Guy Davenport—the Last High Modernist

In the essays collected in Geography of the Imagination, one can glimpse the inner workings of the mind of a 20th-century literary genius.

Whitman appearing at Poe’s funeral, toward the back. A young Picasso catching a glimpse of the prehistoric bull paintings at Altamira. Allen Ginsberg, mid-chant at Charles Olson’s funeral, accidentally pressing the pedal to lower the coffin, leaving Olson’s remains “wedged neither in nor out of the grave.” Whittaker Chambers sponsoring Louis Zukofsky’s Communist Party membership bid. Kafka observing an air show as the first pilots took flight. Emerson expressing his dismay at the dinner-table talk of Thoreau and Louis Aggasiz on the sexual habits of turtles.

Books in review

The Geography of the Imagination: Forty Essays

Buy this bookThese are among the meetings of the minds gathered together in Guy Davenport’s masterpiece The Geography of the Imagination, a wide-ranging collection of essays that fuses together the multifaceted author’s long engagements with his cultural ancestors. The fruits of serious time spent reading, Davenport’s gift is a kind of literary eros: His affinity for these artists is so great that, even as he brilliantly analyzes their texts, he can’t help but try to conjure them to life. Scholar, critic, and artist rolled into one, Davenport was the standard-bearer for a variety of serious belles lettres, the likes of which is rare today—who now has done so much homework? Returned to print with a new introduction by John Jeremiah Sullivan, Geography is a powerful reminder of the pleasures of erudition, and perhaps a barometer of today’s literary culture and its diminished capacity for difficulty.

For Davenport, the literary anecdote mattered; he recognized it as the “last survivor of an oral tradition.” And it was part of how his mind moved: Revolutionary ideas were embodied by great men (and, tellingly, less often women)—heroes of the past who came into contact, often fleetingly, and exchanged their genius. In his view, the flowering of culture is the product of these meetings rippling through history. Davenport himself was no stranger to these anecdotal encounters—he seems to have met a fair number of his artistic gods.

Here are some of the stories he sorts through: stumbling upon Ezra Pound’s original blueprint for The Cantos while helping the aged, mad poet move into a new apartment in Rapallo; a coffee chat with Samuel Beckett; attending boring Oxford classes taught by J.R.R. Tolkien; lunching in Kentucky with the photographer Ralph Eugene Meatyard, the monk and writer Thomas Merton (“in mufti, dressed as a tobacco farmer with a tonsure”), and “an editor of Fortune who had wrecked his Hertz car coming from the airport and was covered in spattered blood from head to toe.” He reports that the restaurant treated them with impeccable manners. Perhaps more importantly, these morsels of storytelling lend Davenport’s formidable learning a voice, one with charm and humility, even a kind of boyishness (hero worship is always at hand). Moreover, they stitch together his unconventional leaps of logic and arcane references, grounding the reader even when the path of the essay may be unfamiliar.

The pleasure of reading Davenport is not just in spending time with someone who has read more widely and deeply than you have—though it’s that, too—but rather in his power of making surprising connections. The memorable lines that open the collection’s title essay propose to put all of culture, across all time, into some kind of relationship:

The difference between the Parthenon and the World Trade Center, between a French wine glass and a German beer mug, between Bach and John Philip Sousa, between Sophocles and Shakespeare, between a bicycle and a horse, though explicable by historical moment, necessity, and destiny, is before all a difference of imagination.

This assertion is, at its heart, a question of style: All cultures have buildings, beverages, music, theater, and modes of transportation, but the contrasts between them are central to how we understand ourselves and others. How these choices came to be, however, requires an investigation that can span centuries and vast distances. “Every force evolves a form,” taken from the Shakers and the seemingly inevitable simplicity of their art, is one of Davenport’s most cherished phrases—even as artists choose, forces of nature always work upon those choices. Chance and circumstance are key, but Davenport still insists on that most elusive of qualities, the imagination, to explain the particulars: People dream, guess, and suppose (to paraphrase him slightly), and these intangible urges press up against their material conditions and lead to moments of creativity. Even if you grew up in a cornfield, you might still dream of the sea.

