Pacita Abad Wove the Women of the World Together

Her art integrated painting, quilting, and the assemblage of Indigenous practices from around the globe to forge solidarity.

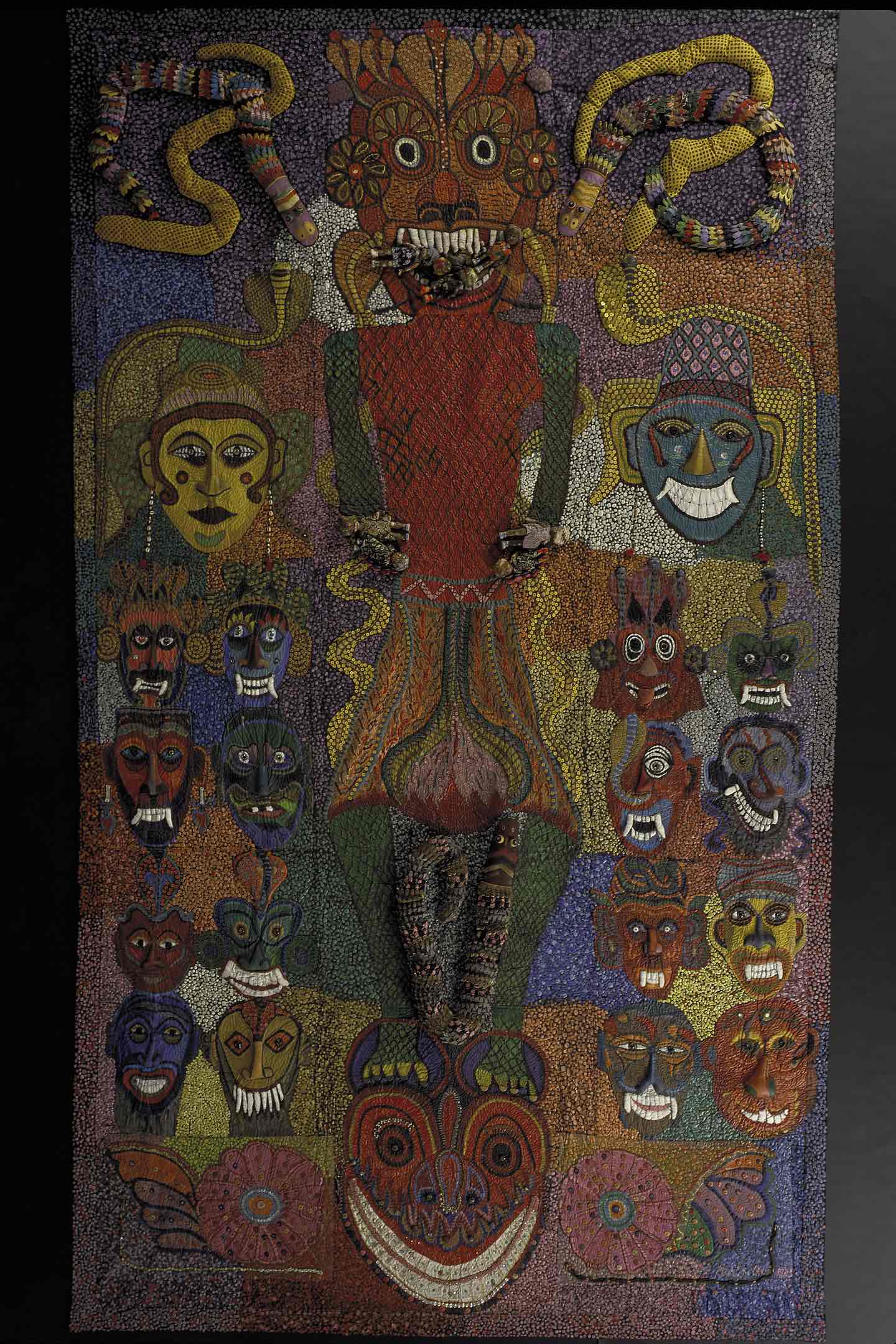

At the end of the Pacita Abad retrospective at the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis last summer, there hung, unassumingly, her most monumental work: a 17-foot-high trapunto painting titled Marcos and His Cronies (1985). Trapunto, a style of quilting with medieval Italian origins that Abad first learned about from the feminist artist Barbara Newman, is integral to her practice; it involves painting and collaging on canvas, adding cloth backing, and then stuffing filling in between the layers. When the two layers are sewn together, the final product is a soft, textured work unconstrained by the flatness of a stretched frame.

