The World’s Problems Explained in One Issue: Electricity

Brett Christophers’s account of the market-induced failure to transition to renewables is his latest entry in a series of books demystifying a multi-pronged global crisis.

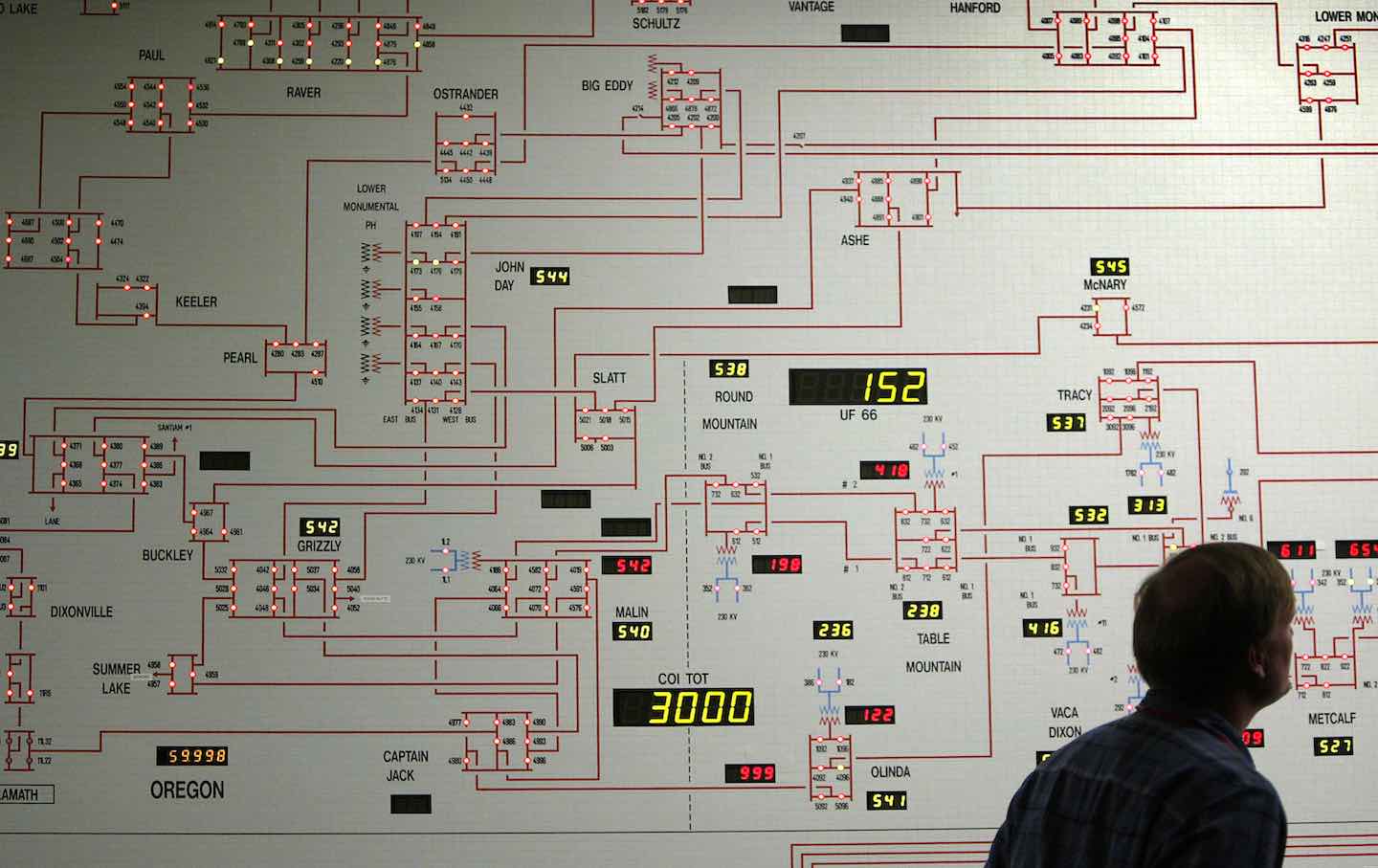

A figure looks at the dynamic map board showing power distribution through California’s electrical grids in the control center of the California Independent System Operator, 2004.

