How Trump’s Immigration Crackdown Chills Organizing and Erodes Conditions for All Workers

How Trump’s Immigration Crackdown Chills Organizing and Erodes Conditions for All Workers

When one group of workers is terrorized or disappeared, it threatens all workers’ ability to fight for their labor rights.

Workers with SEIU Local 26 and UNITE HERE Local 17 marched and rallied at the Minneapolis-St. Paul airport alongside community members on December 3, 2026. They were for an end to deportation flights conducted by private companies such as Signature Aviation.

(Amie Stager)In late 2025, federal immigration authorities detained a nonunion janitor who had recently—and publicly—accused contractors for Minnesota’s Ramsey County of mass wage theft. “Despite a bunch of intimidation and threats to his job by his nonunion employer, who was trying to pay less, he came forward at a press conference launching these allegations,” Greg Nammacher, the president of SEIU Local 26, told me.

The courage of this worker, who has been released but is now in deportation proceedings, played a vital role moving the case forward, according to the union, and it supported a similar wage theft case against Hennepin County contractors, which was also announced at the press conference where he spoke. The effort delivered for workers. The case against Hennepin County contractors resulted in the disbursal of nearly $400,000 in back pay to more than 70 subcontracted workers in December 2025, and the case against Ramsey County contractors is ongoing and has already led to some internal policy changes.

When someone who fought so successfully for workers—both immigrants and non-immigrants—is detained, “it sends a chill through all the workers in the nonunion companies that are trying to stand up and get their rights enforced,” Nammacher said. (I am not sharing the identity of the worker, to protect the privacy of his loved ones.) “When the workers who are stepping up to try and reveal violations are silenced, the standard comes down for the whole industry.”

The Trump administration claims that its crackdown on immigrants will protect the jobs of American workers. “When foreign-born workers depart, then it creates jobs for people who are native-born,” National Economic Council director Kevin Hassett said in December 2025. White House spokesperson Taylor Rogers said earlier this month that “President Trump has done more for American workers than any president in history by cracking down on visa program abuses, successfully negotiating new trade deals, securing our border, and carrying out the largest mass deportation of illegal aliens.”

But the administration’s escalation of immigration enforcement, through mass deployments of masked, armed federal agents to cities and their surrounding suburbs, is creating hostile and stressful environments for all workers, not just immigrants, labor leaders say. Federal agents abducted an educator trying to ensure safe dismissal at a high school in Minneapolis. They chased a day laborer at a Home Depot in Southern California onto a freeway, where he was hit and killed by a vehicle. They detained a childcare worker at a daycare in Chicago, as children watched. While immigrants bear the brunt of the policies, organizers and labor leaders insist that buying into the White House’s zero-sum narrative of native-born versus immigrants not only does the administration’s PR work for them but is empirically untrue. When one group of workers is terrorized or disappeared, worker leaders say, it threatens all workers’ ability to fight for their rights.

The scholarly research backs this up: Upticks in immigration enforcement are consistently associated with increased minimum wage violations for all workers and more dangerous workplaces. And contrary to the Trump administration’s claims, research shows that crackdowns do not create jobs for US-born workers but actually reduce them by removing people who make other jobs possible and by reducing local consumption. The armed federal agents descending on US communities are not targeting CEOs and business owners in Trump’s circles. They are going after day laborers, janitors, airport workers, and rideshare drivers, and the effects are felt throughout the working class.

“They are trying to divide different groups of our workforce, of the American workforce, against each other, so that they can treat one subgroup with a bit more favoritism,” Nammacher said. “By doing that, they can break the unity that we have to have to be able to actually get the raises and the health insurance and the retirement. Working people have never been able to win these things without being organized.”

