Inside the Fight to Bring Midwives Back to Massachusetts

Midwifery is often a cheaper and safer alternative for some childbirths, yet the state’s policies require midwives to jump through increasingly difficult hoops to practice.

A student midwife taking a mother’s blood pressure.

(Jessica Rinaldi / Getty)

Emily Anesta ended her maternity leave in an unconventional way—testifying at the Massachusetts State House. With a panel of legislators stretched above her and a newborn in her lap, Anesta recounted the story of her home birth. This was her (and her baby’s) first time in the halls of the State House. Anesta was trained as an engineer, a far cry from the world of amendments and articles. But, for Anesta, the cause was worth the whiplash: she was campaigning for professional midwife licensure, a measure that would legitimize the work of midwives who do not work in hospitals.

“I knew… you know, that it was possible,” she says, “to come out of the experience of pregnancy and childbirth feeling strong and healthy and supported and powerful—that’s how I felt. And I knew that that was possible for many more people.”

Often called the “medical mecca” of America, Massachusetts boasts some of the best healthcare in the world. Despite this distinction, or perhaps because of it, alternative methods tend to get seriously slighted. Midwifery, a healthcare model which emphasizes low-intervention and individualized reproductive care, for example, is a cheaper and safer alternative for some childbirths. Yet, with Massachusetts’ over-medicalized and restrictive policies, midwives have to jump through increasingly difficult hoops to practice.

For the past century, lawmakers have blocked policies concerning birth center regulations, midwife licenses, and paying for midwife-led births through MassHealth. This has led many expecting parents to have no option but to give birth in a hospital. Tired of operating in the margins of the healthcare system, Massachusetts midwives have been fighting tirelessly for birth equity.

Her testimony and statehouse visit were Anesta’s self-proclaimed “baby steps” into birth equity advocacy. Three years after that experience, she cofounded the Bay State Birth Coalition, a consumer advocacy group that promotes midwifery and non-hospital birth options within Massachusetts. “The midwifery model of care is special,” she says. “[Midwifery] is a model that really centers the individual’s rights and bodily autonomy.”

Being a Bay State birth equity advocate is an uphill climb—Massachusetts has long been the center of the anti-midwifery movement. One hundred years before the movement became mainstream, Massachusetts physicians wanted to confine obstetric care to male doctors, arguing that women were unfit for the profession. In 1820, Boston physician John Ware wrote that “there is, perhaps, no place of equal size, in which [midwifery] has been so entirely confined to male practitioners, as [Boston].” By the early 20th century, Massachusetts had become one of the few states in America to explicitly criminalize midwifery, prosecuting midwives for attending home births.

The campaign to eliminate midwifery arose from a series of “interprofessional battles,” says Eugene Declercq, Professor of Community Health Sciences at Boston University. “As obstetrics rises as a profession, it becomes more and more difficult to sustain the level of respect [physicians] want to have if—quote unquote—“these women” can keep [practicing] it.”

Between 2011 and 2020, rates of severe maternal morbidity— instances where unexpected complications in labor and delivery significantly impact the birthing person’s health—doubled in the state of Massachusetts. Though Massachusetts is home to the best hospitals in the country, care is massively stratified across geographic, racial, and ethnic lines. The report, which the Department of Public Health released in July 2023, showed that rates of severe maternal morbidity for Black mothers are almost two and a half times higher than for their white counterparts, and almost one and a half times higher for Hispanic and Asian mothers.

In a healthcare system imbued with institutional racism and bias, white women have a better chance of being listened to, said Tiffany Vassell, a labor and delivery nurse and midwifery advocate. Black women are three times more likely to die from a pregnancy-related cause than their white counterparts and more likely to experience mistreatment during childbirth. At the same time, many studies have shown that midwife and non-hospital birth care is associated with fewer reports of discrimination amongst Black and brown birthing people.

During the birth of her first child, Vassell’s doctors kept checking her, giving her cervical exams—which she now reflects on as being unnecessary. Eventually, they recommended that she get a C-section, a surgical delivery of the baby. But Vassell was adamant about having a vaginal birth. “I had to be very aggressive and very clear about not wanting a C-section,” she said. Vassell’s story is not uncommon. Black women are pressured twice as often as white women to get C-sections, despite the fact that they have a lower chance of surviving them.

“That kind of started the fire within my gut with wanting to advocate for folks and their birthing experience,” she says. Now, she is a community advocate at the Neighborhood Birth Center, where she teaches workshops about birth centers and the midwifery model of care. The Neighborhood Birth Center has created new policies supporting midwives and has been attempting to establish a birth center with fair wages and reasonable work hours for midwives, relying on community support and legislative change to provide non-hospital options for residents in Eastern Massachusetts.

Many people of color in Massachusetts are unaware that there are non-hospital options available, Vassell explains. By introducing them to the midwife model, which prioritizes relationships and continuity of care, she hopes to improve health outcomes for her community. “I want to empower folks. I want folks to feel like when they go into a room with a clinician, that they feel heard and seen, and that they get the care that they know they deserve.”