Marcos and His Cronies is the largest instance of Abad’s trapunto painting, and it employs the signature hallmarks of her style: tribal artistic motifs, profuse embellishments, and florid color. Elected as president of the Philippines in 1965, Ferdinand Marcos declared martial law in 1972, inaugurating a 14-year dictatorship in the country. His reign was marked by rampant corruption and the arbitrary apprehension, detention, and execution of those suspected of challenging his rule. Among Abad’s works, Marcos and His Cronies stands out as uniquely confrontational in its political message.

Abad depicts Marcos as a dragon demon, inspired by the exaggerated features and expressions of sanni masks from Sri Lanka, which were used in exorcism rituals to evoke 18 demons that symbolized different diseases. Surrounding Marcos are 18 masks variously rendered in reds, yellows, greens, and blues, representing military generals, government officials, and businessmen who shared in his greed. Beneath his scaly feet is the head of his wife, the notoriously ostentatious Imelda Marcos. At the center, Marcos bares his shiny white teeth, his mouth stuffed with puppets, their limby bodies emphasizing the grisly aspect of his cannibalistic tendencies. Despite Abad’s characterization of Marcos and his cabinet as sinful despots, the painting, brimming with color, is festive. Hundreds of thousands of buttons, sequins, and painted dots, sewn onto the surface of the painting, stand for the multitudinous Filipinos who suffered under his dictatorship.

Abad worked on the painting for 10 years, and it was shown for the first time at the Metropolitan Museum of Manila in 1995, almost a decade after Marcos was ousted. In this painting—which, like many of her works, is both figurative and abstract—she cited Indigenous art traditions from around the world to draw political solidarities between herself and those who lived “life in the margins” (as she titled one of her late paintings). Abad established these affinities by traveling, collecting diverse materials, and stitching them together at needlepoint, and she interwove these expressive styles born of the disparate struggles of the women she encountered around the world into works that exploded with life.

Abad’s retrospective at the Walker in 2023 was the most comprehensive showing of her work to date. It has traveled to San Francisco, is currently on view in New York (at MoMA PS1), and will make its way to Toronto later this year. The works included in the show draw attention to the many themes and styles that captured Abad’s interest over the course of her life—from African masks to marine life, abstraction to social realism, painting and embroidery to public art and works on paper. The show also explores her early life and her all-encompassing attitude toward art-making, as evidenced by photographs of her living spaces, which she decorated with her exuberantly colored tapestries and works-in-progress. Though Abad is primarily known for her abstractions today, the retrospective emphasizes her extensive travels and her social engagement as essential components of her work. “Pacita is the art,” Angela Adams, who curated Abad’s solo exhibition at the National Museum of Women in the Arts in 1994, said in an interview—a conclusion the retrospective encourages viewers to make.

Born in 1946 in Batanes, the northernmost province of the Philippines, to a large political family, Abad grew up in a house bustling with activity. During her university years, she became involved with the student movement opposing Marcos’s bid for reelection. Yet Marcos won handily, in what would later be described as the “dirtiest, most violent, and most corrupt election” in modern Philippine history. Abad’s family opposed his rule, and their home was machine-gunned early one morning. Nobody was hurt, but Abad left the country soon after.

She moved to San Francisco in her 20s. Living in the Haight-Ashbury neighborhood during the early 1970s, Abad encountered the last gasps of the counterculture and also met Jack Garrity, a development economist at Stanford whose work took him abroad for long stretches. In 1973, she joined him on an 11-month hitchhiking trip from Turkey to the Philippines, the first of many such trips together. By the end of her life in 2004, Abad would have lived and worked in over 60 countries.

