How Historical Fiction Redefined the Literary Canon

In contemporary publishing, novels fixated on the past rather than the present have garnered the most attention and prestige.

The 68th National Book Awards at Cipriani Wall Street, 2017.

(Photo by Dimitrios Kambouris/Getty Images)

On Friday, the judges of the National Book Awards will announce the long list for this year’s prize for fiction. On Monday, the Booker Prize jury will winnow their own long list down to just six finalists. And while betting on literary prizes is something of a fool’s game, odds are both lists will cover quite a lot of historical ground. The likely honorees include Percival Everett’s James, set in the antebellum South; Tommy Orange’s Wandering Stars, which spans 150 years, beginning in the 1860s; Taffy Brodesser-Akner’s Long Island Compromise, split between 1980, World War II, and the present; and Claire Messud’s This Strange Eventful History, whose multigenerational plot runs from 1940 to 2010. Two different prizes, with two different juries, with two lists of books that—I’d wager—will have a lot in common.

That’s because, over the last several decades, a quiet revolution has taken place in American fiction: The novels recognized by major literary prizes have largely abandoned the present in favor of the past. Contemporary fiction has never been less contemporary.

If we look back to the middle of the 20th century, we can see that the kinds of books that were short-listed for the Pulitzer Prize or the National Book Award then were mostly about contemporary life: J.D. Salinger’s Catcher in the Rye, Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man, and a host of others by the likes of Saul Bellow, John Cheever, and John Updike. And these aren’t outliers. Between 1950 and 1980, about half of the novels short-listed for these and the National Book Critics Circle Award were set in the present, narrating “the way we live now” in all its complexity.

Fast-forward to the present, and the past has taken over. A historical novel has won the Pulitzer Prize for fiction in 12 out of the last 15 years, and historical fiction has made up 70 percent of all novels short-listed for these three major American prizes since the turn of the 21st century. Today, writers like Colson Whitehead, Viet Thanh Nguyen, Louise Erdrich, and Hernan Diaz are less interested in the way we live now than the way we were.

But this generation of prize-winning novelists is different from their forebears in another major way—they’re a lot less white. American literature’s overwhelming turn toward the historical past has both motivated, and been motivated by, the increasing recognition of Black, Asian American, Latinx, and Indigenous writers in the literary field. Over the past five decades, writers of color have been celebrated, prized, and canonized almost exclusively for the writing of historical fiction: narratives of war, immigration, colonialism, and enslavement that span generations and honor previously disregarded histories. Of the top 10 most-taught novels by writers of color published after 1945, eight are works of historical fiction. Of the 54 novels by writers of color to be short-listed for a major American prize between 1980 and 2010, all but four are works of historical fiction.

Richard Jean So has recently argued that racial disparities in 20th-century publishing constituted a kind of “cultural redlining,” wherein writers of color were largely unrepresented. While the literary canon of the early 21st century is markedly more inclusive, a different sort of redlining still exists: not the outright refusal of literary institutions to enfranchise writers of color, but a selective elevation that enfranchises those writers only in a single sector of the literary field. Though the pantheon of American literature may be more racially and ethnically diverse than it has ever been, the criteria that consecrate minority writers have never been more homogeneous. How did the definition of literary excellence become so narrow?

Beginning in the 1980s, a number of key literary institutions transformed in ways that either expressly or implicitly promoted historical fiction as contemporary literature’s most prestigious and politically important genre. These included creative writing programs, literary agents, and the funding organizations, like the National Endowment of the Arts, that encouraged authors to write fictionalized versions of their family histories; major literary awards that prized historical fiction above all other genres and concentrated that prestige in a handful of historical settings; literary scholars who placed the work of historical recovery at the very heart of their method; and university English departments that recalibrated syllabi toward fictions of the past. These transformations impacted the careers of 20th-century writers like Toni Morrison, Leslie Marmon Silko, and Julia Alvarez, and they shaped those of 21st-century writers like Colson Whitehead, Julie Otsuka, Jesmyn Ward, and Tommy Orange.

