What Was the Cybertruck?

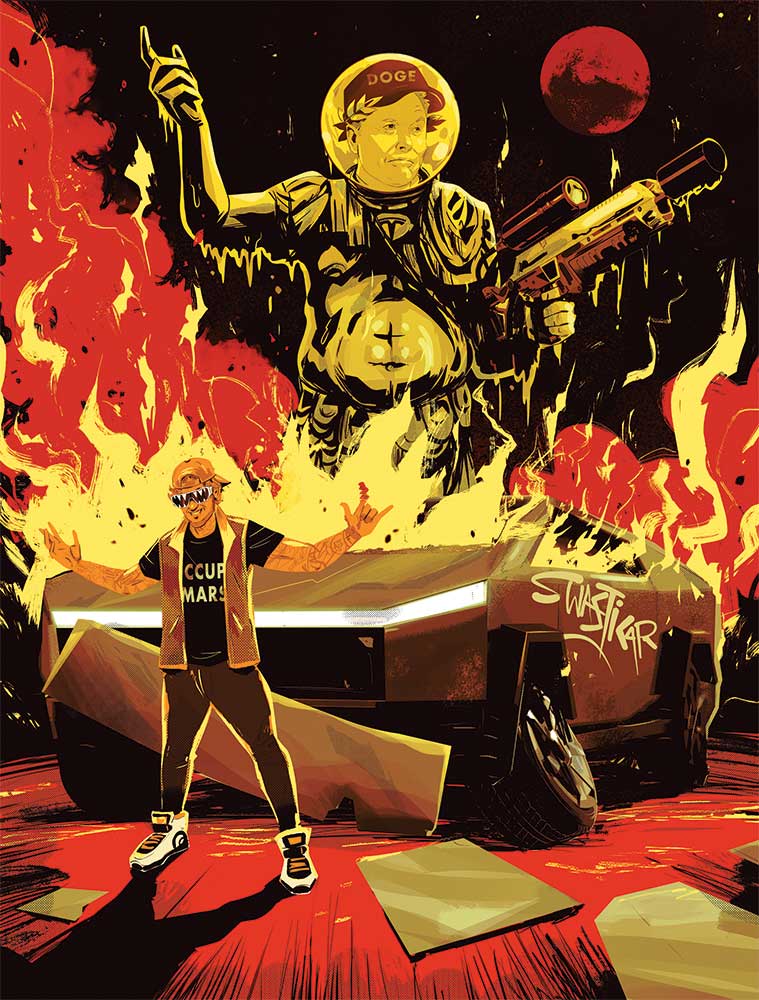

Elon Musk’s car from space offered a vision for a sustainable and autonomous future. All along, it was as awkward, easily bruised, and volatile as the entrepreneur himself.

What Was the Cybertruck?

Elon Musk’s car from space offered a vision for a sustainable and autonomous future. All along, it was as awkward, easily bruised, and volatile as the entrepreneur himself.

Ispot him from across the parking lot at the Indian Meadow Service Plaza in West Unity, Ohio. In the oppressive heat, his Tesla Cybertruck blends into the scenery, its shiny wrap shimmering in the sun like an oil slick. Clad in a bright-yellow T-shirt reading “DUCATI,” he appears to be genuflecting to his vehicle, as if pledging it fealty. When I look again, I realize he is doing squats in front of the Cybertruck’s windshield camera. I approach him—white, middle-aged, friendly-looking. He tells me he reserved his Cybertruck for purchase back in late 2019, shortly after its November unveiling in Los Angeles. What attracted him most to the vehicle, he says, was its unique appearance and its durability.

The latter claim strikes me as ironic. At that inaugural event in LA, Tesla’s chief designer, Franz von Holzhausen, tried to demonstrate that the truck’s windows were indestructible by throwing a metal ball at them—but ended up shattering the glass, twice. Over the next four years, with some 1 million reservation holders waiting in the wings, Tesla repeatedly pushed the Cybertruck’s launch date back, while its base price climbed from $40,000 to $61,000. The man I met at the Ohio rest stop was fazed neither by the truck’s polarizing design (which he approvingly called “obscure”) nor its skyrocketing cost. Having made his $100 deposit, he waited patiently for his car until Tesla called him in March 2024 to upsell him on the tri-motor model for an extra $1,000.

