How Black People Won the Battle of Montgomery

The lesson of the events at the Montgomery Riverwalk is that when Black people see something, we do something

White privilege met Black pride down by the Alabama River, and on this particular occasion, white privilege got its ass whupped. As seen all over social media, a melée broke out on the riverwalk in Montgomery over the weekend, after a group of white men and women attacked the Black first mate of a popular riverboat; he had been asking them to move their pontoon boat so the riverboat could dock. At least four of six white boaters delivered a number of punches to the first mate, before a more numerous group of Black people came to the his defense.

I’m not sure if it’s appropriate to call what was essentially a mini race riot “joyful,” but I took a lot of joy from watching the fracas. To understand why, you have to be at least more knowledgeable about the history of white violence against Black people in this country than a person currently being educated in Florida. The white people who attack us in broad daylight always think they’ll get away with it. Usually, they’re right. This time, however, they were wrong. And privileged white racists learning they are wrong in real time is a joy to behold.

Context matters, and the context for this fight starts some 45 minutes before any video starts rolling. The Harriet II Riverboat gives cruises up the Alabama River. At around 7 pm on Saturday, August 5, it was attempting to dock at its reserved spot on the Montgomery Riverwalk. A private pontoon boat was blocking the Harriet II’s mooring, preventing the riverboat’s 227 passengers from disembarking and going about their lives.

The crew of the Harriet II waited 45 minutes for the pontoon boat to move. They broadcast instructions to the pontoon boat over the loudspeaker. According to passengers on the riverboat, those instructions were met with shouts and obscene gestures from the people on the pontoon boat.

This is the first place in the story where the race of the pontoon boat people becomes relevant. They were all white. It is fashionable among some willfully ignorant members of society to say that the pontoon boat people could have just been, well, assholes, and their race is not important. But I would argue that you simply wouldn’t see a handful of Black revelers preventing 227 passengers from disembarking from a commercial vessel for 45 minutes while the crew tried to cajole them to move. Black people know that if we tried that, we’d end up spending a night in jail, while our boat would be impounded at the bottom of the river. The people preventing the Harriet II from docking had to be white, because only white privilege inspires the kind of irrational confidence needed to hold up an entire riverboat full of people.

Eventually, the crew of the Harriet II sent first mate Damien Pickett, who happens to be Black, to shore in a smaller boat operated by a 16-year-old white kid. Pickett again tried to convince the pontoon people to move, and again they did not.

That’s about where the videos filmed by the Harriet II passengers pick up. The videos show the pontoon people arguing with Pickett, who tried to move their boat, and then one of the white men—who was shirtless, because of course he was—runs at Pickett and then shoves and punches him. At that point, Pickett throws his hat into the air (likely a signal to the boat that the situation had escalated and he needed back up), and a tussle ensues between the two men. But then another white man joins the fray and tackles Pickett to the ground. The two white men start hitting Pickett, and then a third white man joins in, and then a fourth. The 16-year-old white kid who ferried Pickett to the dock tries to intervene, and he is punched. There are two white women there, too: one who does nothing but watch the beating, and another who appears to be tugging at Pickett while he is on the ground.

When I showed the video to my children, this is the point where they recoiled. At the tender ages of 10 and 7, they already know enough to know how these things usually play out: The white people continue brutalizing the Black man, nobody stops them, and later I have to argue about how the white assailants should maybe go to jail after a weeks’ long trial where they cry about how afraid they were of the Black man they tried to lynch.

But not this time. This time, the white folks were committing their violence in full view of other Black people. This time, I got to tell my kids the old Mr. Rogers line: “Look for the helpers.”

Within moments of the start of the assault, the first Black man arrives on the scene, rushing down from above the docks, and is a peacemaker. He tries to pull the men off of Pickett, but is harassed by the white women. Concurrently, another Black person, a 16-year-old kid who was part of the crew of the Harriet II, jumps into the water and swims towards the docks to aid the crewman (the community has given this brother many loving nicknames: My favorites so far include “Aquamayne” and “Ja’Michael Phelps”). Before he arrives, additional Black people show up at the dock to aid Pickett. As the number of Black people grows, the pontoon people cease their attacks on Pickett. You can almost see their assumed privilege shrinking as the odds are evened.

