Can We Blame Private Equity for Everything?

Did PE firms make the world worse? Or was it something else?

The Blackstone Group offices in New York, 2013.

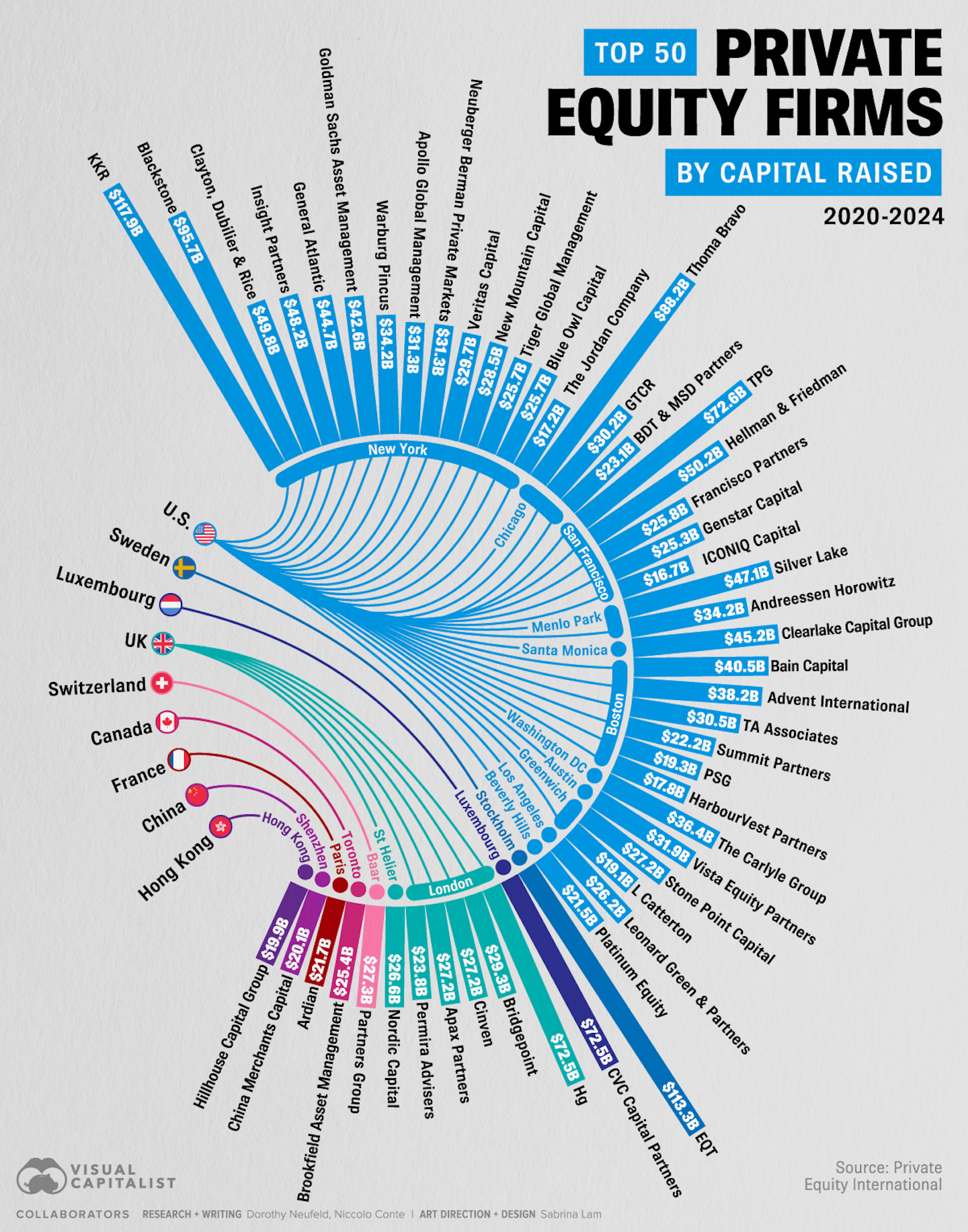

(Scott Eells / Bloomberg via Getty Images)The 2010s were, among other things, the decade of private equity. A segment of the finance sector long shrouded in myth and controversy, private equity is at its core a straightforward business: A firm raises money from clients (such as pension funds) and uses it to buy businesses and other assets (such as real estate), usually adding a large chunk of borrowed money to the mix. The PE firm aims to increase the value of the acquired assets and then sell them at a profit. Clients receive whatever is left of any gains after the deduction of fees, which include a share of those gains. The “equity” in private equity refers to the ownership stakes the PE firm takes, while the “private” means these investments are held outside of public stock markets.

