Audre Lorde Has More to Tell Us Than a Handful of Quotes

A conversation with Alexis Pauline Gumbs, one of the world’s foremost experts on the Black feminist writer, on her biography Survival Is a Promise: The Eternal Life of Audre Lorde.

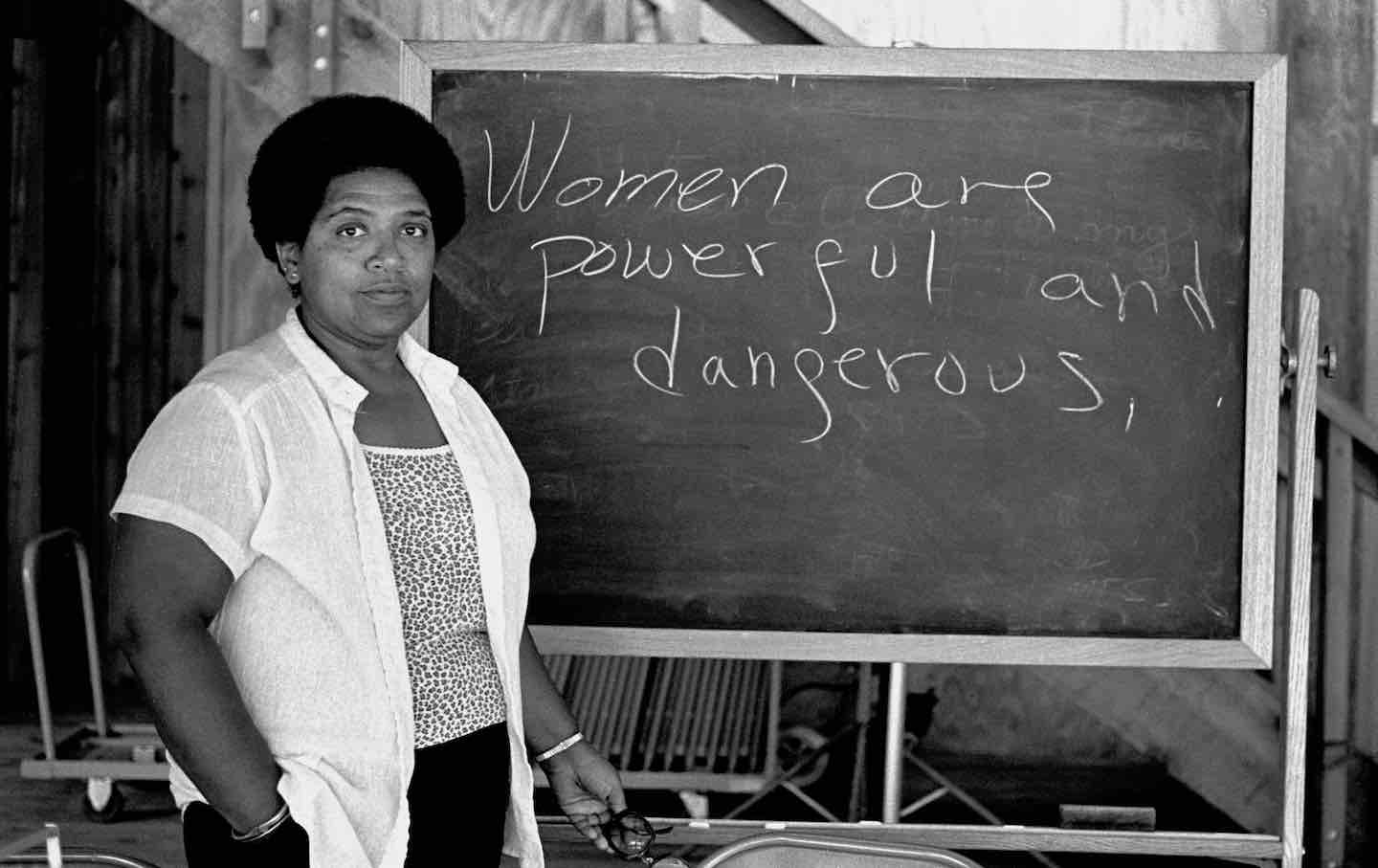

Audre Lorde, 1983.

(Photo by Robert Alexander / Archive Photos / Getty Images)

There is no denying the enduring relevance of Audre Lorde’s work and life. One of the best-known Black feminists of our time, Lorde was a vocal critic of elements of the second-wave feminist movement that overlooked race, sexuality, class, and age. As Lorde put it, “We cannot dismantle the master’s house with the master’s tools.”

