blond giant named Reinhard Beuthien who was an illustrator at another Springer paper, and as cartoonishly macho as Barbie would be feminine—more G.I. Joe than Ken.

The paper was already printing when an editor ran to Beuthien’s office, shoved a copy under his nose, and pointed to the void: “I need something immediately to fill in this blank.” Beuthien sketched a pretty cherub with plump cheeks. But the editor wanted a more mature silhouette that would keep readers coming back. “In the greatest silence, I erased the plump cheeks and drew a thinner face,” Beuthien recalled. “I drew the face even thinner, and the colleague continued to rage.” Beuthien swapped its newborn frame for a starlet’s body, its Winston Churchill scalp for a blonde ponytail, its nappy for a pencil skirt. The editor snatched the sketch and ran. The next morning the paper debuted on newsstands with a comic one critic called the “ultimate woman-child fantasy.” Her name was Lilli.

This new character seemed as much an imitation as the paper itself, an answer to the Daily Mirror’s Jane. Like Jane, Lilli was an archetypal blonde with an affinity for flouting dress codes and pursuing rich men. Men apparently liked her back: The comic attracted a following nearly overnight, becoming the rare drawn character in Germany to get her own fan mail. “Readers look for ‘What Lilli said today,’” Beuthien told a friend, “then throw away the newspaper.” Lilli would become the avatar of the largest media conglomerate on the continent, the Mickey Mouse of postwar Germany. Like today’s mascots, she was omnipresent on merchandise—from postcards to champagne bottles to novelty perfume. Life-sized Lilli cutouts adorned street kiosks, guiding readers toward the paper like a cardboard Vanna White. Around Bild’s third birthday, Lilli gained a dimension and became a doll.

Beuthien obsessed over Lilli’s plastic reproduction. The model had to conjure the Lilli of the comic—pretty, but insolent; sultry, but cherubic; sufficiently chaste to Bild’s most conservative readers, but imbued with insinuation and “double meaning.” He needed a perfect replica, a doll that could imply all that without a caption.

A prolonged search led him to the offices of O.M. Hausser, a brother-owned business once famous for toy soldiers, but which had spent the war years making Nazi figurines and plaster casts of Adolph Hitler. After the war, and their own de-Nazification trials, Rolf and Kurt Hausser began experimenting with dolls. It was their sculptor who designed the Lilli that debuted in August of 1955: impossibly thin, synthetically perky, eyebrows angled over a sidelong gaze, already bored by her beholder. Like the Barbie she would inspire, Lilli’s painted-on stilettos were too pointed to provide support; Lilli’s feet had holes so she could be nailed to a stand. Rolf Hausser’s mother-in-law, Martha Maar, made her clothes, designing a wardrobe of a hundred-odd costumes ranging from flight attendant to nurse to something called, simply, the “Hungarian.” Each doll carried a tiny copy of Bild—miniature papers featuring miniature articles about Lilli, each seeming to heed Beuthien’s insistence on “double meaning,” which is to say they were subtly horny. “‘I’ve been waiting for you for a long time,’ says Lilli,” read one headline. “Today, since you have me,” another read, “you will never be alone.”

The doll’s implicit audience was not children but adults. She was too expensive, initially, for most kids. Lilli was sold at newsstands and tobacco shops, an advertising gimmick that became a raunchy gift for girlfriends or bachelor parties. A car ornament model proved especially popular with men. “She was an irresistible gag,” one buyer told the eccentric Andy Warhol muse and Barbie collector BillyBoy* (he spells his name with an asterisk). “Imagine, a doll with big tits and long legs! Nothing like her existed before, and she was such a clever joke. We’d have such laughs over this gadget, especially on Saturday nights when we’d all drive around cruising for girls and having beers at local pubs.”