Books in review

Bad Company: Private Equity and the Death of the American Dream

Buy this bookThough private equity has been around since the 1970s, its growth went into overdrive after the global financial crisis of 2007–09. Until that point, banks—especially investment banks like Goldman Sachs and JPMorgan—had been the most powerful players in the world of global finance. Yet banks were widely held responsible for the crisis, leading regulators in the United States and a host of other countries to clip their wings. As big banks became “more heavily regulated and scrutinized,” Bloomberg Businessweek reported in 2019, private-equity firms like Apollo, Blackstone, and KKR moved decisively out of their shadow. “Almost everything that’s happened since 2008 has tilted in [private equity’s] favor. Low interest rates to finance deals? Check. A friendly political climate? Check. A long line of clients? Check…. Private equity managers,” the Bloomberg Businessweek report concluded, “won the financial crisis.” By 2021, the average Blackstone employee was earning more than $2 million per annum, and the firm’s CEO, Stephen Schwarzman, had a net worth of nearly $40 billion.

It is thus little wonder that recent years have seen a slew of books aimed at coming to grips with the PE phenomenon, with more in the works. The latest addition to the crop is Bad Company: Private Equity and the Death of the American Dream, by the journalist Megan Greenwell. Although there have been notable exceptions—including two memoirs about working in private equity, from very different perspectives—most of the recent books, as Greenwell points out, have been attempts to understand and evaluate PE in broad terms as an economic and social phenomenon: what it is, how it operates, its size and structure, and so forth. Such books focus, Greenwell observes, “on the macro level: the number of companies that shutter, the number of jobs that disappear, the number of dollars that are won and lost.”

In Bad Company, Greenwell takes a different tack, shifting the lens from the macro to the micro level. “When we talk about how private equity affects communities,” she writes, “we’re really talking about how it affects people, the individuals who have no choice but to rely on firms for their jobs, their homes, their essential services.” And so she presents us with the stories of four individuals whose lives have been impacted by the PE takeover of, respectively, a retail chain, a small-town hospital, a newspaper company, and an apartment complex. Through these profiles, Greenwell paints a picture of a decidedly unedifying phenomenon: of PE firms swooping into local communities, buying local assets, and radically degrading the conditions of people’s lives. But does this analytical shift from the macro to the micro scale ultimately pay dividends for our understanding of the nature and effects of the PE business?

There are, of course, always different ways to tell a story, and the story of private equity is no different in this respect. However, when the mode of analysis is the exploration of individual lives, as it is in Bad Company, it’s important to think closely about what those lives can and cannot meaningfully tell us about the wider phenomenon under consideration.

When books that explore broad social phenomena through individuals’ life stories work particularly well, there is usually an intimate and necessary connection between the lives in question and the phenomenon to which the author is relating them. The sociologist Matthew Desmond’s 2016 book Evicted is a good example. In it, Desmond follows eight individuals in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, as they and their households go through the process of eviction at the hands of their landlords. Focused on these individual lives, Evicted also manages to serve as an exemplary study of the wider phenomenon of eviction because of two key characteristics of the latter. The first is that eviction is precisely something that happens to individuals. The second is that, for tenants, involuntary eviction is a unique hardship: While housing insecurity can take many forms and can be suffered in all sorts of ways, nothing else matches the experience of being evicted from one’s home against one’s wishes.

Then what about working for a company or living in an apartment that is taken over by a PE firm? Is that, too, a unique type of experience? Consider Greenwell’s four profiles: Liz is laid off without severance from Toys “R” Us when its PE owners close its last 200 stores; Roger, a doctor, sees his beloved hospital in rural Wyoming stripped of resources and crucial services after a PE takeover; Natalia is a reporter at a local newspaper whose staff is slashed after PE ownership takes hold, diminishing the paper’s capacity to report and hence the community’s access to local news; and Loren moves from public rental housing into a PE-owned apartment complex where mold and infestations of mice and roaches are not allowed to stand in the way of rent hikes. Is there a necessary and intimate connection between these types of personal experience and the phenomenon of private equity, one that makes them “PE experiences” per se?