That August, his $120,000 Cybertruck “Beast” was finally ready, and he couldn’t have been more pleased (“I don’t like it—I love it!”). He is especially enraptured with the feature Tesla calls Full Self-Driving, which he believes is more skilled than “you, or me, or anyone.” He’s used FSD while drinking a cup of coffee and watching YouTube. I’m quickly reminded of Joshua Brown, the Navy SEAL who died in 2016 when his Tesla Model S, set to Autopilot, collided with a tractor trailer while he watched a Harry Potter movie on a portable DVD player.

I keep my questions short and superficial. At work is a lifetime of female socialization, which speaks against antagonizing strange men. But even more salient is my recent online experience with Cybertruck lovers—mostly male, right-leaning, and with some exceptions, fanatical and aggressive. It turns out that, like many consumer goods, the Cybertruck is less a physical object with clear use value than a symbol. But of what?

Despite its performatively tough appearance, the Cybertruck differs from other male-coded vehicles like the Ford F-150 or the GMC Hummer. The former, a gargantuan pickup truck, is a long-standing customer favorite; the latter, though a gas-guzzling emblem of excess, at least remained true to its hardy roots as the US military’s vehicle of choice during the Gulf War. What the Cybertruck promises goes beyond functionality or toughness: a vision of a smooth, sustainable, autonomously driven future, computerized for total convenience and security. Tesla’s marketing presents it as a kind of Mars rover, but with “more utility than a truck” and the speed of a sports car. A bingo card of stereotypically masculine wants and fears, it wraps excitement and uncertainty, danger and the possibility of conquering danger, pragmatism and fantasy, all into one fierce-looking metal package.

Since its release in late 2023, it has become clear that the Cybertruck’s reality does not live up to its image. Like Elon Musk himself, the vehicle is awkward, easily bruised, and disturbingly volatile—a professional promise-breaker. It can fall apart on the road or, worse, catch fire. Its short range might be impressive on Mars, where the rover’s longest trip was 28.1 miles, but not on Earth, where it is easily outperformed by other electric trucks like the Ford F-150 Lightning.

Despite empirical evidence to the contrary, the Cybertruck’s fans defend it as the greatest car ever made—some going as far as sending death threats on X to those who disagree. It is this refusal to learn from experience, whether one’s own or that of others, that I find to be the hallmark of the Cybertruck devotee. Ever ready to believe the hype, fans exhibit an almost religious devotion to their purchase, forgiving everything from harmless foibles (inconvenient door handles) to major flaws (a tendency for parts to fly off).

But perhaps we are all duped by something. A willingness to be conned as long as the illusion flatters our sense of self and our image of the future is a defining characteristic of our time. American culture has always favored snake-oil salesmen, but perhaps never more than in the era of Trump, America’s most successful con man. Under an administration that was backed, at least temporarily, by the world’s richest man—Elon Musk—the performance of innovation has become more important than the substance. The Cybertruck is today’s paradigmatic consumer object because it perfects the art of expensive disappointment, pushing buyers into ego-protecting delusion. To survive America in 2025 requires at least a little self-deception, if not about our cars then about the environment, politics, or the general direction society is heading. In a country run by scam artists, all that’s left is the illusion of autonomy and control. Why wouldn’t people gravitate toward a car that similarly promises, however falsely, to make them powerful and free?

My journey toward understanding the cybertruck as vehicle and concept began with a test drive. In April 2025, I visited a Tesla dealership in Manhattan’s Chelsea neighborhood, where I got behind the wheel of a dual-motor, all-wheel drive (AWD) truck. At the time, this model was one of three available variations, including a single-motor rear-wheel drive (RWD) and the tri-motor “Beast.” Compared to its RWD counterpart, which has since been discontinued due to low demand, AWD promises better traction and easier steering, although it lacks the accelerating power of the tri-motor version.

A car marketed as the pinnacle of futuristic ease, the Cybertruck is, per Tesla’s custom, devoid of traditional physical knobs and controls. Without these haptic conveniences, I am forced to rely almost completely on a single giant screen for all my driving needs. I soon notice another pitfall: There is no functional rearview mirror. Sure, the object itself is there, but as soon as you unroll the built-in tonneau to cover the truck bed—say, if it’s raining, or you’re transporting something that shouldn’t be exposed to the elements—the mirror becomes a useless black rectangle.

