A Paean to Nonhuman Life

In Lydia Millet’s We Loved It All, she compels readers to decenter human experience in the stories we tell about the natural world.

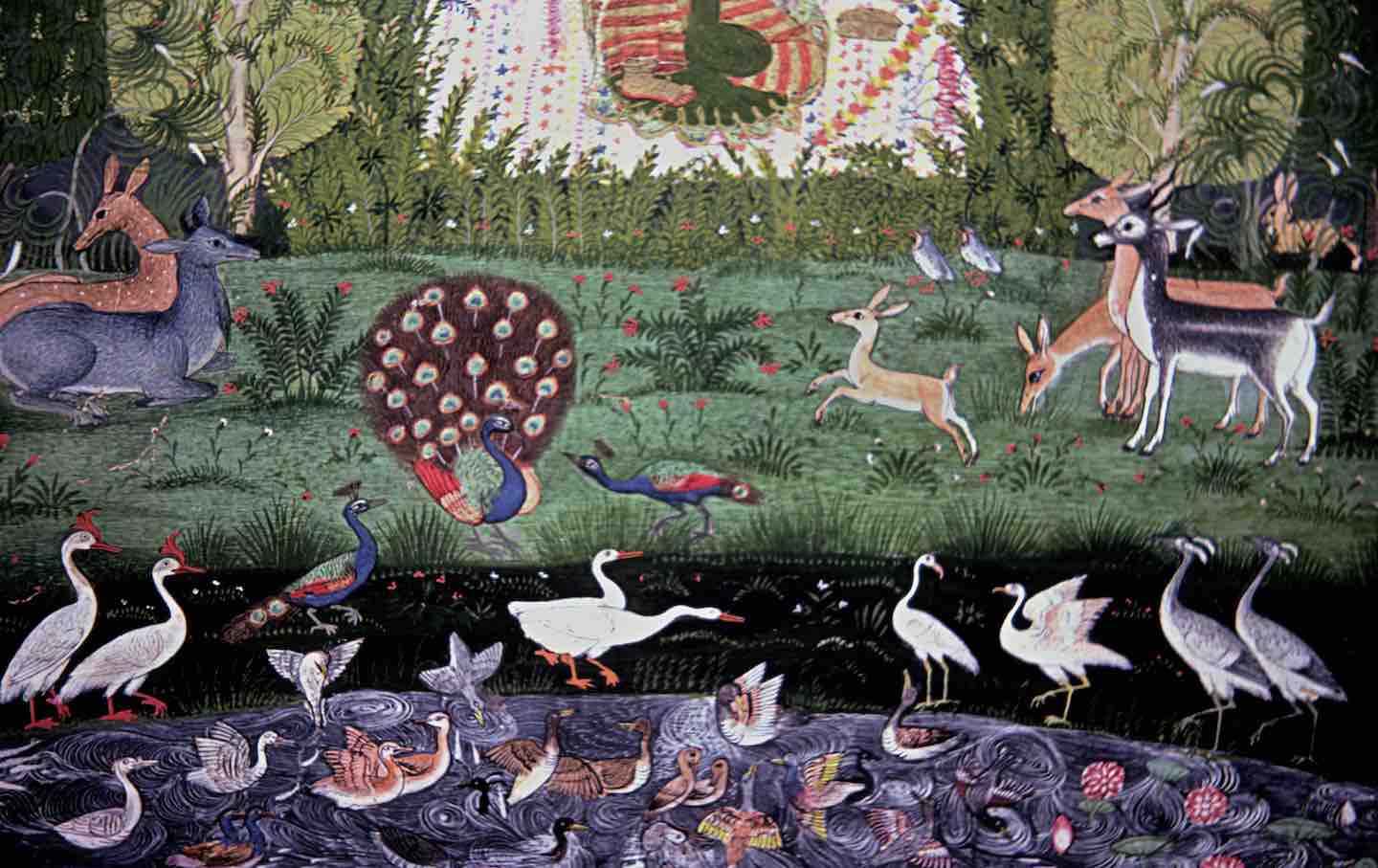

Detail of Bundi School, 17th century, National Museum, New Delhi, India.

(Photo by: Shalini Saran / IndiaPictures / Universal Images Group via Getty Images)

When Lydia Millet was a child and her guinea pig Trudy died, she asked her parents if anyone had ever committed suicide because of a pet’s death. “Probably not,” they responded diplomatically. For a few hours, Millet stared at her bedroom wall, sobbing and inconsolable. Then the grief passed: “It had gotten boring,” she recalls, “and I was quite hungry.”