“The imagination; that is, the way we shape and use the world, indeed the way we see the world,” Davenport writes, “has geographical boundaries like islands, continents, and countries. These boundaries can be crossed.” The title essay labors to construct an elusive third option between cultural determinism (that you are inevitably a product of your origins) and a free-floating subjectivity (that we can escape our contexts entirely). Davenport’s sprawling project as an essayist, then, is to try to track those boundary crossings and detect influences that might have escaped our notice at first. The essay’s culmination is an extended close reading of Grant Wood’s American Gothic, drawing a map out of every item in the frame. The bamboo screen from China (“by way of Sears Roebuck”), the glass from Venice, the pose of the couple out of the whole history of portraiture—this most American of images was created by a global flow of ideas and materials. Davenport’s “geography” is a kind of spatial aid to the way we think about culture: The painting isn’t just one exhibit in a long gallery of “periods” that follow one after the other. Instead, it’s a demonstration of many traditions all intertwined on the same canvas. Like a map—if one knows how to read it. And taking it all in at once is how we might begin to understand how the boundaries blur.

Another pleasure of reading Davenport is in his roaming, in never knowing his exact destination. He is just as likely to resort to simile and metaphor (“The imagination is like the drunk man who lost his watch, and must get drunk again to find it”) or swerve into a subject that is completely fascinating but also somewhat unclear in exactly how it connects to his original point. On the way to American Gothic is an extended examination of Edgar Allan Poe’s tripartite imagination: grotesque, arabesque, and classical, in Davenport’s telling. The close reading itself is elaborate and entertaining enough to quell the reader’s doubts of how, exactly, everything will fit together. Onward, then, he leaps to the Goncourt brothers, Spengler, Joyce, and so on. With Davenport, the reader is always on a journey, and it can feel good to know that there is someone a few steps ahead of you, guiding the way even if you’re temporarily lost.

