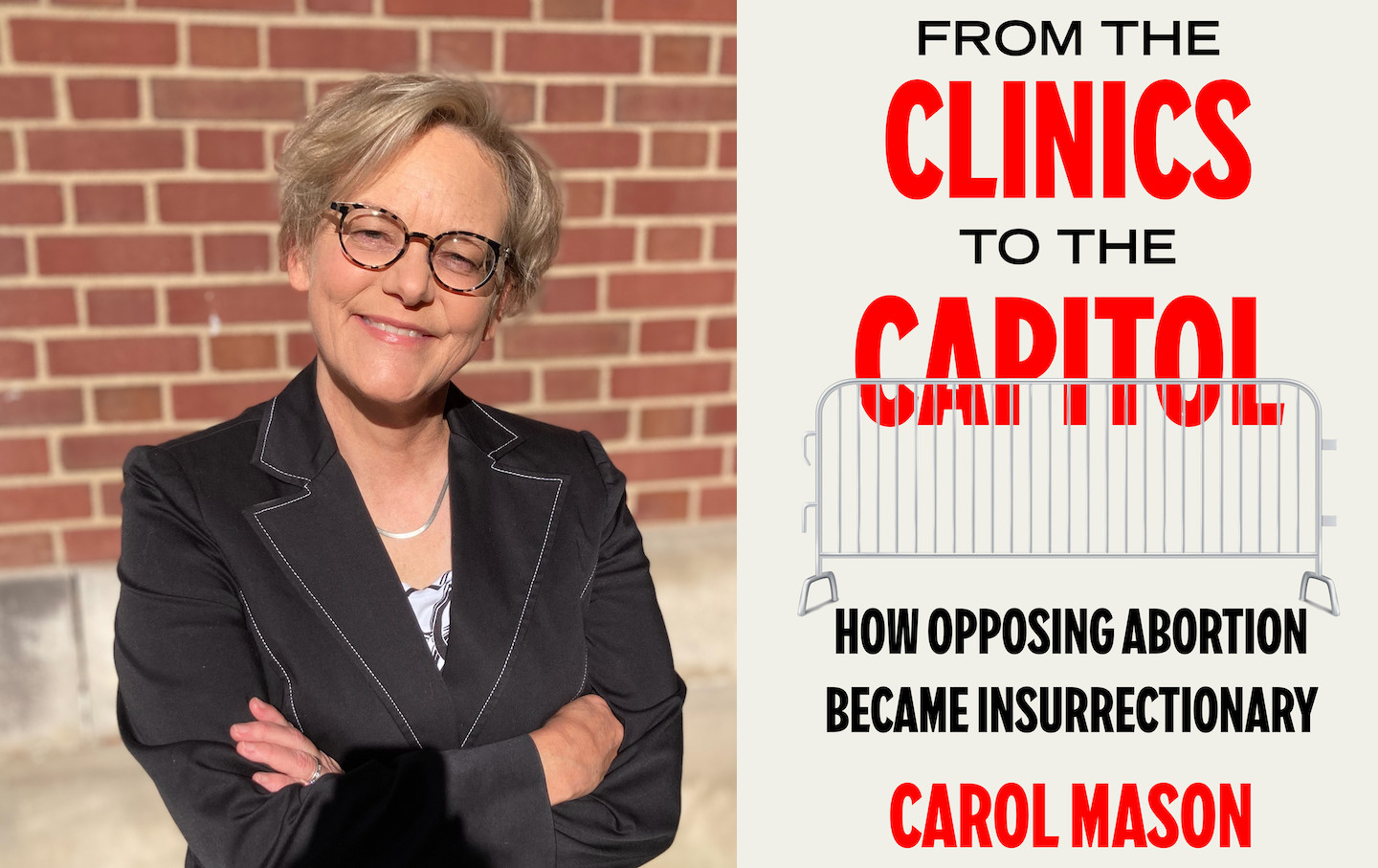

Carol Mason Explains How Abortion Opponents Went From Blockading Clinics to Storming the Capitol

A conversation with the author about her new book, From the Clinics to the Capitol: How Opposing Abortion Became Insurrectionary.

After Trump supporters stormed the Capitol on January 6, 2021, Carol Mason, a scholar of right-wing movements, received a text message from her sister. “How could this have happened?” Mason’s sister asked. “I don’t know how this happened.” Mason texted back: “I do.”