San Francisco was formative for another reason. By the time of Abad’s arrival, the heyday for hippies in the Haight had passed, and increasingly, residents in the neighborhood were young, relatively affluent social liberals. But situated in the Bay Area, Abad also found herself in the midst of Ecuadoran, Korean, Cambodian, and Vietnamese immigrants and refugees, many of whom had wound up in California as a consequence of American wars overseas and who shared similar reasons for leaving home. As she developed a growing consciousness around the history of xenophobia and racism in the United States, she became involved in Asian American political activities in the Bay Area, such as supporting Filipino agricultural laborers on strike.

Abad was not a painter when she left the Philippines; in California, her early ambition was to become an immigration and human rights lawyer, though she eventually abandoned this idea, resolving instead to become an artist. She started an art practice in her late 20s and enrolled in her first painting class at 30. In her earliest and most rudimentary sketches and drawings, she already displayed an attention to the subtleties of texture, playing with the pockmarks on fruits and twigs and the consistencies of woven objects.

In her travels, she picked up a lifelong habit of collecting textiles local to the places she visited. In Foothill Cabin (1977), she painted the room she shared with Garrity in Palo Alto, the wall behind her bed decorated with the tessellating hexagonal design of a phulkari she brought home from Pakistan. Among the many woven traditions she encountered were Panamanian mola, Pakistani ralli quilts, and Bangladeshi kantha; she was also inspired by distinctive forms such as sumukhwa, a traditional style of Korean ink brush painting, and wayang, the Indonesian shadow puppet theater.

All of these techniques and styles found their way into her developing practice. Becoming curious about her work is becoming curious about the history and practice of textile-making by women the world over. As one example, Abad kept Hmong paj ntaub—story cloths sold to Western tourists—in her archive, and it’s possible to trace their influence in the flowers and animals she embroidered on clothing. Paj ntaub built on an ancient practice dating back to the third millennium BCE of embellishing clothing with floral and geometric designs. In the late 1970s, Hmong women in refugee camps pioneered a variation on the traditional paj ntaub that used similar motifs to tell stories of refugees escaping the aftermath of the Laotian Civil War. They also used brighter colors, with fresh access to industrial dyed threads in the camps. The story cloths were an assertion of Hmong cultural identity in the midst of displacement, inflected with a distinctly modern understanding of the international economy for attention and goods.

There are, without exaggeration, dozens of other traditions Abad integrated into her work. From mola, she seemed to copy the motif of patterning bold and bright lines with rickrack ribbons. In a period during which she was especially interested in wayang puppets, she made over 150 paintings rendering them. Her attraction to textiles was both intuitive and pragmatic; much like Faith Ringgold, inspired by the example of Tibetan thangkas, she had come to the realization that textiles could be rolled up and moved from place to place more easily than paintings on wood frames. Portability was essential, for she had decided by then to always be on the move.

Those who know Abad by her abstractions may be surprised to learn that some of her earliest works were social realist paintings. Around the late 1970s, she visited refugee camps in Nepal and Sudan and on the Thai-Cambodian border. Five social realist paintings in the retrospective reflect the documentary interest she took in these camps, where she interviewed journalists and relief administrators and conversed with refugees in French, learning of the treks they embarked on through jungles and mountains to arrive there. In her conversations with children—especially orphans—she noticed keenness to spend time with her, an adult who lavished them with attention, drawing them to prolong their interactions and make added attempts to circumvent language barriers. These paintings recall WPA-1era photographs by Dorothea Lange and Walker Evans in their journalistic impulse. During this period, Abad came to understand herself as a “political painter.”