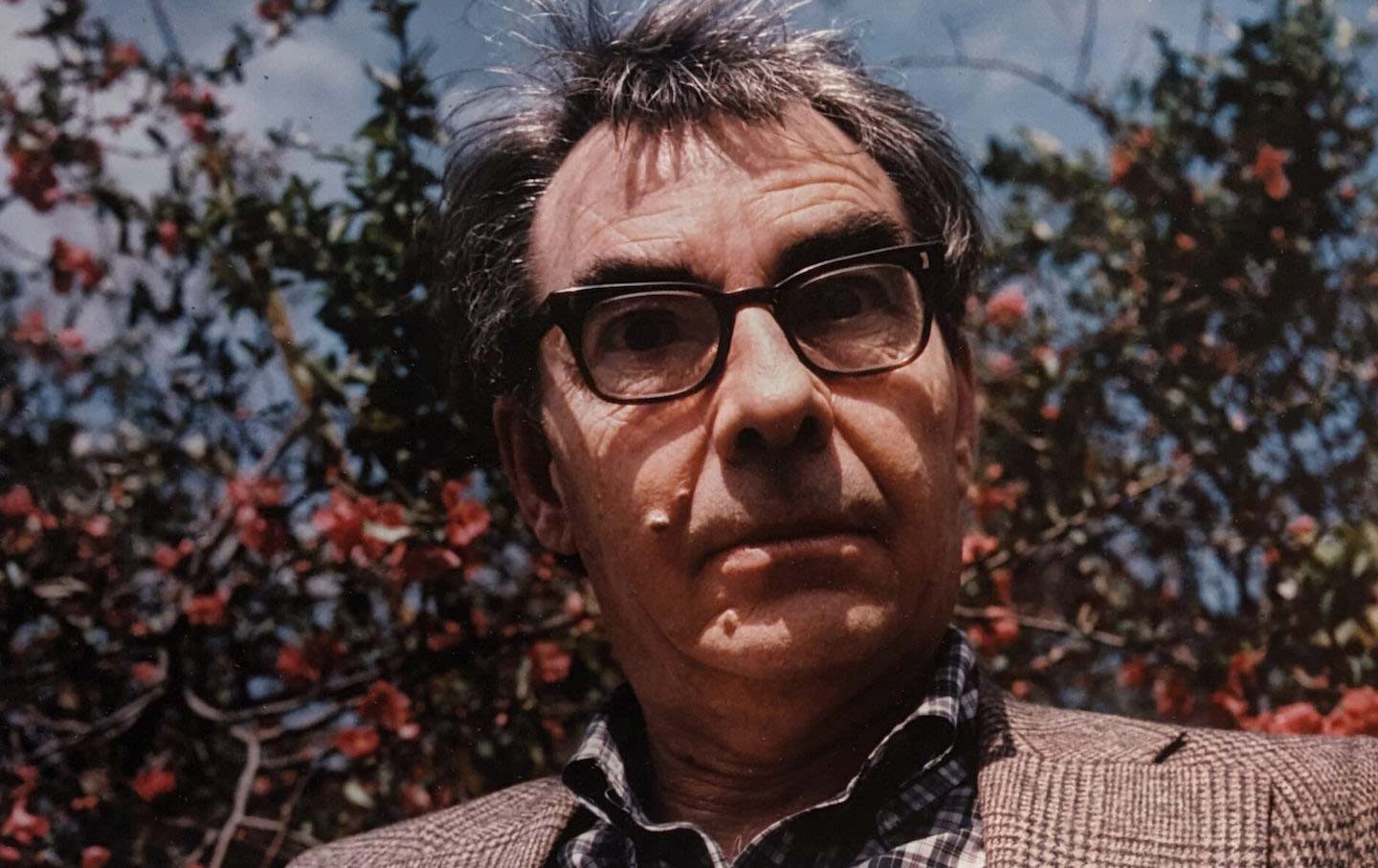

Peripatetic as his writing was, Davenport was, by his own admission, someone who hated travel. He was born in South Carolina in 1927, and his Southern roots occasionally surface when his writing dips into the personal (particularly memorable is his story of being taken to his Black nurse’s house to eat clay in order to cure his indigestion). The majority of his life took place in the university: Duke, Oxford, Harvard, and eventually a post at the University of Kentucky. “The farthest away for the highest pay,” he is reported to have said. There were brief interruptions for travel as well as time spent in the US Army during the Korean War—his main memory of the latter seems to be reading Thomas Mann’s Joseph and His Brothers in the Fort Bragg rec room. Davenport would teach at Kentucky for decades, although his attitude toward the experience seems to have been ambivalent at best—he considered teaching noble in the abstract, but in practice a futile chore. Meanwhile, he toiled away inside his immense library at his brilliant and often arcane writing.

After winning a MacArthur “genius grant” in 1990, Davenport retired to write full-time. Before his death from lung cancer at the age of 77 (he was a lifelong smoker), he was incredibly productive, with numerous volumes of essays, fiction, poetry, and translations of ancient Greek poets and philosophers to his name. He was also a painter and often an illustrator of his own work. In another essay collection, Davenport approvingly notes the wisdom of Montaigne in leaving the world of business and court intrigue to spend his days in peaceful, humanistic introspection. It’s not hard to see the older Davenport in this image: a gentleman squire, intellectually engaged but essentially aloof. He took pleasure in life outside his library, but his understanding came through the texts that structured his world.

