Caught in the Climate War

He Devoted His Life to the Climate Movement. Now It Could Get Him Deported.

Canada is trying to remove Zain Haq from the country—something that could set a dangerous precedent.

On the afternoon of October 25, 2021, Zain Haq stepped out of his shared apartment in the quiet Vancouver suburb of Burnaby and hopped into a car with three friends. They made their way toward the Vancouver International Airport, feeling excited.

About a mile away from the airport, the group pulled over near a park and joined a crowd of around 50 people milling about on the damp grass. This was the 10th day of a two-week-long series of road blockades organized by environmental activists, aimed at drawing public attention to their call for an end to fossil fuel subsidies. Haq gave interviews to local media covering the demonstration.

Eventually, the crowd began to make its way out of the park and into the streets. Chanting through face masks, they marched into the middle of a six-lane intersection, effectively blocking the city’s main path to the airport.

Traffic was diverted to nearby roads. News outlets urged travelers to budget extra time for their commutes. Police officers arrived, hovering on the periphery of the demonstration. The protesters settled in.

About 20 minutes into the blockade, police began ordering the protesters to clear out. Most of them dispersed, but not Haq. Along with 17 others, he sat down on the cold pavement, helping to form a barrier that cut across the intersection. The group stayed in place even as police issued a final warning that anyone remaining in the road would be arrested.

“What we’re doing here in the longer arc of history will not be seen as a big deal,” Haq, who is now 22, recalls thinking at the time. “That’s just a traffic jam. We’re here because of a climate emergency.”

As officers approached the group, handcuffs at the ready, some of the protesters lay down on their backs in unison and went limp, like rag dolls. This forced the police to bring in stretchers and lift each person off the street, one at a time. It ultimately took around 45 minutes to arrest everyone. Haq and his fellow activists sang protest songs in the police wagons.

This was not Haq’s first brush with the law. He had already been charged four times for mischief, an umbrella offense in the Canadian criminal code that includes the obstruction of property. Each of these charges stemmed from his participation in climate demonstrations throughout Vancouver. Coming home that October night, he was now staring down a fifth.

Haq would later plead guilty on all five counts, and in July 2023, a provincial court judge sentenced him to seven days in prison, to be followed by two months under house arrest.

The convictions themselves weren’t particularly notable. Haq is one of dozens of climate protesters in Vancouver who have faced penalties or jail time for participating in blockades of roads, bridges, and private property.

But there is one thing that sets Haq apart from most of his peers in the climate movement: He isn’t a Canadian citizen. He comes from Karachi, the largest city in Pakistan. It was in Karachi that he gained political consciousness; that he saw the way climate change can tear holes not just through the environment but through society as a whole; and that he realized that this would be the fight of his life.

Normally, the country listed on Haq’s birth certificate wouldn’t matter so much. But because he is in Canada on a temporary student visa, his participation in climate activism has put him in risky legal territory. On the day of the airport blockade, the Canada Border Services Agency (CBSA) contacted him about his immigration status. If the agency succeeds in removing him from Canada, Haq will be one of the first people in North America to be deported in connection with climate activism.

“I would describe it as a bellwether case,” says Steven Donziger, an American attorney known for his decades-long legal battles with Chevron over its pollution of the Ecuadorian Amazon. Donziger heard about Haq through environmental activist networks last year and later helped put him in touch with his current legal defense team. According to Donziger, Haq’s case could affect “the right of everyone in the world to continue to advocate for climate justice and to hold polluters accountable for their planet.” Haq’s CBSA case also comes at a time when governments in North America and around the world are launching increasingly draconian crackdowns against climate activists. His deportation could hand these governments a powerful new tool in that campaign—and send the message that protest is not something that everyone has a right to engage in.

In person, Haq carries an air of resoluteness and remarkable calm. Despite the uncertainty of his own future, he tends to demur when asked about his personal difficulties, preferring to speak about the injustices borne by other people. Each time we met, he was wearing a modest outfit of gray jeans and a simple top, holding a crumpled baseball cap in his hand.

Haq grew up in a middle-class household in Karachi, the son of a doctor and a journalist. In the summer of 2013, Pakistan was hit with what at the time was considered unusually heavy rain, triggering devastating floods that killed at least 200 people and destroyed tens of thousands of homes.

