The Roots of Trans Women’s Unjust Treatment

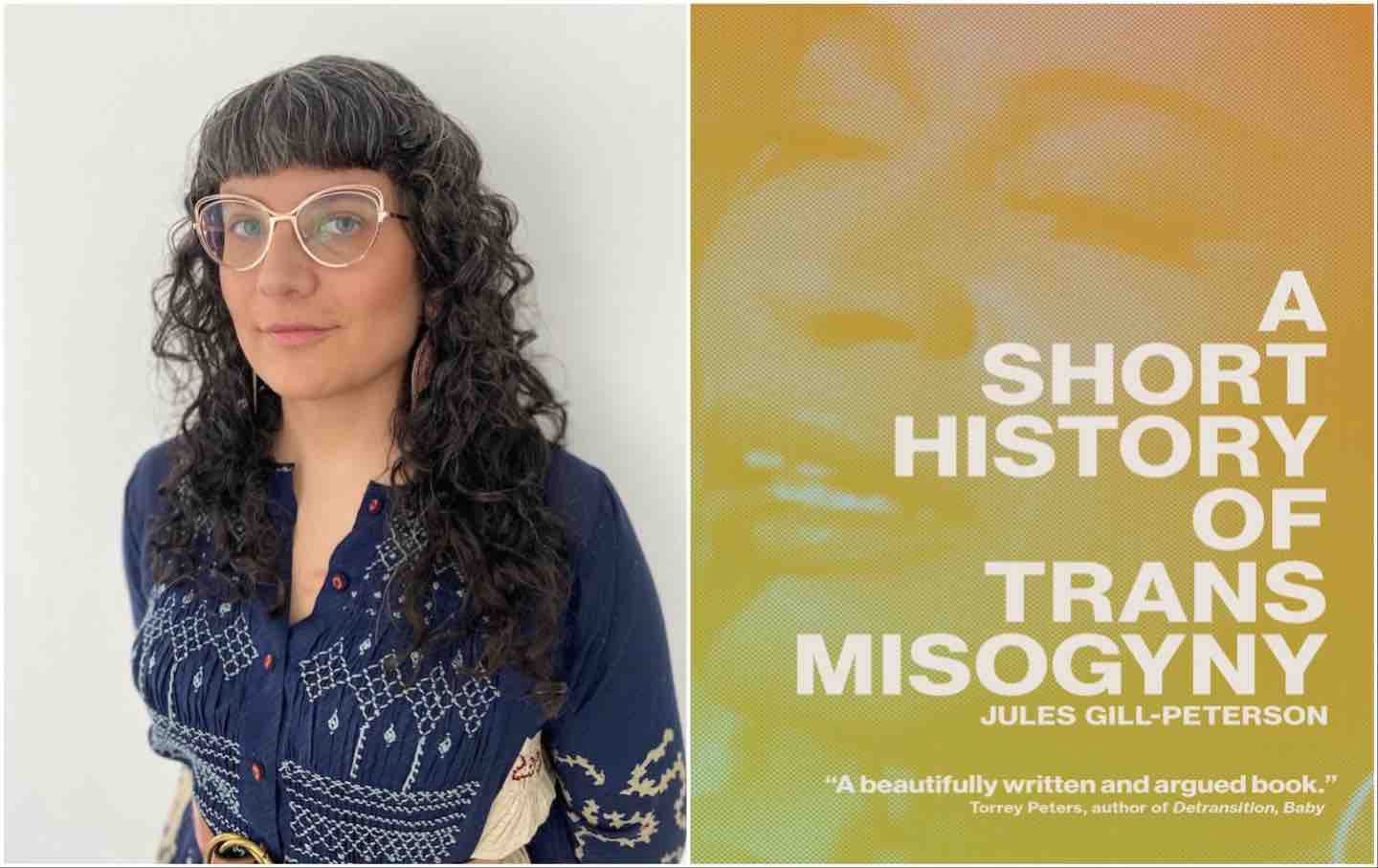

Jules Gill-Peterson’s A Short History of Trans Misogyny is an essential primer on the colonial and racist origins of hatred against those who refuse to adhere to the gender binary.

There’s a particular flavor of hatred directed at trans women: You are hated for being trans, and then hated again for your femininity. In her 2007 book Whipping Girl, Julia Serano offered a useful term for this: trans misogyny. Now Jules Gill-Peterson, the author of Histories of the Transgender Child, gives us a much-needed account of the genesis of trans misogyny and its subsequent history.

Books in review

A Short History of Trans Misogyny

Buy this bookMisogyny, for Gill-Peterson, is a structural phenomenon: a pervasive form of violence that works its way from the bottom up, affecting, most frequently, women at the lowest stratum of one or another social hierarchy. Its full force lands on women who are also poor, or racially othered, or disabled—or trans. At the same time, misogyny promises protection to those women further up the social ladder who are willing to align themselves with the exclusion of their less fortunate sisters.

