The Visions of Alice Coltrane

In the years after her husband John’s death, the harpist discovered a sound all her own, a jazz rooted in acts of spirit and will.

Alice Coltrane, 1970.

(Photo by Michael Ochs Archives / Getty Images)In February 1971, Alice Coltrane released her fourth album, Journey in Satchidananda. It was dedicated, in part, to her husband, the jazz saxophonist John Coltrane, who had died from liver cancer four years earlier. The anguish she felt—along with the rest of the jazz community—was channeled into Journey, a stunning album devoted to healing, even when it seemed impossible in the shadow of such a loss. Not only had jazz been deprived of one of its most significant artists, but Alice had lost her spiritual partner, the man who had introduced her to the harp and Eastern religion.

In the wake of John’s passing, Alice said that God sent her visions of her deceased husband. Spurred by those visions, she put herself through a series of spiritual tests, called “tapas,” in the yogic tradition of austerity. She fasted for days and sometimes slept only two hours a night. Her weight dropped to 95 pounds. She underwent periods of self-harm—cutting her skin, burning herself—which taught her “tolerance, patience, stamina, strength of mind,” as she told the Los Angeles Times in 1987. As Alice saw it, the pain (physical and mental) was supposed to purify her spirit: These trials would force the sorrow to fade.

After her spiritual ordeal, Alice sought further guidance from the guru Swami Satchidananda. He taught her to approach her work with a sense of detachment—or, as she later reflected: “Detached doesn’t mean disliked, it just means that I don’t want this project to consume me. It will if I allow it.” Enriched by Satchidananda’s schooling, she recorded Journey in November 1970 and dedicated the album to both him and Coltrane.

Alice Coltrane: The Carnegie Hall Concert features the pianist, harpist, and bandleader performing songs from Journey at the famed New York venue just a week after the album’s release. Music from the show surfaced in 2018, when the reissue label Alternative Fox released the 28-minute live performance of “Africa” as a single LP. The new double album marks the first time the full concert recording has appeared.

With a large-scale ensemble featuring Kumar Kramer and Tulsi Reynolds on harmonium and tamboura; Pharoah Sanders and Archie Shepp on saxophones; Jimmy Garrison and Cecil McBee on bass; and Ed Blackwell and Clifford Jarvis on drums, it’s a powerful set demonstrating the full breadth of Alice’s artistry, beginning with her own compositions—the quieter, more reflective “Journey in Satchidananda” and “Shiva Loka”—and ending with the more propulsive and volatile songs borrowed from John’s catalog, such as “Africa” and “Leo.” The Carnegie Hall Concert found Alice at a crossroads in her life and career, the moment when her personal perseverance led to a creative renaissance. What happened after Journey reset the critical assessment of Alice and her work. No longer was she just “John Coltrane’s wife”: From 1971 until her death in 2007, she was considered one of the foremost pioneers of an emerging genre, spiritual jazz.

Born in Detroit in 1937, Alice Lucille McLeod grew up gigging around her hometown as a pianist in her own trio and with the vibraphonist Terry Pollard before she moved to Paris in 1960 to study classical music and work with the bebop pianist Bud Powell. In Paris, Alice got a job as an intermission pianist at the Blue Note and became a capable bebop player in her own right. She also married the singer Kenny Hagood and had a daughter, Michelle.

The union didn’t last long, though. By 1963, Alice had split from Hagood and moved back to the States. During a concert in New York, she met John Coltrane at Birdland, the famous jazz club in Manhattan. The two got married in 1965 and had three children together: John Jr., Ravi, and Oran. Alice began playing in John’s band a year later, after his longtime pianist McCoy Tyner, citing creative differences, left the group and went solo. On albums like Live at the Village Vanguard Again!, one can hear Alice branch out into bolder forms of free jazz, setting the course for her sound going forward. She stayed in the group until the band’s final recordings in May of 1967. Two months later, John was gone, leaving Alice to uphold his musical legacy while forging her own path. Before his death, she hadn’t released an album under her own name, but in the late ’60s, her solo career got off to a modest start. Her first two albums, 1968’s A Monastic Trio and 1969’s Huntington Ashram Monastery, were met with polite reviews: As a critic in Downbeat wrote, Alice was “an artist in the process of becoming.”