Greenwell maintains that there is indeed such a necessary and intimate connection. For her, the experience of working at a PE-owned business or living in PE-owned housing is special inasmuch as the PE ownership and operation of such assets is itself special. As she sees it, it all comes down to profitability—that is, what ostensibly connects the individuals whose lives Greenwell chronicles, thus making theirs a shared experience as opposed to four unrelated ordeals, is their subjection to a distinctive profit calculus. But is that calculus unique to PE?

Early in Bad Company, Greenwell cites the American economist Milton Friedman and his influential 1970 essay about the role of the corporation in American capitalism. “The social responsibility of business,” Friedman famously insisted, “is to increase its profits.” And that, he added, is its sole responsibility. Friedman’s injunction has been endlessly debated in the decades since. For Greenwell, its particular relevance is that private equity, and only private equity, has, in her view, followed the Friedmanite philosophy to the letter. Friedman, she says, “set the stage for the rise of private equity.”

To explain how PE differs from other forms of owning and operating assets like businesses and real estate, Greenwell offers the following take: “The definition of success is loftier in the private equity world: not just making profits, but maximizing them.” “Merely making a profit was no longer enough,” she writes, for instance, of what changed when Apollo Global Management took over LifePoint Health and its chain of rural hospitals across the US, including Roger’s hospital in Wyoming. “Now the goal,” à la Friedman, “was to maximize shareholder value.”

In positing this Manichaean distinction between “normal” capitalist businesses that “just make” profits and PE firms that seek to “maximize” them, Greenwell establishes a pro forma narrative of what happens when private equity comes to town: “When the only worth of a local grocery store, a newspaper, or a hospital is the short-term profits it can generate, the company becomes little more than a mine awaiting extraction.” Which, crucially, is not what that company had previously been: “Businesses that were once pillars of a society founder and crumble,” Greenwell writes. By this way of thinking, other capitalist businesses, unlike PE firms, do take seriously “responsibilities” other than profit-making.

Far be it from me to downplay private equity’s profiteering, but this argument clearly rests on a questionable supposition: Is it genuinely credible to cast non-PE firms as less obsessed with profit? Try telling BlackRock, State Street, or the other major shareholders in America’s 4,000-odd public companies that the goal of those companies is something besides maximizing shareholder value.

Greenwell’s own reporting demonstrably belies the distinction her book posits. Take Gannett, the media group that owned the local newspaper employing Natalia when it was acquired by Fortress Investment Group in 2019. Was Gannett formerly a pillar of local society, whose modus operandi was rudely upended by the PE barbarians? Hardly. “Well before private equity was in the local media game,” Greenwell informs us, “Gannett was creating [PE] firms’ playbooks for them: ruthlessly consolidate, centralize as much as possible, boost shareholder value at all costs—even when the cost was the journalism, the company’s ostensible raison d’être.” Gannett, it turns out, was already an archetype of Friedmanite capitalism, red in tooth and claw.

The same kind of contradiction befalls the other case studies here. The more Greenwell tells us about the businesses that private equity came in and subsumed, the less like pillars of society and paragons of business ethics they appear to be. Rather than substantiating her thesis of a sui generis role for private equity in destroying civil society and the American dream, what Greenwell actually reaffirms is a kind of bog-standard point about how business is done in America. Because, of course, it wasn’t just private equity that took Friedman’s gospel to heart. Capital at large did.

None of this is to say that there aren’t important differences between PE firms and other owners and managers of businesses and real estate—that things do not change when PE comes to town. Very often they do. Nor is it to say that the individual stories that Greenwell spotlights in Bad Company have nothing to tell us about the corrosive effects of a corporate and financial world single-mindedly beholden to maximizing shareholder value. But as insights, in and of themselves, into the nature of the PE phenomenon? Not so much.

In reality, much the same book, containing much the same litany of woes, could be written about the effects on individuals and communities of adventures in the capitalist profit imperative that have nothing to do with private equity whatsoever. Indeed, over the years, many such books already have been written, from Michael Harrington’s The Other America to Barbara Ehrenreich’s Nickel and Dimed and Jefferson Cowie’s Stayin’ Alive. Does a private-equity takeover often result in dire outcomes for workers and tenants? To be sure. But it is far from being unique in that.