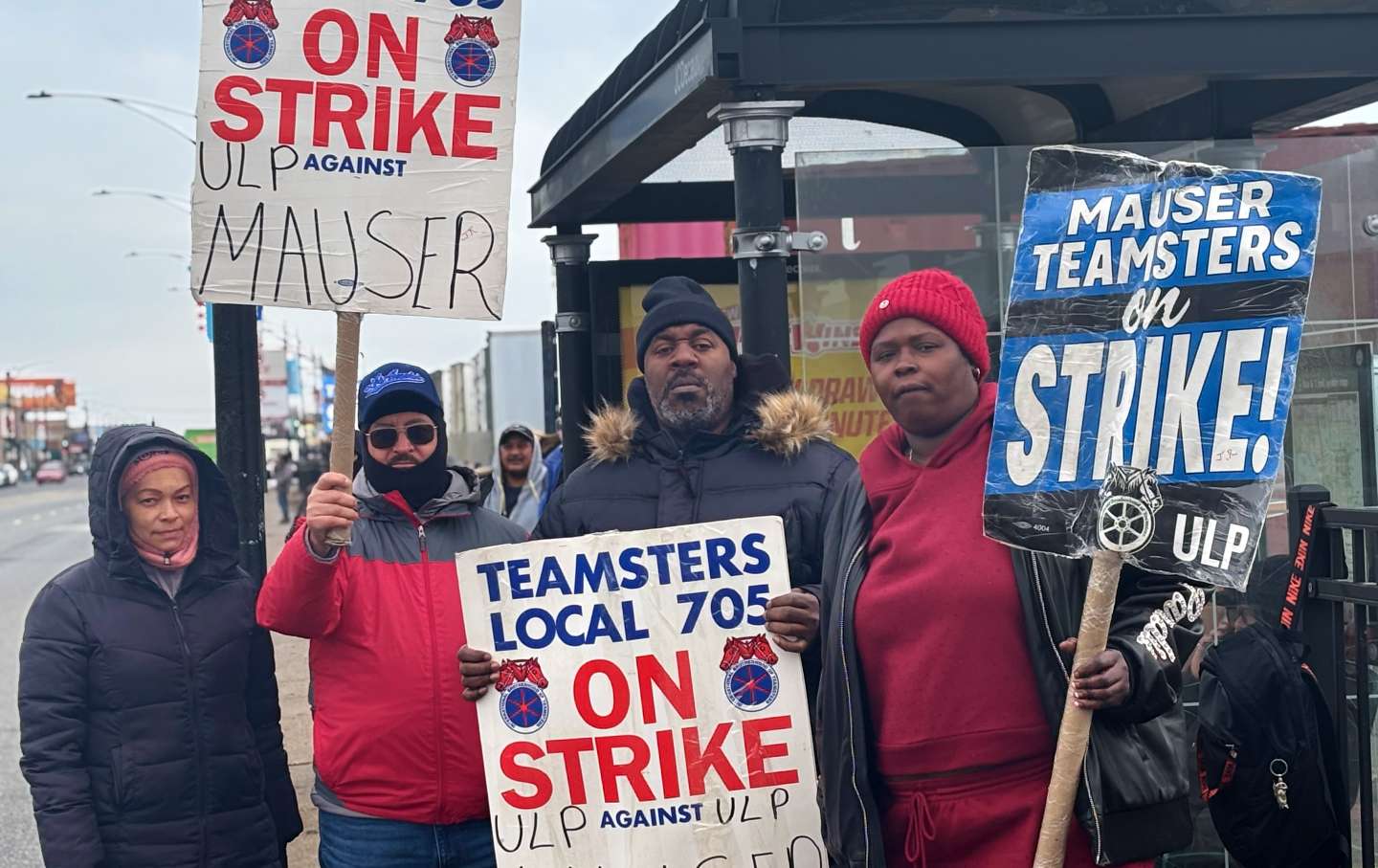

On the morning of December 16, striking Mauser worker Juanita Robinson was out on the picket line on Chicago’s Southwest Side when six vehicles pulled over. Armed federal agents, most of them wearing masks, got out, approached the strikers, and started asking workers for their identification. “It was scary when they pulled up on us, oh my gosh,” Robinson said.

By that point, the workers, members of Teamsters Local 705, had been on strike for six months. They had learned in September that the company, which reconditions large industrial drums, would be shuttering its Chicago facility for good. The workers were—and still are—holding out to demand a fair severance package. “They were messing with us,” Robinson said of the federal agents, a grim irony given that workers were striking, in part, over demands that the employer do more to protect immigrant workers. “We’re out there trying to make ends meet, and y’all abusing us.”