For decades, Mason had studied writings by anti-abortion and right-wing extremists who fantasized about taking down the federal government. Her first book, Killing for Life, traced how these extremists went from blockading clinics to bombing and shooting abortion providers in the 1990s. After getting her sister’s message, Mason realized she had the subject for her next book: how the history of the anti-abortion movement shed light on what happened that day at the Capitol. The result is From the Clinics to the Capitol: How Opposing Abortion Became Insurrectionary (University of California Press).

I spoke with Mason shortly before the book’s release in August. Our conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

—Amy Littlefield

Amy Littlefield: Tell me what it was like for you, as a scholar of right-wing movements, and the anti-abortion movement in particular, to watch the attacks on the Capitol on January 6. What did you register about that moment, given your expertise?

Carol Mason: In the book, I write about that moment where the rioters are attempting to come into the barricaded doors of the [Senate] chamber. I was looking over the shoulder of my partner at her computer, and I literally had to sit down because I felt faint. As I write in the book, this was simultaneously unprecedented and extremely familiar to me because of all the readings I’d done over the years. It was at that point where everything fictionalized or fantasized about [by right-wing and anti-abortion extremists]—like gunning down Congress—I could see [how it could] happen very easily. I swooned and not in a good way.

I write in my book that a lot of the emphasis in the reports on January 6 was on white nationalists and theocratic Christians and Proud Boys and other far-right militant groups, while the anti-abortion folks [who were also there that day] went by the wayside. I look historically, to answer the questions that are implied in the subtitle of the book. How did opposing abortion become insurrectionary? How did abortion opponents come to name the federal government as their enemy? How did they come to participate in armed assault on the Capitol and on lawmakers? For example, we had the political assassinations in Minnesota at the beginning of the summer. How did those who oppose abortion also come to take up arms against the lawmakers and oppose the rule of law?

AL: So how did you go about answering that question? How did abortion opponents come to view the federal government as the enemy and how did they come to oppose the rule of law?

CM: I looked at primary source materials [including] the Army of God manual. This was a manual that was written in the early 1990s or late 1980s [and] was meant to be underground. It was unearthed, quite literally, because it was buried in the backyard of Shelley Shannon, who tried to assassinate [Kansas abortion provider] Dr. George Tiller in 1993.

There are whole sections of that manual that aren’t on the Internet, and part of the reason for that is because they tell you how to build incendiary devices [and] bombs. The manual really charts out the thought system that the militants had. They started off with a kind of “rescue” mentality, [the idea popularized by the group Operation Rescue that you can “rescue” unborn babies by blockading abortion clinics], then at the end of that manual, there’s a declaration of war. And it’s not a declaration of war against abortion providers; it’s against the federal government. And there’s another shift [where] they talk about taking up arms. It is a shift in tactics from sabotaging, blockading, and bombing abortion clinics to the idea of homicide with guns and, ultimately, armed insurrection.

Another revelation I had when I looked at that manual again: I realized that there’s a whole section that basically provides a theological argument for why using misinformation—in other words, lying—is OK for a Christian soldier to do. That, I think, is something that we really need to pay attention to as we’ve shifted in the 21st century to a sort of wholesale disregard of the facts.

AL: I want to ask you about the crossover you see between the white nationalist movement that gets the most attention for their role in the Capitol attack and the anti-abortion movement. You describe them as parallel and sometimes intersecting movements, and you write: “I believe that white nationalism had for decades been making inroads into the American imagination under the guise of opposing abortion.”

CM: It’s not to say that all people who see themselves as pro-lifers—or who have a stance against abortion for religious reasons—it’s not at all to paint them broadly with one brush that denigrates them as racist. In fact, I explicitly write early in the book that I’m not saying all pro-lifers are white supremacists. I look at particular people who were involved in both anti-abortion and militant supremacist groups. I look at the shared tactics that they had, and I look also at the common narratives or imagery they shared.