But Lilli was not, as many have claimed, an “escort” or “call girl” or, per one outlet, “a fictional prostitute” who would “do anything with sweaty clients, provided the money was right.” She was not even a “sex doll,” at least not in the modern sense. She was an adult doll, and sex was always her subtext. “The prudery of the Nazi era was still rife in Germany in those years,” Bild editor Hans Bluhm recalled. She was about as pornographic as Betty Boop. “Lilli was a sex ingredient of a saucy but harmless kind.” Rolf Hausser agreed. “This is most important: No one could say she wasn’t a virgin.” The doll was “not intended for men more than for women,” he insisted. Eventually, she became ubiquitous enough that children became her customers too, as Lilli moved to airport lobbies, then toy stores. “Product for all,” one ad read, “from child to grandpa.”

Above all things, Lilli was a marketing strategy, an extension of the Springer brand and its most effective ad. When the company hired models to dress as the doll for a cross-country press tour, Germans lined up for autographs and the occasional kiss. Lilli was more than Bild’s public face, she was a symbol of the consumer society the publisher had endeavored to bring about. (As Springer ramped up his support for reunification, an internal memo noted that a commercial about Lilli would be used for “propagandistic activity” across West Germany.)

Lilli’s fame reached its apex in 1958, when Bild, much like Mattel would many years later, produced a feature-length film. The director didn’t want a well-known face to play Lilli; he wanted an everywoman—so long as she was blonde, thin, and under 25. Springer announced a national contest to find its star. The winner, a 21-year-old Dane named Ann Smyrner who’d been spotted in a grocery store, made international news. German outlets fumed over the foreign selection; American ones simply gawked at the new blonde. Her headshot ran everywhere from the Fort Worth Star-Telegram to the Daily Oklahoman, to the Reporter Dispatch in White Plains. (In the film, Smyrner plays a newspaper reporter, who hunts down stories with a mix of combat skills and sexual prowess. By the end, she has gotten mixed up in an international syndicate of highly skilled counterfeiters.)

When I showed up at the Axel Springer archive in Berlin, I had thought, maybe foolishly, that the company would have the complete Lilli archive, or at least a decent chunk of it. The company kept a records library, which collected everything from advertising materials to building construction history to documents “from all departments and units” of Axel Springer dating back to its founding. The library had a robust online presence, including an illustrated history of the doll. But when I reached the firm’s archives, where I was to spend the next few days, I realized my mistake.

The archivist’s name was Lars Broder-Keil, a man in his 40s with glasses, gray hair, and the careful demeanor of someone who reminds a lot of visitors to please put on gloves before touching anything. He had laid out on a small table everything he could find on Lilli: a few Springer biographies, one history on German publishing, and a couple original Lilli dolls in their signature plastic tube. He’d dug out old issues of Bild—oversize broadsheets bound together by year, in equally oversize books. There was one self-published Lilli history, one teddy bear from the German toy maker Steiff (who had produced Lilli’s pet poodle), and one thick binder of seemingly every e-mail the archive had gotten that mentioned the doll’s name. But little of it came from the 1950s. There were no memos from Springer about design specs or breakdowns about rollout. There were no Bild Lilli sales stats or fan letters or staff notes. Of course, it’s possible that Axel Springer had simply elected not to share its internal records. As a private company, Axel Springer wasn’t obliged to disclose trade secrets to the press. But Lars himself seemed confused about the other missing files; the archivists had spent years looking for Lilli material, he told me. His predecessor had taken out newspaper ads and posted on forums, looking for any surviving accounts of how exactly she came to be. (Most of the e-mails he had, in fact, were just replies to those posts.)

Lars suggested I look through municipal archives to see if I could turn up the Haussers’ corporate records. I did, along with basically every state archive, library, or Barbie collector I could find in northern Bavaria and several more outside it. Eventually, I found some records in the city archives of Ludwigsburg, a small town near Stuttgart where the Haussers had first started the firm. The archivist did have birth, death, and marriage records for its founders, as well as the Haussers’ custom stationery. But there too, the search for Lilli came up empty. “Unfortunately,” the city archivist wrote to me, “we do not have any detailed documents on the Hausser toy factory.”