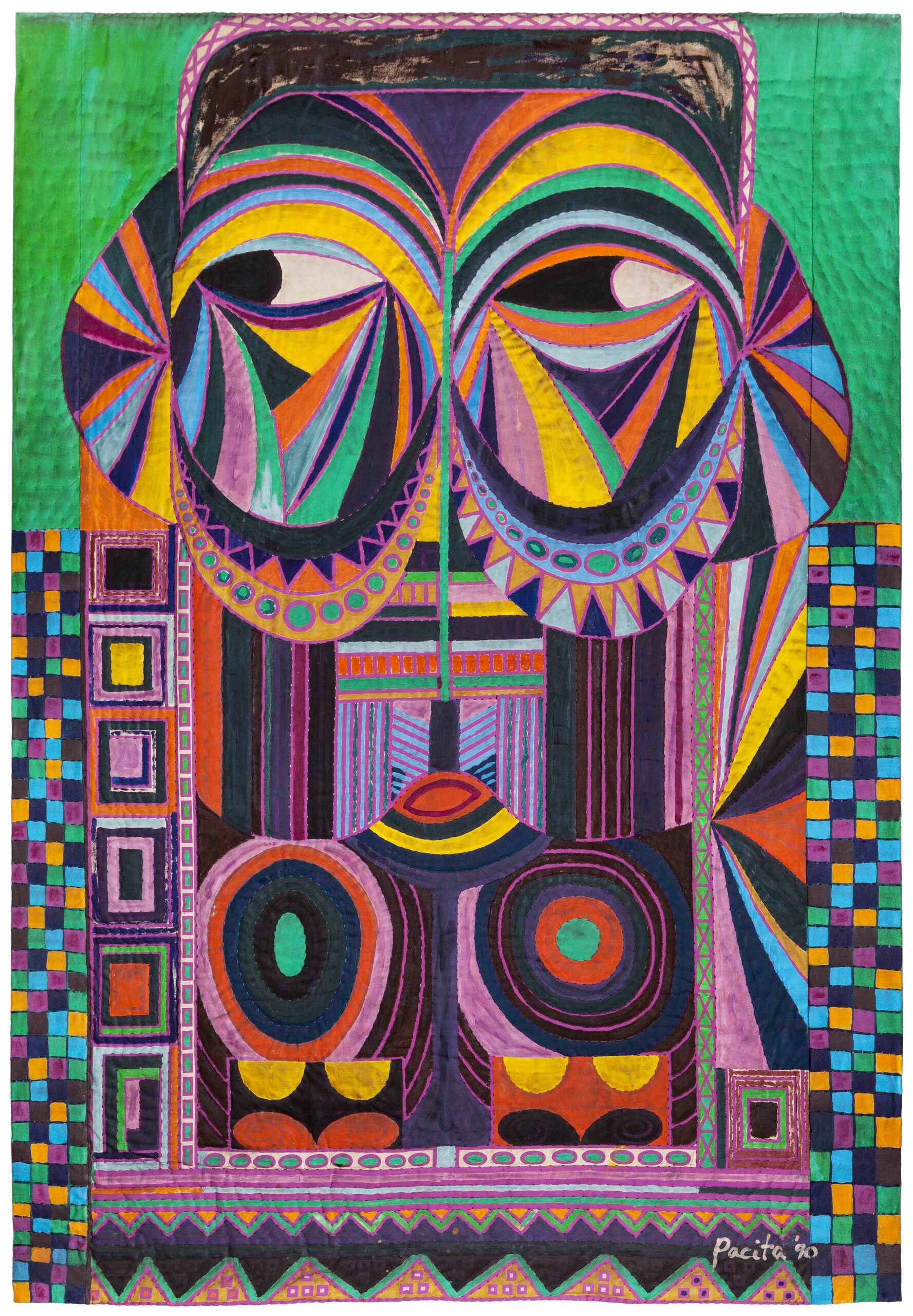

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →Her first artistic breakthrough arrived in the early 1980s, when she started taking an interest in masks across different cultural traditions, which she made with her new trapunto technique. She studied Sinhalese exorcism ritual masks from Sri Lanka and bifwebe face masks from the Songye and Luba tribes in the Congo, and she fashioned her own painted, stitched, and stuffed masks that she called Bacongo, in a nod to the influence of Central African masquerade traditions. These works are large, each over eight feet in height, and she combined the sharp angular contrasts and geometric abstraction of the carved masks with a tropical color palette. Juxtaposing loud colors against one another in the patterns that compose her masks, Abad said that she was “attracted to the dual concept of trying to be both who you are now, and what you can be.” Her comment echoes Stuart Hall’s definition of identity as a process “never complete, always in process, and always constituted within, not outside, representation.” Like Hall, Abad challenged the notion that tribal masks—which were often fetishized as symbols for entire tribal cultures and heritages—represented stable and unchanging identities, opting instead for her masks to be projects of identity creation.

Abad’s work with masks intensified at a moment when cultural practitioners in the Western art world were hotly embroiled in debates over how to understand the link between “tribal art”—referring monolithically to indigenous African, Oceanic, Asian, and American spiritual and artistic traditions—and Western modern and contemporary art. In December 1984, Abad returned to New York for Christmas and visited the Museum of Modern Art’s landmark exhibition “‘Primitivism’ in 20th Century Art: Affinity of the Tribal and the Modern.” The show was a curatorial feat, pairing hundreds of modernist pieces next to tribal objects. It generated controversy almost immediately: Critics condemned the show for privileging a Eurocentric historical timeline that placed artists like Picasso and Gauguin at the end of art history, and for deracinating tribal artifacts.