Trump’s high-profile border chief Gregory Bovino was there, along with other US Customs and Border Protection agents. The group “interrogated and laughed at our members while they were on the picket line,” according to a press statement from Teamsters Local 705. A few hours after the incident, Nicolas Carrizales Coronado, an attorney who is working as contract administrator counsel for the local, described the agents as harassing union members at a press conference. “Our members didn’t take the bait,” he said, “in large part” thanks to what they learned from a know-your-rights training they had previously received from Arise Chicago, a worker center.

While no union members were detained that day, the incident is notable because the international Teamsters union president Sean O’Brien told Senator Josh Hawley in January 2025 that “protecting illegal immigrants that come into our country to commit crimes and steal jobs, that’s a tough pill to swallow,” and has made political overtures to some MAGA leaders, like Hawley. (The international provided strike pay to the Mauser workers, as is typical for striking Teamsters.) Bovino claimed on social media that the interaction was friendly, but workers tell a different story. Robinson said she “absolutely” considers the act to be intimidation of striking workers, including workers like her, who grew up on the South Side of Chicago and are not immigrants. “They have no respect for nothing,” Robinson said, adding that she considers her immigrant coworkers “family.”

“They treated us like animals. And it’s not some immigrants who are affected—it’s everybody.”

There is data to suggest that increased immigration enforcement does, indeed, have a chilling effect on all workers. Much of what scholars know about the impacts comes from the study of Secure Communities, a program that boosted the sharing of information between local and state law enforcement and the Department of Homeland Security, with the goal of identifying and deporting undocumented people. Piloted by President George W. Bush and then dramatically expanded by President Barack Obama, Secure Communities resulted in the deportation of nearly half a million people from 2008 to 2014. Not only is Secure Communities one of the largest interior immigration crackdowns in US history; its scattered, county-by-county implementation over the course of four years allows researchers to conduct comparative analyses in a randomized fashion.

One academic paper published in June 2022 on the Social Science Research Network, an open-access research platform, showed how Secure Communities chilled worker advocacy. The agencies that enforce labor regulations, like the Wage and Hour Division and the Occupational Safety and Health Administration, are heavily reliant on worker complaints, since their inspection and enforcement capacities are limited by defunding. Yet workers who might want to complain face barriers, like fear of retaliation, so a drop in complaints could indicate that people are afraid to speak up.

“The question that I asked in the paper is, ‘How does immigration enforcement affect workers’ willingness to complain to these agencies, and in turn, what does that do to the working conditions that they face?’” said Matt Johnson, co-author of the paper, and associate professor in the Sanford School of Public Policy. The researchers found that Secure Communities resulted in “substantially reduced” complaints to OSHA in workplaces with Hispanic workers and an increase in workplace injuries. And it also resulted in increased minimum wage violations, both for Hispanic and non-Hispanic workers.

“I have individual data at the worker level on reported minimum wage violations,” Johnson said. “I find enormous effects for Hispanic workers—the onset of Secure Communities led to an over 100 percent increase in the prevalence of minimum wage violations for Hispanic workers. I also find large, but smaller effects for non-Hispanic workers—a roughly 40 percent increase in the prevalence of minimum wage violations.” Johnson calls this “clear evidence that the ‘chilling effect’ of immigration enforcement negatively affects labor market outcomes for all workers.”

When I asked Johnson to explain the cause of these trends, he said, “One important component here is that complaining to labor regulatory agencies is what’s called a public good. So if I complain to the Wage and Hour Division that I’m not getting paid minimum wage, and the enforcement agency comes and inspects my workplace, it might mean that my wages get restored. But it also might affect my coworkers, who maybe were also facing similar sorts of violations. So when one worker becomes more reluctant to complain, that might affect not only his or her conditions, but also those of his or her coworkers, and those in the rest of the labor market.”

