Why Billionaires Are Obsessed With the Apocalypse

In Survival of the Richest, Douglas Rushkoff gets to the bottom of the tech oligarchy’s fixation on protecting themselves from the end times.

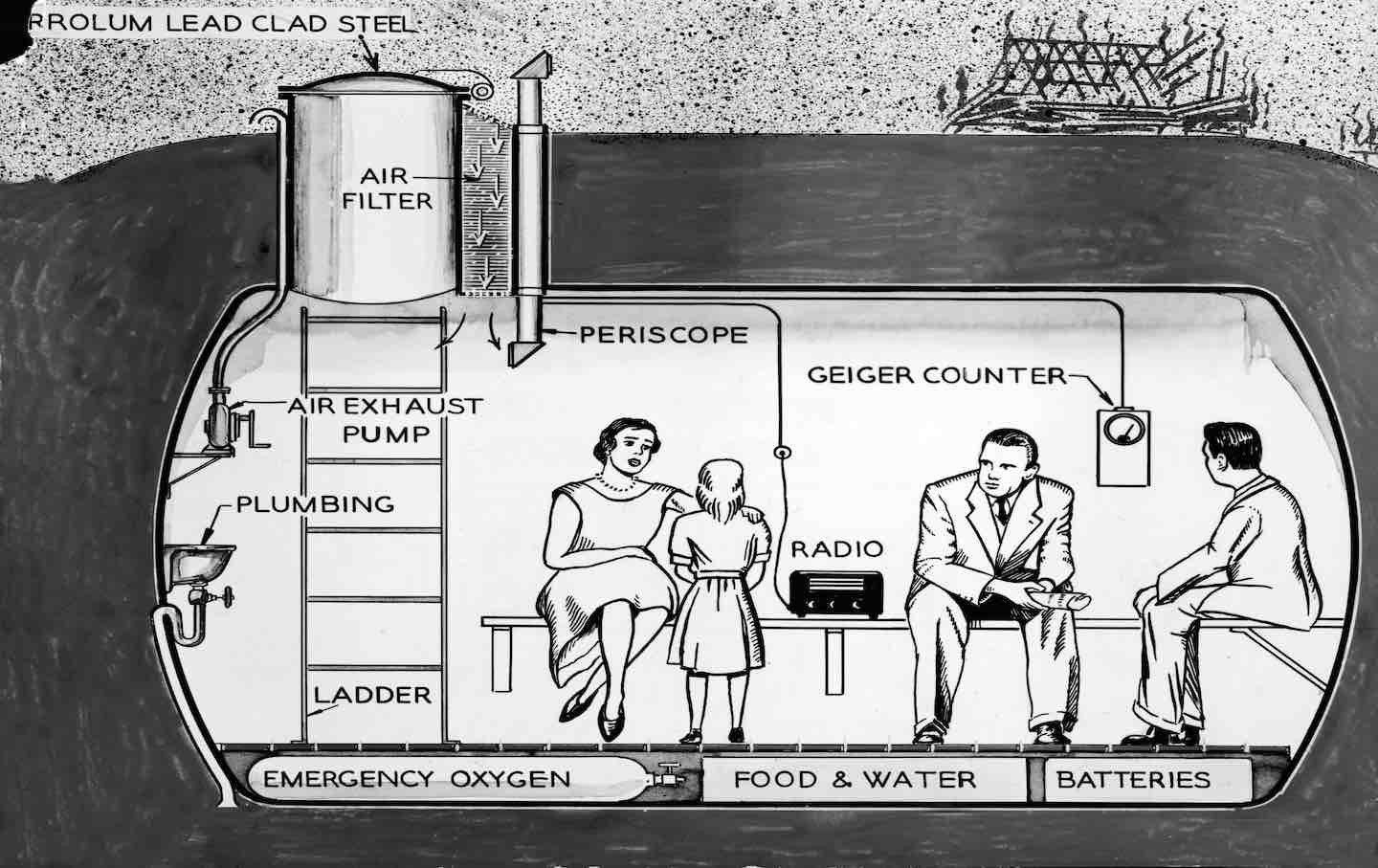

Cross-section illustration depicting a family in their underground lead fallout shelter, equipped with a geiger counter, periscope, air filter, etc., early 1960s.

(Photo by Pictorial Parade / Getty Images)At the opening of Survival of the Richest, Douglas Rushkoff is driven hours into the desert to a luxurious, secluded compound, where he meets a small group of billionaires with heavy investments in the tech sector. The men sit him down and, after a few preliminaries about crypto, AR, and VR, proceed to ask him which remote location would be the best place to build their doomsday shelters: New Zealand or Alaska? And if they hired armed guards to protect these compounds, how could they ensure their loyalty? (Would you, for example, withhold food from them, or make them wear disciplinary collars?) And most important, how could they insulate themselves from the people who would inevitably seek out their refuge? What these men were preparing themselves for was an unspecified cataclysm that they referred to simply as “the Event.”