Lorde is also well known for her formulation of self-care as a political act: “Caring for myself, she wrote, “is not self-indulgence. It is self-preservation, and that is an act of political warfare.” She believed that surviving, and changing, a society defined by violence and the insistence on difference required those who were marginalized to invest in a politics of healing, not just on an individual basis but through a community-wide ethos. She emphasized the collective, which, as defined by the Combahee River Collective, means focusing on a healthy love for oneself and one’s comrades.

Her ideology of care extended into an internationalist politics of solidarity and anticolonialism: She opposed South African apartheid and supported Grenada’s socialist revolution; she stressed the ethical responsibility of Black people to support Third World struggles for national independence. While her work has often been distilled into catchphrases, her contributions were profound and complex, challenging us to rethink traditional notions of feminism, self-care, community care, and solidarity, as well as the uses of anger and the erotic.

Alexis Pauline Gumbs’s Survival Is a Promise: The Eternal Life of Audre Lorde is both a biography and a celebration of the icon’s life and work, which society has mostly ignored in favor of repeating her most famous quotes. Survival Is a Promise explores Lorde’s life, from her formative years as an unloved, disabled child (nearly legally blind, mute, and requiring special footwear) through her teenage rebellion and her adult years as a celebrated Black lesbian icon (the lover of Frances Clayton and Gloria Joseph), a mother, a cancer survivor, and a woman who died too young—at 58 in 1992—from liver cancer. Crucially, this story is not told in linear fashion: It leaps forward and backward in time, connecting the themes of Lorde’s life to the natural world and the cosmos. It offers a deeper understanding of her poetry, highlighting key moments that shaped her identity and activism, all with the hope of showing how expansive Lorde’s life was. Ultimately, Gumbs’s book argues that Lorde’s legacy lies not just in her powerful words but also in her embodiment of resilience and love in the face of adversity.

The Nation spoke with Gumbs about her personal journey to becoming one of the world’s foremost experts on Audre Lorde, how this biography lays out a more complex narrative that we miss out on when we stop at sharing quotes without context, why there aren’t more biographies like this, the falling-out between Lorde, Barbara Smith, and June Jordan over Israel, and the theme of loss and death that permeates her work. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

—Marian Jones

Marian Jones: When did you first discover Audre Lorde?

Alexis Pauline Gumbs: I discovered Audre Lorde when I was 14, in the young women’s writers’ workshop at Charis Books in Atlanta, Georgia, the oldest feminist bookstore in the country. Linda Bryant, one of Charis’s founders, led workshops in what was basically a storage closet with chairs. Audre Lorde’s books were there one day. I still have Audre’s Collected Poems, which I can see right now. It is always close. But it’s really worn down. I touch it daily. In my childhood, my mother always had writing from Black women writers around, and I believe that my mother, who drew inspiration from Alice Walker, Angela Davis, and others, is the reason why I joined a feminist bookstore writing group. After that, I never let her go. I started using epigraphs from Audre’s poetry in all my high school papers, and I probably couldn’t have articulated it, but I think I knew she was making space for me to express what I needed to express. I just stayed with her. I wrote my college senior thesis on Kitchen Table Press, which she cofounded. I wrote about the works of Audre Lorde, June Jordan, Alexis De Veaux, and Barbara Smith for my dissertation, and I had the great gift of being the first person to conduct research in Audre Lorde’s manuscript archives at Spelman College. I felt obligated to share Audre Lorde with as many people as possible after that archive experience. So I started a night school in my living room for families in my community to have an intergenerational space to engage with her life and legacy. It was called School of Our Lorde. I don’t know how, but Gloria Joseph—Audre Lorde’s life partner—learned about it. She invited me to St. Croix to help her with The Wind Is Spirit, a book she edited about Audre’s work. So, basically, I keep saying yes to Audre.

MJ: Related to that, some readers may think there’s already a treasure trove of biographies about Lorde, but there aren’t. There’s Alex De Veaux’s 2006 book, Warrior Poet, and Lorde wrote about her own life quite often. But there are few full-length biographies. I’m wondering if you have an opinion on why there’s so much information about her yet so few books like this.

APG: Audre Lorde should have thousands of biographies—such a rich life and a profoundly rich archive. There are two biographical films, A Litany for Survival and Audre Lorde: The Berlin Years. Marion Kraft wrote something that’s similar to a memoir—a co-memoir, a collection of 10 essays about her own experience being mentored by Audre Lorde. Also, Gloria Joseph published The Wind Is Spirit, but it’s not in print. It’s a great anthology, so I’m trying to get it back in print. It has many people who knew or were influenced by Audre Lorde writing about her life.

Interviewing so many people in her life for this work has shown me that she died too soon. She lived beyond her doctors’ prognosis, but she only lived to 58. Many who knew her and were in her life still grieve. That direct grief can sometimes act as a barrier to continuous engagement. Personally, for me, it was as if I had been living with Audre Lorde. Writing this biography is another level of really living with this person in a deep way. It was profoundly, profoundly immersive.