Abad shared their concerns. She saw the hierarchy between “high art” and “ethnographic, decorative craft” as just another colonial taxonomy. In the dozens of countries she visited, she was eager to learn about tribal cultures, traditions, and art, filling up her bags with beads and textiles at markets. She admired how people used buttons, shells, bones, feathers, and ribbons as creative ornamentation for their bodies, their dress, and their homes—even as many in the Western art world, under the sway of figures such as Clement Greenberg and Harold Rosenberg, increasingly placed a premium on “modernist” aesthetic attributes like purity and flatness, emphasizing painting to the exclusion of most other forms. This was the context in which Abad painted: Museums were making efforts to institutionalize work by “primitive,” “folk,” and “outsider” artists—all while prominent critics and curators promoted a future of modern art that would be more formal, more minimalist, and more detached from social and political problems. As MoMA’s “Primitivism” exhibition emphasized, these two tendencies were not always in tension but often mutually reinforced each other.

In Masks From Six Continents, a public art commission for the Washington, DC, Metro Center, that she completed in 1990, Abad produced mask paintings representing Europe, Asia, Australia, Africa, and North and South America. By giving them names like “Mayan Mask,” harking back to an ancient civilization; “Hopi Mask,” citing a particular tribe in southwestern North America; and “Subali,” a Hindu name denoting strength, she sought to destabilize modern racial and national identity categories. Meanwhile, she titled the European mask simply “European Mask,” calling attention to its emptiness.

Her mask paintings underlined the argument that Western modernism and “primitive” art did not need to be separated from one another. Still, even she at times revealed an inclination to romanticize pure, uncorrupted artistic traditions, as evidenced by her lifelong interest in finding Indigenous crafts untouched by colonialism and capitalism; returning to the Philippines, Abad was intent on locating tribal cloth that was “not Spanish-influenced, not Catholic-influenced.” Yet the traditions that she drew from, much like her own work, flowered at the unique crossroads of inherited craft and tourism, political upheaval, and the global flow of industrial goods.