Another study shows that a historical removal of immigrant workers from the US workforce didn’t help their American counterparts. A paper published in June 2018 in American Economic Review looks at the Kennedy administration’s deliberate exclusion of Mexican seasonal agricultural workers, known as braceros, starting in 1962. Under a series of agreements with Mexico, first established in 1942, the United States initially sought to increase the flow of Mexican seasonal workers to the United States, to work on temporary contracts in agricultural and war industries. When the Kennedy administration shifted course and called for exclusion instead, the main justification was that hiring braceros leads to the suppression of wages of US-born workers. About half a million braceros were excluded from the United States as a result; according to the paper, this was “one of the largest-ever policy experiments to improve the labor market for domestic workers in a targeted sector by reducing the size of the workforce.”

Yet, according to the paper, the “bracero exclusion failed to substantially raise wages or employment for domestic workers in the sector. Employers appear to have instead adjusted for foreign-worker exclusion by changing production techniques where that was possible, and changing production levels where it was not.”

This is not to say historians argue the bracero program of cheap labor was good for workers: It was used to suppress labor organizing and break strikes, and soon after it ended, the Delano Grape Strike began. But rather, the point is that the sudden, mass exclusion of an entire class of workers did not magically and immediately raise wages for US workers.

Ever since federal agents abducted six food service workers and members of UNITE HERE Local 17 from the Minneapolis–Saint Paul International Airport in late December, “a lot of workers have been very, very scared to come to work,” Feben Ghilagaber told me. She is a server for Minnesota Wild Bar and Restaurant, and her role as a steward for UNITE HERE Local 17 puts her in touch with people in Terminal 1, where federal agents maintain the heaviest presence.

When fewer people come to work, she explained, those who do show up “have to work short. We didn’t have enough employees. It’s very stressful for the workers, very stressful for even customers, because they’re not getting the service that they should get, because we are very stressed out working with short employees.”

Since mid-December, federal agents have been allowed to access areas of the airport that are beyond security clearance checkpoints, according to Geof Paquette, lead internal organizer for UNITE HERE Local 17—something he wishes the Metropolitan Airports Commission would more robustly oppose “to prevent people from getting kidnapped on the job.”

The presence of ICE creates a hostile and unpredictable work environment, Ghilagaber said. “It’s a very uncomfortable feeling. They’re walking around, they’re there for a purpose. Even for us who are citizens, they could take us and make life inconvenient until they investigate.”

“Knowing that your coworker is not there because they are scared to come to work, that they have children, they have to feed them, they have to pay rent, it’s just a very sad feeling,” she said.

David Siebert described this feeling as “a pit in your stomach.” He is a bartender for the Chili’s in Terminal 1, and he said that in late December, “I showed up to work and they had just just taken away a person from the food court, which is right by where my restaurant is that I bartend at. And I walk in just thinking it’s a normal day, and the servers are panicked, and it just creates this fear. When I heard it, my gut tightened up. It’s scary and wrong.”

“I do not have any risk of this happening to me,” he said. But the events have left him wondering, “What’s next?”

There is no evidence that wresting people away from their workplaces creates jobs for US-born workers, and if anything, data shows the opposite. In one study published in October 2023 in the Journal of Labor Economics, researchers used information from the American Community Survey, a dataset that looks at a randomized 1 percent sample of the US population, to examine employment levels in counties before and after Secure Communities was implemented. They found that the federal program led to a “significant decrease in the employment share” of people who are likely undocumented. However, researchers also found something else. There is “no evidence,” they determined, that Secure Communities improved the rate of employment for citizens. And, in fact, the program is estimated to have led to “a significant decline in citizen employment.” The removal of almost half a million undocumented workers from the job force didn’t increase jobs for US citizens—it reduced them.

Chloe East, an associate professor of economics at the University of Colorado Boulder, and the lead author of the study, explained over the phone that this trend can be attributed to a few factors. “The first is that immigrants and US-born people are actually complements in the labor market, rather than substitutes,” she said. “In order for the narrative, ‘When we remove one undocumented immigrant from the US, that creates one job opportunity for US-born workers,’ to be true, immigrants and US-born workers have to be willing to work in the same jobs. And that is clearly not true. Likely undocumented people are much more likely to work in lower-paying jobs that are also more dirty, more dangerous, have unpredictable schedules, jobs that are seasonal.”