(Photo by David McNew / Getty Images)

The idea that markets are the best way to solve social problems or distribute scarce resources must be one of the most thoroughly exploded propositions in the history of social thought. Proponents of this notion have accumulated quite a list of qualifiers and exceptions: asymmetric information, market failures, natural monopolies, externalities, imperfect competition, irrationality, public goods, time inconsistency, and principal-agent problems, just to name a few. The empirical record is even worse. We are now more than 40 years into a global process of generating more markets in more things, including healthcare, childcare, education, housing, energy, and retirement. The results are unambiguous: The great expansion of the marketplace, and the long process of privatization and liberalization needed to achieve it, has led to a world that is more expensive, more unequal, and not appreciably more efficient. In his new book, The Price Is Wrong, Brett Christophers finds yet another and potentially cataclysmic example of the failures of the marketplace: the production of electricity.

Books in review

The Price Is Wrong: Why Capitalism Won’t Save the Planet

Buy this bookThe Price Is Wrong opens with a clear puzzle: Despite a popular consensus that “the economic key to renewables winning out is being cheaper than fossil-fuel-based electricity,” the transition from fossil fuels has not happened, even though renewables—mainly in the form of wind and solar power—are now more cost-effective. In fact, because electricity consumption continues to rise faster than the amount supplied by renewables, the gap to be filled is getting larger and larger, and the renewables transition is falling further and further behind. And the stakes only keep getting higher. Electricity is not just the largest source of greenhouse gas emissions, but policymakers around the world have decided that the best way to decarbonize the economy is to make as many things as possible electric—which, as Christophers points out, is unfathomably counterproductive if the electricity grid itself still runs on fossil fuels. For that reason, the failure to switch to renewables is not only a puzzle but a growing disaster, undermining other efforts to decarbonize economic and social life. If electricity can finally be produced more cheaply with renewables than with fossil fuels, why has the market not led the transition?

The answer, as usual, is profit—more specifically, expected profits. As Christophers painstakingly demonstrates, electricity generation, especially from renewables, is highly competitive, which drives down profits. A renewables generator that “earns out” its construction costs in under 10 years is considered a success. At a basic level, selling its output more cheaply means that it takes longer to repay its investors. The investors are overwhelmingly financial institutions, which fund renewable-energy projects through debt, so the terms of debt and the projected profits of finance tend to be the ultimate failure point. And there are further problems: Renewables are prone to boom dynamics, which can drive profits to zero and even lead to “curtailment,” or the enforced reduction of supply because sufficient demand does not exist. Prices can be extremely volatile, in both the short and the long run. For all of these reasons, investment in renewable energy is often not profitable for private investors, so even if the electricity can be delivered cheaply, private markets do not choose to do so. As Christophers puts it, “electricity essentially was and is not a suitable object for marketisation and profit generation in the first place.”

If not the market, then the state is the only viable alternative. Christophers shows the many ways that states are already deeply involved in the creation and transmission of electricity, both in the physical sense and in the regulatory and market-creation sense. But he is skeptical of the ability for states to de-risk, subsidize, or nudge private markets into action. Instead, he concludes that direct public ownership of electricity production is the only feasible way to meet the scale, speed, and administrative complexity of the necessary transition from fossil fuels to renewable energy. The Price Is Wrong sets out the rationale for state ownership by systematically demolishing the conventional wisdom that prices drive markets and that markets will solve social problems. There are some hopeful signs, especially at the local level, that state ownership is back on the agenda—but, as ever, the politics of what is feasible lags well behind both reason and necessity.