A logical fix would be a mirror-mounted rearview monitor, a product that was developed in the 1950s and has been readily available since the late 2010s. Adrian Clarke, who has designed cars for Land Rover and now writes for the car magazine The Autopian, tells me that this tweak would have been easy. A digital mirror substitute would maintain the Cybertruck’s futuristic vibe while respecting the design principle of heuristics—the idea that we, “as humans, expect things to be how we expect them to be.” For most products, adherence to heuristics is simply good customer service, but for a car, it’s also a safety issue.

The Cybertruck, meanwhile, funnels the entirety of the driver’s attention toward its central touch screen. This display, which looks more like an iPad than a typical automotive “infotainment” system, abounds with options and controls: temperature, suspension, speedometer, “mood lighting.” And if the cognitive load of managing all these inputs becomes too much, there is always FSD, the feature that most excited my Ohio rest-stop friend—but which, as I soon learned, is largely fantastical. If, as the owner’s manual suggests, “it is the driver’s responsibility to determine whether to stop or continue through an intersection,” why call it Full Self-Driving? In fact, few of Musk’s claims about the Cybertruck—from “wade mode” (which theoretically “allows Cybertruck to enter and drive through bodies of water, such as rivers or creeks”) to a bulletproof exterior, to pricing below $50,000, have fully panned out. But if the truck is not an aesthetic or technical marvel, a competent and well-priced utility vehicle, an ersatz spaceship, or a tool for surviving Mad Max–esque societal collapse, then what, exactly, is it?

Once I’m behind the wheel of a Cybertruck myself, I start to wonder whether the overwhelm is intentional, meant to push decision-making onto Tesla’s dubiously “autonomous” software. You can get in, adjust the air-conditioning, put on the perfect mood lighting, and let the outside world melt away. Through the gigantic screen, elements of physical reality, including pedestrians and other vehicles, are transformed into generic gray blobs tooling around on a grid. Inside this video-game-like pod, every other car—and every other human—becomes a non-player character.

The vehicle’s threatening exterior further encourages you to forget what you learned in driver’s ed about defensive driving. Ensconced within its “exoskeleton,” as Musk has called it, you get the distinct impression that caring about anyone else on the road is optional. In the United States, the Cybertruck has a five-star safety rating from the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA), part of the federal Department of Transportation. Yet this rating takes into account only those inside the vehicle’s metal carapace. In parts of the world where the safety of pedestrians, other cars, and drivers themselves is taken seriously, like the United Kingdom, Cybertrucks are banned—though individual enthusiasts have been caught driving them around anyway.

The American NHTSA rating seems suspect because the Cybertruck has structural problems that make it inherently unreliable. Its glued-on parts, from exterior panels to accelerator pedals, regularly malfunction, while its triangular design cuts off rear visibility and renders it less useful for the utility needs expected of a pickup truck, such as hauling or towing. It is also, apparently, quite flammable. According to a February 2025 report from the independent automotive blog FuelArc, the Cybertruck is “17 times more likely to have a fire fatality” than the Ford Pinto.

It’s no surprise, then, that nearly all extant Cybertrucks worldwide were recalled in March 2025 because, as Tesla put it, “the stainless steel panel of the cantrail assembly may delaminate at the adhesive joint, which may cause the panel to separate from the vehicle.” In layman’s terms, this means that the long, sharp-edged pieces of trim that divide the side windows from the windshield may detach and go flying at any time. Under the recall’s terms, Tesla will fix the cantrails on existing Cybertrucks for free, and new Cybertrucks will include a redesigned cantrail.

Recalls are not unusual in the automotive industry. But the Cybertruck’s flaws—even those that aren’t severe enough to prompt a recall—are different. Each new problem gives the lie to some specific marketing claim. It’s not just that the Cybertruck can’t be used as a boat; it also can’t go through a car wash without its warranty being voided. The metal panels on its exterior are so far from forming an “exoskeleton” that they fail even to stay put. And its electronic doors are not just inconvenient but actively dangerous: After a November 2024 crash in Piedmont, California, rescuers were unable to pry them open in time to save three of the people trapped inside.