Nor did Rolf Hausser’s living daughter, a veterinarian and accomplished violinist, whom I texted on WhatsApp. Or German doll collector Silke Knaak, who wrote the first book about Lilli. Or Peggy Gerling, a Barbie collector who investigated Lilli for trade magazines in the ’90s. The Haussers appeared to have thrown their papers out, or somehow let them vanish. “I absolutely didn’t want to believe that Lilli’s documents had disappeared,” Italian economist Marina Nicoli, who herself went on a Lilli deep dive earlier that year, told me. But she’d heard as much from Dieter Warnecke, a German Barbie historian who’d corresponded with Rolf Hausser for years. He “kept insisting that I needed to accept reality.” Lilli, apparently, remained something of a blank.

But that seemed somewhat intentional. Mattel’s founder Ruth Handler, who would rebrand Springer’s doll as her own, had spent years obscuring Barbie’s backstory, avoiding any mention of Bild’s Lilli and sending legal threats to those who happened to bring her up. Mattel had sued collectors and magazines and self-published authors and smothered more with cease-and-desists. The campaign stretched well past the fifties, into the 21st century. But it had started years earlier, with the Haussers, with a conniving toy mogul named Louis Marx, and above all, with Ruth.

Support independent journalism that does not fall in line

Even before February 28, the reasons for Donald Trump’s imploding approval rating were abundantly clear: untrammeled corruption and personal enrichment to the tune of billions of dollars during an affordability crisis, a foreign policy guided only by his own derelict sense of morality, and the deployment of a murderous campaign of occupation, detention, and deportation on American streets.

Now an undeclared, unauthorized, unpopular, and unconstitutional war of aggression against Iran has spread like wildfire through the region and into Europe. A new “forever war”—with an ever-increasing likelihood of American troops on the ground—may very well be upon us.

As we’ve seen over and over, this administration uses lies, misdirection, and attempts to flood the zone to justify its abuses of power at home and abroad. Just as Trump, Marco Rubio, and Pete Hegseth offer erratic and contradictory rationales for the attacks on Iran, the administration is also spreading the lie that the upcoming midterm elections are under threat from noncitizens on voter rolls. When these lies go unchecked, they become the basis for further authoritarian encroachment and war.

In these dark times, independent journalism is uniquely able to uncover the falsehoods that threaten our republic—and civilians around the world—and shine a bright light on the truth.

The Nation’s experienced team of writers, editors, and fact-checkers understands the scale of what we’re up against and the urgency with which we have to act. That’s why we’re publishing critical reporting and analysis of the war on Iran, ICE violence at home, new forms of voter suppression emerging in the courts, and much more.

But this journalism is possible only with your support.

This March, The Nation needs to raise $50,000 to ensure that we have the resources for reporting and analysis that sets the record straight and empowers people of conscience to organize. Will you donate today?