At times, Davenport has the aura of “The Last Man Who Knew Everything,” the epithet once bestowed on the English polymath Thomas Young. However, a closer inspection shows that Davenport’s breadth of subjects, while impressive, has a focus. High modernism is his home, particularly in literature (Joyce for his master’s thesis, Pound for his PhD), though he writes compellingly about the visual arts as well. Around half of Geography’s essays are about, or at least significantly involve, poets: Poe, Whitman, Stevens, Moore, Olson, Zukofsky, and others more obscure (a fascinating essay on the lesser-known Ronald Johnson is one of the collection’s best). In general, he is more content to root around in the text—if it is complex enough, he will find food for thought. His essays often have no fixed thesis or argument to speak of, and some of his sprawling close readings are more convincing than others: While his dissection of Olson’s famously opaque “The Kingfishers” is genuinely illuminating, his theory of Ulysses as based, chapter by chapter, on an ancient Celtic alphabet is perhaps more technically impressive than it is useful. He has many touchstones, or hobby horses, that he returns to again and again: Leonardo da Vinci (one of the first books Davenport read as a child was the artist’s biography, an obsession that seems to have molded him for a lifetime), prehistoric cave painting, Dogon theology, the ancient Greeks, Fourier, Wittgenstein, and above all, those demigods of the earlier 20th century—Picasso, Joyce, and Pound.

If “imagination” is the key to Davenport’s thinking on culture, he did not mean it in the way that it is often invoked today: a disruptive idea that strikes like a bolt from the blue. Tradition was indispensable, even inescapable, in the act of creation, he believed. In one of the collection’s most famous essays, “The Symbol of the Archaic,” Davenport provides another axiom of his thought: namely, that modernism needed to look backward, deep into the past, to advance. “What is most modern in our time frequently turns out to be the most archaic,” Davenport writes. “The sculpture of Brancusi belongs to the art of the Cyclades in the ninth century B.C. Corbusier’s buildings in their Cubist phase look like the white clay houses of Anatolia and Malta.” If The Geography of the Imagination asks us to think spatially or cross-culturally, Davenport here asserts the power of the “midden” of history, what he sees as the 20th century’s reabsorption of the past to create new, more vital work: “Archaic art, then, was springtime art in any culture.”

This attitude is itself characteristically high modernist, and Davenport saw his own style as a kind of primitivism, perhaps more in the “naïve” spirit of self-taught artists like Balthus and Henri Rousseau—the claim is debatable, but perhaps can be chalked up to Davenport’s modesty. This insight, or tension, lies at the heart of Davenport’s peculiar aesthetic: Returning to the archaic is a source of art’s freshness, but it simultaneously requires a huge scholarly apparatus to fully unwind the connections. In effect, his role as one of modernism’s great interpreters came with a downside: Davenport’s own archaic impulse, his desire to make art visceral, was always at risk of being overwhelmed by his learning.

Davenport was, of course, more than an essayist. His large body of fiction—mostly stories—has its champions, such as Sullivan. It also has its moments, but to my ears his essayistic experiments in fiction lack the grace of his “nonfiction” voice. Given that he had no real skill with character or plot, Davenport’s layerings can feel overworked, top-heavy with the relay of information in baroque language. And his conceits (Kafka, again, at the air show, or Robert Walser’s early career as a butler), which summon the hero worship that is central to his thinking, feel more at home in the realm of criticism. In “The Critic as Artist,” an essay collected elsewhere that perhaps best articulates Davenport’s own strengths, he concludes with a rather surprising cliché by his standards: “Literature does not ever say anything. It shows. It makes us feel. It is, in the world’s language, as inarticulate as music and painting. It is critics who can tell us what they think it means.” Perhaps Davenport was simply too articulate to re-create the absorption that he believed was literature’s highest achievement. His essays, which show more of his personality (though he is ultimately not a “personal essayist”), accomplish far more.

As Sullivan puts it in his breezy, pleasingly personal introduction, Davenport saw himself as “somebody who was working at the end of a civilization or tradition.” For him, “Modernism had been a cultural summit, like the Athenian Golden Age,” and now we were living “in the radioactive ash-lands of whatever that involved.” Of course, emphasizing that you stand on the shoulders of giants can tend toward diminishment—because of his density and his allusions, it’s easy to think of Davenport as a “writer’s writer.” Nostalgia can bring out the crank in him, although the stance is characteristically charming. His greatest contemporary antipathy was for the automobile, which Davenport blamed for the ravaging of American cities and culture, a quite defensible and prescient position.