It’s for good reason that the other recent books seeking to comprehend and appraise the PE phenomenon are primarily pitched at the macro level. Private equity is a quintessentially macro-scale enterprise; instructive analysis of it cannot eschew that analytical scale. Boiled down to its essence, private equity is an investment phenomenon. Yet if investment is the term we use to refer to the myriad ways in which actors holding surplus capital are connected to the actors who put that capital to work, then private equity represents above all a distinctive way of configuring that connectivity. Arguably, its cardinal characteristic—evident to all institutional stakeholders—is that the investment explicitly does not have an open time horizon. Allocating client capital via funds with fixed lifespans, and returning the capital (ideally with a profit) to clients upon the funds’ termination, PE managers buy assets—and this cannot be emphasized enough—in order to later sell them. Whether the acquired businesses or rental homes or whatever else it may be are held for one year, three, or five, everything that the PE manager does with those assets while they are under its control is done with a view specifically to maximize the price at exit. If there is a single thing that one must grasp in order to understand private equity, this is it.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →Bad Company, to be clear, does not eschew macro-scale analysis altogether. Greenwell has plenty to say about the role of debt financing in PE buyouts; the relationship of PE firms to their clients in the institutional-investor community; the significance of PE tax breaks, which generations of policymakers have refused to abolish; and much else besides.

Ultimately, it’s a question of balance. The examination of how a handful of individuals experience life at the sharp end of private equity’s pillaging can, without doubt, add texture and color to our understanding, helping to humanize the impacts of an industry often discussed in dry financial terms. But it’s questionable whether it can do more than that, not least because those experiences are not categorically different from the experiences of individuals ensnared by capitalist ravages more generally.

Private equity, to my mind at least, has always internalized a fundamental tension concerning its ability to exit its investments, which is typically achieved either through a sale to another private buyer (whether a strategic trade buyer or another financial investor) or through an IPO on the stock market. Why, one wonders, are other investors willing to pay the top-dollar exit price that private equity, by its very nature, demands? If—as is generally assumed to be the case—the PE firm has itself exhausted all the obvious opportunities for value enhancement and extraction during its period of ownership, why buy what’s left? If all the fruit has been plucked and the PE firm has achieved its signature goal of exiting at maximum value, is not the only way for the subsequent value of those assets, in fact, down?

Over the past couple of years, it seems that the penny may have finally dropped. PE firms are widely struggling to exit their investments profitably and return cash to their clients. In mounting desperation, they have turned to launching so-called “continuation vehicles”—essentially, mechanisms for extending fund life and protecting the book value of marginal assets—but clients, smelling a rat, have been reluctant to back them. A vicious circle seems to be setting in: Required to hold on to assets for longer and longer periods, private equity is, as the financial journalist Katie Martin observes, “squeezing more of the juice out of them, and leaving little for public market investors,” thereby making it even harder still to achieve an exit.

The upshot is that the PE sector is now sitting on some $3 trillion worth of unsellable assets. And as clients have become increasingly frustrated with the difficulties of achieving and realizing gains from PE investments, they have responded by beginning to allocate less capital to the sector. Private-equity fundraising slid to a seven-year low in the last year, and with a record number of firms chasing this dwindling pot of capital, many have resorted to “unprecedented enticements to attract new investor cash,” not least markedly lower fees. No wonder that PE firms have meanwhile been lobbying furiously for access to new sources of capital, with America’s individual retirement savings—hitherto off-limits for PE managers—considered the holy grail, and President Trump seemingly willing to oblige.

In short, the PE sector, and its profitability prospects, are under pressure as perhaps never before, making it possible to ask a question that until recently would have been deemed outlandish: Has private equity had its moment in the sun? If so, and for reasons that Bad Company and all the other recent PE books make abundantly clear, few will feel any sympathy.

More from The Nation

Has Contemporary Fiction Ignored the Working Class? Has Contemporary Fiction Ignored the Working Class?

Claire Baglin’s bracing On the Clock gives its readers a close look at work behind the fry station, and in the process asks what experiences are missing from mainstream letters.