Books in review

We Loved It All: A Memory of Life

Buy this bookMillet’s first work of nonfiction, We Loved It All: A Memory Life, is a sweeping study of climate change, greed, human hubris, loss, and the possible end of life as we know it, but it begins with moments like this, told from the perspective of youth. The moods of childhood may be imperious, hysterical, and yielding, but they may also reveal parts of the world that adults have been trained to ignore. Those feelings of grief about Trudy, for example, were also feelings of guilt. Like many children, Millet often forgot to remove piles of the animal’s droppings from her cage or, too lazy to retrieve lettuce from the fridge, fed her pellets from a plastic bag. But Trudy was “just a guinea pig,” Millet assured herself, reciting a line she’d heard from adults. What did she care?

There is a risk, in examining a pet’s preference for lettuce or hay, of appearing excessively concerned about a category of domesticated animal that humans already lavish uncommon attention on. But Millet’s focus is more diffuse: She’s interested in the received ideas about nonhuman life that we know, instinctively, to be overstated and false. Take that inflection: “just a guinea pig” (or dog, cat, bird, cow, etc.). What does it really mean? Consider that a crow can remember a human’s face and even identify, based on one’s expression, whether that person is friendly or hostile. It might be foolish to project the emotions we feel onto animals, but it seems equally absurd, Millet writes, to “presume that people have exclusive access to impulses like love or jealousy.” And by denying that other forms of life have interiority and depth, we’ve deprived ourselves of the opportunity to, as Millet puts it, “search into an abyss of information we’ve barely begun to plumb.”

We Loved It All is an attempt to examine that abyss—the expanse of life we usually relegate to the background of our own. Instead of transforming animals and plants into objects of projection, symbols of our own loneliness or autonomy or avarice, she surveys the strangeness of nonhumans, like the eccentric mating rituals of spiny echidnas or finches that talk to their embryos. Weaving together memoir, cultural critique, and scientific journalism, Millet tells a story of human existence and its transformation alongside nonhuman existence. It’s both capacious and personal, linking memories from Millet’s childhood and later marriage to questions about the planet, time, systems of governance and trade, machines, and mass extinction.

Millet’s writing has a certain urgency, of course, because many of these forms of life are swiftly disappearing. “Maybe we haven’t spoken up for the others partly because of the unconscious, innate quality of our ties with them,” she observes. “Possibly we need the telescopic view—the distance of forgetting and the jolt of recognition as a remembrance surfaces—to know what we adore.”

Behind Millet’s quest to catalog the multitude of life is a deceptively simple hypothesis: To get people to do something about the imminent collapse of our natural systems, we might need a new method of persuasion. Perhaps instead of appealing to our own self-interest, to moralism or economic pragmatism, we need to start with something more fundamental: an appeal to our attention. If this sounds obvious and meek (just look at the flowers!), consider that, in a society obsessed with wealth, power, and productivity, the attempt to sustain an interest in things that don’t clearly advantage us, that aren’t a means of self-improvement or amassing resources, is no easy feat.

Noticing the presence of others among us won’t erase the damage that we’ve already done; nor is it, on its own, a solution or an end. But it may be the best place to begin. After all, what we pay attention to, we tend to care for and even love; and what we love, we make sure doesn’t disappear.

Writing about animals, plants, insects, fungi, and other life-forms that are, to varying degrees, speechless and unreachable is exceptionally difficult because of all the things we don’t know. How does a fly experience time? Does a frog feel depressed when its mating calls aren’t returned? What’s it like to see colors in the ultraviolet spectrum? Or to hear the distant rumblings of a storm hundreds of miles away? Or to be the very last Pinta Island tortoise? How to write from the perspective of what we don’t understand?

Our answer seems to be, simply, don’t. In most novels and movies, nature shows up to set a mood, like the rainstorm that presages a romantic confession. Sometimes, nonhuman life becomes a conduit for a lonely, grieving, or otherwise lost person to find herself. Occasionally, we imagine other creatures as humans, as in the children’s books populated by amiable or mischievous talking animals.

Millet, who works as an editor and staff writer at the Center for Biological Diversity, has spent much of her career reckoning with the challenges of writing about the nonhuman world. Her fiction often imagines human encounters with other creatures, real or fantastical. In Mermaids in Paradise, a huge resort company tries to turn a colony of mermaids into a theme park; in Omnivores, a man’s fixation with collecting dead insects evolves into feverish cruelty. Her latest novel, Dinosaurs, follows a benign and somewhat hapless bachelor named Gil as he looks after his neighbors’ children, cares for a grieving widow, and volunteers at a domestic violence shelter, where he escorts the women on shopping trips. Gil takes an analogous interest in the animal life around him: the turquoise and purple hummingbirds that float like “hovering jewels,” the woodpeckers that nest in underground holes, the family of hawks that perch on saguaro cacti. When several dead quail appear in his yard, Gil tracks down the hunter and tells him: “You need to stop shooting my birds.”