MJ: At the beginning of the book, you discuss your plans to challenge the public’s tendency to rely on her most famous essays and coinages and examine her complexity as a person beyond just a historical figure. How does this book do that?

APG: Audre Lorde’s archive and her practice of archiving her work are great gifts, because we have poetry she wrote from childhood through her entire life. So we see her contemplating big ideas. She’s talking about Native American genocide as a kid and trying to write poems about the grief of that. Nuclear apocalypse as a child. She’s thinking about life and death and interpreting Greek myths. In addition to her consistent practice of poetry as a child, we have journals of her high school experiences and how she felt about her teachers and friends. In her final speech at the I Am Your Sister conference, she began by stating what we now call a land-back ethic on Columbus Day, revealing something about her lifelong values. That’s not just because she identified as a Black, lesbian, feminist, socialist, poet warrior, mother. She was a student activist on the Committee for a Sane Nuclear Policy, and she was a student traveling to DC to protest the United States’ murder of the Rosenbergs. We can deeply understand her actions and thoughts if we look at everything.

I also looked at her favorite poems to read. What poems by Edna St. Vincent Millay, Romantic poets, or Walter de la Mare did she memorize and recite? She says, “I didn’t talk until five, and then when I spoke, I spoke in poetry.” What poetry books did she have? How did she use these poems to describe a 5-year-old West Indian girl growing up in Harlem? I tried to go with her when she was collecting rocks and stones. I had to learn so much about geology [laughs]. I wanted to go all the way in with her.

MJ: You spot these patterns and make connections throughout Audre’s life to various cosmic and natural phenomena. For instance, you mention that her nickname for her partner, Frances Clayton, was “the sunflower” and then compare the characteristics of the plant—in particular, its asymmetrical rays of flowers—to their interracial lesbian love and the way Frances tilted toward Audre’s rays of light like a sunflower tilts toward the sun. You also compare meteorites and falling stars to Lorde and her death during the Leonid meteor shower. What prompted you to add these elements?

APG: I do not have a scientific background. I avoided science; I never took physics. I regret it now, because I’m curious about physics. But by incorporating those elements into the biography, I was truly following Audre Lorde’s curiosity, because she went there. She picked up rocks because she liked them. Her daughter tells me she would go to the bookstore and buy all the geology books. When she went to Combahee River Collective feminist retreats, she was known to talk about the moon phases that coincided with their meetings. Her poetry about the moon, stars, earth, volcanoes, and weather is more than just beautiful imagery—it’s literal. It’s a part of the poetics of her life.

I’m sure there are many ways to write a biography, but I thought I really had to follow this young person who read science fiction and was interested in the science behind it. She felt it had implications for her life. She lived down the street from the scientists who invented the atom bomb and changed what humans could do to themselves. She writes science fiction from the perspective of a meteor when she’s in high school, and then she’s still talking about the stars when she wrote A Burst of Light. Without researching geochemical ocean science, I wouldn’t have understood the Kick ’em Jenny metaphor in Zami: A New Spelling of My Name (1982), the underground volcano she uses to describe her relationship with her mother. She’s really the one who inspired me to incorporate those elements, because she never stops.

MJ: You write, “The scale of the life of a poet is the scale of the universe.” What does that mean?

APG: Her final prose work, A Burst of Light, at the end of her life was about this universe, and she was always thinking about it in her journals. I believe that the main takeaway from her entire body of work is that nothing is disconnected. So that’s why the scale of the life of the poet is the life of the universe: because she didn’t see her life as a small thing that was being lived inside of one human body. She saw life as occurring simultaneously on all of these scales. It takes a great poet to even try to say that. I’m struggling to say it right now.

MJ: There’s a passage in the book that touches upon a conflict between Lorde, Barbara Smith, June Jordan, and Adrienne Rich, all of whom opposed Israel’s invasion of Lebanon in 1982. Rich, a Jewish woman, joined the lesbian feminist organization Di Vilde Chayes, which published an open letter in Off Our Backs arguing that their survival as Jews depended on Israel’s existence. And Rich maintained that she was a Zionist in an article in Woman News, leading June Jordan to draft a response expressing her belief that Rich refused to acknowledge their shared complicity in Israel’s violence against Palestinians and Lebanese people.

Then Barbara Smith mobilized against Jordan’s letter because she thought it would polarize the national feminist community. She wrote a response with white Jewish and non-Jewish Black women, disagreeing with both the Di Vilde Chayes open letter and June Jordan’s. Audre Lorde signed this letter. Jordan later wrote to Smith and Lorde in December 1982 expressing her anger and denying being antisemitic. She denounced both antisemitism and Israeli impunity for killing over 40,000 Palestinians. I was a little bit confused here: What was their difference of opinion exactly? Was it just a matter of Jordan’s tone in the letter itself?