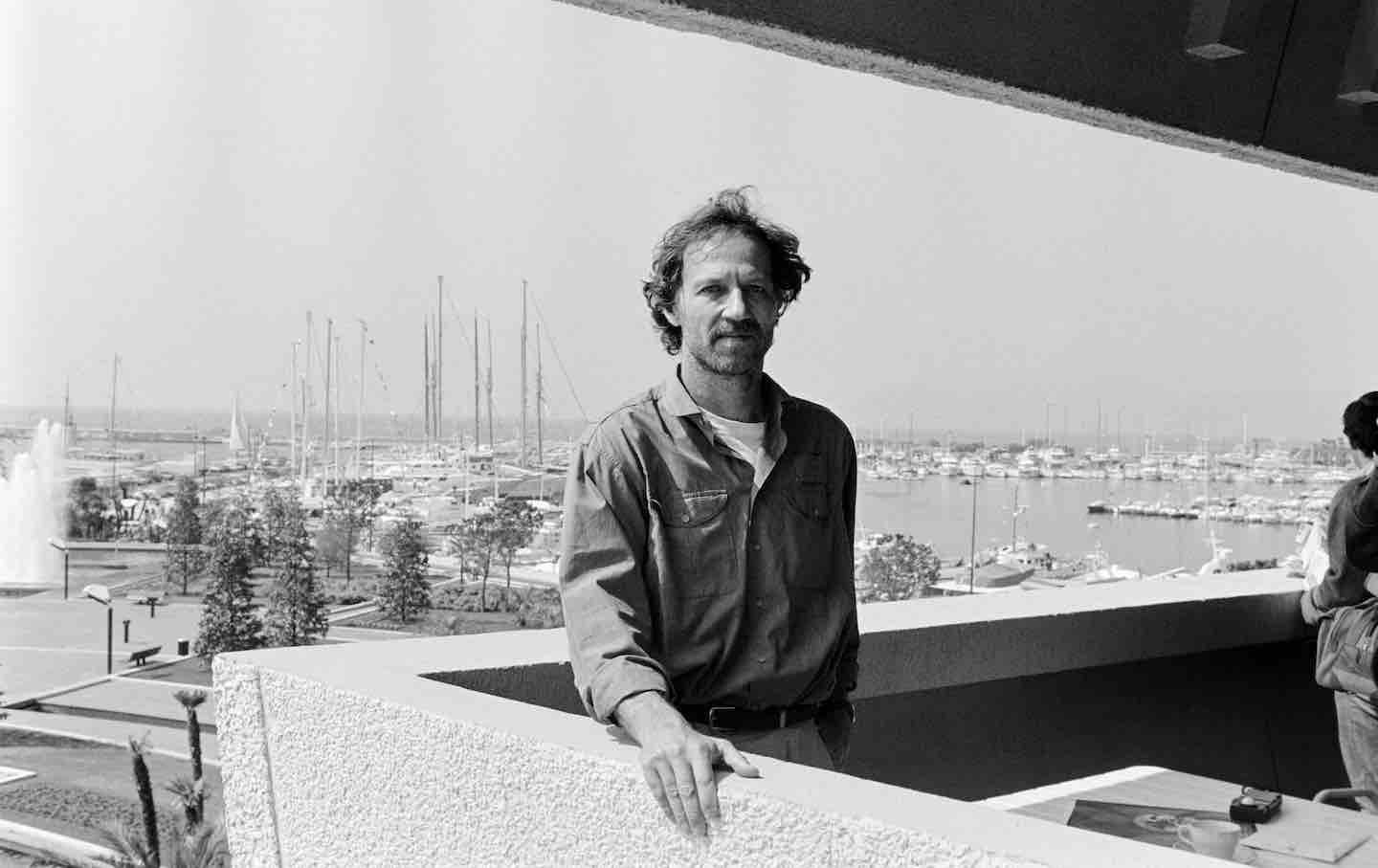

Werner Herzog Between Fact and Fiction Werner Herzog Between Fact and Fiction

The German auteur’s recent book presents a strange, idiosyncratic vision of the concept of “truth,” one that defines how he sees the world and his art.

Do Humans Really Understand the World’s Disorderly Rivers? Do Humans Really Understand the World’s Disorderly Rivers?

In James C. Scott’s last book, In Praise of Floods, he questions the limits of human hegemony and our misplaced sense that we have any control over the Earth’s depleted watershed....