Perhaps most embarrassingly, the Cybertruck cannot perform anything like Full Self-Driving. I learn more about this feature’s limitations on my second test drive, this time in an ultra-powerful Beast. My chaperone riding shotgun, a Tesla sales associate named Imran, proposes that we drive to the IKEA in Brooklyn so I can experience FSD in both city and highway conditions. As we set off, I discover that the feature has three modes: Standard, Chill, and Hurry. According to the owner’s manual, “Chill provides a more relaxed driving style with minimal lane changes,” while “Hurry drives with more urgency.” But is “Hurry” demure and mindful enough for real-world use? Echoing Tesla’s marketing copy, Imran tells me that although FSD is completely reliable, it falls to the driver to supervise in case it “tries something funny.” The owner’s manual agrees: “In rare cases, Full Self-Driving (Supervised) may not appropriately slow down, come to a stop, or resume control for a stop sign or traffic light.” Like boring old cruise control, FSD leaves the executive functioning to our puny human intelligence.

Tesla’s advertising repeatedly gestures toward this gap between theory and practice. If the name “Full Self-Driving (Supervised)” is already a bit of a letdown, an advertising e-mail from June 6 is even more equivocal, inviting customers to “Let your Cybertruck do the driving. With Full Self-Driving (Supervised) engaged, your Cybertruck can steer [and] respond to traffic signs and change lanes for you, under your active supervision.” This unexciting promise, which one imagines teams of lawyers systematically defanging, ends with an asterisked warning, printed in minuscule text below the ad: “Requires active driver supervision at all times and does not make the vehicle autonomous.”

As we approach the IKEA parking lot, Imran describes another putatively autonomous feature called “Summon.” Summon is supposed to allow me to live my dream of instantly forgetting where I parked and never paying the price. I can load up on SNÅRSVARDs, emerge from IKEA blissfully unaware of my car’s location, and Summon it to my side with my phone. I express unfeigned enthusiasm, whereupon it turns out that Summon is not yet available for the Cybertruck—although it does exist for the Tesla Model 3, as Dumb Summon and Actually Smart Summon (ASS). Online, people have speculated that Cybertruck’s very own ASS may be right around the corner, but as of late June 2025, even die-hard fans were beginning to lose hope.

Undeterred by our tragic lack of ASS, I watch in wonder as Imran demonstrates the Cybertruck’s adaptive air suspension. This feature can lower the car to almost-normal-person height—although children and short kings will still need to clamber—or raise it to hop-on-crushing levels. Unprompted, my companion points out that at its tallest, the truck makes it impossible for outsiders to get in. I ponder possible uses for such a feature in our pre-apocalypse world and come up empty. Post-apocalypse is a different story: It’s heartening to know that if roving bandits try to breach your Tesla-branded pseudo-tank, it can be made impenetrable—except to rain.

As we make our way back to the Tesla dealership, Imran invites me to try out Beast mode, which lets the Cybertruck accelerate from 0 to 60 in a stomach-churning 2.6 seconds. After we’ve peeled out several times on the Brooklyn cobblestones, I ask him why he thinks people buy these things. Is it because they’re fast, because they’re supposed to be able to off-road, because of FSD? “A lot of people don’t just drive a car to get from point A to point B,” he replies. “Personally, I use what I drive to represent the personality of me.” As I would soon learn, the Cybertruck’s ability to make its owners identify with it is perhaps its greatest success.

The Cybertruck’s short history dates back to the mid-2010s, when Musk was still posing as an apolitical tech disruptor rather than a MAGA-aligned oligarch. It took Tesla engineers until November 2019 to transform Musk’s original vision of a Ford F-150-style “supertruck with crazy torque, dynamic air suspension, [that] corners like it’s on rails,” into a demonstration-ready prototype. Despite the window-smashing debacle at the unveiling, Tesla began planning for a projected release in late 2021. Then, in October, the company quietly removed the Cybertruck’s specs from its website—without, however, ceasing to take deposits. The launch was postponed to 2022, then to late 2023. In the meantime, Cybertruck hopefuls outside North America learned that they were out of luck—at least at first (after being sold exclusively in the United States, Canada, and Mexico for nearly two full years, the Cybertruck recently launched in South Korea and the United Arab Emirates). Another downgrade was the promised battery life, which was reduced from a fanciful 500-mile range to a more realistic 340, although some real-world users have reported numbers closer to 200.