Although Davenport is undoubtedly encyclopedic in many ways, it’s also worth noting what he omits—the most noticeable absence is any trace of pop culture. So many essayists today who claim a unique style (particularly those who aspire to “creative” or “literary” nonfiction) often seem duty-bound to rope in contemporary culture—Taylor Swift, say, or the latest Internet ephemera. Today, the poptimism wars are over (or, to put it differently, the “unpacking” of cultural ephemera as seen in Barthes’s Mythologies simply became the dominant form of cultural analysis), and pop won. Writers, fearing their irrelevance, feel they must insist that they belong to the “now.” Not so for Davenport: He stays firmly entrenched in his books, looking for deeper and deeper symbols in his masters. Although Davenport’s era is long past, there’s something appealing, almost romantic, in how little he fears irrelevance. Instead, he asks you to give things time: You may not understand everything in a difficult text, but that is itself the extended pleasure of reading. There will always be something further to encounter, if you choose to go on.

Davenport’s imagination always returns to Pound, that ever-troublesome modernist founding father, and a paragon of the ambiguity and density that Davenport valued. Pound is mentioned in or the subject of 26 of the 40 essays in Geography. His extreme eclecticism is perhaps the master key to Davenport’s imagination, as Pound’s best-known work, The Cantos, operates by extensive, almost uncontrollable, analogy. Incredibly disparate references are juxtaposed—Dante and Woodrow Wilson, Confucius and Odysseus—attempting to force the reader into thinking about what their relationship might be. Davenport is Pound’s ideal reader, able to grasp the threads of connection where those less booked-up might simply throw up their hands in bewilderment (and maybe for good reason). Davenport is not particularly forthcoming on Pound’s antisemitism or fascism, eliding it as madness. A political reticence, or at least mildness, is obvious. Rarely does Davenport acknowledge the perils of over-reading a text—the conspiratorial germ in Pound, for instance, is neutralized by ignoring how it might spill over into life. Complexity can be its own kind of safety, too.

As a supercharged reader, Davenport always tries to make the most of the texts he loves. Another of Geography’s best essays is a fascinating but far-fetched dive into the work of Eudora Welty, reading her fiction largely through the myth of Persephone. The intention is to situate Welty as a major modernist in the mold of Pound or Joyce, giving deep symbolic readings of her major novels and stories. Davenport recounts elsewhere, somewhat bashfully, that Welty wrote him once to say that his interpretation did not at all conform with her own sense of her work. “Death of the author” pending, Davenport’s humility at recounting this exchange breathes warmth into the analysis. And perhaps there’s something to be grasped from this ever-deeper excavation: the unconscious patterns in art and literature that hum in the air around any enduring work.