Then the real melée breaks out. The white pontoon people continue to try to fight, but now they’re losing the battle. The white women who appeared to be part of the pontoon boating group try to join the fight, perhaps thinking their white woman–ness will shield them, and they are repulsed, largely by Black women who have by this point joined the fray. Eventually, the Harriet II is able to dock, and more Black people show up. One Black person grabs a folding chair and begins to use that to smite the man who first ran at Pickett. Eventually, he hits one of the pontoon women (who had already been handled by Black women) with the chair as well. The fighting continues even as the cops finally arrive. I imagine that in certain parts of white America, this is their nightmare: just a few bros out for a day of boating and beating up Black people, having their fun interrupted by more Black people than they can count using their fingers.

The fight broke down along largely racial lines—but I blame white folks for that. There were white onlookers, and riverboat passengers, who could have joined the defense of Pickett. Nobody was stopping them, but they declined to help. As happens so often in this society, Black people had to defend each other because nobody else will.

That is why this fight was so satisfying to so many Black folks: because this time we could help each other. That’s the teachable moment of the brawl; that’s the moral lesson I wanted to share with my children. Black people will stop white violence against us—much more quickly and effectively than law enforcement or the courts, sadly—if we are only given a chance to see the brutality before it’s too late. We will risk the legal consequences of our actions. We will put our personal safety on the line to free a fellow Black person from the clutches of violent white folks. We must. I promise you, every Black person who joined in the fight knew that one day, they might be Damien Pickett. Those folks weren’t defending a stranger; they were defending their future selves, or their children, or their friend.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →What happened to the pontoon people is what would have happened to George Zimmerman if he had attacked Trayvon Martin around anybody Black. It’s what would have happened to Gregory and Travis McMichael, had a boat full of Black people saw them chasing down Ahmaud Arbery. It’s what would have happened to Derek Chauvin, badge or no, if he hadn’t been flanked by armed accomplices, when he murdered George Floyd. Martin and Arbery and Floyd would all be alive if their killers had dared to try to hurt them in a place where other Black folks were free to help.

White people cannot kill us or brutalize us when we are surrounded by our own people. That’s why most of the videos you’ve seen or stories you’ve read about a Black person being killed or attacked by violent white folks share one key feature in common: isolation. They have to get us alone, catch us and take us away, or “create a perimeter” around us that cuts us off from other Black folks. They have to disconnect us from our community, because the community will not sit idly by and watch them destroy us.

What’s unique about this situation is that the white pontoon people really thought they could gang up on and beat the crap out of a Black person who was just doing his job, while a bunch of other Black folks looked on, as if those other Black folks wouldn’t do anything to stop them. I swear, those guys must have watched too many PragerU videos about fantasy enslaved Black people who are docile and obedient, instead of meeting actual Black people who have never once acquiesced to white supremacy nonsense, for them to think they could do this.

I am contractually obligated to mention that there will be legal consequences from the melée, of course. Three of the white men who attacked Pickett, Richard Roberts, Allen Todd, and Zachary Shipmen, have already been charged with crimes in connection with their assault. The police are apparently looking for other people involved in the fight, including the guy who swung the chair, for questioning. I imagine the chair-man, at least, will be charged (and I hope with every fiber of my being his defense is that he “feared for his life” and that, at trial, he takes the stand to say, “Yes they deserved to be hit with a folding chair, and I hope they burn in Hell,” before he takes the “L” and does three months in county lock-up where the other inmates treat him like a hero). The system is just not going to let a bunch of Black people defeat violent whites on video without finding at least a couple of Black people to throw in jail. America is going to America—you can count on that.

But I hope the Black people who participated in the Battle for Montgomery feel like it was worth it, regardless of the legal consequences. And not just because of the excellent memes. Their efforts were worth the legal price… because Damien Pickett is alive. If Pickett had met these particular white folks on a secluded dock, he might not be. If he had met them in the dark or too far away from his boat for anyone to see him, he might not be.

Black people are the helpers. Good lookin’ out.

Thank you for reading The Nation!

We hope you enjoyed the story you just read, just one of the many incisive, deeply-reported articles we publish daily. Now more than ever, we need fearless journalism that shifts the needle on important issues, uncovers malfeasance and corruption, and uplifts voices and perspectives that often go unheard in mainstream media.

Throughout this critical election year and a time of media austerity and renewed campus activism and rising labor organizing, independent journalism that gets to the heart of the matter is more critical than ever before. Donate right now and help us hold the powerful accountable, shine a light on issues that would otherwise be swept under the rug, and build a more just and equitable future.

For nearly 160 years, The Nation has stood for truth, justice, and moral clarity. As a reader-supported publication, we are not beholden to the whims of advertisers or a corporate owner. But it does take financial resources to report on stories that may take weeks or months to properly investigate, thoroughly edit and fact-check articles, and get our stories into the hands of readers.

Donate today and stand with us for a better future. Thank you for being a supporter of independent journalism.