Before customers ever saw their Cybertrucks, Tesla had already performed a textbook bait-and-switch. Once it was delivered, it turned out that the truck’s most “futuristic” attributes, from FSD to ASS, either didn’t work or merely rehashed earlier creations. Its stainless-steel construction, for instance, recalls the DeLorean, made famous in Back to the Future after its maker went bankrupt in 1982. The Cybertruck’s pyramidal form is another ’80s throwback. From the outside, it resembles the wedge-shaped Citroën Karin, a concept car that made a splash at the 1980 Paris Motor Show but was never mass-produced. According to Clarke, the Cybertruck is a “mishmash” of dated influences that “call back to an imagined 1985.”

Beyond its technological and aesthetic problems, the Cybertruck is burdened with political baggage. At that Ohio rest stop, I’d asked my new friend if he was bothered by Musk’s brief association with Trump. He smiled: “It doesn’t bother me, because I’m a Trump guy.” Besides, back in 2019 when he reserved his Cybertruck, “Elon Musk was more for the left” than for MAGA, he said. Regardless, his decision to buy a Cybertruck wasn’t political. He doesn’t care about politics or EVs but about aesthetics and functionality, both of which his Cybertruck delivers in spades. After thinking for a minute, he added, “I’m in the middle. You know, I like a little bit from the left, I like a little bit from the right. I wasn’t a fan of Kamala, but it is what it is. Everybody has their own opinion.”

Since the Cybertruck first went on sale in 2023, responses to it have become increasingly polarized. People have defaced parked Cybertrucks with graffiti or bumper stickers that say things like “Swasticar,” which owners have tried to preempt with bumper stickers of their own. In a few cases, anti-Musk sentiment has escalated to all-out physical attacks and even Cybertruck-mediated terrorism. At my first test drive, a Tesla rep told me that haters merely “bring more attention to the brand,” thereby, presumably, boosting sales. This statement may apply to Tesla, Musk, or even Trump, but not to the Cybertruck, which has proved to be a worse flop than the Ford Edsel. According to Forbes, the Edsel hit just 32 percent of its projected sales target when it debuted in 1958. Judging by the number of vehicles affected by the March 2025 cantrail recall (about 46,000), Musk’s claims of 1 million Cybertruck reservations and 250,000 projected annual sales also did not materialize.

These and other failures, however, have not shaken the loyalty of the Cybertruck’s most ardent fans. Nowhere is the gap between its lackluster performance and its mythic image more apparent than on the forums of the Cybertruck Owners Club, which I briefly joined in hopes of finding owners willing to tell me about their experience. Instinctively, I chose a male pseudonym, “Bob Jones,” which I naïvely thought might help me avoid backlash. “Hi everyone,” I wrote. “Any current or former Cybertruck owners out there willing to talk to me, a writer working on an article about the cultural impact of the vehicle?” The responses were swift and merciless: GIFs of eye-rolling or disgusted grimacing, followed by calls to “GO AWAY” and “SUCK IT.”

But then, almost despite themselves, posters began feeding me information. One person suggested I worry less about the Cybertruck as a cultural phenomenon and more about its impressive technical attributes. When I said I’d test-driven a Cybertruck and found the experience odd, I was told that “it doesn’t take more than a 15-year-old with a learner’s permit” to understand that the Cybertruck “is the greatest vehicle ever conceived.” Even after multiple users pointed out that the thread’s hostility could itself become part of my story, the posts kept rolling in. Many praised Tesla and Musk (“Tesla is making awesome vehicles and is almost single-handedly changing the world”; “the Cybertruck is the best vehicle I’ve ever owned”). Another user wrote that they had considered their 2015 Tesla Model S “the best *anything* [they’d] ever bought” until they purchased a Cybertruck, with the caveat: “As long as the stainless steel panels stay glued.”