The Scramble for Lithium The Scramble for Lithium

Thea Riofrancos’s Extraction tells the story of how a critical mineral became the focus of a worldwide battle over the future of green energy and, by extension, capitalism.

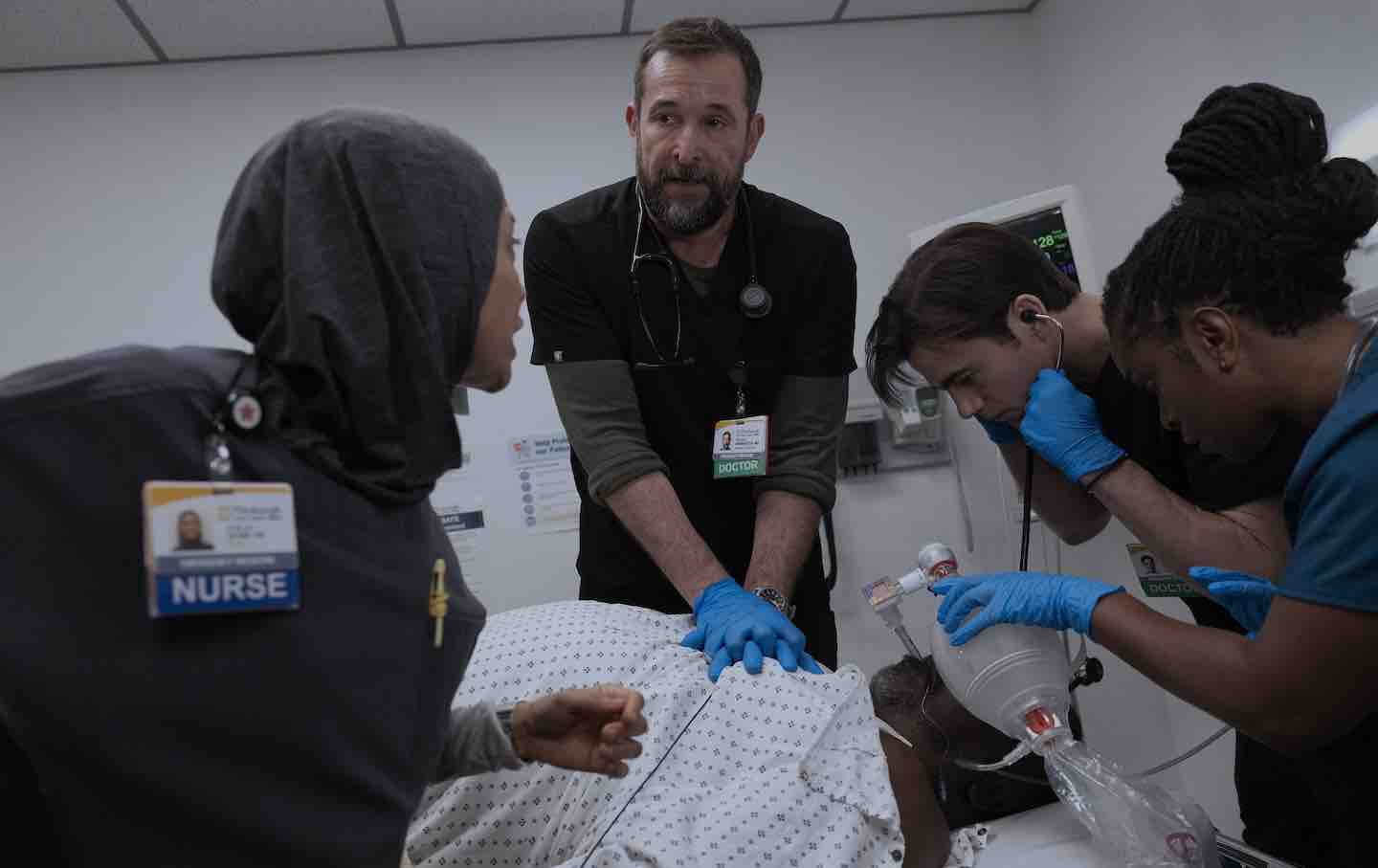

“The Pitt” Shows Doctoring Uncensored “The Pitt” Shows Doctoring Uncensored

The second season tackles everything from the role of AI in medicine to Medicaid cuts. But above all, it is about burnout.