The Education Factory

By looking at the labor history of academia, you can see the roots of a crisis in higher education that has been decades in the making.

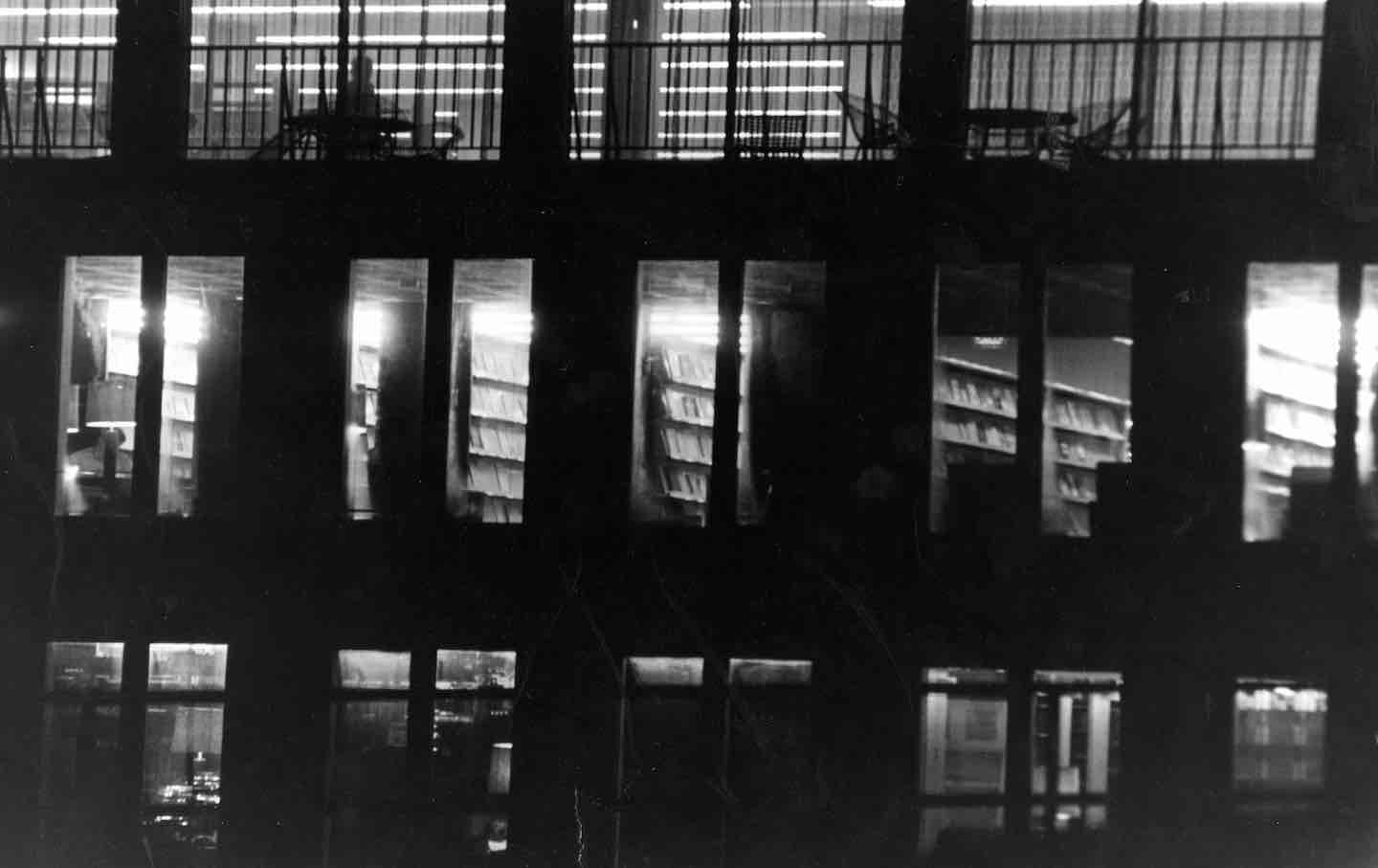

At nighttime, the levels inside the Milton S. Eisenhower Library light up the windows, showing stacks of books and the silhouettes of students working at tables and lounging at chairs, from A Level to B Level and M Level at the top, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, Maryland, 1965.

