It was an ordinary Saturday at the Museum of Modern Art. Tourists flowed through galleries, clogged lines at the bathroom, meandered through the institution’s three gift shops, and looked at special exhibitions—such as An-My Lê’s photographic meditations on perpetual violence and diaspora.

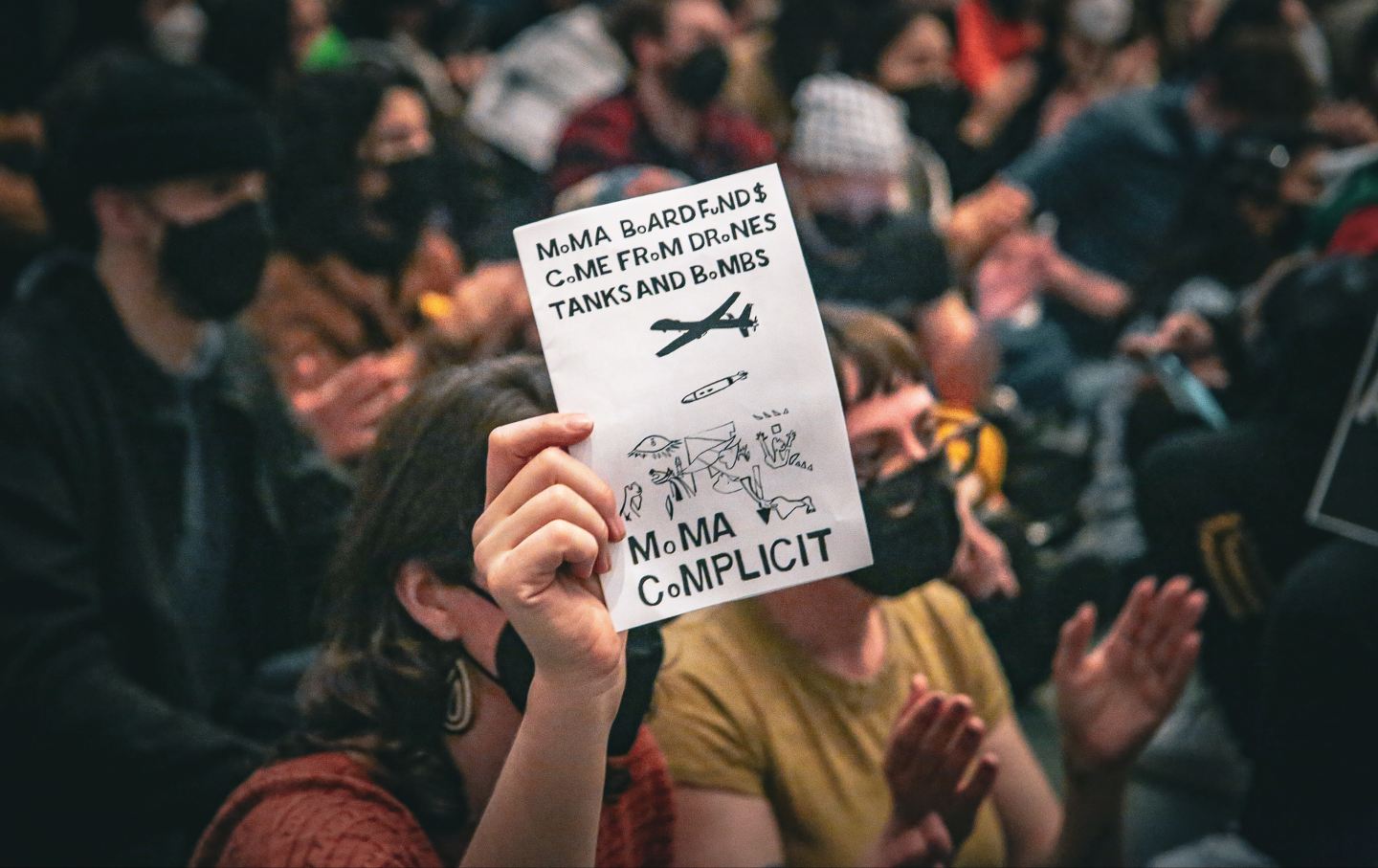

Then, at 3:30 pm, in a gallery tucked into a fourth-floor corner, one group of masked patrons congregated beside an assemblage of objects evoking racialized violence in the 1960s South and began to distribute bright-yellow brochures. Some people reflexively turned them down; others thumbed through the pages. “MoMA trustees fund genocide, apartheid, settler colonialism,” the brochures read.

The same scenes were playing out in dozens of galleries across the museum. Then, at least 500 protesters (including the authors of this piece) flooded towards the MoMA atrium and occupied the museum’s central space.

The air cracked with a familiar chant: “Free—Free—Palestine!” A ten-foot-long banner reading ceasefire now was dropped from a balcony overlooking the atrium, followed by an even larger one, flowing down four stories to the ground, each hand-painted letter an incantation: free palestine from the river to the sea.

Soon after, MoMA had shut down completely. It would not reopen until the following day. Visitors were ferried to the exits. Outside, a soft-spoken museum employee was assisting would-be museumgoers with refunds. “They’re protesting Gaza—our trustees are funding it,” he explained. “We can’t let you see the artwork. There are too many protesters.”