Books in review

Survival of the Richest: Escape Fantasies of the Tech Billionaires

Buy this bookA self-professed humanist and Marxist media theorist, Rushkoff has long been a dissenting voice against the norms and mores of Silicon Valley. Having collaborated and been friends with the likes of Timothy Leary and Terence McKenna, Rushkoff was part of the psychedelic, cyberpunk subculture out of which the modern, user-facing Internet was born in the late 1980s and early ’90s. He has written a number of books, including Present Shock: When Everything Happens Now (2013), Throwing Rocks at the Google Bus (2016), and Team Human (2019). All of these works in some way seek to remind us of how the anarchic and communitarian spirit of early digital technology––the free sharing of information and ideas, the dreams of global consciousness, the “Gaia Hypothesis”––have all been corrupted by the power of big business. Given this record, it might seem strange that Rushkoff, of all people, would be summoned by a group of billionaires to answer questions about how to outlast a global disaster.

Rushkoff suspects that these men knew he would condemn their plans and wanted to see if they could withstand (and counter) his objections. It wasn’t so much about the technicalities or logistics, but rather the moral and metaphysical stress-testing they would have to undergo to see their plans through. J.C. Cole––one of the characters we meet early on in the book, a former president of the American Chamber of Commerce in Latvia and a Donald Trump devotee—tells Rushkoff on a tour of his Safe Haven Project, a postapocalyptic farming operation: “I am less concerned about gangs with guns than the woman at the end of the driveway holding a baby and asking for food.”

Apocalypse-proof real estate is now a lucrative and steadily growing industry, with companies like Vivos and Rising S offering luxury shelters for millions of dollars. The largest in the world is the Oppidum, located in the Czech Republic, about 50 kilometers outside of Prague. At 323,000 square feet, it was originally a military compound, presumably designed as a fallout shelter for high-ranking Communist Party officials in the event of a nuclear war. Construction began in the early ’80s, and in 2013 Czech entrepreneur Jakub Zamrazil created “The Oppidum project,” designed to transform it into a deluxe bunker that could be sold to the highest bidder. It includes both an aboveground estate (surrounded by high walls and motion-detection sensors) and an underground bunker that boasts luxury apartments complete with natural light simulators, wine cellars, gardens, art galleries, cinemas, and swimming pools, so that its owner can maintain a lavish style of life.

All of these men, Rushkoff writes, had succumbed to the fallacy that they can “earn enough money to insulate themselves from the reality they were creating by earning money in this way.” Rushkoff calls this (in one of his many coinages) the “Insulation Equation.” But this is merely a symptom of what he refers to as “the Mindset,” a mode of thinking that he sets off to explore after his strange encounter in the desert. The Mindset, broadly defined, is the tendency to see human interests as subservient to those of technological progress, or what the media theorist Neil Postman defined as “technopoly”: the “submission of all forms of cultural life to the sovereignty of technique and technology.”

The Mindset, Rushkoff argues, has its origins in the Enlightenment and the scientific revolution. It is based on the belief that human progress is a continuous and unstoppable upward curve and that there is no predicament (not even the end of the world) that we cannot innovate our way out of. It is an imperial mentality that demands perpetual extension, regarding everything on the planet as a potential resource, occasion for mastery, or opportunity for profit. Disregarding the laws of thermodynamics and exponential growth, the Mindset seeks the ultimate escape velocity.

Thus, we see why Elon Musk is obsessed with laying the groundwork for his extraplanetary colony; why Jeff Bezos wants to move heavy industry into orbit to keep the supply lines running if the planet is destroyed; why Mark Zuckerberg is trying to dial himself into his metaverse; or why Ray Kurzweil wants to upload his consciousness to a cloud. All of them are adherents of the Mindset; they believe that they can shield themselves from disaster and then remake the world to their liking. The future of technological progress, Rushkoff argues, is now an experimental endgame in which the wealthiest and most powerful race to find the escape hatch; it is less about raising up humanity than rising above the rest of us.

One might ask: What’s wrong with viewing technology as a problem solver? Or with developing solutions that can protect us from disaster? In principle, nothing. But as Rushkoff is careful to remind us, by appealing to the rich and exalting their inventions, we “perpetuate the myth that only a technocratic elite can possibly fix our problems,” which serves to “distract and discourage the rest of us from making substantive changes to the way we live.” Such an outlook has since become known (disdainfully) as techno-solutionism. Rushkoff points out that techno-solutions are all too often “informed by the values inherent in technology itself: exponential growth, automation over human intervention, forward momentum, platformization, and a disregard for existing conditions on the ground.” It also encourages a gamified vision of life: regarding the world as a kind of system that can be hacked or rebooted if we just grant those with the power to do so unlimited resources to carry out their plans.