In many ways, Morrison stands as the chief figure of this shift in literary taste. By virtually any measure, the author’s 1987 masterpiece, Beloved, is the single most canonized work of contemporary American fiction. Beloved is among the most-taught novels in university courses and the contemporary novel most cited by scholars. Morrison’s haunting book on American slavery stands out from the contemporary literary canon even as it typifies that canon’s thematic and aesthetic preoccupations. The novel takes place during a crucial moment in the nation’s past, documenting the horrors of history with a startling closeness and tracing their resonances across several generations. In the decades since its publication, Beloved has proved a model for a diverse group of writers interested in narrating the past, as well as a touchstone for teachers and scholars invested in recovering that past.

When Beloved became a finalist for the National Book Award in the late 1980s, Morrison was one of only a handful of Black novelists to be short-listed for the prize in the decades since Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man won it in the early 1950s. Whereas Invisible Man opens with the protagonist being expelled from college, following him as he is employed to paint the world “Optic White,” Beloved closes with Morrison’s own young protagonist, Denver, at the precipice of college admission, so that she might write a different story with the ink her mother, Sethe, was forced to make. While the tale the invisible man tells is his own, its setting the contemporary world in which he lives, Denver’s narrative is one of (what Morrison calls) rememory, of grappling with the world that came before her.

Though neither Morrison nor Beloved inaugurated a shift in literary value single-handedly, novel and novelist alike came to exemplify it for a generation of readers, teachers, scholars, and writers that followed. One way of understanding the cultural history of the last five decades is as the story of how American literature moved from Ellison to Morrison to where we are now—of how, in other words, the past came to supplant the present in contemporary American fiction.

In the 1980s and 1990s, Fredric Jameson argued that one of the many failings of contemporary historical fiction was its “omnivorous…historicism,” its “random cannibalization of all the styles of the past.” More than 20 years later, Jameson doubled down on that claim in an essay titled “The Historical Novel Today, or, Is It Still Possible?” He lamented that “the historical novel seems doomed to make arbitrary selections from the great menu of the past, so many differing and colorful segments or periods catering to the historicist taste, and all now…more or less equal in value.” Yet this critique fails to register just how selective—one might even say discerning—writers and readers have been when it comes to their appetites for history.

Though the historical settings of contemporary American fiction are as diverse as the authors who create them, a significant portion of this work falls within a highly specific constellation of historical subgenres: contemporary narratives of slavery, Holocaust fiction and the World War II novel, the multigenerational family saga, narratives of immigration, and the novel of recent history.

Testifying to the prominence of these individual subgenres, many notable novels in the last decade have fallen under the rubric of not one, but two or more of them. Ruth Ozeki’s A Tale for the Time Being, for example, chronicles the history of Japanese airmen during World War II, as well as the 2011 Fukushima nuclear disaster. Yaa Gyasi’s Homegoing is a multigenerational novel that narrates two halves of a family tree divided by enslavement, but reunited by way of immigration two centuries later. Margaret Wilkerson Sexton’s A Kind of Freedom is a World War II novel, a multigenerational family saga, and a novel of recent history that follows three generations of a Black family living in New Orleans from the 1940s, through the 1980s, to the period just after Hurricane Katrina.

Though it may seem odd to categorize works as various as Colson Whitehead’s The Underground Railroad, Min Jin Lee’s Pachinko, and Jesmyn Ward’s Salvage the Bones under the single heading of historical fiction, this broader approach enables us to recognize the larger literary ecosystem that allows those diverse forms to flourish: Taken together, they represent a sea change in conceptions of literary prestige, and a shift in value from narratives of the way we live now to chronicles in which—to borrow from Morrison—“nothing ever dies.”

This transformation of the American literary field has been, in many ways, a salutary one. It has led to a dazzling wealth of historical narratives, fostered the careers of a new generation of American writers, and contributed to the formation of a literary canon that is markedly more inclusive than it has ever been. More important still, it has helped to reshape American historical consciousness. As historians such as Hayden White have recognized for at least half a century, our understanding of the historical past is inseparable from the structure of the stories we tell about it. The long-refuted assumption that “the difference between ‘history’ and ‘fiction’ resides in the fact that the historian ‘finds’ his stories, whereas the fiction writer ‘invents’ his,” White argues, overlooks both the historian’s commitment to narrative tropes and the historical novelist’s commitment to factual research.