“I remember actually walking on my way back from school, looking at a group of people who were from the interior of the province that I was in, who were displaced because of the flooding and who had flocked to the city,” Haq says. They had gathered around a government truck that was handing out emergency food supplies. “I saw the person distributing the bags of rations, and…as they would throw it into the crowd, people would just fight each other over it and get really violent. That was the first time I’ve seen people actually fight over food physically.”

Haq and his friends started raising funds to secure additional rations for people affected by the floods. “I remember very clearly feeling like it [was] a drop in the bucket, because it would just vanish right away—a month’s worth of effort,” he says. “That’s when I really started realizing that charity or other forms of helping people aren’t really efficient in combating global emergencies.”

These experiences left a deep impression on Haq and piqued his interest in climate change and politics.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →In 2019, he moved to Canada on a student visa and enrolled at Simon Fraser University in Vancouver. In his first semester, he participated in a global climate strike, which drew 100,000 people in Vancouver alone.

Haq and his classmates also organized a hunger strike to pressure the university to divest from fossil fuel industries. On the day the strike was set to begin, the university announced that it would comply with the students’ demands. Haq became increasingly convinced that civil disobedience was necessary to draw more attention to the climate crisis.

He began participating in demonstrations organized by the Vancouver chapter of Extinction Rebellion, a global network of grassroots activists who use nonviolent civil disobedience to demand a more aggressive response to the climate crisis. He also cofounded a campaign called Save Old Growth to protect the old-growth forests in British Columbia from logging.

“The general philosophy of the theory of change is that it’s fine to inconvenience the public because it’s a form of engaging people in a democracy,” Haq recalls thinking during the airport blockade. “It’s only in a very superficial democracy that we go to the ballot box and we tick a box. But in a true democracy, when we’re faced with existential emergencies, we have the right to nonviolently engage people in a discussion.”

Haq was aware that participating in acts of civil disobedience could lead to repercussions. But to him, the world was—and still is—on a precipice.

“It was important that I was walking the walk,” he says. “In normal society, we’re just tied down by so many [day-to-day] obligations that remove us from thinking about our obligations to future generations and ourselves and our communities.”

In June of 2022, CBSA agents left a notice at Haq’s door. The agency was conducting a review of whether he should be permitted to stay in Canada. Rather than respond immediately, Haq decided to lie low for a few days while he looked for an immigration lawyer. Then he turned himself in.

Haq recalls that the CBSA agents were particularly interested in his work campaigning against logging. “They had all these articles about Save Old Growth that they were going through, and they had a lot of questions about what I was doing with [the organization],” he says. At the end of the interview, “they essentially said that I hadn’t been attending classes…so they were going to detain me on the basis that I violated my study permit.”

The CBSA detained Haq for 48 hours and issued a departure order requiring him to leave the country voluntarily within 30 days, though the order is currently on pause while Haq’s criminal proceedings are under way.

According to its website, the CBSA prioritizes departure orders based on “safety and security grounds, including for national security reasons, organized crime, crimes against humanity and criminals.” But at the time of Haq’s detention, he hadn’t yet been convicted of any crimes. The mischief charges against him wouldn’t be adjudicated until almost a year later.

Instead, the CBSA issued the departure order on the basis that Haq had failed to make what the agency determined to be adequate progress toward his degree, undermining his eligibility for a study permit. Haq had been on academic probation twice because of poor grades, but he says that he was nonetheless devoted to pursuing a degree and was still going to class.

The CBSA doesn’t have clear standards on what constitutes inadequate progress toward a degree. Plenty of students—citizens and internationals alike—skip lectures or flunk classes. According to Randall Cohn, Haq’s immigration attorney, the CBSA has removed people in the past for study-related reasons. But such cases usually involve egregious behavior: In 2018, for example, authorities removed a man who had reportedly entered the country as a student to attend a particular university and instead had taken on a full-time job in a different city.

Haq believes that the agency used his academic issues as a pretext to order his removal from the country—one that would sidestep potential accusations that it had targeted him because of his political activities.

The CBSA declined to comment on Haq’s case, citing privacy limitations. However, it did provide a general statement: “The decision to remove someone from Canada is not taken lightly…once individuals have exhausted all legal avenues, they are expected to respect our laws and leave Canada or be removed. The Canada Border Services Agency has a legal obligation to remove all foreign nationals who are inadmissible to Canada…and who have a removal order in force.”