Also in 1968, in one of her first major performances after John’s death, Alice staged a show at Carnegie where she played her husband’s music and her own in a churchlike atmosphere. It seemed that here she was beginning to channel gospel and spirituality into her performance. While the ’71 show also felt religious, the tone skewed toward Eastern (specifically Hindu and Vedic) philosophy and not the Black American church. To that end, the second Carnegie show was part of a benefit to raise funds for Satchidananda’s Integral Yoga Institute, a nonprofit to which Alice started donating money in 1970.

With songs like “Africa” and “Leo” ending the set, this concert was said to be far more intense than the previous one. By all accounts, the ’71 show was grand and dramatic, right down to the opener with the singer Laura Nyro, whose performance included a monologue on Satchidananda’s controversial relationship advice for women: They had to be a man’s lover, best friend, sister, mother, and maid, “and then he wouldn’t need any other woman,” she claimed the guru said. As mentioned in the liner notes, Nyro’s statement drew one jeer from the crowd. Her retort—“You may think it’s bullshit, but I think it’s true”—drew applause as well. Indeed, there was palpable tension throughout the night.

Alice went to Carnegie Hall still grappling with the depths of her new reality, albeit optimistically. Shortly after she recorded Journey, she went to Ceylon (the country now known as Sri Lanka) for a spiritual retreat, then visited the World Scientific Yoga Conference, where she met other gurus and fellow spiritual students. The retreat helped her find a sense of peace: “The trip to the East gave me the spiritual motivation to come out more—to do more with my music,” she told Essence in 1971. “I also listened to a lot of beautiful sitar and vina [veena] music, and I’m going to use some of the chants I heard.”

I hear a stark shift in her sound around this time. Where A Monastic Trio and Huntington Ashram Monastery utilized the blues and felt traditional in scope, her early ’70s work prioritized ease and enchantment, a bridge between free jazz and Eastern meditation music. Alice would create serene, drifting arrangements that centered her own harp playing against Sanders’s melodic saxophone and McBee’s soothing bass. Here, it seemed, Alice wanted to lull listeners into deeper states of calm. This rang truest on Journey in Satchidananda, which remains, in my estimation, her most powerful and accomplished album. With its droning harps and tanpuras, it was intended to alter consciousness. Journey augured a new stage in Alice’s career when her solo work began to be considered fully on its own, but the album was still not truly appreciated until recently, when outlets like Pitchfork and Rolling Stone reconsidered its status in the jazz (and larger pop culture) canon.

At Carnegie Hall, Alice proved she had a sound all her own, adding fire to John’s compositions, finding a way to make assertive songs like “Africa” even more aggressive and forthright. Where the studio version of “Africa” was swanky and orchestral, with a big band that included Eric Dolphy on clarinet, Reggie Workman on bass, and Freddie Hubbard on trumpet, Alice’s version was raw, carried by screeching horns and extended solos on the drums and bass. The same held true for “Leo”: Where John’s version was psychedelic enough as a sax-and-drums arrangement, Alice intensified the horn section, arranging Shepp’s and Sanders’s instruments into louder and more atonal forms. On these tracks, Alice proved she wasn’t just a practitioner of transcendental harmonies; she had the same verve as other free jazz luminaries.

Perhaps because of whom she was married to, or because of the demographics—white and male—that make up jazz music’s hierarchy and audience, Alice has been unheralded compared with others (namely men) who make the same kind of music. But it isn’t just her: Across the subgenre of free jazz, Black women like the vocalists Linda Sharrock and June Tyson and the poet/singer Jeanne Lee are often left out of the conversation by scholars and critics who can’t see past the testosterone of that era. But Alice and others were keepers of the culture that made the music go. Sharrock—with her piercing, wordless screams that conveyed the angst of Black Americans in the civil rights era—was the star of her husband Sonny Sharrock’s first and best album, 1969’s Black Woman, while Tyson was the most important member of the Sun Ra Arkestra not named Sun Ra. In fact, she was the only woman to have joined his band, a roving collective that sometimes included 22 members. From 1968 until her passing in 1992, Tyson sang, wrote and recited poetry, did choreography, designed costumes, and managed the band’s finances.