As the writers just mentioned have demonstrated well, fiction is a powerful tool for producing historical knowledge. Historical fiction shapes our collective memory, personifies key events and periods, reveals the deeper roots of contemporary crises, unsettles neat chronologies, challenges the historical record, exposes its lies and lacunae, recovers disregarded stories, and conjures others to stand in for those that have been lost entirely. Indeed, by stimulating a critical encounter with the past, historical fiction, at its best, turns its reader into a kind of time traveler.

We are living in a golden age of historical fiction, but also a period in which the understanding it promotes is being increasingly policed. The culture and canon wars of the 1980s and 1990s not only helped to bring about American literature’s focus on the past; they also offered a kind of prologue to today’s cultural politics, where ferocious debates over which books are taught, and how, have not only resurfaced but intensified. The political proxy wars that once focused largely on university English departments have now spread to new and alarming fronts, from the public library to the high school classroom. Many of the novels discussed here—Morrison’s in particular—have already been targeted by right-wing pundits, banned by local school boards, and outlawed by state legislators. I have little doubt that more will follow.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →At the same time, the sustained assault on narratives of history also emphasizes the limits of what those narratives can accomplish on their own. It may be comforting to imagine that these efforts to stymie literary culture and sanitize the historical record will someday be judged harshly by history. But that way of thinking only highlights how thoroughly historical fiction’s backward glance has come to frame contemporary politics. Understanding the past is a necessary but ultimately insufficient condition for effecting change in the present.

Over the last five decades, a number of literary institutions have inadvertently encouraged the belief that history can act as the central staging ground for issues of contemporary injustice and inequality. The Pulitzer Prize and its peers have elevated novels about the 1920s that offer comparisons with today’s ultra-rich, and stories of the ’60s that allude to today’s over-policed, but neither address the present with the unflinching gaze our moment requires. Given fiction’s extraordinary capacity to resuscitate the past, these institutions have at times mistaken historical recovery for a form of historical redress.

Thirty years ago, Toni Morrison argued in Playing in the Dark that the American literary canon had assisted in “the construction of a history and a context for whites by positing history-lessness and context-lessness for blacks.” In the decades since then, a generation of Black, Asian American, Latinx, and Indigenous writers has marshaled historical fiction as a means of rectifying this disparity, and a range of cultural organizations have consecrated those writers for doing so.

It is certainly not lost on historical novelists—or their readers—that historical fiction is always to some extent about the time in which it is written rather than set. Yet in recent years, writers have worked to highlight the limits of the easy analogy between past and present, as well as how it has become an expectation placed upon minoritized writers in particular. Take the narrator of Nguyen’s The Sympathizer, for example, whose stories of the Vietnam War and its aftermath are the product of interrogation and forced confession. As Nguyen writes in the opening lines of the novel, “I wonder if what I have should even be called talent. After all, a talent is something you use, not something that uses you. The talent you cannot not use, the talent that possesses you—that is a hazard, I must confess.”

Or consider Cora, the protagonist of Whitehead’s The Underground Railroad, who escapes enslavement only to find that the sole employment available to her is playing an enslaved woman in a white-owned museum. As that novel makes clear, when the only job in town is historical reenactment, representing the past can seem more like a trap than a means of getting free. As this year’s prize lists will surely attest, in the world of American literature, the past isn’t dead—it isn’t even past.