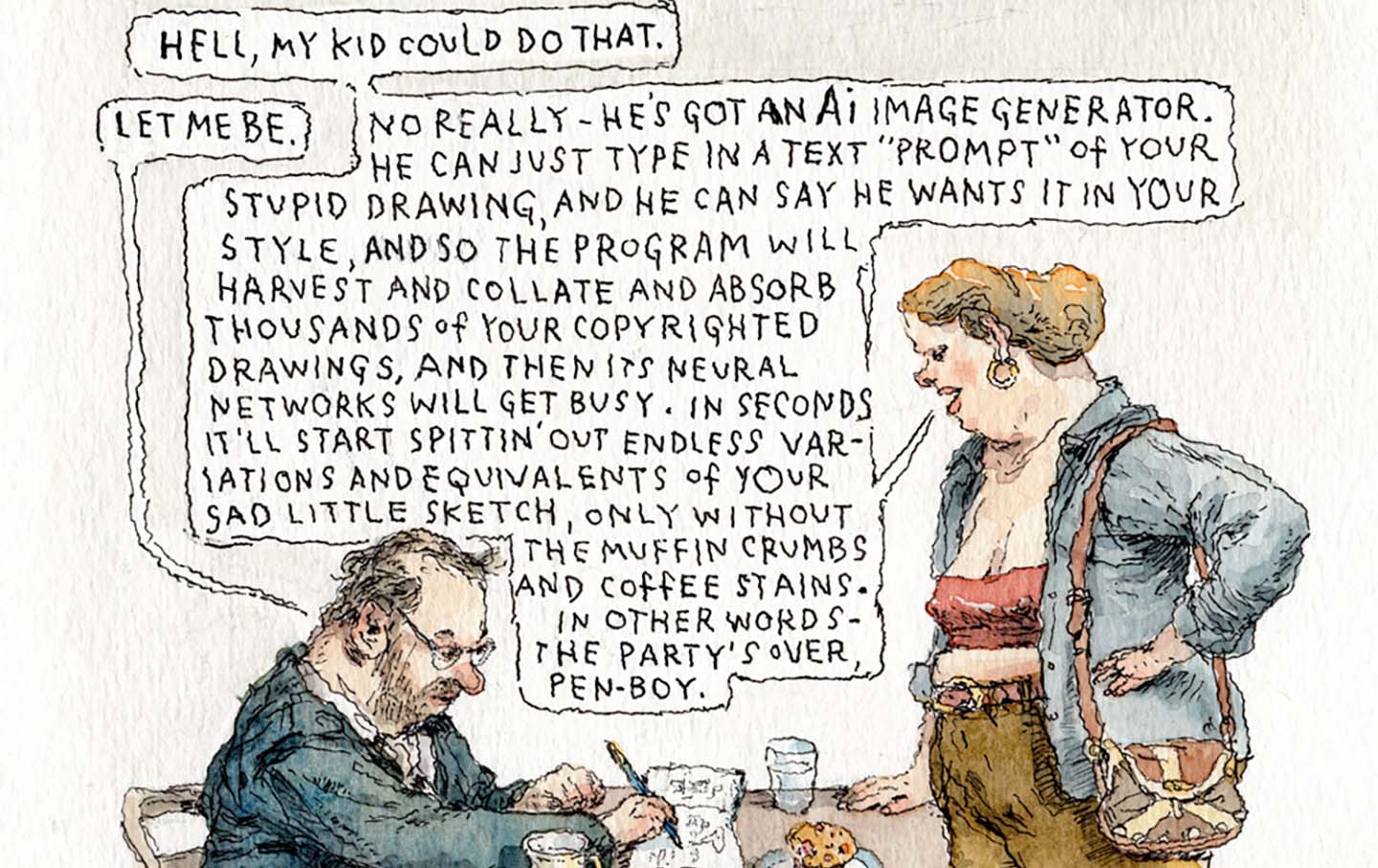

In the literary theorist Anna Kornbluh’s recent book Immediacy, Kornbluh writes about the dominance of a contemporary style that pretends to have no style at all: autofiction, streaming television, the low-friction churn of memes and social-media posts. In our hurry to move through the flow of stuff, we have become subject to a kind of art that feeds us “effortlessness” while depleting art’s essential power to make us stop and reflect. Davenport, in his labyrinths, his constraints, his obscure references, is the model of an artist who believes in dwelling with artworks. There is a density to his writing, a willingness to embrace the uncertain and to make us work a little harder to capture the meaning or the beauty of an image.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →His work feels salutary exactly because such ambitions are increasingly rare—modernism and its ambitions are receding from our culture, warts and all. At the same time, we experience a massive crush of information every day, a circumstance that more than ever requires a mind capable of describing, or inventing, relationships between the disparate works of art that populate the feed. Davenport asks us to practice invention in our associations, to not just settle for the catch-alls of “everything” and “all the time.”

Through the effort of thinking through those connections, even when they’re perplexing, a critic—or an artist—manages to make something from the information “midden” that might otherwise have been lost. As Davenport observes in “Finding,” one of the few purely autobiographical essays in the collection, “I learned from a whole childhood of looking in fields how the purpose of things ought perhaps to remain invisible, no more than half known. People who know exactly what they are doing seem to me to miss the vital part of any doing.” To take up Davenport, we should make haste slowly. Unhurriedness, distance, the eye unfocused at first: Through these patient arts, something rare might emerge.