In We Loved It All, Millet continues to record the ways in which human and nonhuman lives are intertwined. Often, the story she tells is tragic: As soon as people interact with other species, we cause swift and irreparable harm. This typically occurs when we conceive of the beings around us as tools—a means to an end. Take the 19th century’s “pit ponies,” the disturbing moniker for horses who spent their entire lives in mines and never saw light from the sun; or fistulated cows, whom we cut open and plug with plastic so we can stick our arms into their bodies and retrieve healthy bacteria and other microbes to treat digestive issues in farm animals.

Millet suggests an alternative to this default attitude in what she calls “negative capability,” a term she borrows from John Keats and defines as “a state of living in uncertainty, mystification, and receptivity that allows us to deeply imagine the perspectives of others.” This is something we consider an admirable capacity when applied to humans, but that we rarely encourage outside of our own kin. Instead, we tend to view people who care deeply for plants and animals as temperamentally different from, and perhaps in conflict with, those concerned with the interior drama and suffering of other humans. Millet’s point is that the very act of suspending one’s sense of self—receding, momentarily, from our own ego enough to receive flashes of what it might be like to be someone or something else—is a skill we train through habit. It allows us to enter into a closer camaraderie not only with other people but with other creatures as well. And perhaps it also lets us connect with a shared sense of life.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →One challenge that Millet faces in writing a story that isn’t driven by an individual’s ambition or desire or foibles is just how unaccustomed we are to this mode. The stories we read or watch typically follow a pattern in which “a victorious self,” Millet writes, “rises ascendant, against all odds, over hostile, misguided, or otherwise inferior others.” We are taught to emulate this arc in our own lives, to bend our environment to our will. In We Loved It All, Millet doesn’t follow a single character or even a central argument. Instead, she’s propelled by the quest to freshly see what’s deceivingly familiar.

Millet often describes nonhuman life as if she were an alien plopped on Earth, writing a letter home. “Some are covered in lustrous feathers, silver scales, or elaborate segments of armored plates,” she writes of animals. “Some look like translucent bells, floating in water and trailing a mass of curling ribbons.” Animals are so fabulous, Millet observes, that children often think “they might have been invented purely for our delight.” Her arresting and odd descriptions remind us of that feeling.

Millet asks if we might apply a similar sense of wonder to our daily routines. Just as we’ve become anesthetized to the magical strangeness of animals, we tend to take for granted the technology, beliefs, and customs that guide how we move through the world. To this end, she makes a series of unusual connections designed to kindle surprise. In one chapter, Millet leaps between a number of subjects: the invention of the Walkman; how personal soundtracks encourage us to narrate our own stories; her many beautiful ex-boyfriends; romance as the pursuit of self-flattery; the use of pools as early mirrors; ancient ground sloths; frames and social media; the challenge that octopuses face in passing down generational knowledge. These sections are all loosely collected around our obsession with individuality and the failure to commune and connect outside of the self.

And yet, with no building toward a conclusive theory, these associations can often feel dizzying, a merry-go-round of ideas, facts, and scenes. As in many contemporary novels, stylized in fragmented paragraphs and dangling aphorisms, we’re left to pull the threads together. We rarely feel the cathartic pleasure of synthesis. Instead, we’re spun around and told to look here and there—and sometimes there is simply too much to see.

Tying together so much information also invites, and even requires, simplification. Millet addresses our collective species as “we,” a technique likely meant to erode the distance between reader and subject, having us share in the responsibility and immediacy of climate change. But blending together such a vast audience—and understanding humanity as a single entity—obscures much of the texture and variation to human life. Sometimes, Millet is upfront about the limits of her analysis, careful to note that she is speaking about and to the Western middle class; but it’s clear, even when she doesn’t make this explicit, that most of her observations about play, art, childhood, and work are drawn from this particular set of lives.

Still, for all the challenges of writing what Millet has called an “anti-memoir,” it seems a worthy and ambitious endeavor. Part of her proposition is that the type of story we’ve become accustomed to seeing, the one about a single person succeeding or failing, is making us sick and miserable. This type of story encourages us to see everything, from animals to plants to people, as an instrument to realize our individual ends; this leads to the overconsumption of resources, the mass destruction of our environment, and intense human loneliness. So maybe we need “a respite from storytelling,” Millet suggests, and an opportunity to “simply to absorb the presence of the world and our presence within it.” The hope is that, if we manage to make room for another type of story, there might be a way out of confronting what seems so obvious and uncomfortable: the possibility of an end.

More from The Nation

TikTok’s Incomplete Story TikTok’s Incomplete Story

The company has transformed the very nature of social media, and in the process it has mutated as well—from tech unicorn to geopolitical chesspiece.