(Photo by JHU Sheridan Libraries / Gado / Getty Images)A week before I started my first job as a non-tenure-track contingent faculty member, I found myself in a basement auditorium listening to a university administrator expound upon the transformation of higher education in our century. In an increasingly competitive and fast-paced marketplace, he explained, manufacturers had discovered the need to transition from a “just-in-case” model of production, amassing stockpiles to respond to unexpected surges in consumer demand, to a “just-in-time” model, where sophisticated information technology allowed them to save money on labor and equipment by adjusting output to demand in real time. He paused, letting us ponder what the point of this wonky excursus into business history might be. Then the reveal: The story was about us. Whether a corporation made widgets or forged young professionals, the just-in-time model was the only way of doing business. We used to be able to get away with treating our students’ minds like Fordist warehouses, stuffing them full of knowledge that they might never have cause to use. But times had changed. Now we needed to figure out exactly what the market was demanding they know and teach it to them—no more and no less.

Books in review

Contingent Faculty and the Remaking of Higher Education: A Labor History

Buy this bookTaking this all in, I thought about the first time I came to this campus basement. It was my second year of graduate school at the same university. I’d been invited to a union organizing training, which took place in the room next to the auditorium where I was now sitting for new faculty orientation. The previous fall, the nascent grad student union had narrowly lost an election with the National Labor Relations Board, a result the union was challenging on legal grounds due to some alleged malfeasance by the university. There were rumors that a decision would be coming soon, and that the most likely outcome would be a new election. I’d done some get-out-the-vote work in my department during the first election, but not much more than that. I was determined that if we got a second chance, I’d do my part. I think a lot of people felt that way, and when the NLRB ordered a second election, we mustered a much stronger showing.

It seemed for a moment that I could hear the voices from that first training echoing through the walls. I wondered if the administrator sermonizing before us might not hear them too, a specter haunting his homily on market discipline. What went unspoken that morning was that many of us sitting there were just-in-time employees, not merely just-in-time educators. We were hired on a short-term basis, ostensibly to fill short-term needs (even though many contingent faculty members teach introductory or mandatory courses that must be taught each year). We didn’t know, in many cases, if we’d still have our job in a year’s time. We all knew, however, that without a doubt we’d be laid off (“nonrenewed”) at some point, regardless of our performance, because of the university’s insistence on capping the length of time that individuals were allowed to hold most non-tenure-track faculty appointments. The university had no desire to accrue any stockpiles.

This system, as the labor scholars Eric Fure-Slocum and Claire Goldstene show in their new volume Contingent Faculty and the Remaking of Higher Education, is hurtling headlong into crisis. Contingent faculty have no choice but to discover how to wield the power in our ever-increasing numbers. By one estimate, close to three-quarters of teaching staff in US colleges and universities are now employed on a contingent basis—on one-year, one-semester, or even one-course contracts, often working “part-time,” without benefits, toiling at multiple institutions simultaneously in order to afford rent. In the 1970s, about three-quarters of postsecondary teachers worked on the tenure track, and a greater proportion of contingent instructors had full-time professional employment and taught for supplemental income or for the intrinsic rewards of teaching. The professoriate was proletarianized in the span of a generation. It was an explosion of precarity and exploitation. And now the fallout is here: a battle between the corporate university and the contingent faculty majority for the future of higher education.

What happened? The explanation I hear most often, on those occasions when the taboo against open discussion of “adjunctification” is breached, is budget shortfalls: Universities today, the story goes, just can’t afford to spend as lavishly on faculty as they once did. This excuse often originates in the university’s administrative C-suite (among deans, provosts, and the presidents) and then is propagated dutifully down the ranks, sometimes accompanied by half-hearted lectures on neoliberalism and the Long Downturn and the end of the Cold War university. The essays in the first part of Contingent Faculty and the Remaking of Higher Education obliterate this mythology. Sue Doe and Steven Shulman, scholars at Colorado State University, present especially revelatory data. Rather than being imposed on administrators by revenue shortfalls, Doe and Shulman show, faculty casualization is driven by the quest to maximize what they call “instructional surplus,” the amount of money a school rakes in from each student minus what they spend to educate them. The schools that rely most heavily on contingent faculty are not those that are struggling to afford to educate students (such schools are few and far between, Doe and Shulman find) but those that are banking the most money per student. Adjunctification, then, is the byproduct of a financial equation: a tool to wedge open the divide between how much a school spends on education and how much it earns per student in tuition, fees, and government subsidies. American higher education demolished the tenure track not in order to make ends meet but in order to amass profits. (Explicitly for-profit schools, as Doe and Shulman observe, have all-contingent faculties.)