“Woman” is a social category with histories, and so is “transgender.” It is tempting, as someone who thinks of herself as a trans woman, to imagine that we have always existed, and exist everywhere. One would think we would have learned by now the limits and even dangers for social movements of invoking this sort of essence that flattens out differences. Gill-Peterson offers, instead, the useful concept of the trans-feminized, meaning those who are designated as such by institutional power, regardless of how they might perceive themselves.

The trans-feminized is a social category, not an identity. This approach reminds me of the “labeling theory” popularized by Howard Becker in his 1963 book Outsiders. Becker was a jazz musician before becoming a sociologist. His labeling theory addresses how groups labeled deviant outsiders by the law, the media, or sociologists may have very different ways of perceiving and labeling themselves. It is as if we keep forgetting to ask where social categories come from and so act as if they are just given facts. By contrast, Gill-Peterson wants to uncover the particular histories of the trans woman as a social category rather than an eternal identity.

I sincerely believe that “transsexual woman” is what I am, but the label precedes me. In actuality, I accept, resist, or modify the social categories available to me. As we all do, although some have access only to categories that penalize them for existing.

For Gill-Peterson, the practices of identifying, classifying, and controlling the categories of those considered gender-deviant began as part of a colonial project of managing subject populations. Consider, for example, the fate of the Joya. This was the name used by Spanish missionaries and soldiers for a subset of the Indigenous peoples of what is now Southern California. They dressed as women and did women’s work, and they had special responsibilities for the care of the dead.

The Spanish, forcing their own social categories upon them, considered the Joya sodomites. Many were slaughtered, ripped apart by dogs. Others were forced to wear men’s clothes and do men’s labor for missionaries. In studying the fate of the Joya, Deborah Miranda coined the term “gendercide,” meaning the systematic erasure of gender. The apparent universality of “gender” is an effect of colonial violence and erasure.

Were the Joya trans women? That would be to impute an identity to them that would have made no sense in the social life of their people. It repeats the colonial gesture of reading another way of life through terms imposed from without. Were they victims of trans misogyny? That could also tip over into an ahistorical view. What Gill-Peterson does instead is show how contemporary trans misogyny builds out of and evolves from such colonial practices.

The Hijra in Northern India, to give another example, were not eradicated by British colonialism, but it’s not as if the colonizers didn’t try. The Hijra were unassimilable to British nostrums of sex, gender, religion, and family, but also of labor. As Gill-Peterson writes, “Hijra were so feminine they were regarded as ungovernable.” In the 1860s, the British set out to reduce them by breaking up their disciple system, outlawing their property inheritance, making them register with the police, limiting their travel, and criminalizing their mode of dress and public performance.

The trans misogyny of today also emerges out of colonial practices of policing populations that were then applied closer to home in the metropole. In 1836, a Black sex worker named Mary Jones was arrested in New York City. Neither sex work nor interracial sex was illegal in New York at the time, but during her encounter with one Robert Haslem, she stole his wallet. Her trial became a sensation in the press. I insist on calling Mary “she,” but to the press and the courts, Mary was a man. In a popular illustration of the time, she is the “man monster.”

It’s tempting to claim Mary as a Black trans sex-worker ancestor, as the artist Tourmaline does in her video work Salacia. And in the cultural realm, why not? For the historian, there are other things to dwell on in this case. For Mary Jones, appearing as a woman might have been more of a way to make a living than an identity. The furor surrounding her trial had as much to do with the pro-slavery sentiment at the time, which mobilized panic about Blackness as undermining the sexual, gendered, and economic order, particularly in the urban landscape of New York, already perceived as a veritable Sodom.

Like the Joya or the Hijra, one can see Mary Jones as someone who in contemporary terms was trans-feminized by a regime of social power that wanted a docile population available for work under a gendered division of labor that they didn’t fit into. Nor did they fit in with the way social reproduction was intended to work, where sexuality would be restricted to the reproduction of labor. From the perspective of the present, the concept of trans-feminization allows for comparative thinking, but without imputing a common transgender identity.

Even closer to our own time, the imputation of a transgender identity to trans-feminized people might not be helpful. Gill-Peterson offers a reading of John Rechy’s pioneering gay novel City of Night (1963), specifically the passages about the character Miss Destiny, a Los Angeles “queen.” As Gill-Peterson reads Rechy, Miss Destiny doesn’t have an identity so much as a theology: “She has two bodies—one given to her in the flesh and one aspirational—and she claims to transcend the material world with its tawdry notions of maleness.”