A few enthusiasts were able to acknowledge that the Cybertruck could be annoying to drive because it attracted negative attention, although blame was generally placed on the finger-pointers and vandals. Critics were dismissed as proverbial blue-haired “libs” or vilified for unfairly targeting what, at the end of the day, was just another consumer product. “If I only purchased from corporations whose CEOs shared my values,” someone wrote, “I’d be raising barns with the Amish and making my own pants.” A few users rejected the very idea that the Cybertruck was a controversial car to own. “The controversy,” one wrote, “is a fabricated construct perpetuated by click-driven media who make a living stoking fear, anger and anxiety.”

Over the next few days, demands that I dox myself became frequent and combative. Unsolicited advice about what I “should” be writing about instead of the Cybertruck grew more pointed. Soon, the Cybertruck-owning brethren were attacking one another, duking it out with memes when words proved insufficient. The discussion quickly turned political, until eventually one user speculated that “Bob Jones” was none other than Elon Musk himself.

If we think of the Cybertruck as a means of self-expression, the gulf between its shoddy workmanship and its cultlike fan base starts to make sense. Even those who complain about aspects of the truck’s performance, from its tearaway panels to its dearth of ASS, seem eager to demonstrate their loyalty to the project as a whole. It’s hard to admit you’ve been had, especially if you’ve spent more than $100,000 on a famously depreciating asset.

Eric Noble, a car design expert and professor at ArtCenter College of Design, has called the Cybertruck a “failure of empathy”—that is, a failure by Tesla to think about what the typical pickup truck driver might actually want or need. But the Cybertruck lover’s devotion represents a further failure of empathy—this time toward themselves. The Cybertruck Owners’ Club forum, whose most active users seemed willing to drown their doubts in the soothing ocean of groupthink, reminds me of the viral video of a guy blithely sticking his finger in the Cybertruck’s “frunk” as it closes. He is confident that built-in sensors will stop the car from mangling him, but instead it breaks his finger. To me, the most telling part of the video is not the climax but the preamble: Before placing his finger in the truck’s maw, the man tries the same thing with a stick—and watches as the frunk breaks it in half. Yet so profound is his faith in Tesla engineering that he disregards his lying eyes and forges ahead with the blood sacrifice.

Initially, I wanted to class the Cybertruck alongside other products whose hostility to the user becomes a badge of honor for a particular kind of rich person. The foot-deforming Louboutin pump or the over-collagened pout is a form of conspicuous consumption that is at once aggressive and self-defeating. “Behold my latest purchase!” the late-capitalist masochist seems to say. “I have spent a small fortune on something that not only brings me no enjoyment, but actively harms me. Take that, peasants!” But the more I learned about the Cybertruck, the more I understood this effect—hostile architecture, but make it fancy—to be a happy accident.

The Cybertruck was not intended to be unwieldy and repellent, but had that greatness thrust upon it. A billionaire’s vanity project, it substitutes a projection of Musk’s specific enthusiasms for more robust measures of consumer desire—and, at least among Tesla fans, totally gets away with it. For today’s techno-oligarch, the ability to force one’s idiosyncratic tastes down the public’s throat is the ultimate prize. To paraphrase the old Yakov Smirnoff bit, in post-neoliberal America, product buys you.

This dynamic is the result of decades of market manipulation. Before the Cybertruck existed, Tesla was already thriving in the hype-driven economy that emerged in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis. This was the hopey-changey moment of Obama’s first term, when people eagerly bought into the idea of corporations with a social conscience. An important element of Tesla’s early success was, accordingly, “emissions laundering,” in which EV companies sell regulatory credits to traditional automakers trying to avoid emissions fines. In March 2013, five years after Musk became Tesla’s CEO, the practice helped the company post its first-ever profits. By July, it had earned admission to the Nasdaq-100, where it replaced Oracle, the multinational technology conglomerate. Tesla then became embedded in myriad Nasdaq-pegged funds, which further boosted its circulation and caused its stock price to surge by 400 percent in just six months.

Despite its origins in pure speculation, this kind of “growth” has granted Tesla permanent leeway among so-called market experts. Even in Musk’s DOGE era, with Cybertruck owners selling their cars or plastering them with defensive bumper stickers, Wired reported that analysts don’t treat Tesla like other automakers, because its on-paper value is “multiples higher than companies that sell more cars.”