Promoting the midwifery model of care has been historically difficult. Massachusetts is one of 14 states that do not provide licensure for professional midwives. Their practices are not explicitly illegal, but they are not regulated by the state either. The only midwives that operate in Massachusetts are nurse midwives, who have had extensive hospital training.

Rachel Blessington, the founder of the Worcester Community Midwifery, began as a labor and delivery nurse in a community hospital but found the work discouraging. “A hospital is trying to serve so many patients in a day, it feels like turning over a restaurant table,” she says. “That leads to a depersonalization of care.”

She went back to school to become a professional midwife, but professionalizing the field is enormously difficult. Professional midwives can’t bill most insurance companies, which means mothers who opt for a home birth can receive a bill that ranges from $3,000 to $9,000. Nor can professional midwives operate independently in birth centers—freestanding healthcare facilities that promote midwifery and low-intervention births, reduce racial disparities in pregnancy and lead to a decrease in surgical interventions during childbirth.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →The Worcester Community Midwifery isn’t a birth center, but Blessington wants it to be. Freestanding birth centers provide a third option, apart from hospitals and home births, for people to give birth. They look more like houses, instead of hospitals, replacing the thin sheets of a hospital bed for full-size beds with comforters and large tubs. Giving birth at a birth center, Blessington says, “is a lot like a home birth at someone else’s place or a beautiful inn.” At a birth center, midwives are able to get to know their patients and spend more time with them. “The care outcomes are so much better because the style is more supportive.”

There are 400 accredited birth centers in the United States, but only one in Massachusetts—the Seven Sisters Midwifery in Northampton. The scarcity of centers had dire consequences on the growth of midwifery in the state. Most professional midwives can only get their training at an accredited birth center. “Without more birth centers, we don’t have places to train more midwives, especially ones that reflect our community,” Blessington says.

Ginny Miller, the current director of the Seven Sisters Midwifery tried to start a midwifery 40 years ago. “But my license did not allow me to work independently. I needed a supervising physician, and I couldn’t find anyone who would take that role on,” she says, referencing a regulation that required an ob-gyn to observe nurse-midwives. Once that law was overturned in 2012, it took eight years for Seven Sisters to build an entirely new building in compliance with antiquated and overly complex state regulations for birthing centers.

Though birth centers aim to demedicalize the birthing process, Massachusetts regulations make it impossible for a birth center to open without certain specifications—a birth center must have lighting, ventilation, and equipment fit for a surgical suite. Additionally, despite the 2012 law, every freestanding birth center must have a supervising obstetrician or gynecologist who oversees the facility. Though useful in a hospital, these regulations are unnecessary for the midwife’s scope of practice—low-intervention, low-risk births.

Opening a birth center may be hard, but keeping it open is even harder. Midwives get reimbursed 85 percent of what insurance companies pay doctors for the same care. This leads to a difficult financial deficit, though midwife-facilitated births are cheaper than hospital births. “If we don’t get either a change in reimbursement or some of the grants, we have about maybe four to five more months of payroll, we have to close,” Miller says.

This isn’t to say that there isn’t demand for non-hospital options. Seven Sisters hasn’t spent a single cent on advertising, according to Miller. “We can’t spend money on marketing, because we turn away too many people,” she says. The midwifery has a waiting list of three to five families a month.

After a sustained push by midwives and consumer advocates across the state, legislators began paying attention. This is the first time a bill that upheld professional midwife licensure has passed the Massachusetts House. The House also accepted key amendments, such as redefining what is considered a “low-risk” birth and providing equitable reimbursement for midwives—two major obstacles to non-hospital birth care in Massachusetts.

Different variations of the bill have been in the House for 40 years, blocked by medical doctors and their advocates trying to keep pregnancy and childbirth in the hospital. Getting the bill on the legislative agenda required a coordinated and careful effort—the advocates knocked on doors, implored legislators, conducted research, and pushed to get the bill on the desks of people that mattered. In late 2023, the Bay State Birth Coalition led a rally in front of the State House. Standing on a ledge in front of the towering black gates, activists spoke about the importance of midwives. Children held up signs proudly proclaiming: “A midwife caught me!”

Six months later on June 20, 2024, the same cheerful yet forceful sentiment—midwives save lives—went from outside of the gates to inside the House chamber. In an emotional House session, representatives shared their birth stories. “Midwifery was the norm for the segregated Black community,” Representative Brandy Fluker-Oakley said in her speech. She recounts the story of her own mother being born through a midwife-assisted vaginal birth, and the importance of midwives to her family. Representative Christopher Worrell told the House of his wife’s pregnancy loss. “[My wife’s] strength is a gift, but should not be required for any pregnant person,” he says. “Inaction on this blatant disregard for Black women’s health affects mothers and our babies.”

As the electronic ticker on the wall counted the votes, it soon became clear that not only would the maternal health bill pass, it would pass overwhelmingly. Though they needed to be quiet in the chambers, once outside of the room, excitement and tears resounded as the women hugged each other, relieved that their efforts had culminated in momentous change. Though there is still much work to be done (namely, passing the bill through the state Senate and the governor’s office), they could stop holding their breath. “We can’t even express our joy enough, because it has just truly been so much work to finally see that folks believe that birthing people deserve this kind of care,” Vassell says. “It has been just a labor of love.”