APG: Honestly, I believe so—which, to me, is very tragic. I think it teaches us how to communicate specifically about these exact same words: “Zionism” and “antisemitism,” for example. Everyone was against Israel’s invasion of Lebanon, so I think yes. But I don’t think Smith and Lorde agreed with June Jordan and Adrienne Rich on the meaning of “antisemitism” and “Zionism.” Smith and Audre Lorde disagreed with the De Vilde Chayes’s open letters, but they didn’t want anti-racist feminists’ movements and solidarity to fall apart due to perceived antisemitism or how they talked to each other. In her letter, Jordan expresses her rage.

They wrote an open letter in response to Jordan because Smith was worried that Jordan said something as definitive as “You are not my people, and you are just as bad as the white male capitalists.” Smith wanted to push back on an open letter that could pit Black and Jewish feminists against each other. One major issue is that, as June Jordan writes in a letter, she would have preferred Barbara Smith to tell her that personally rather than form a group to write another open letter. So how do we communicate? Specifically, how do we communicate with people we agree with on important issues but disagree with in terms of methods, words, or actions? The reality is that, even though what June Jordan said to agitate sounded very permanent, it wasn’t. At the end of the day, June and Rich did speak to each other, and they did remain friends for the rest of their lives. June called Adrienne Rich one of the bravest and most wonderful people ever, as I wrote in the book. But Audre Lorde and June Jordan never spoke again, as far as I know. Barbara Smith spoke with Jordan again after Audre Lorde’s death. That was the first thing they talked about.

To me, that is a huge Black feminist tragedy. As someone deeply influenced by all three thinkers and writers, it breaks my heart. I wish it weren’t true, so writing about it was the hardest part of this biography. I wish it had not happened; I wish they had found a way to stay in relation through the decades. But they didn’t. So it makes me think about how, as a person on the left and as someone who values language, I can disagree with the language that certain people use—and there are times when we need to stand firm and draw a line—but how do we treat those with whom we want to keep fighting and who we believe are trying to build the same world as us when these conflicts arise? I included it and wrote about it because I think we can learn a lot about ourselves and how we interact.

MJ: We know Lorde opposed the invasion of Lebanon, but you leave it open and write, “We don’t have complete thoughts from Audre about how she felt about Zionism or antisemitism.”

APG: She explicitly denounced Israel’s occupation of Palestine some years later. She probably took a while to get there. Even Adrienne Rich stopped identifying as a Zionist over time. We don’t know what Audre Lorde was thinking about Zionism at this time. Barbara Smith, June Jordan, and Adrienne Rich were writing about it. She wasn’t writing about it during the Lebanon invasion.

MJ: One thing that struck me was her emphasis on death and loss—the themes that tied together so much of her work. How does this relate to the concept of Lorde having an “eternal life,” as you phrase it?

APG: This idea of eternal life is something that is a major pattern in Audre Lorde’s thought process and in her work. She was someone who, from a young age, was thinking about mortality. She is thinking about what lives on from a very young age, specifically in her poetry, and she is discussing the desire to leave a legacy. She’s talking about what will live on, and she’s thinking about it in such broad terms, because she is also allowing for the possibility that the world as she knows it will end when humans nuke themselves into nonexistence. So she puts a lot of rigor and thought into this, and I’m not even going to mention all of the deaths she processes in her journals. Because she feels a responsibility to keep some of the people who died alive, including Alvin, her classmate who died of tuberculosis, and Genevieve, her best friend as a teen who died from suicide. She believes it is her responsibility to continue looking for them, listening for them, and maintaining a relationship with them. She reads the entire newspaper every day, thinking about everyone who has died. She is having nightmares about them. She is then learning about everything that is going on all over the world, including the death that US policy causes all over the world and what imperialism is causing, and she is holding all of it. She does not believe that any of this is unrelated to her. So she must process it. I truly believe that this is part of the reason she has what I refer to as “eternal life.” We feel as if we’ve lost her. You know, she was 58. Those of us who were under a certain age never got to meet her. Some people can now read this book, but they were never alive at the same time as her, and she is still present in our moment. I don’t think it’s very common to see someone focus so consistently on death, which is something that so many people want to avoid or at least put off until later. She didn’t do that. It gave her significant power in terms of how she lived her life, both in terms of what it provided for her and what it allowed her to offer to us.

All in all, I think Audre Lorde’s eternal life is that she still lives in the possibilities that people saw for themselves from reading her work. I think she wanted people to be transformed by the work and then take that energy into their own lives.