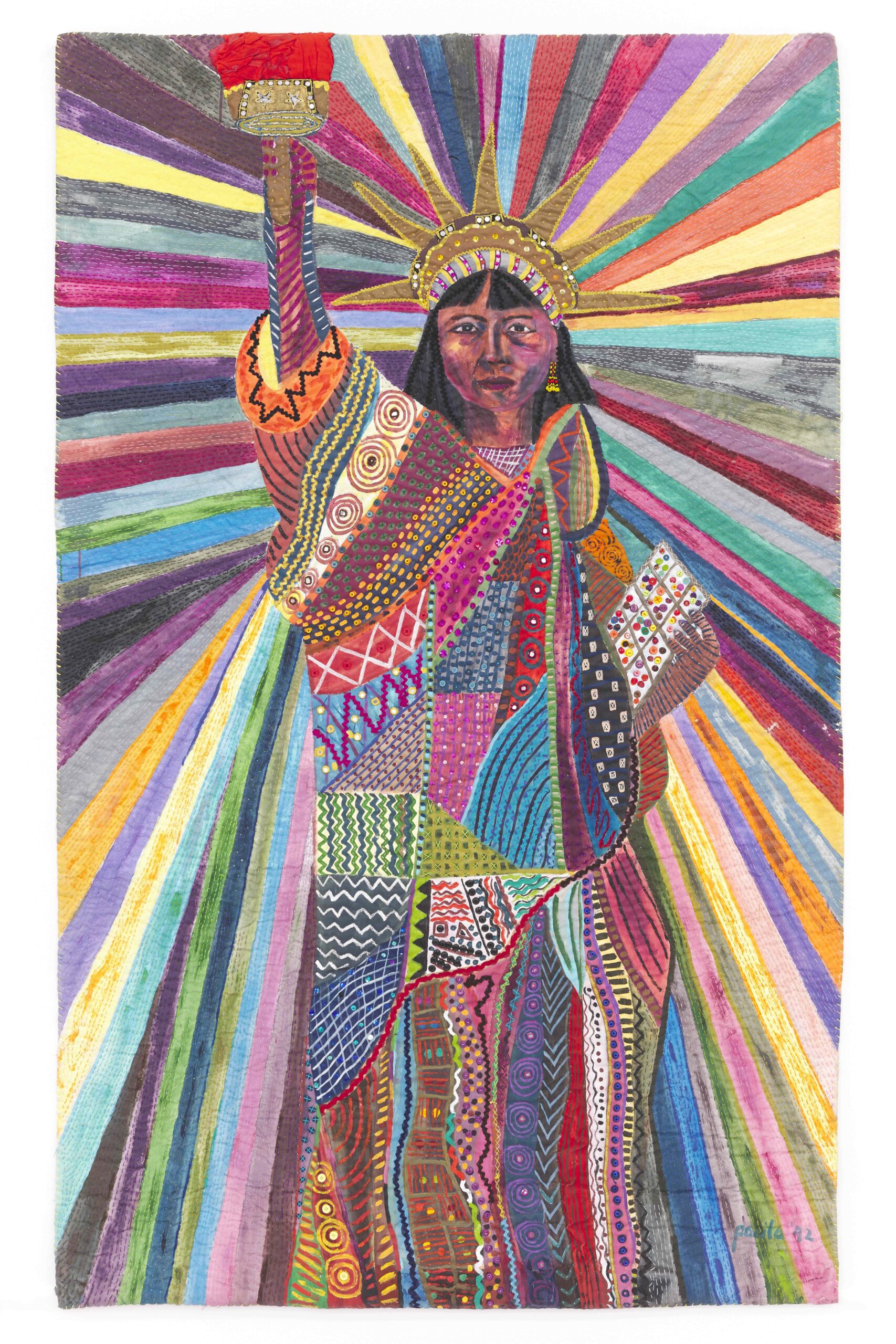

Although she soon turned away from the social realism that predominated in her early work, Abad continued to make figurative works—most notably her Immigrant Experience series, comprising some 20 paintings completed throughout the 1980s and ’90s. Whereas her social realist paintings resemble newsprint—flat and objective, and mostly bereft of color—her Immigrant Experience paintings are animated. These pieces feature triumphant and iconic emblems of empowerment: L.A. Liberty (1992) depicts a brown Asian woman in the guise of the Statue of Liberty, outfitted in a patterned quilt with multicolored beams shooting out around her.