More from The Nation

Deportation and the Silence That Follows Deportation and the Silence That Follows

When ICE abducted my father without cause, something strange filled his vacancy.

On Cora Weiss (1934-2025) and Peace On Cora Weiss (1934-2025) and Peace

Cora Weiss died in December at age 91. She never stopped campaigning to save the world from nuclear destruction.

The Media’s Coverage of the Venezuelan Coup Has Been Dreadful The Media’s Coverage of the Venezuelan Coup Has Been Dreadful

War may be the health of state, but it’s death to honest journalism.

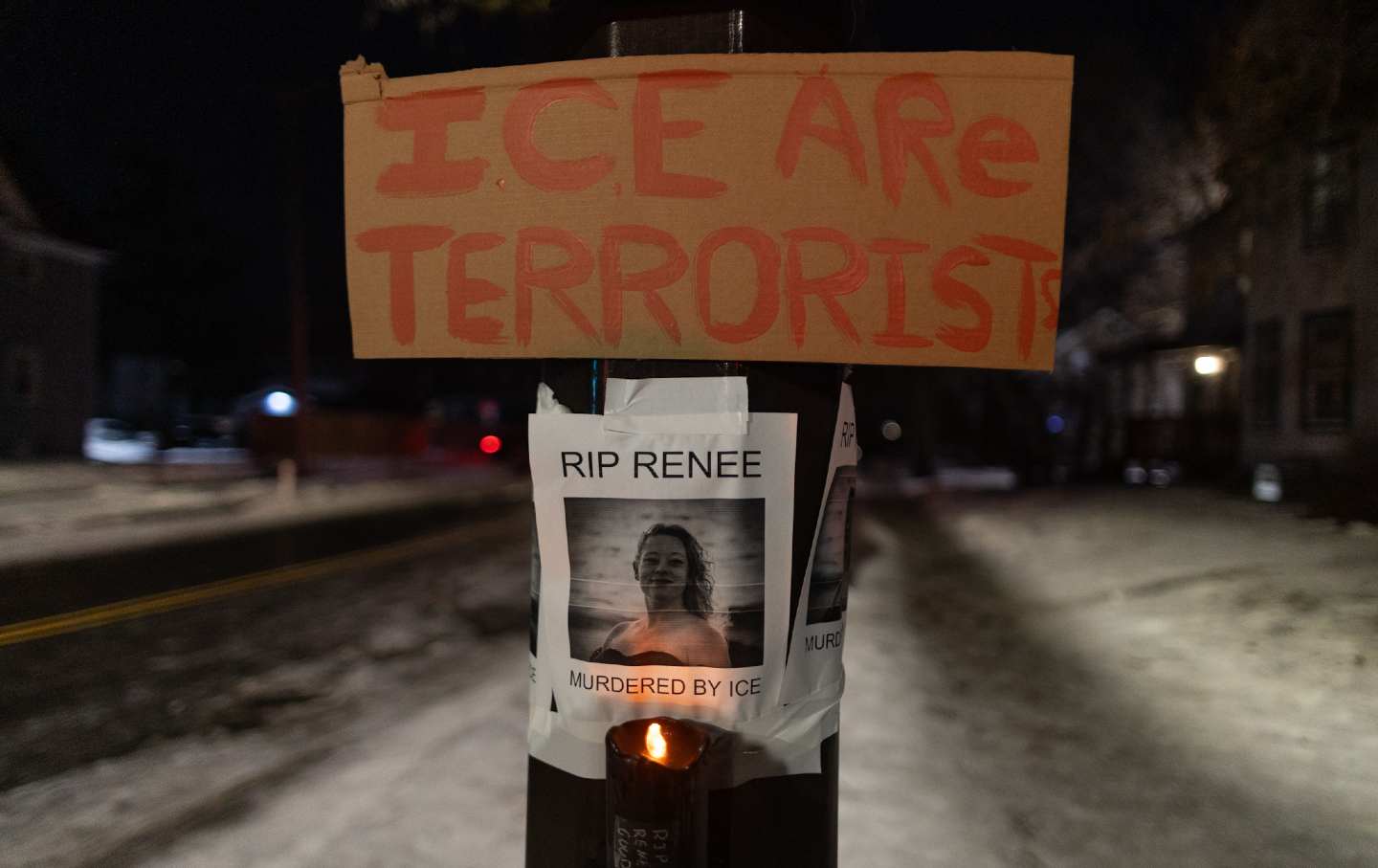

Dismantling the Meme Logic Behind Renee Good’s ICE Execution Dismantling the Meme Logic Behind Renee Good’s ICE Execution

The Trump administration is once more invoking upside-down alibis of state to conjure the bogus specter of imminent threat.

Minneapolis to ICE: Get the Fuck Out! Minneapolis to ICE: Get the Fuck Out!

An ICE agent shot dead Renee Nicole Good. Residents are ready to fight back.

Prosecute Renee Nicole Good’s Murderer Prosecute Renee Nicole Good’s Murderer

The ICE agent who killed Renee Nicole Good not only can be held accountable for murder—he must be.