Techno-solutions invariably reflect the traits of their proponents, which are more often than not speculative, fetishistic, antisocial, and ahistorical. They are also typically libertarian, eschewing any notion of collectivity or polity. Wishing to be free of oversight or accountability, the techno-solutionists harbor fantasies of unrestrained experimentation and self-sovereignty. One example of this is ReGen Villages, the product of James Ehrlich, a former game designer who teaches “disaster resilience” at Singularity University (which is not a university, in fact, but a company that acts as an “incubator” for entrepreneurs so they can “envision and master the future”). Although its website is littered with characteristically vague tech jargon and inspirational mission statements, ReGen promotes itself as harnessing machine learning for the creation of self-sustaining and resilient neighborhoods that can produce their own organic food, source their own water, and generate their own energy. The company also describes its proposed villages as the ideal place for educating children, raising people to have sustainable goals, and creating “healthy and secure communities in dynamically changing times.”

What this actually means in practice is anyone’s guess. What’s clear, however, is that the people who are likely to live in such settlements won’t be those most in need of things like clean-sourced water or sustainable infrastructure. As Rushkoff points out, “Rather than [help] an existing village or neighborhood utilize more regenerative principles,” the ReGen project seeks to buy up virgin land in order to start a new community from scratch. It appears to be little more than the fantasy of a former game designer, an attempt to make SimCity come to life.

Another example is the Seasteading Institute, the project of software engineer, economic theorist, and self-styled “anarcho-capitalist” Patri Friedman, the grandson of Milton Friedman, one of the godfathers of neoliberalism. Seasteading presents itself as an experimental micro-state and aquatic metropolis that “will allow the next generation of pioneers to peacefully test new ideas for how to live together.” Designed for “visionaries” and so-called “aquapreneurs,” it will provide the wealthy and powerful with “permanent, autonomous ocean communities to enable experimentation and innovation with diverse social, political, and legal systems.”

The cofounder of the Seasteading Institute is Peter Thiel, who is also currently attempting to develop remote property in New Zealand with the hope of establishing a haven for a “cognitive elite” of “sovereign individuals” (clearly inspired by Ayn Rand’s Atlas Shrugged). As Rushkoff points out, these entrepreneurs have always regarded the public and civic sectors as “antagonistic to their grand designs.” The creators of projects like ReGen and Seasteading have no interest in sustainable living or alleviating economic inequality. What they want is their own personal sandbox, unrestrained by governments, judicial oversight, or the collective will. These start-up societies reflect, if nothing else, a desire to create a new world from scratch and then choose who gets to be a part of it.

For adherents of the Mindset, every crisis is a potential business opportunity. Rushkoff cites TED Talks as a prime example of this. The formula of a TED Talk is as follows: identify a problem, reframe it to get people to see the problem in a whole new way, develop a business plan that can scale, then deliver a short speech that inspires enough venture capitalists to invest in the idea. Platforms like TED serve to give venture capitalism its philanthropic veneer, in which the kinds of problems that demand collective action and coordination—such as education reform, world hunger, climate change, and urban development—can be referred upward to an entrepreneurial elite whose members want to believe that their investments are a way of making the world a better place.

Rushkoff notes how these projects have a way of undermining public and state initiatives by “divert[ing] limited funding to moonshot boondoggles—all while making the wealthiest even wealthier.” For example, Singularity University has the XPRIZE competition, which offers as much as $100 million to the next great business idea that has the potential to “make a positive impact at planetary scale.” These proposals often come in the form of novel and totalizing solutions, or “game changers.” One of the traits of techno–solutionism, as Rushkoff rightly notes, is that it must necessarily reinvent the way we think about the problem in question. So rather than attempt to collectively reduce the possibility of extinction here on Earth, for instance, the answer becomes to leave Earth altogether. By extension, this outlook assumes that people can only be expected to act in their own interests if there are profitable incentives dangled before them, and any solution that is not lucrative should not be considered realistic.

This is the underlying logic of the “Great Reset,” a campaign started by Klaus Schwab, founder and chairman of the World Economic Forum. The Great Reset Initiative was launched during the Covid-19 pandemic and was based on the recognition that we should see “crisis as opportunity.” The Great Reset argues for a “better form of capitalism” and will be driven by investing in technologies that are devoted to solving the problems of climate change, global poverty, and food scarcity, with the aim of creating a more “resilient, equitable, and sustainable” world. Again, instead of investing in places and communities that most need to be raised up, the initiative encourages governments to strengthen the private sector with further deregulation and give subsidies to companies and entrepreneurs that have scalable business models backing them. To save the world, one must first save capitalism.