The question of faculty casualization, in short, is the question of how American colleges and universities transformed into profit-hungry corporations masquerading as educational nonprofits. Part of the answer, as the historian Elizabeth Tandy Shermer argues in her contribution to the collection, is that this transformation really represents a reversion to the historical norm after a brief and decidedly incomplete mid-20th-century interruption. When postsecondary schools were built, in the 18th and 19th centuries, they relied on land and wealth extracted through slavery and Indigenous genocide; Gilded Age robber barons transformed universities into R&D labs and workforce training centers. Faculty labor organizing, inspired by New Deal–era union activism, ultimately forced schools to improve job security and working conditions, including by implementing the modern tenure system—but the “golden age” was always an uneasy compromise.

The collapse of this compromise occurred gradually and at first imperceptibly. There was no epochal shift in administrative consciousness, just a series of smaller dislocations that changed the calculus about the rationality of the tenure settlement. Changes in the funding landscape did play a role here, as a variety of contributors show. Reductions in government expenditures prompted by stagflation in the 1970s fostered a cost-cutting sensibility across higher education. An increasingly “nontraditional” student body, enrolled part-time or as their personal finances would permit, created unpredictable fluctuations in tuition revenues that also prompted austerity. The expansion of the student loan industry allowed schools to jack up tuition prices, but the consequence was a competition to prove to prospective customers that the “student experience” was worth their investment—hence the drive to maximize profits that could be diverted to fund state-of-the-art dorms, gyms, stadiums, and other campus amenities.

The essays in Contingent Faculty and the Remaking of Higher Education also underscore the fact that the more diverse scholars who entered the professoriate in increasing numbers in the late 20th century were, politically speaking, easier to exploit than their predominantly rich-white-man predecessors. Women and people of color were often the first faculty members to find their positions casualized, and they remain disproportionately represented in the adjunct ranks today.

Not only did adjunctification allow schools to cut costs at the expense of their most disempowered teachers, but it also helped higher education weather the campus radicalism of the 1960s and early 1970s, as the scholars and labor activists Joe Berry and Helena Worthen illustrate. Precarious workers are easier to discipline and to discharge. When student demands prompted schools to create new programs in ethnic studies, gender studies, and labor studies, administrations decided to staff these institutions—magnets for subversive types—overwhelmingly with contingent faculty.

Despite their precarity, however, contingent faculty are turning out to be less docile than administrators might have hoped. Freedom’s just another word for nothing left to lose, and as Contingent Faculty and the Remaking of Higher Education shows, that’s where many proletarianized academics find themselves. There are the daily humiliations: course materials stored in car trunks, office hours held at a local Starbucks, 14-hour days stuffed full of “part-time” teaching, the metastasizing credit card debt. There is the inability to plan one’s life, the ceaseless uprooting and peregrination. The absence of time: to research, to write, to keep one’s courses up to date. The professional insults, the slights both thoughtless and deliberate, exclusion from whatever modicum of faculty governance today’s schools still retain. Above all, the worry: ineradicable, asphyxiating.

So it’s no wonder that contingent faculty and other academic workers are fighting back. The Coalition of Contingent Academic Labor was founded in 1996 to coordinate contingent labor activism across North America; the New Faculty Majority followed in 2009, and Higher Ed Labor United in 2021. Big unions like the Service Employees International Union, the United Auto Workers, and the American Federation of Teachers have augmented the efforts of these coalitions with organizing on campuses around the country, in both the private and public sectors. Academic workers, especially graduate students, have been winning union elections at a remarkable clip lately, frequently recording margins of victory well over 90 percent. In the worst depths of the pandemic, as a variety of contributors document, unions played an indispensable role in combating layoffs and fought to secure safe working conditions.