More from The Nation

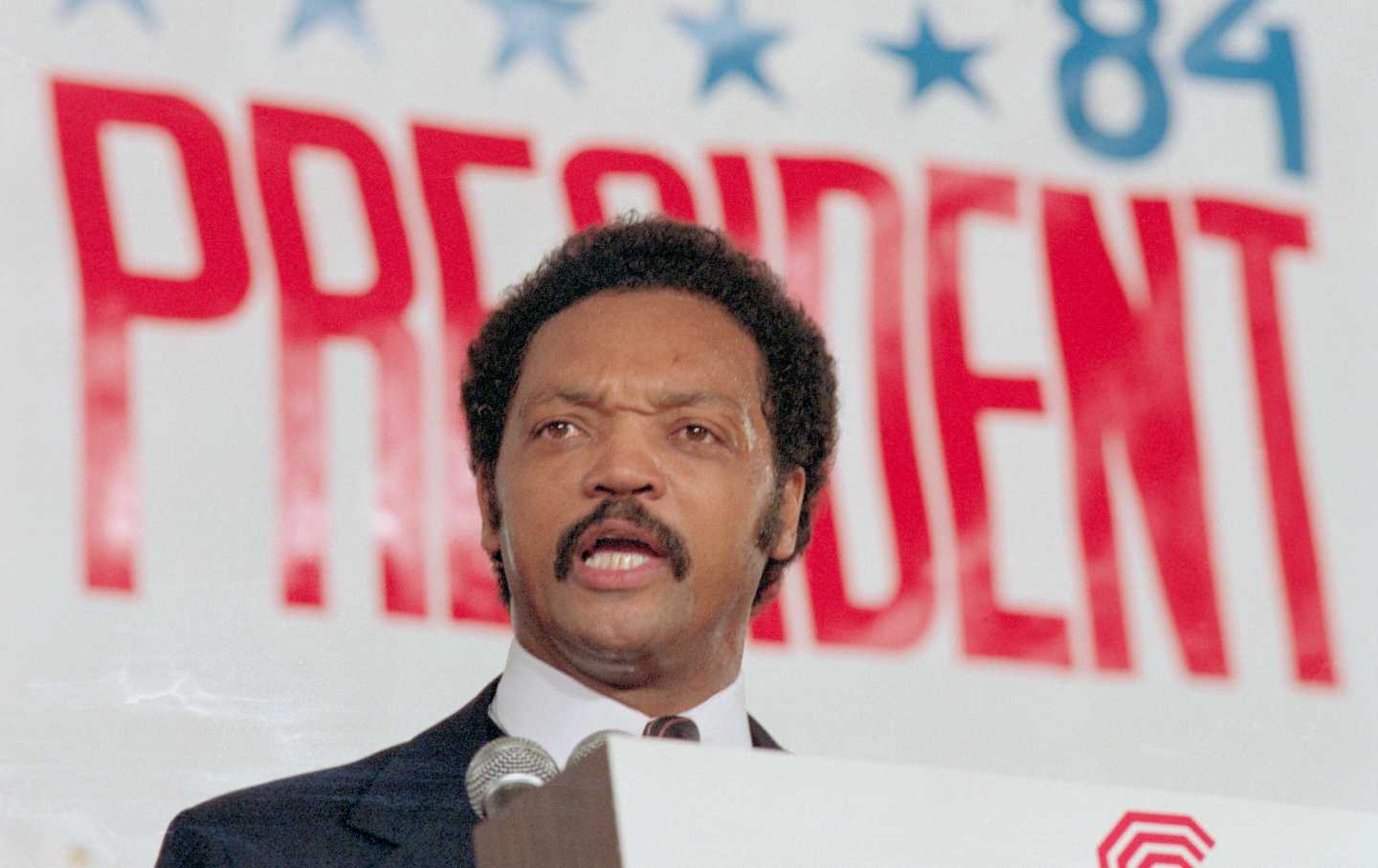

In Memoriam: the Rev. Jesse Jackson (1941–2026) In Memoriam: the Rev. Jesse Jackson (1941–2026)

The civil-rights activist and founder of the Rainbow PUSH Coalition changed what’s possible in politics.

The Real Reason Americans Love Guns The Real Reason Americans Love Guns

With a weak social safety net, a gun offers a false sense of personal power and security.

The Endless Hypocrisy of Bari Weiss The Endless Hypocrisy of Bari Weiss

She claims to be a free speech champion. But as her actions at CBS News keep showing, she seems to think free speech should run only in a rightward direction.

What Will Be Left After the University of Texas Destroys Itself? What Will Be Left After the University of Texas Destroys Itself?

UT-Austin has collapsed its race, ethnic, and gender studies into a single program while a new policy asks faculty to avoid “controversial” topics. But the attacks won’t end there...

The Corporate Media Is Head Over Heels for the Iran War The Corporate Media Is Head Over Heels for the Iran War

Donald Trump’s attack may be surreal, unjustified, and illegal. But that’s not stopping the press from turning the propaganda dial way up.

The Disturbing History of ICE’s “Death Cards” The Disturbing History of ICE’s “Death Cards”

The Vietnam-era practice is yet another example of ICE agents thrilling to the brutality they have been encouraged to cultivate.