She was attuned to the profusions of color that blossomed in immigrant, working-class neighborhoods that others might have regarded as underdeveloped zones absent of aesthetic significance. Attentive to the ways that ordinary people engaged in art-making practices, she represented such details as hand-painted deli signs advertising hot dogs, pretzels, and ice cream, and display cases stocked with hand-crafted goods. In an interview in 1991, Abad was asked what she had “contributed to this country as an artist.” She responded, without missing a beat: “Color! I have given it color!” These paintings show that this color came from an unpretentious passion for the vibrant, eye-catching products of everyday labor.

In the quieter portraits of daily life she painted on padded canvas, Abad portrayed such scenes as an Asian-owned laundry business or a Hispanic contractor’s storefront. In Korean Shopkeepers (1993), Abad reproduced the rich setting of a grocery store, with its fruits, flowers, and advertisements, applying a variety of materials, including buttons, sequins, beads, and yarn, to the surface of her trapunto. Painted in the aftermath of the 1992 Los Angeles uprising in response to the police beating of Rodney King—during which many Korean shops were vandalized—Abad envisioned a scene of harmony and solidarity.

In her later years, Abad began to receive more recognition in the United States for her work, and she was regularly included in group shows with other women artists of color, immigrant artists, and textile artists throughout the ’90s. By then, she was also several years into creating the work for which she is best known today: her abstract mixed-media paintings, which include both trapuntos and textile collages. A weakness of the Abad retrospective is that it slightly underrepresents this wonderful body of work—by far her most extensive—in the interest of providing a career-spanning survey. There’s a taste of the richness of this trove, and its connectedness to the rest of her work, in 100 Years of Freedom: From Batanes to Jolo (1998), a collage that integrates fabrics from every province of the Philippines. The ethnographic piece, with its draping triangular pieces of cloth, once fit snugly on a wall in her home in Singapore, a regular reminder of the hybridity of her motherland.

At the end of 2001, Abad was diagnosed with advanced lung cancer, and she spent much of the following year in Singapore undergoing treatment. She continued to work vigorously through her illness, beginning her last series of trapunto paintings, Endless Blues, which she worked on while listening to the music of Robert Cray and Miles Davis. Until the end of her life, she persisted in experimenting with new materials and techniques, creating drawings that she transformed into paper pulp works adorned with fabric, yarn, and found objects.

Abad, who was dedicated to art education and often led workshops teaching children and adults how to stitch and paint, would by all accounts have been excited to see her work displayed in museums. This exhibition affords her a level of recognition from the American art establishment that she never received while alive, and it is also an occasion for the celebration of the many other textile practices flourishing in the hands of women worldwide, which museums still so often struggle to appreciate on their own terms.

More from The Nation

What Comes After the Apocalypse? A Q&A With Joshua Oppenheimer What Comes After the Apocalypse? A Q&A With Joshua Oppenheimer

Oppenheimer’s latest film, The End, is a Golden Age, postapocalyptic musical crying out from the depths of the earth.

The Peculiar Case of Ignatius Donnelly The Peculiar Case of Ignatius Donnelly

The Minnesota politician presents a riddle for historians. He was a beloved populist but also a crackpot conspiracist. Were his politics tainted by his strange beliefs?

The Agony of Aaron Rodgers The Agony of Aaron Rodgers

Is he the world’s most interesting athlete or is he just a washed-up crackpot?

Can You Understand Ireland Through One Family’s Terrible Secret? Can You Understand Ireland Through One Family’s Terrible Secret?

In Missing Persons, Clair Wills's intimate story of institutionalized Irish women and children, shows how a family's history and a nation’s history run in parallel.

Peter Schjeldahl’s Pleasure Principle Peter Schjeldahl’s Pleasure Principle

His art criticism fixated on the narcissism of the entire enterprise. But over six decades, his work proved that a critic could be an artist too.

How the Western Literary Canon Made the World Worse How the Western Literary Canon Made the World Worse

A talk with Dionne Brand about her recent book, Salvage, which looks at how the classic texts of Anglo-American fiction helped abet the crimes of capitalism, colonialism, and more...