More from The Nation

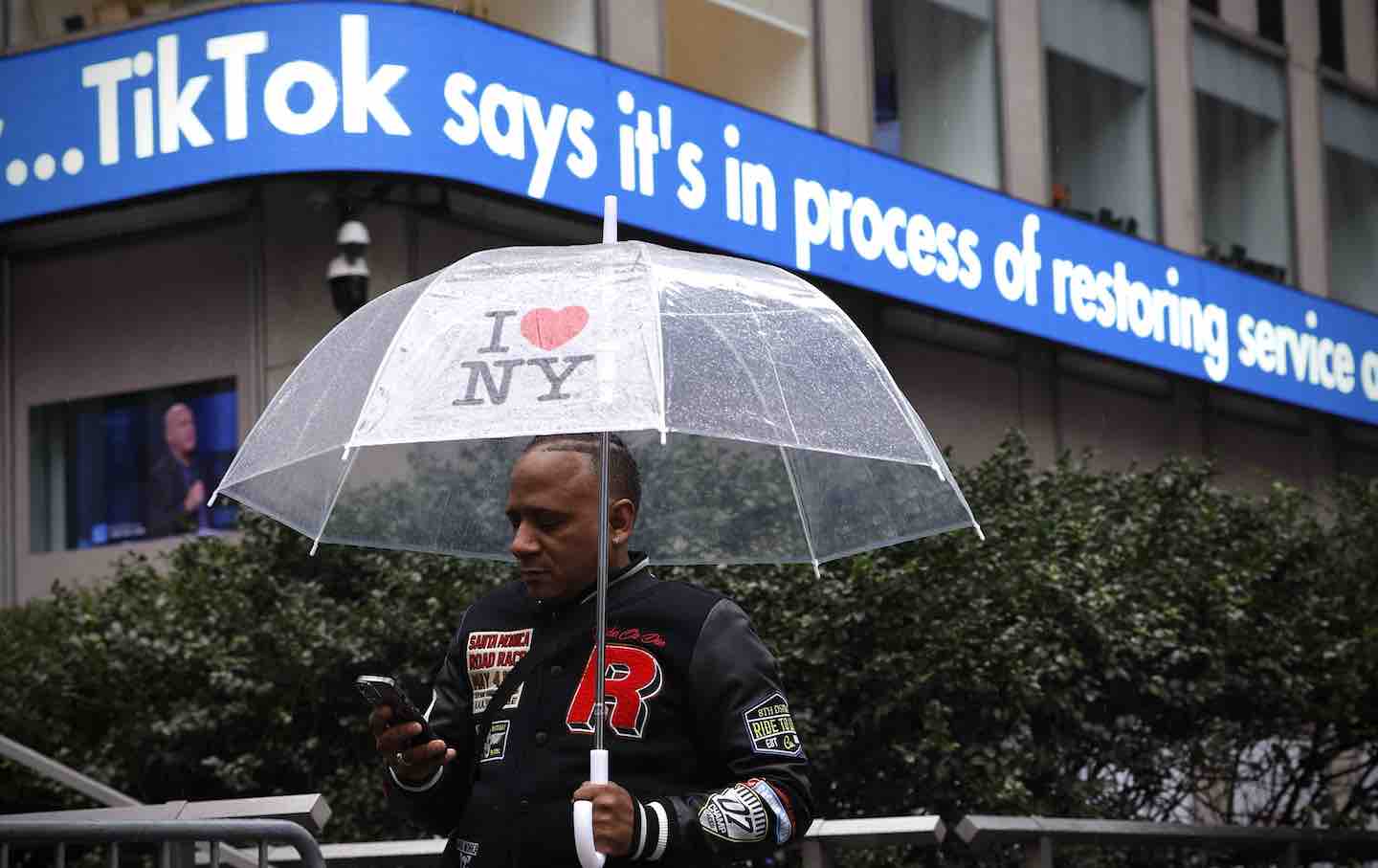

TikTok’s Incomplete Story TikTok’s Incomplete Story

The company has transformed the very nature of social media, and in the process it has mutated as well—from tech unicorn to geopolitical chesspiece.