Over the past eight years, Christophers has produced five remarkable books of critical political-economy scholarship. First, in The Great Leveler: Capitalism and Competition in the Court of Law (2016), he argued that antitrust and intellectual property law alternate in salience, either restoring corporate profits after crises, or restoring competition after periods of monopoly and rent-seeking. In other words, he showed how the law ensures that capitalism is never so competitive as to drive down profits nor so permanently monopolistic as to produce stagnation. Then, in The New Enclosure: The Appropriation of Public Land in Neoliberal Britain (2018), he traced the privatization of about 10 percent of the British landmass since 1979. Contrary to most public discussion, the largest transfer of public assets to private ownership in Britain was not in banks or housing but land itself, and the subject was barely studied, let alone debated or contested. Christophers used the transfer of public land in particular as a way to consider the logic of privatization in general, and found that it delivered none of the promised benefits and many very predictable problems like elite wealth-hoarding and social dislocation. Given the recurrent proposals to privatize the Amazon rain forest or US federal land, his point was to show that enormous and destructive transformations of economic and social life can happen without anyone particularly noticing.

In 2020, Christophers followed with Rentier Capitalism: Who Owns the Economy and Who Pays for It?, which showed how ownership of a few key types of assets—land, intellectual property, natural resources, and digital platforms—is concentrated among a small set of incredibly wealthy corporations and individuals whose power and accumulation derives from their passive receipt of rent. He proceeded to investigate that small group even further; the result, Our Lives in Their Portfolios: Why Asset Managers Own the World (2023), is a terrifying book. It traces the emergence of private equity and other kinds of asset managers since the 1990s and finds that they now own nearly everything, from roads to houses, hospitals, farmland, and the infrastructure that delivers water and electricity.

In Oakland, California, for example, the number of homeless people has doubled since 2015, but there are four empty housing units for every homeless person. Many of these are owned by closed-end real estate investment trusts that have no interest in rental income or dealing with tenants and maintenance: They keep these properties off the market for a period of years, benefiting from the rise in prices, and then sell them and distribute the profits to their shareholders. In this way, Christophers is able to show how half a million retired schoolteachers in Pennsylvania came to own a share of thousands of rental apartments formerly owned by the East German state, and how the Australian asset management firm Macquarie came to own the vast majority of the municipal and regional sewers across England.

Monopoly and intellectual property, land privatization, rentier economies, asset managers, private equity, and now climate change—if you want to read only one person to understand the broken and unequal world around us, you need to read Brett Christophers. Each of his books is thoroughly researched and intensely detailed, but also clear and readable, studded with memorable examples. With The Price Is Wrong, Christophers extends his critique of privatization and marketization and adds another facet to his work on the concentrated private ownership of infrastructure, but now he turns to the urgent crisis that will spell catastrophe for us all: a warming world.

The first two-thirds of The Price Is Wrong unpacks the architecture of electricity markets, from funding to generation to transmission, and how individual components like vertically integrated electricity boards or intermediary electricity retailers have been privatized or monopolized or unbundled (meaning split from one integrated system into many) at different moments. Thinking of electricity as a single thing is a mistake: The incentives and interests of consumers, transmitters, and generators can all be mutually conflicting. And fixation on the retail or wholesale price of electricity is the fundamental mistake: Prices are volatile, so there are different ways to measure them, each with its own limitations. Prices also constitute more than one thing, because a cost to one party is revenue to another. Buyers of electricity want a low price, while for sellers, low prices undercut their profitability. Instead of obsessing over price, Christophers illustrates that profits—especially anticipated profits—are the most important driving factor in renewables adoption, because the decision whether to fund or not to fund a project, and whether to build a renewables or a fossil-fuel plant, is first and foremost a decision about expected profits. The structure of electricity markets has not produced an environment in which renewables have systematically and reliably higher expected profits than fossil fuels, so there has been no large-scale transition to renewable energy, regardless of the final price.