The cast of escapists we meet in Rushkoff’s book are fully aware (one hopes) that aggressively extractive, growth-based capitalism has led to proliferating threats to humanity, and that they themselves are complicit in it. But rather than stop or attempt to undo these risks, the goal is to innovate one’s way out of them. Rushkoff likens it to wanting to “build a car that goes fast enough to escape from its own exhaust.”

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →A central element of the Mindset is that one must push the consequences of the relentless extraction of value out of sight and out of mind. Rushkoff calls this “the dumbwaiter effect,” in reference to the invention used by Thomas Jefferson: It was ostensibly a labor-saving device—one that eliminated the need to traverse the stairs from the kitchen to the dining room—but it was, in fact, intended to keep the enslaved people who were serving the food out of view of Jefferson’s dinner guests. Whether it’s ReGen, Seasteading, Elon Musk’s Mars colony, or the billionaires seeking a protected haven in their bunkers, it’s clear that our would-be technocratic saviors dream of making the rest of us invisible. Just as labor, environmental degradation, and human suffering can be externalized on the ledger sheet, so too, with enough ingenuity, can reality itself become an externality.

All of this is a far cry from the techno-utopian rhetoric that marked the turn of the millennium. Those under the spell of the Mindset are the same people who once held out digital technology as the thing that would make the world more open, inclusive, and democratic. We have witnessed the deteriorating optimism of this narrative, which has given way to the realization that the dream of limitless progress is leading us toward disaster, whether it be a climate catastrophe, the unforeseen consequences of AI, or something else. The innovations previously touted by Silicon Valley as instruments of emancipation now appear to be the very things that are hastening the endgame. The rising tide that was supposed to lift all boats may be the one that drowns us.

In turn, we see the sham philanthropy of the tech billionaires, who offer up to us a pseudo-utopian fantasy even as they prepare for Götterdämmerung. If this sounds cynical or overly alarmist, Rushkoff asks us to remember that we just went through a trial run with the Covid-19 pandemic, when “it was the wealthy who bubbled, and the poor who braved the real world to service them.” During this time, it’s estimated that over 200 million people lost their jobs, even as the wealth of the world’s top billionaires multiplied. What’s more, the remote nature of modern life made this transition relatively easy. Many of us were able to stay at home precisely because of our deepening dependence on digital technology, as if it had somehow predestined us for the kind of isolation in which we one day may have to live.

Having already sampled this experience, is there any reason for us to believe that we can rely on the largesse of oligarchs? Can we place our trust in an elite that is clearly all too ready to abandon us? In appealing to the ingenuity of a few intrepid billionaires, techno-solutionism remains deeply cynical about democracy and the possibility of organized action. To mortgage our future on the unproven altruism of a few billionaires is to relinquish any notion of collective agency. But Rushkoff insists that his book not be read as a tragedy, but as a black comedy, in which these characters will ultimately fail in their ambitions to live forever. The appropriate and moral response to such hauteur, as Rushkoff shows us, is laughter.

More from The Nation

The Peculiar Case of Ignatius Donnelly The Peculiar Case of Ignatius Donnelly

The Minnesota politician presents a riddle for historians. He was a beloved populist but also a crackpot conspiracist. Were his politics tainted by his strange beliefs?

The Agony of Aaron Rodgers The Agony of Aaron Rodgers

Is he the world’s most interesting athlete or is he just a washed-up crackpot?

Can You Understand Ireland Through One Family’s Terrible Secret? Can You Understand Ireland Through One Family’s Terrible Secret?

In Missing Persons, Clair Wills's intimate story of institutionalized Irish women and children, shows how a family's history and a nation’s history run in parallel.

Peter Schjeldahl’s Pleasure Principle Peter Schjeldahl’s Pleasure Principle

His art criticism fixated on the narcissism of the entire enterprise. But over six decades, his work proved that a critic could be an artist too.

How the Western Literary Canon Made the World Worse How the Western Literary Canon Made the World Worse

A talk with Dionne Brand about her recent book, Salvage, which looks at how the classic texts of Anglo-American fiction helped abet the crimes of capitalism, colonialism, and more...

Along the Roads That Built Modern Brazil Along the Roads That Built Modern Brazil

José Henrique Bortoluci's What Is Mine tells the story of his country’s laborers, like his father, who built its infrastructure, and in turn its fractious politics.