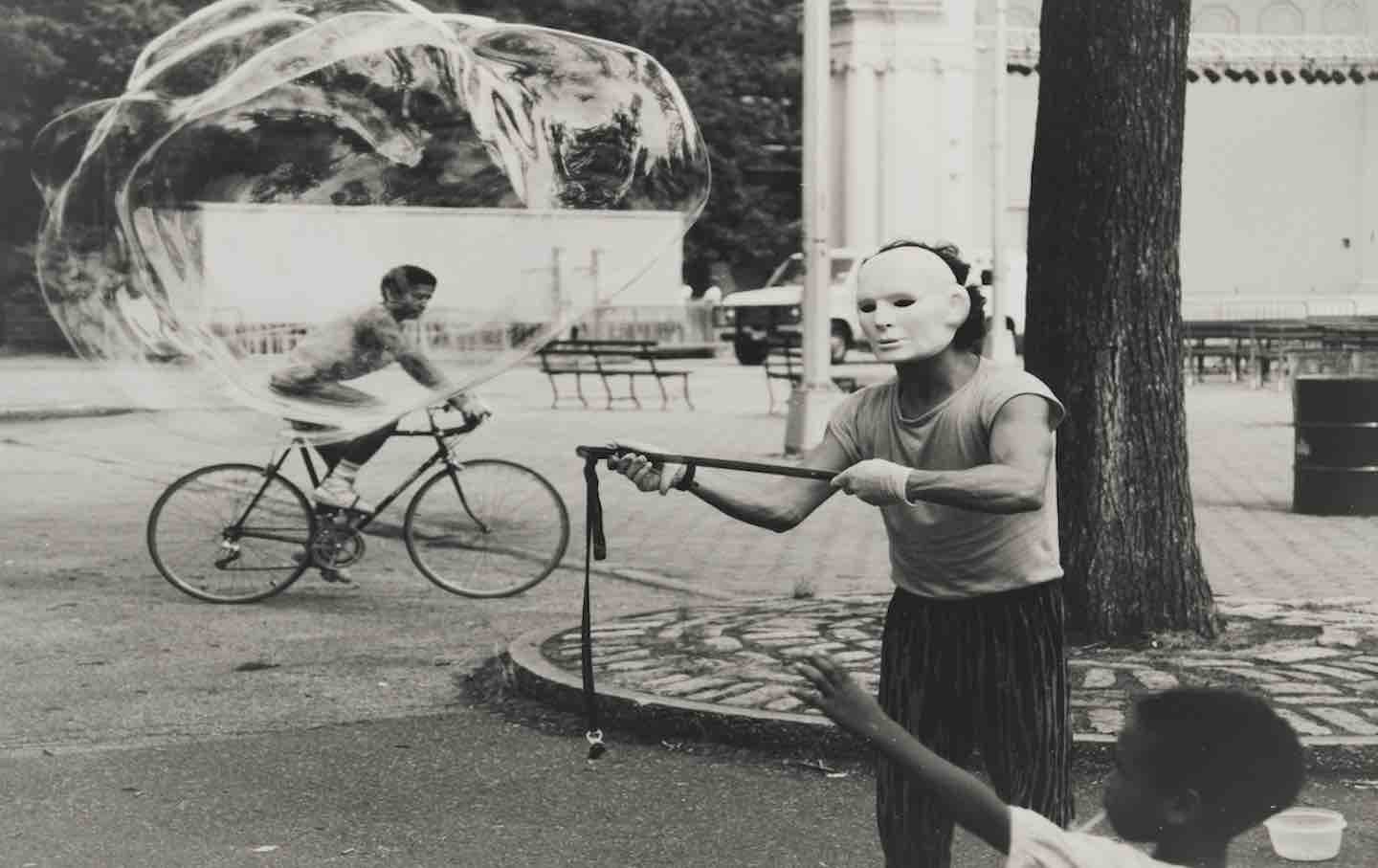

Did We Get the History of Modern American Art Wrong? Did We Get the History of Modern American Art Wrong?

The standard story of 1960s arts is one of Abstract Expressionism leading into Pop Art and minimalism. A Whitney show proposes an altogether different one centered on surrealism.

The Bleak History of the American Work Ethic The Bleak History of the American Work Ethic

In Make Your Own Job, Erik Baker shows just how long Americans have scrambled to pile work on top of work—and at what cost.

The Banal Spectacle of “Avatar: Fire and Ash” The Banal Spectacle of “Avatar: Fire and Ash”

Has James Cameron’s epic sci-fi series run aground?

The Dislocations of Shuang Xuetao The Dislocations of Shuang Xuetao

The Chinese writer’s fiction details how the country transformed on an intimate level after the Cultural Revolution.

An Absurdist Novel That Tries to Make Sense of the Ukraine War An Absurdist Novel That Tries to Make Sense of the Ukraine War

Maria Reva’s Endling is at once a postmodern caper and an autobiographical work that explores how ordinary people navigate a catastrophe.