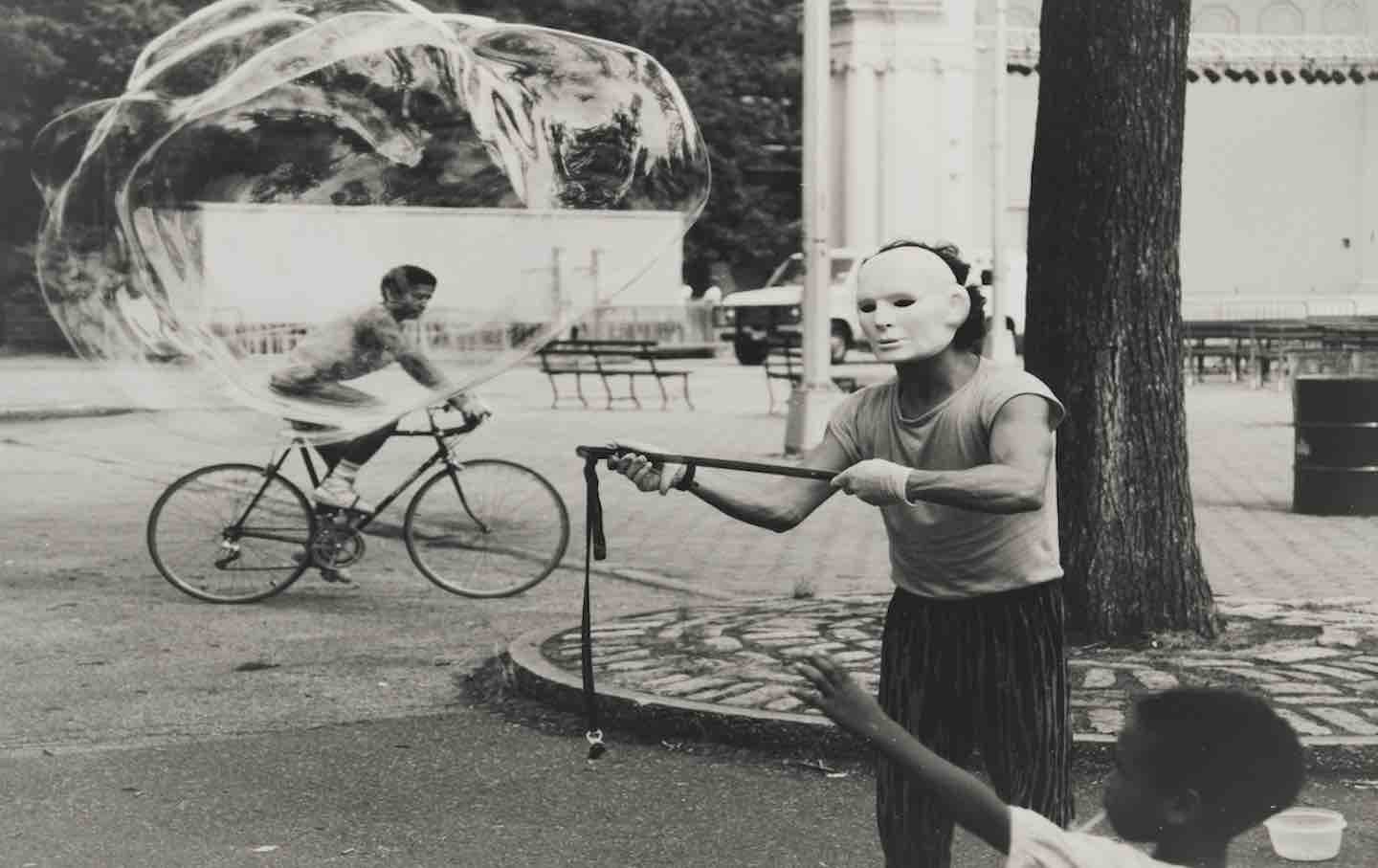

Did We Get the History of Modern American Art Wrong? Did We Get the History of Modern American Art Wrong?

The standard story of 1960s arts is one of Abstract Expressionism leading into Pop Art and minimalism. A Whitney show proposes an altogether different one centered on surrealism.

The Bleak History of the American Work Ethic The Bleak History of the American Work Ethic

In Make Your Own Job, Erik Baker shows just how long Americans have scrambled to pile work on top of work—and at what cost.

The Banal Spectacle of “Avatar: Fire and Ash” The Banal Spectacle of “Avatar: Fire and Ash”

Has James Cameron’s epic sci-fi series run aground?

The Dislocations of Shuang Xuetao The Dislocations of Shuang Xuetao

The Chinese writer’s fiction details how the country transformed on an intimate level after the Cultural Revolution.

An Absurdist Novel That Tries to Make Sense of the Ukraine War An Absurdist Novel That Tries to Make Sense of the Ukraine War

Maria Reva’s Endling is at once a postmodern caper and an autobiographical work that explores how ordinary people navigate a catastrophe.