Haq’s immigration ordeal coincided with another series of natural disasters in Pakistan. In the summer of 2022, Karachi saw flooding so severe that it dwarfed the devastation Haq had witnessed a decade earlier. At least 1,700 people died, and more than 10 million were left without access to clean water.

This summer, Haq was finally sentenced for the mischief charges he’d accumulated over the years, along with a charge for violating the terms of his bail to attend a climate march in 2022. As the judge overseeing his case ordered him to a week of incarceration, millions of hectares of forest were burning in Canada, blanketing swaths of the rest of the world with record levels of pollution.

Haq can no longer attend school, but he’s been reading a lot in his downtime, revisiting favorites like Thomas Paine’s Common Sense and Saul Alinsky’s Rules for Radicals. He thinks a lot about people who have defied the system in the past, such as Nelson Mandela and Mahatma Gandhi, and their stories have helped him make peace with the precariousness of his own situation.

Haq completed his prison and house arrest sentences this past July. The CBSA hasn’t enforced his removal yet because of a judicial appeal that is still winding its way through the courts. Since then, Haq has been spending time with his partner, Sophia “Tidal” Papp, a 28-year-old fellow environmental activist.

In April, the young couple got married and held a ceremony with friends and family at a community center. Soon after, they applied for permanent resident status for Haq as Papp’s spouse. (Papp is a Canadian citizen.) Their application asks immigration authorities to grant Haq residency on humanitarian and compassionate grounds in spite of his criminal record. The outcome of such applications depends on the discretion of the agency, and the wait for a response can take anywhere from six months to two years. Once his judicial appeals are exhausted, Haq might be ordered return to Pakistan while he awaits a final decision.

“He’s in a certain kind of limbo now,” Cohn says. “Is the government going to actively prioritize his removal or not?”

That Haq is facing removal makes Papp scared and sad. “I would characterize myself as verging on panic at times,” she says. Haq’s family in Pakistan has made peace with his legal ordeals. They chat about once or twice a week by phone but haven’t seen each other since before the pandemic began.

Haq’s legal quagmire is part of a growing trend of state repression against climate demonstrations. In Britain, a protester originally from Germany is facing deportation for scaling a bridge and unfurling a banner that read “Just Stop Oil,” forcing police to shut off roads and disrupt traffic. In Australia, two activists had their student visas canceled on “public interest” grounds following their participation in climate protests in Sydney. In France, the government forcibly disbanded the group Les Soulèvements de la Terre (Earth Uprisings) after clashes with police, accusing the movement of “eco-terrorism.”

Around the world, activists are facing criminal investigations, charges, and incarceration—from anti-logging and anti-mining activists in Australia to advocates calling for an end to oil and gas projects in Europe. India has jailed climate protesters and raided nonprofits opposing coal mines. Environmental groups in Uganda have been shut down by the government. In September, the United Nations expressed “grave concern” over a spate of arrests of climate activists in Vietnam. In the US, climate activists have been charged with domestic terrorism and racketeering and prosecuted for shutting off existing pipelines or blocking the construction of new fossil fuel infrastructure, among other acts.

Climate and environmental activism has also become among the deadliest forms of activism to pursue. In a 2022 report, the environmental human rights group Global Witness estimated that at least three land defenders are killed each week around the world. The Guardian reported in April that at least 24 land defenders had been murdered, disappeared, or jailed across Mexico and Central America in the first three months of 2023 alone.

The United States has not escaped this trend: In March, Manuel Esteban Paez Terán, the activist known as Tortuguita, was gunned down by Georgia state troopers while protesting the planned “Cop City” complex in a forest near Atlanta.

“If my removal is enforced…it solidifies people’s skepticism of changing things within the system and within the government,” Haq says. “Canada’s in a place where a decision needs to be made around whether I will be rehabilitated into public life or if I’ll be deported. And that has implications in terms of the relationship between the climate movement and the government.”