I look explicitly in Chapter Four at two people. One is Eric Rudolph, and the other is Paul deParrie. Eric Rudolph, a convicted felon, fatally bombed [abortion clinics, a lesbian bar, and the site of the 1996 Olympics]. I look at his prison writings. I really wanted to see how he was answering and engaging this question of race and racism. He specifically says, “I’m not a racist. I’m not a white supremacist.” Yet he deploys all this language and all this argumentation that completely connects with and replicates white nationalist arguments. I also found out that at one point between bombings, he actually went out west to one of the most notorious enclaves of white supremacists. (That was revealed by journalists who have a new podcast on Rudolph, American Shrapnel.) This updated research on Rudolph helps to solidify the crossover among far right and antiabortion thought.

In my book I provide a rather close reading of Rudolph’s novel, All Enemies, Foreign and Domestic [which he wrote while in prison for his bombings]. One aspect that I found interesting was that his chief villain was not an abortion provider—although he has plenty of anti-abortion sentiment in the novel—but his chief villain is a transgender person. Even in jail, Rudolph was keeping up to speed with the evolution of right-wing demagoguery.

I also look at Paul deParrie, who’s a great contrast to Eric Rudolph, because he doesn’t bomb anybody. He doesn’t shoot anybody. His power is the power of the pen. He was a publisher of Life Advocate magazine, based in Oregon. He was very chummy with groups who saw the Pacific Northwest as a white bastion. I write about him as a go-between between extremist groups and conservative groups. He wrote journalistic pieces in newsletters and magazines, but he also wrote novels that helped radicals envision anti-abortion violence. He was also involved with Neal Horsley’s website, The Nuremberg Files, which I see as an early digital version of doxing, basically. It was a website that put up names, addresses, and personal information about abortion providers. When one abortion provider was killed, their name on the website appeared with a strikethrough—a line drawn through their name as if checking off things on a list. This was a precursor to the doxing that we have now, and it was reflective of the kind of leaderless resistance idea that had become standard in the militia movement and among white supremacists. In this way, my book is providing the historical and textual evidence that there was a borrowing of ideas and tactics of radicalization [across the anti-abortion and other militant movements] that we now see in the mediascape of the far right.

AL: One of the main takeaways from your previous book, Killing for Life: The Apocalyptic Narrative of Pro-Life Politics (Cornell University Press 2002) is how anti-abortion activists have used apocalyptic rhetoric that frames the fight against abortion as a holy war that could bring about the end of the earth. Can you talk about how that narrative has evolved?

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →CM: Let me start with the apocalyptic thinking as I saw it happening in the ’90s and wrote about in Killing for Life as opposed to what I see it doing now. The idea of “apocalypse” is not simply saying that this is a holy war. A big part of it is to see your opponents as enemies. In this thinking, abortion is not a policy issue in which you might have a political opponent, but it’s really a war in which you have an enemy in a zero-sum cataclysmic conflict. In Killing for Life, I argued that apocalypticism was what militant and mainstream abortion foes shared with each other and with right-wing groups like white power and Patriot militias. They shared a sense of time running out, a sense of imminence. Their aims and ideologies might be a little bit different, but they were all amped up. They were preparing for a fight of world-ending proportions.

In the twenty-first century, the apocalyptic framing is not just about having diametrically opposed enemies, and not only a sense of time running out, but the whole temporality of it has changed. Whereas we may have been preparing for something big in the ’90s—you know, we need to stop abortion now, because Jesus is coming or because God would lift his veil of protection—now, I think the idea is that the apocalypse is here, it is happening. Many January Sixers saw their actions as an extension of the American Revolution, an ongoing past-in-present. They see the apocalyptic battle now as one in which they’re playing a part today, not preparing for it tomorrow.

AL: Can you talk about your decision to write in the first person with this book? It was striking to see an author include personal anecdotes in a serious, academic book. And you didn’t write in the first person with Killing for Life.

CM: I teach [at the University of Kentucky] and I realized that my students don’t know anything about the radical, militant anti-abortion movement that resulted in bombings and killings in the ’90s. My editors and I discussed that we wanted this to be more of a trade book than an academic book. We tried to figure out what kind of voice I wanted to cultivate for that.

I worked with a talented editor, Jim Berg, who analyzed my writing and said, “Look, this part is really academic. You need to have a PhD to understand this part. And this part is really flowing well.” We went in the weeds, like: “This sentence you have on Mildred Jefferson, that could be four sentences.”

One thing that somebody who’s read it has told me is that the personal anecdotes act as a release valve. Everything is so heavy and terrifying that to have that little levity gives the reader some breathing space before they move on to another set of intense primary materials and my analysis of them.