Thank you for your generosity.

More from The Nation

Letters: Airline Deregulation, Interviewing the Cuban President, Human Resources at Human Rights Watch Letters: Airline Deregulation, Interviewing the Cuban President, Human Resources at Human Rights Watch

The industry-friendly skies… Cuba libre… Bosses are getting the boot, too…

A Year Under the Palestine Exception at Columbia University A Year Under the Palestine Exception at Columbia University

Columbia has tossed aside the mission at the heart of undergraduate liberal arts education: preparing student to be citizens in a pluralistic democracy.

Welcome to the Age of Psychedelic Inequality Welcome to the Age of Psychedelic Inequality

Psychedelic-assisted therapies have been hailed as the wave of the future. They’re also becoming big business. What if most people can’t afford them?

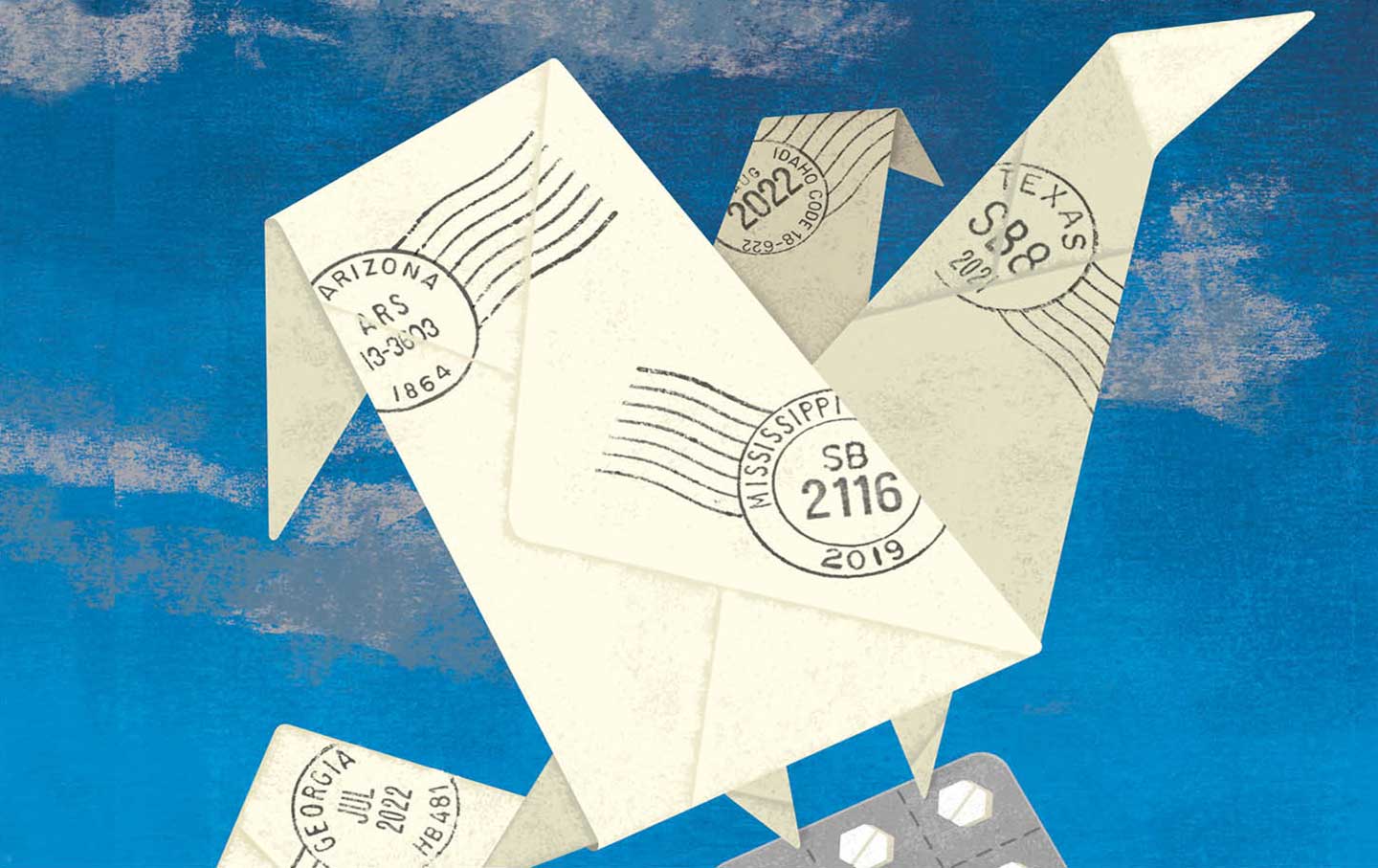

The Abortion Pill Underground The Abortion Pill Underground

Since Roe was overturned, thousands of people in red states have found a way to get an abortion—often thanks to providers operating at the edge of the law.