Yet, despite Alice Coltrane’s evident prowess, ABC, the parent company of her label Impulse!, wasn’t keen on signing her as a solo act; it did so because she controlled John’s masters and had final say on what got released after his death. In turn, the label let Alice experiment, which led to challenging albums like Universal Consciousness (released later in 1971) and Lord of Lords (a sweeping orchestral suite released in 1973). She continued to push the envelope until 1975, when Impulse! decided not to renew her contract. Alice then signed with Warner and released four albums there. Throughout, her work continued to transform, morphing from spiritual jazz to ambient and New Age by the late ’70s. By the time Transcendence was released in 1977, she’d opted for string-centered compositions without much else on them.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →I have long admired Alice’s strength. That she channeled such anguish, publicly, is monumental—because when a loved one passes, you don’t know if you can imagine life without them. Or if you want to. As the weeks turn into months and the tears don’t arrive as quickly, it’s easy to feel guilty for moving on. I don’t think Alice wanted to forget the pain she felt in those years, and it resonates in the work she made after John’s death.

The visions that Alice mentioned are very real, too. I can’t shake those last few moments of my own mother’s life, when I walked into the room: I still see her breathing slowing down, then stopping, the lamplight brightening her face as she passed away. I see her walking with me through Brooklyn when she came to visit, sharing a private meal in a quiet restaurant near her hotel. There are days when I hear my mother’s voice and feel her hand on my shoulder. I wonder: How could Alice keep pushing forward in the face of such devastation? How did she power through? As Alice mentioned in her interviews, the work of art doesn’t seem so dire when you can see it as a loving act rather than a job. You still take it seriously, of course, but it no longer overrides your peace of mind. The detachment actually improves creativity.

After the second Carnegie Hall concert, Alice traveled with Satchidananda to Chicago and performed another benefit on his behalf. A year later, in 1972, she moved her family to California and stopped following his teachings. Instead, she became a swamini, took on the name Turiya, and by 1976 had changed it to Turiyasangitananda (or “the Transcendental Lord’s highest song of bliss” in Sanskrit). Then, in 1982, she opened her own ashram in Agoura Hills. No longer did she need guidance from Satchidananda—or any other man, really—to feel whole. At last, she had both the knowledge and the wisdom to bring out the glow in others. At the ashram, she wrote and released books through her own private publishing company, then released four cassettes of devotional songs. In 2016, the label Luaka Bop released World Spirituality Classics 1: The Ecstatic Music of Alice Coltrane Turiyasangitananda, a collection she recorded at the ashram. But you don’t get music like that without struggle and the peace she ultimately achieved. That all started in 1971, with Journey and the Carnegie Hall show, two gorgeous works that are still bearing fruit.

More from The Nation

The Peculiar Case of Ignatius Donnelly The Peculiar Case of Ignatius Donnelly

The Minnesota politician presents a riddle for historians. He was a beloved populist but also a crackpot conspiracist. Were his politics tainted by his strange beliefs?

The Agony of Aaron Rodgers The Agony of Aaron Rodgers

Is he the world’s most interesting athlete or is he just a washed-up crackpot?

Can You Understand Ireland Through One Family’s Terrible Secret? Can You Understand Ireland Through One Family’s Terrible Secret?

In Missing Persons, Clair Wills's intimate story of institutionalized Irish women and children, shows how a family's history and a nation’s history run in parallel.

Peter Schjeldahl’s Pleasure Principle Peter Schjeldahl’s Pleasure Principle

His art criticism fixated on the narcissism of the entire enterprise. But over six decades, his work proved that a critic could be an artist too.

How the Western Literary Canon Made the World Worse How the Western Literary Canon Made the World Worse

A talk with Dionne Brand about her recent book, Salvage, which looks at how the classic texts of Anglo-American fiction helped abet the crimes of capitalism, colonialism, and more...