In light of these triumphs, it may be tempting to see the Cybertruck as a mere misstep for an otherwise pathbreaking company ushering in a bold, metallic cyberfuture. After all, even with Chinese competitors like BYD catching up, Tesla claimed a larger global market share than any other EV maker in 2024. Beyond this tangible reality lies the fact that, as the Financial Times wryly put it, “Tesla is not a car company, but it does a good impersonation.” The lion’s share of its $750 billion valuation “hangs on things that are yet to exist,” from self-driving robotaxis to humanoid helper robots, and its devoted fan base believes each new ruse.

In early 2025, amid plummeting profits and Musk’s brewing tensions with Trump, the CEO was reportedly seeking to redefine Tesla as an AI firm rather than an automaker. But was it ever an automaker in the first place? Since 1999, when Musk began the series of investments that would make him the richest man on earth, he has made a habit of “entering an ultracomplex business and not letting the fact that he knew very little about the industry’s nuances bother him,” writes Ashlee Vance in his biography, Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic Future. One reason this strategy has been so successful is that, over the past several decades, the US economy is now increasingly financialized. In other words, its underlying industries—whether cars, solar panels, or online payment processors—have become vastly less important than the financial instruments used to manipulate them. By 2008, Tesla had come to resemble many other American companies in that, as Liz Franczak and Brace Belden’s podcast TrueAnon explained, “it is mostly a stock company that also sometimes, allegedly, produces things.”

Their feud aside, one affinity between Musk and Trump is their skill in spinning purse-string-loosening tall tales. Trump, of course, has now twice convinced enough people that he can “Make America Great Again,” the realities of his rule notwithstanding. Writing in Salon back in 1999, Mark Gimein described Musk’s image as that of “the lucky guy” about to lead hangers-on to “the big score.” From early on, the entrepreneur’s greatest talent lay in “[making] his backers believe that he is the Brand X, the next superstar.”

It may seem mysterious that Musk continues to be heralded as an entrepreneurial wizard despite failures like the Cybertruck. One possible clue lies in what tech analyst Mike Ramsey, speaking to Wired, has called a “reality distortion field” surrounding Tesla. As Walter Isaacson recounts in his Musk hagiography, when it came time to craft the Cybertruck, the CEO’s overwhelming desire to “build something cool” overrode the “few dissenting voices suggesting that something too futuristic would not sell.” Musk allegedly concluded one brainstorming session by saying, “I don’t care if no one buys it,” a sentiment that extends to many parts of his business empire. Writing for The Drive in 2018, Edward Niedermeyer observed that, “at its core, the Tesla phenomenon is a cultural one,” based not in quality or profitability but in “a story that millions of people have chosen to believe.”