The last third of The Price Is Wrong traces the various failed attempts by governments to address the symptoms of this problem while studiously not acknowledging the disease. In a cosmically terrible bit of bad timing, policy concerns over fossil fuels and climate change emerged in the 1990s, when policymakers considered markets to be the only conceivable solution to social problems, and prices as the key variable for producing functioning markets. In this way, decades of commitment to market solutions have created unwieldy institutional structures and a thicket of state interventions instead of direct state control, and those results, in turn, have made structural change more difficult to accomplish. Across his many examples, Christophers reveals over and over the ways that some clever subsidy or market regulation produced perverse new incentives or temporarily obscured more fundamental structural failures. To take one example, developers of renewable-energy generation often sign long-term price agreements with large institutional buyers of electricity like Amazon or Facebook (which are keen to claim that they are among the world’s biggest buyers of renewable electricity). Such agreements mitigate risk on both sides, because buyers and sellers know the price of electricity in the long term—but if the price of financing or equipment changes before a renewables plant is built, it may abruptly become potentially unprofitable and never actually get built. Existing plants may find that they cannot deliver electricity at the agreed rate while remaining profitable, so governments may provide subsidies that kick in below certain prices—a kind of insurance that sometimes allows renewables to appear to be “zero subsidy” even when they are not. “There is ample evidence,” Christophers concludes, “of various props, rules, regulations, and norms being required to render electricity buyable and sellable at a profit—that is, to tame the unruliness and render it commodity-like—and to sustain the fiction that all of this somehow represents ‘real’ profit in a ‘real’ market. Yet plainly it does not represent such.”

Christophers always displays an in-depth knowledge of his subject. He knows the average construction cost per kilowatt-hour of US onshore wind farms. He knows the day-ahead wholesale electricity price in Germany. He knows how merit-order pricing structures stack wholesale bidders, and what that means for the supply throughput of different types of generators. All of his books have a similar approach: a clearly stated and powerful argument followed by a pile of minute factual detail. The clarity of the arguments is a great relief. These are not books about how “technopolitics” “reifies and (re)inscribes” “epistemic residuality” into “the Capitalocene”; instead, Christophers is doing instigative left theorizing while liberating himself and the reader from academic jargon.

The intense facticity of his research has a persuasive effect. After all, anyone who knows this much about the management of Norwegian wind farms or the asset structure of a real estate investment trust is probably right about their argument. Christophers is also compelling in his delivery, and the individual chapters or passages can be fascinating, much in the way that watching a documentary about how guitars are built can be unexpectedly fascinating. The compression and clarity mean that each of his books is an essential research tool for anyone interested in their subject, though I also think the thick evidentiary presentation limits his readership. This is unfortunate, because Christophers is persuasive that the details matter: If transmission were not separate from generation, if pricing were determined differently, if financing were on different terms, the problem would be different. This is a terrific way of fracturing an overwhelming structural problem into a series of thinkable, actionable, contingent little problems. Solving climate change all at once is not just a problem of titanic scale; it is nearly impossible to fathom. But something like solving the correct level of subsidies for credit de-risking seems very doable.

But that point returns us to a familiar and depressing place. The Price Is Wrong is not really a book about evil, rapacious, world-consuming capitalists; it is a book about the ways that “a profit- and market-centered model is inappropriate to the relatively simple proposition of delivering a single fictitious commodity,” let alone the considerably more difficult proposition “of transforming—quickly, seamlessly, and comprehensively—a whole complex system of social and economic life.” The core causal problem is decades of elite consensus around the idea that markets are the best ways to solve social problems. So how do you change decades of conventional wisdom—especially conventional wisdom buttressed by material interests, ideology, and the forbidding edifice of economic rationality?

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →Across his five books, Christophers has broken many of these problems down, shown how they work from the inside, and rendered them intelligible to outsiders. Together, these books constitute an agenda for a radical, confrontational politics, ready just as soon as any kind of organized political formation arrives. In that sense, they also make for profoundly gloomy reading. Christophers has shown that a set of bad ideas about markets has produced a concentration of wealth and power on a global scale that has stripped control of the necessary components of everyday life from any sort of democratic control. The perpetuation of this condition, crucially, is not due to an absence of alternative ideas. Christophers is not here to tell us how to make the politics that will remake the world; instead, he issues a warning. Our current crises will not solve themselves, because they are the result of the entrenched power of capital and the demands of profitability. The solution is a matter of moving away from private profitability to democratic state control, but that leaves the problem of how we can imagine it being achieved, since the state as it currently exists is the servant of capital.

Christophers wraps up The Price Is Wrong with the example of the Build Public Renewables Act, which was passed in New York State in 2023, and which requires the New York Power Authority to build and operate renewable-energy generation when the private market fails. He takes this as a hopeful sign of potential change. Time will tell whether it signals a wider transition, he concludes, and he’s right. But there isn’t much time left.