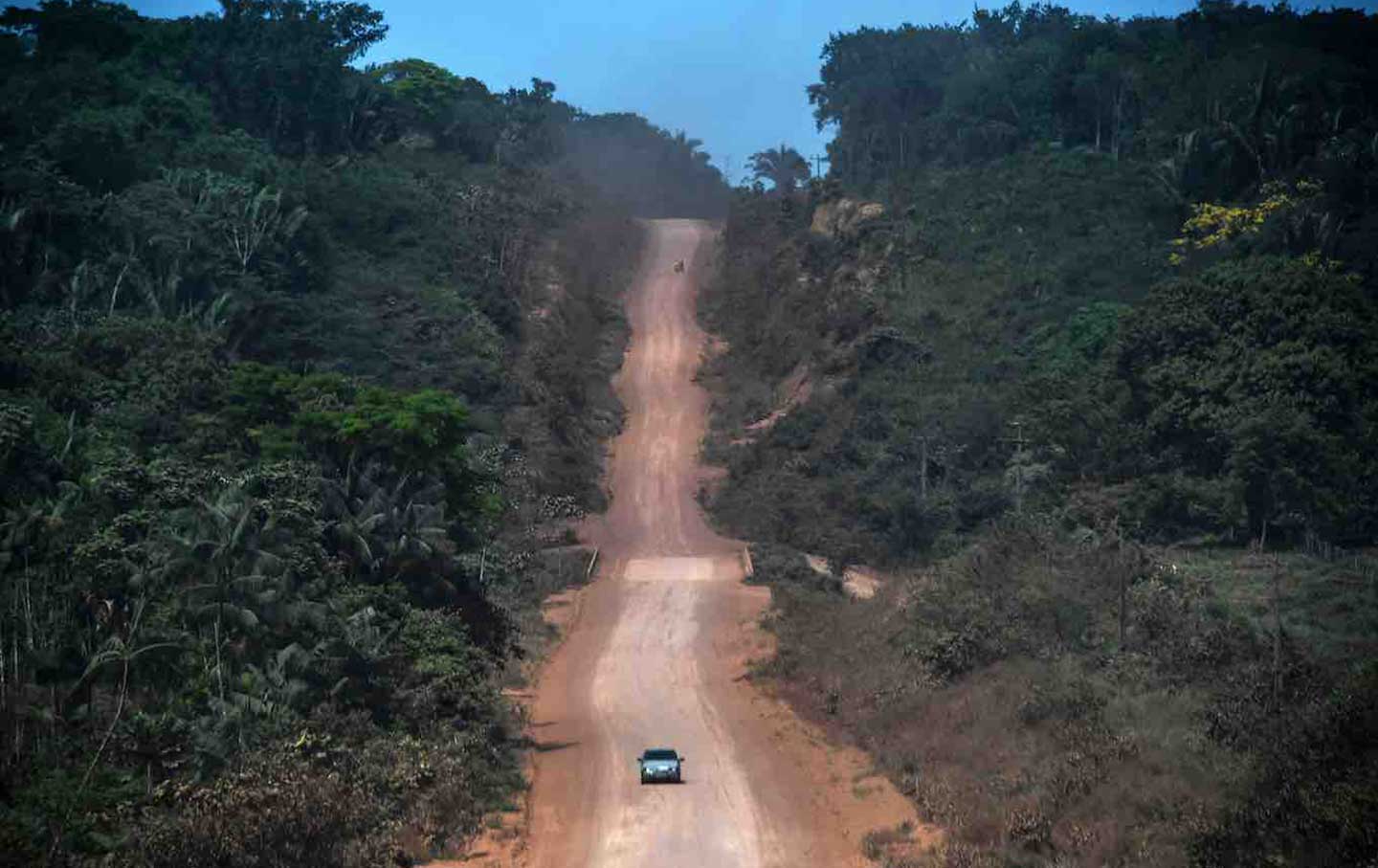

Along the Roads That Built Modern Brazil Along the Roads That Built Modern Brazil

José Henrique Bortoluci's What Is Mine tells the story of his country’s laborers, like his father, who built its infrastructure, and in turn its fractious politics.