The medieval doctrine of the king’s two bodies, funnily enough, came out of contemporary attempts to place intersex, or “hermaphrodite,” bodies in the gendered order of the time. So it might not be too much of a stretch to imagine the queen’s two bodies when trying to imagine the world of trans-feminized people who thought of themselves as street queens.

Gill-Peterson’s reading of Miss Destiny opens toward an account of the figure of the queen in pre-Stonewall homosexual culture. Esther Newton’s 1972 book about professional drag artists, Mother Camp, offered an ethnography of homosexual life in which the drag queen was a figure at both the top and the bottom of the gay social order. The professional drag artist was a revered figure, but one who took wig and makeup off after the show. The street queen lived her womanhood, and was ostracized for it.

Rechy found Miss Destiny among those who, like himself, lived as hustlers—at the bottom of the heap. If one is to understand gender as a totality, maybe those most marginalized by it hold the key to it. Gill-Peterson asks: “Why has the central symbol of gay culture long been trans femininity? What if the trans queens of the gay world were actual queens, sovereign figures meant to lead all sorts of exiles from American culture labeled deviant?”

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →This opens up a space to wonder whether the politicizing of homosexual life by gay liberation also had an unintended consequence in its secularization. As gay liberation was diluted down to more acceptable expressions of gay pride and gay rights, the street queen—the one at the bottom of gay life—was left behind. “The fall of the trans queens, Gill-Peterson writes, was “a spiritual sacrilege.”

The celebration of a homosexual masculinity weakened the historic connection between the gay man and the street queen. What emerged was a model of homosexuality as one of the more or less acceptable norms of civil life, so long as sexuality itself was sequestered to private life. The double of this normative gayness is a normative version of transness—the transsexual. Those with the resources to work past the legal, medical, and psychiatric gatekeepers might be allowed to transition, so long as their goal was a conventional gender for a conventional life.

The concept of trans-feminization enables Gill-Peterson to group together strategies of institutional surveillance, coercion, and control of other-gendered bodies without the assumption of an essential identity. Those of us struggling against such forms of control then have a kind of negative solidarity, in that the regimes we confront deploy related strategies against us. But what would be a way to affirm our various ways of embodying what trans-feminization can only perceive from without?

Gill-Peterson takes her cue from the travesti movements of Latin America, which are not assimilable to the Anglocentric idea of the transgender woman. She turns to the Peruvian gender-studies scholar Malú Machuca Rose: “Travesti is the refusal to be trans, the refusal to be a woman, the refusal to be intelligible.”

While there are worse things than a trans-inclusive feminism, Gill-Peterson wonders if it’s worth the price of inclusion to downplay not just our differences but also our excess. Whatever else is said against those who are trans-feminized, we are always too much. We’re extra. And maybe we want to be. Maybe we might want, Gill-Peterson argues, to take “real pleasure in a trans-feminine body—affirming the desire to be feminine, to be desired by men, or to enjoy having sex.”

As Gill-Peterson says, “The dolls hold all the receipts.” The “doll” is what some contemporary versions of Rechy’s queens call themselves. All dolls are trans-feminized, but not all of the trans-feminized are dolls. The dolls are artists of high femme style, attracted mostly to men, familiar with sex work, inhabitants of night life. The arbiters and authorities among the dolls are usually Black. The dolls are at the furthest remove from the academic study of gender, and they’re often left behind whenever “transgender identity” is discussed. Gill-Peterson does them the honor of centering them for any further attempts to articulate who the objects of tran-feminization are within American life.

More from The Nation

What Comes After the Apocalypse? A Q&A With Joshua Oppenheimer What Comes After the Apocalypse? A Q&A With Joshua Oppenheimer

Oppenheimer’s latest film, The End, is a Golden Age, postapocalyptic musical crying out from the depths of the earth.

The Peculiar Case of Ignatius Donnelly The Peculiar Case of Ignatius Donnelly

The Minnesota politician presents a riddle for historians. He was a beloved populist but also a crackpot conspiracist. Were his politics tainted by his strange beliefs?

The Agony of Aaron Rodgers The Agony of Aaron Rodgers

Is he the world’s most interesting athlete or is he just a washed-up crackpot?

Can You Understand Ireland Through One Family’s Terrible Secret? Can You Understand Ireland Through One Family’s Terrible Secret?

In Missing Persons, Clair Wills's intimate story of institutionalized Irish women and children, shows how a family's history and a nation’s history run in parallel.

Peter Schjeldahl’s Pleasure Principle Peter Schjeldahl’s Pleasure Principle

His art criticism fixated on the narcissism of the entire enterprise. But over six decades, his work proved that a critic could be an artist too.

How the Western Literary Canon Made the World Worse How the Western Literary Canon Made the World Worse

A talk with Dionne Brand about her recent book, Salvage, which looks at how the classic texts of Anglo-American fiction helped abet the crimes of capitalism, colonialism, and more...