Activists worry that the threat of imprisonment or deportation will have a chilling effect among young people. The steady drumbeat of prosecutions in British Columbia—around a dozen other protesters have been sentenced over the past two years for actions similar to Haq’s—has taken a mental toll on those engaged in environmental defense there. One of Haq’s fellow activists told me that it is common for people to step away from the work to recuperate. Then there’s the worry about fragmentation and infighting. Faced with the risk of jail time, activist networks have fractured because of schisms over strategy and blame. Some of Haq’s former peers have secured lighter sentences for similar charges of mischief, in part by claiming that they were misled or manipulated into civil disobedience.

If Haq is deported, it could set a precedent for future removal orders.

“It’s important that people who do the frontline defense of the earth be protected,” Donziger says. “It’s critically important that their freedom to advocate be protected and that when they engage in civil disobedience, they don’t get retaliated against politically through the criminal justice system.”

Haq’s friends say his departure would be a blow to the morale of the climate movement in Canada. “Zain gives a lot of hope to a lot of people,” says Kathleen Higgins, an activist who participated alongside Haq in the October 2021 airport blockade. “He’s able to stay so steadfast and keep a moral certainty.”

Not everyone is so admiring. At Haq’s trial in March, Ellen Leno, the prosecutor on his case, asked the sentencing judge to order Haq to serve three months in prison. She felt that he deserved a tougher sentence because he hadn’t expressed enough remorse for his acts of civil disobedience.

When I ask him about Leno’s comments, Haq says he is unbothered. He didn’t have it in him, he explains, to put on a show of contrition in order to get a lighter sentence: “I thought it would be disrespectful of me to lie about feeling apologetic or remorseful.”

In another world, Haq could have gotten his university degree, then a job, and then permanent residency status, securing his footing in Canada before engaging in civil disobedience. But even as a teenager, he says, that path didn’t feel like a real choice.

“When I was 19…I remember thinking that if I’m always in this sort of sweet, safe space, then I’ll always stay within my comfort zone and not act in ways that I need to act in order to do what needs to be done to prevent catastrophe,” he says. This was the moment he decided to make environmental activism the central focus of his life, no matter the cost.

“At this point,” Haq says, “it’s harder for me to live a conventional life than to live a life in service to the climate movement.”

Can we count on you?

In the coming election, the fate of our democracy and fundamental civil rights are on the ballot. The conservative architects of Project 2025 are scheming to institutionalize Donald Trump’s authoritarian vision across all levels of government if he should win.

We’ve already seen events that fill us with both dread and cautious optimism—throughout it all, The Nation has been a bulwark against misinformation and an advocate for bold, principled perspectives. Our dedicated writers have sat down with Kamala Harris and Bernie Sanders for interviews, unpacked the shallow right-wing populist appeals of J.D. Vance, and debated the pathway for a Democratic victory in November.

Stories like these and the one you just read are vital at this critical juncture in our country’s history. Now more than ever, we need clear-eyed and deeply reported independent journalism to make sense of the headlines and sort fact from fiction. Donate today and join our 160-year legacy of speaking truth to power and uplifting the voices of grassroots advocates.

Throughout 2024 and what is likely the defining election of our lifetimes, we need your support to continue publishing the insightful journalism you rely on.

Thank you,

The Editors of The Nation

More from The Nation

Cornell Championed “Free Expression.” Then It Rolled Out Protest Restrictions. Cornell Championed “Free Expression.” Then It Rolled Out Protest Restrictions.

The university’s overhauled expressive activity policy has been criticized by both pro-Palestine advocates and student and faculty governing bodies.