A couple coming from Washington, D.C., turned to leave. “Good for them, bad for us,” they said.

The action, organized by an autonomous collective of cultural workers and activists, was the largest of several recent pro-Palestinian demonstrations targeting art institutions in New York City. As the brochures indicated, this protest—which organizers called a “deoccupation” of the museum—was aimed squarely at MoMA’s board of trustees. A statement from the protesters called for “the immediate removal of board members with direct ties to genocide, apartheid and settler colonialism.” The trustees under critique included Paula Crown, whose family fortune originates from the weapons contractor General Dynamics, which saw its stock surge more than 10 percent after October 7 and manufactures the MK-84 bombs that Israel has dropped on Gaza. The board’s honorary chair, Ronald Lauder, heads the World Jewish Congress, which has condemned the ICJ’s ruling that Israel may be committing genocide and pushed U.S. officials to continue their support for Israel.

The broader goal, though, was similar to many other pro-Palestine mass actions of recent months: the disruption of business as usual. Protesters projected Palestinian art onto the walls and read a letter from a woman living under siege in Gaza. Colorful webs from an exhibit representing resistance to environmental threats swayed over the head of a speaker from the Palestinian Youth Movement, who accused MoMA of “artwashing”—using land acknowledgments and exhibits on decolonial struggle to obscure its benefactors’ war profiteering.

As the protest continued, security guards hovered around the group and conferred quietly with NYPD officers, but did not direct them to make arrests. Confronted with a crowd several hundred strong, the art institution faced a public relations dilemma around how to respond, said one of the action’s organizers, who uses the alias Abu el-Mamoun. At a private institution like a museum, protesters are more able to “dictate the terms of engagement,” he said. “This kind of leverage is less likely to happen in the streets.”

For one of the protesters, who works at what she called “one of the top two or three galleries in the world,” her grievances extended beyond MoMA’s leadership and into the broader industry’s silence about the war. “I’m happy to have found this group because no one in the art world is doing or saying anything,” she said. “I can’t talk about it at work. I’m afraid of losing my job because you’re not supposed to bring politics into the workplace.”

Another participant, Nathaniel Mothing, worked for MoMA for seven years. He quit last April after facing what he described as retaliation and surveillance for participating in 2021’s Strike MoMA protests, which sought to expose trustees’ complicity in human rights and environmental violations around the world, including in Palestine.

Back then, Mothing said, he and another then–staff member anonymously told Hyperallergic that the 10 weeks of protests “were just tilling the soil and planting the seeds.” This action, Mothing said, fulfilled their promise to return.

While some of those present worked in the art world, many came to the action through existing organizing networks formed in response to the war in Gaza. One pod of participants, for example, first came together for the October mass civil disobedience at Grand Central organized by Jewish Voice for Peace but has since participated in a number of other actions and organized its own.

“People are connecting from different spaces and actions and creating groups of affinity and trust,” said el-Mamoun.

These relational organizing networks have been critical for executing large-scale direct actions in secret, especially as social media repression of pro-Palestine organizing intensifies (Within Our Lifetime, a group that has led pro-Palestinian actions for months—including a concurrent protest on Saturday at the Brooklyn Museum—was banned from Instagram just this week).

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →Around 5:30 pm, protesters shuffled out to the street and continued their disruption outside, projecting Palestinian art on the museum’s façade and marching down Sixth Avenue.

Demonstrators accomplished their immediate goal of creating a crisis for the museum, but getting action from policymakers and MoMA leadership will require sustained pressure. “Our demand was to divest from genocide, divest from Israel, divest from weapons manufacturing,” said another organizer, who goes by Octo. “That’s a huge demand that one singular action is probably not enough to accomplish.”

For el-Mamoun, though, the MoMA takeover demonstrates how disciplined, creative collective action can happen when people trust each other to show up. “The magical, beautiful, powerful, transformative thing is when you’re flowing into the atrium and the banners are dropping,” said el-Mamoun. “It’s over. And it’s unstoppable.”

Take a stand against Trump and support The Nation!

In this moment of crisis, we need a unified, progressive opposition to Donald Trump.

We’re starting to see one take shape in the streets and at ballot boxes across the country: from New York City mayoral candidate Zohran Mamdani’s campaign focused on affordability, to communities protecting their neighbors from ICE, to the senators opposing arms shipments to Israel.

The Democratic Party has an urgent choice to make: Will it embrace a politics that is principled and popular, or will it continue to insist on losing elections with the out-of-touch elites and consultants that got us here?

At The Nation, we know which side we’re on. Every day, we make the case for a more democratic and equal world by championing progressive leaders, lifting up movements fighting for justice, and exposing the oligarchs and corporations profiting at the expense of us all. Our independent journalism informs and empowers progressives across the country and helps bring this politics to new readers ready to join the fight.

We need your help to continue this work. Will you donate to support The Nation’s independent journalism? Every contribution goes to our award-winning reporting, analysis, and commentary.

Thank you for helping us take on Trump and build the just society we know is possible.

Sincerely,

Bhaskar Sunkara

President, The Nation