In a sign of the times, The Chronicle of Higher Education now sells a report titled “The Unionized Campus” that administrators can purchase to learn “how to coexist with academic labor unions.” Some of them, it seems, are listening. The same university that ran such a vicious anti-union campaign when I was in grad school more or less declined to contest our new union for non-tenure-track faculty and researchers when we undertook an NLRB election earlier this month. I’m sure they suspected that mounting an oppositional campaign wouldn’t be worth the effort, and with 93 percent of voters supporting the union, we proved them right.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →But it’s still not enough. A series of sobering essays that conclude Contingent Faculty and the Remaking of Higher Education seek to explain why, as the labor historian Trevor Griffey puts it, “faculty labor organizing has so far produced limited and often unsatisfying results for its non-tenure-track members.” The byzantine complexity of American labor law is partly to blame. In the private sector, the status of many academic workers under the Wagner Act is unclear and ruled by the ever-changing whims of the NLRB. The board judged tenure-track faculty to be too managerial to merit union representation in 1980, in NLRB v. Yeshiva University. Graduate students and non-tenure-track faculty, on the other hand, are union-eligible—although there has been much flip-flopping on the question of graduate students over the years, and many of us spent the Trump years praying that his right-wing board wouldn’t move to exclude them once again.

Meanwhile, public-sector labor law varies significantly from state to state. Tenure-track faculty at public schools, unlike their private-sector counterparts, tend to be union-eligible, so there are many unions that include both contingent and tenure-track faculty. Such wall-to-wall faculty unions wield more strike power, but contingent faculty sometimes struggle to ensure that their interests are adequately prioritized. In both the public and the private sectors, tenure-track and senior faculty do not always demonstrate solidarity with their contingent colleagues, and some do worse than that. One of the biggest obstacles to academic labor organizing is the industry’s insidious meritocratic culture, the widespread assumption that people who get trapped teaching off the tenure track are victims of their own intellectual or professional inadequacy. Academics who derive their self-worth from their relatively superior status have a hard time supporting the labor movement’s challenge to professional hierarchy.

In many respects, contingent academics confront the same obstacles that bedevil labor organizing among precarious and casualized workers elsewhere in the economy. The high turnover that comes with short-term contracts can wipe out organizing committees without management having to lift a finger. The threat of retaliation is more palpable for workers who toil without even a pretense of job security. And if you’re constantly driving all over your metro area to four different jobs trying to pay the bills, it’s hard to find the time to devote to building or sustaining a union effort at any given workplace. As the contributors to Contingent Faculty and the Remaking of Higher Education emphasize, the casualization of academic labor is just one manifestation of the same underlying dynamics that have driven the emergence of a “precariat” in nearly every industry. We’re in the same gig-economy boat as everyone else.

Looking back on it, I realize there was a great deal of truth in what that administrator had to say to us that day, on the eve of my own entry into the academic precariat. The old model of academic research and teaching is gone for good. Whatever walls we may have imagined sequestering the academy of the past from the pressures of the “real world” have clearly eroded, if indeed they ever existed in the first place. But if university administrators find themselves ever more closely entangled with capital, restructuring their campuses to serve the just-in-time demands of markets for labor and knowledge, those of us on the front lines of scholarship and education have the opportunity instead to embrace the demands made on us by mass movements for social and economic justice. Devoid of the expectation of professional comfort, we may find ourselves able to listen more closely to the Rilkean message that it is the vocation of labor organizers and intellectuals alike to deliver: You must change your life.

More from The Nation

The Peculiar Case of Ignatius Donnelly The Peculiar Case of Ignatius Donnelly

The Minnesota politician presents a riddle for historians. He was a beloved populist but also a crackpot conspiracist. Were his politics tainted by his strange beliefs?

The Agony of Aaron Rodgers The Agony of Aaron Rodgers

Is he the world’s most interesting athlete or is he just a washed-up crackpot?

Can You Understand Ireland Through One Family’s Terrible Secret? Can You Understand Ireland Through One Family’s Terrible Secret?

In Missing Persons, Clair Wills's intimate story of institutionalized Irish women and children, shows how a family's history and a nation’s history run in parallel.

Peter Schjeldahl’s Pleasure Principle Peter Schjeldahl’s Pleasure Principle

His art criticism fixated on the narcissism of the entire enterprise. But over six decades, his work proved that a critic could be an artist too.

How the Western Literary Canon Made the World Worse How the Western Literary Canon Made the World Worse

A talk with Dionne Brand about her recent book, Salvage, which looks at how the classic texts of Anglo-American fiction helped abet the crimes of capitalism, colonialism, and more...

Along the Roads That Built Modern Brazil Along the Roads That Built Modern Brazil

José Henrique Bortoluci's What Is Mine tells the story of his country’s laborers, like his father, who built its infrastructure, and in turn its fractious politics.