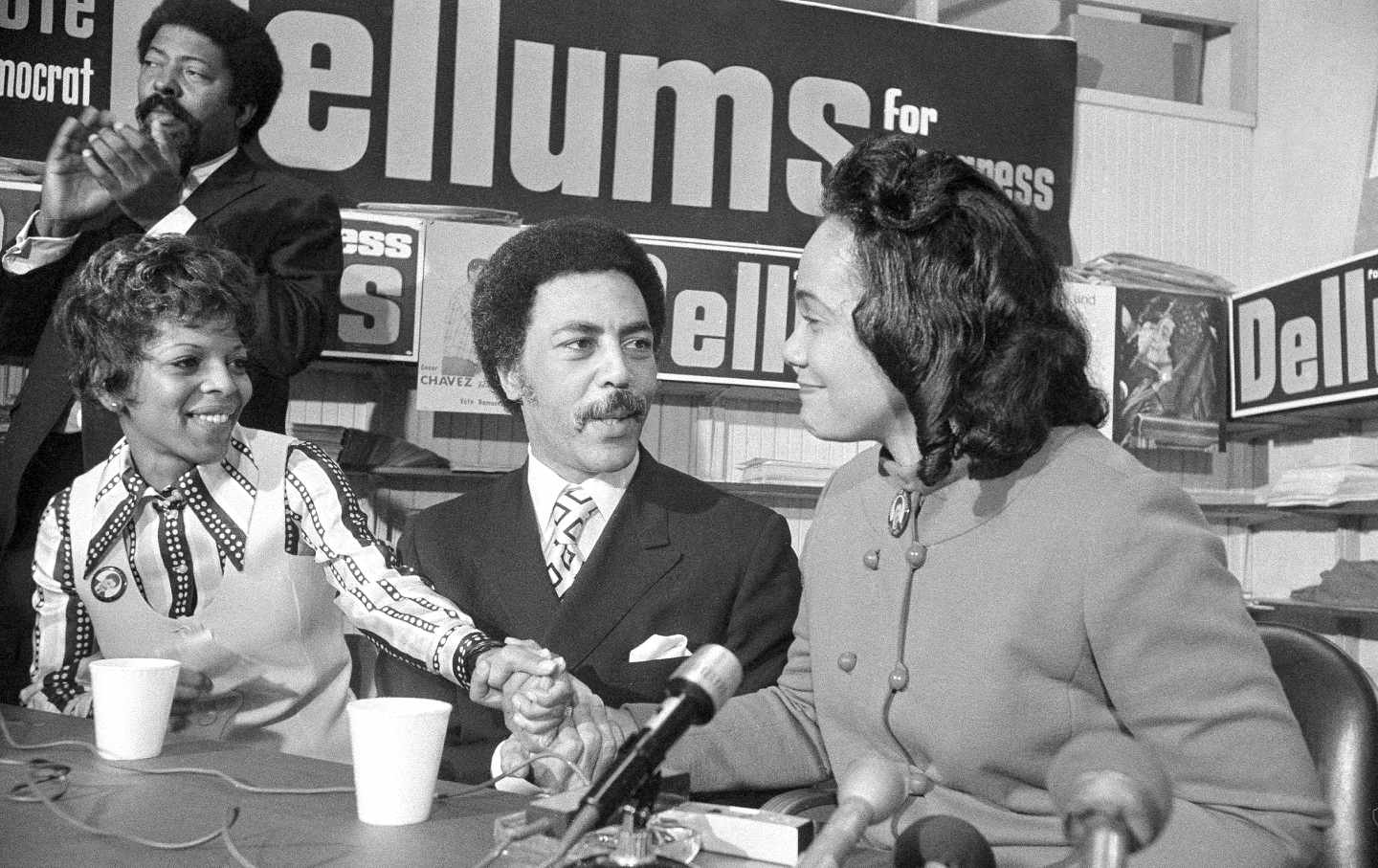

What the Movement for Palestine Can Learn From the Fight Against Apartheid What the Movement for Palestine Can Learn From the Fight Against Apartheid

The successful push to change US policy toward South Africa provides a useful blueprint for our current moment.

A Faster Path to Collective Bargaining: Majority Sign-Up A Faster Path to Collective Bargaining: Majority Sign-Up

Though approval of unions is at historically high levels, membership remains low. One way to change that is to make it easier for workers to form a union—and to start bargaining.

Grad Students Are Unionizing in Droves. Can Postdocs Lead the Next Wave? Grad Students Are Unionizing in Droves. Can Postdocs Lead the Next Wave?

Postdoctoral fellows are vital to universities—running labs, training students, and writing grants—while being overworked and lacking adequate job protections.

The Call Is Out for Mass, Simultaneous Strikes in 4 Years The Call Is Out for Mass, Simultaneous Strikes in 4 Years

These labor leaders are organizing for 2028. Cooperation across unions and sectors—if carried out on a large scale—would be unprecedented in the 21st-century United States.

What’s Next for the Pro-Palestine Student Movement? What’s Next for the Pro-Palestine Student Movement?

“We are not just going to let campus life start as normal."