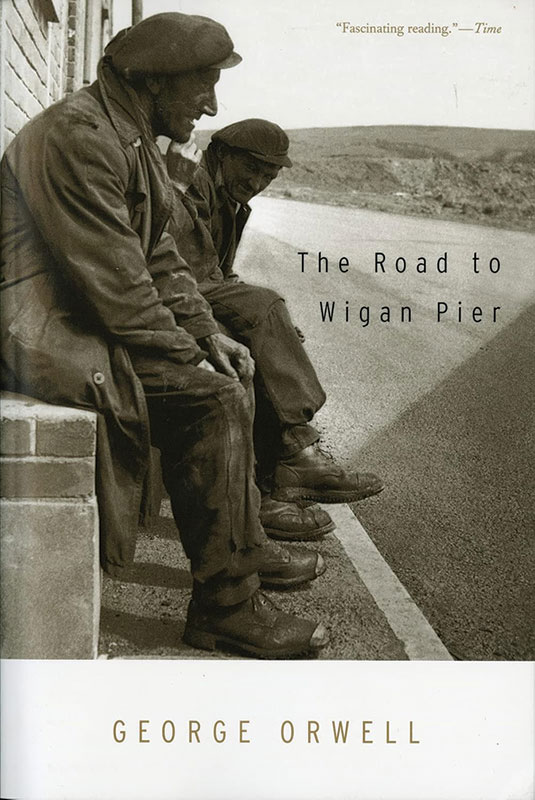

When Trump was elected to the White House in 2016, and again in 2024, Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four enjoyed a sudden increase in sales. But an earlier, lesser-read Orwell title may be more relevant to our condition of right-wing techno-oligarchy: The Road to Wigan Pier. It is astounding to open a book from 1937 and discover that, long before the advent of grocery store self-checkout, AI customer “service,” and TikTok brain rot, it was already apparent that technologizing everything in sight would “make a fully human life impossible.” Superimposing categories like “artificial intelligence” or “techno-optimism” onto Orwell’s text gives a precise description of how tech boosters think about their preferred ideology of post-singularity abundance: “Machines to save work, machines to save thought, machines to save pain, hygiene, efficiency, organization, more hygiene, more efficiency, more organization, more machines,” until, at last, we arrive at what Orwell calls “the paradise of little fat men.”

It’s now 2025, and while we seem to be hurtling at full speed toward the terminus Orwell described in Wigan Pier, we are still some distance away. And yet, we are constantly bombarded with strident techno-futurist propaganda that demands allegiance to automation for its own sake. This is the Cybertruck’s native clime: Here is a vehicle that looks designed to crush enemies in an inhospitable environment. It is a mobile panic room, a place to make you feel strong when you are weak. At the same time, it nudges you to accept that, however strong you may be, you cannot surpass the machine. So why try?

Gesturing toward both the future and the past, the Cybertruck betrays a contradiction at the heart of the technological advancement Elon Musk pretends to represent. As Orwell wrote, while the dream of progress is to create an environment that is “safe and soft,” attaining it requires a “striving to keep yourself brave and hard.” This means that the “champion of progress” is “at the same moment furiously pressing forward and desperately holding back,” like an imaginary “London stockbroker” who goes to his office “in a suit of chain mail” and “insists on talking in medieval Latin.” The Cybertruck, too, imprints buyers with the tech oligarchy’s backward-looking tastes—not only for Blade Runner, but also for ancient Rome and monarchism. To drive a Cybertruck is to partake in the fantasy of a premodern lawlessness in which the mightiest warlord made his own rules, unencumbered by legislation or moral stricture.

The truck’s most impressive feats have nothing to do with appearance, functionality, or even Tesla stock. Slotting itself seamlessly into an already intensely polarized political discourse, it has made getting scammed feel like an achievement. Tesla fans become willing marks who mistake their gullibility for enlightened contrarianism. In the end, what the Cybertruck’s owner purchases is not the car itself, or even a sense of rugged individualism, but a tiny share of the scam economy. A simulacrum of a car produced by a simulacrum of a car company, the Cybertruck is perfect for this mask-off moment in our culture, when the titans of American politics and industry have stopped even pretending to care about the common good. Its faux-bulletproof exterior and pretend-high-tech innards exude contempt not for the human being as consumer—although it is certainly an object lesson in caveat emptor—but for the human being as such.

More from The Nation

The Disturbing History of ICE’s “Death Cards” The Disturbing History of ICE’s “Death Cards”

The Vietnam-era practice is yet another example of ICE agents thrilling to the brutality they have been encouraged to cultivate.

The Red State–Blue State Healthcare Divide Is Dangerous for Everyone The Red State–Blue State Healthcare Divide Is Dangerous for Everyone

Whether or not you have access to independent, scientifically sound public health guidance may depend on how your state voted for governor.

The American Universities Programming Israel’s Killer Drones The American Universities Programming Israel’s Killer Drones

Industry partnerships in higher education are pushing STEM graduates into the business of weapons manufacturing and genocide profiteering.

In the Trump Era, Celebrating Black History Month Feels Radical Again In the Trump Era, Celebrating Black History Month Feels Radical Again

After putting on their very best performances of solidarity every Black History Month, this year corporate marketers have seemed at a loss for words.

ICE’s Detention of Pregnant People Continues a Disgraceful American Tradition ICE’s Detention of Pregnant People Continues a Disgraceful American Tradition

We are seeing yet another example of state-sanctioned violence against the reproductive futures of those deemed outside the national body.

The Price of Being Black and Proud in European Soccer The Price of Being Black and Proud in European Soccer

The Brazilian star Vinicius Jr. has repeatedly been a victim of racist abuse from soccer fans. Now, it seems such vitriol can even come from players without much consequence.