“They’re not substitutes, but actually, they’re complements,” she explained. “When you think about the owner of a restaurant, in order for that owner to hire waiters and waitresses and hosts and hostesses, which are jobs typically taken by US-born people, they also have to be able to hire cooks and dishwashers, and these jobs are much more often taken by immigrants. And so when all of a sudden that restaurant owner can’t find anybody to do the dishwashing, they may have to reduce their hiring overall because of this shortage in the particular occupations that immigrants take.”

There is another factor that East and the other researchers identified: the impacts on demand in a more general sense. “When many people are all of a sudden removed from a local area because of detention or deportation, or afraid to leave their homes to get haircuts and eat at restaurants, that reduces consumer demand overall and reduces economic growth and reduces new job opportunities for everybody, including US-born workers,” East explained.

Other papers have found that undocumented workers don’t take American jobs. In fact, the effect on jobs for US-born workers ranges from zero to positive. There is even evidence that immigration crackdowns lead to a drop in homebuilding and a rise in construction prices.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →It is difficult to know where the current immigration crackdown is headed, but the Trump administration has the resources to carry it out for a long time. Thanks to an increase that went into effect October 1, 2025, the administration has $170 billion in new funding for immigration enforcement. This amount is unprecedented. If the US immigration enforcement apparatus were an army, it would be the 13th most funded in the world, just below Israel’s military, and above Canada’s, as Lindsay Koshgarian and I reported for In These Times.

Jimmy Williams Jr., the general president of the International Union of Painters and Allied Trades (IUPAT), told me that Trump’s immigration crackdown is not going to deliver better jobs for American workers. “I can really only speak on behalf of construction,” he said. “The way the low-road, unorganized construction sector works is, workers are often misclassified as independent contractors. Most immigrant workers that come to this country migrate to service jobs, construction jobs, and that model is ripe for abuse. And it’s not just abusing immigrant workers.”

“When workers don’t have the ability to speak out and have the ability to make claims against their employers for misclassifying them or stealing wages, then nobody speaks out, and there’s no enforcement, and it just drives wages further down.”

Every labor leader I talked to for this story emphasized that, despite the difficulty, workers continue to band together. “Even in this hard moment, there’s still workers standing up and doing something about the circumstances,” said Laura Garza, the executive director of Arise Chicago. “People are still being brave,”

But conditions are worsening. According to Williams, intimidation has always been a problem, but IUPAT organizers who reach out to nonunion construction workers report that it’s growing more pronounced. “It’s harder and harder to get workers to come forward because of the fear,” Williams said.

“It drives down your collective power to be able to bargain for more.”

More from The Nation

How Brothel Workers in Nevada Just Made Labor History How Brothel Workers in Nevada Just Made Labor History

The courtesans at Sheri’s Ranch were staring down a horrifying new contract. So they did what workers everywhere do: They got organized.

Democrats Must Listen to Workers Democrats Must Listen to Workers

How winning people’s trust involves listening to their challenges, ambition, ideas, and stories.

Zohran Mamdani Is Putting Corporate Sick-Leave Cheats on Notice Zohran Mamdani Is Putting Corporate Sick-Leave Cheats on Notice

The mayor announced that the Department of Consumer and Worker Protection will investigate employers where more than half their workers take no paid time off in a given year.

The Ghosts of Colonialism Haunt Our Batteries The Ghosts of Colonialism Haunt Our Batteries

With its cobalt and lithium mines, Congo is powering an energy revolution. It contains both the worst horrors of modern metal extraction—and the seeds of a more moral economics.

The Trump Administration Wants to Make It Easier Than Ever to Exploit Farmworkers The Trump Administration Wants to Make It Easier Than Ever to Exploit Farmworkers

What is being described as “reform” in Washington will only make the abuse and wage theft that plague the program even worse.

Is Union Power Growing in Mamdani’s New York? Is Union Power Growing in Mamdani’s New York?

Following the Mamdani administration’s talks with the CUNY faculty union, three professors have returned to class after losing their jobs for their pro-Palestine activism.