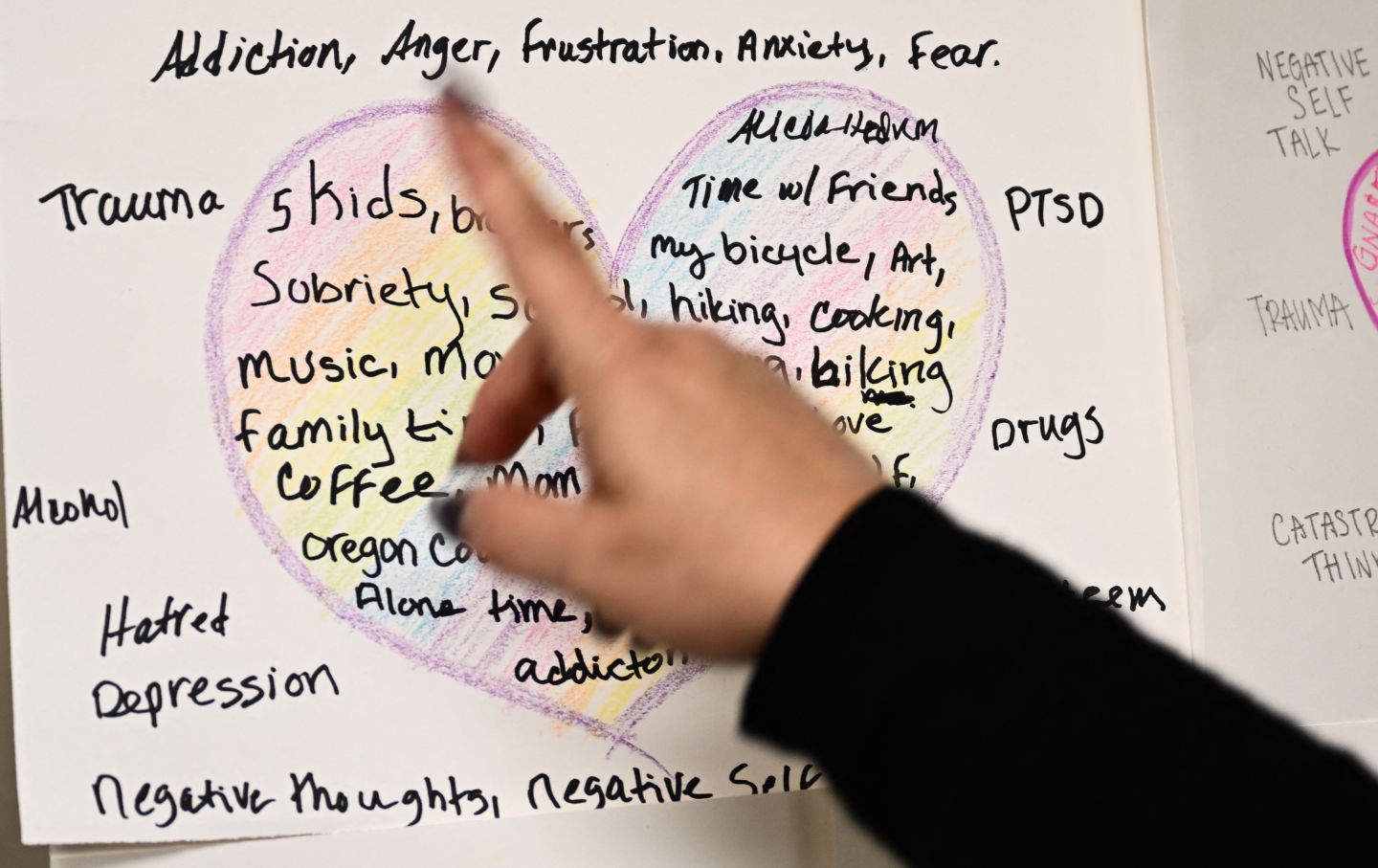

Oregon Revives the Drug War Oregon Revives the Drug War

The state’s landmark decriminalization initiative wasn’t given a real chance.

Abortion Bans Are “an Assault on the Practice of Medicine” Abortion Bans Are “an Assault on the Practice of Medicine”

Restrictive laws don’t just take away the right to choose, say physicians and ob-gyns, but also prevent proper treatment of pregnancies.