City Limits

Sunnyside Yard and the quest for affordable housing in New York

Sunnyside Yard and the Quest for Affordable Housing in New York

Constructing new residential buildings, let alone those with rental units that New Yorkers can afford, is never an easy task.

One of the most memorable promises that new York City’s newly inaugurated Mayor Zohran Mamdani made during his campaign was to freeze the rent for tenants of the city’s 1 million rent-stabilized apartments. The idea sounds simple, suggesting that there’s a quick and easy way for a mayor to tackle one of the city’s most insoluble problems.

But nothing in New York is ever quick and easy. One of the complicating factors is that the mayor can’t freeze the rents himself. He needs the approval of the city’s nine-member Rent Guidelines Board, which votes annually on whether landlords can increase the rents on regulated apartments and, if so, by how much. The board is appointed by the mayor, but it’s largely regarded as independent and data-driven. This is not to say that a rent freeze can’t be done. Under Mayor Bill de Blasio, the Rent Guidelines Board froze the rent three times during his two terms: in 2015, in 2016, and in 2020, during the Covid pandemic.

The proposal also faces a backlash from those in the real estate industry, who argue that a rent freeze will undermine the solvency of the landlords who typically own what are known as “naturally occurring” rent-stabilized buildings: smaller, older buildings that are in perennial need of expensive maintenance.

However, the real issue when it comes to Mamdani’s signature housing proposal is straightforward: It’s not enough. On its own, it’s not big enough or radical enough to tackle the real problem, which is one of supply and demand. New York City, after all, has a population of 8.5 million and a rental vacancy rate of 1.4 percent.

Mamdani clearly knows this. In a position paper issued back in February 2025, when he was still a blip on the political radar, he vowed to “triple the City’s production of publicly subsidized, permanently affordable, union-built, rent-stabilized homes, constructing 200,000 new units over the next 10 years.” He also promised to “triple the amount of housing built with City capital funds,” creating “200,000 new affordable homes over 10 years for low-income households, seniors and working families.” Four hundred thousand new units may not be enough either, but it’s a start—and building this housing would surely be one measure of his success as mayor.

As most of his predecessors learned, building affordable housing is challeng ing, and past mayors tended to pad their achievements. Over the fiscal year 2025, for example, the previous mayor, Eric Adams, “built” or “preserved” 33,715 affordable units and claimed that by the end of his single term, 425,000 units “will have been built, preserved or planned for.” Similarly, de Blasio announced at the end of his two terms that he’d reached his goal of creating and preserving 200,000 units: “Over the administration, more than 66,000 affordable units have been created and another 134,000 have been preserved.”

If only “preserved” and “planned for” units were enough to erase the shortage of housing for working families. Indeed, if units “planned for” dependably led to housing built, de Blasio could take credit for one of the most impressive initiatives imagined in New York: a master plan for developing Sunnyside Yard in Queens. This mile-and-a-half-long expanse of busy rail yard, jointly owned by Amtrak, the Metropolitan Transportation Authority, and General Motors, represents the scarcest commodity in New York City: 180 acres of open land. Drafted by the Manhattan-based Practice for Architecture and Urbanism (PAU), the Sunnyside Yard master plan was a thing of beauty—a deft mixture of different building types and generous open space, complete with illustrations of children playing in car-free streets. It looked more like Denmark or the Netherlands than Queens. And the written description was, if anything, even more upbeat: “12,000 new 100 percent affordable residential units, 60 acres of open public space, a new Sunnyside Station that connects Western Queens to the Greater New York region, 10 schools, 2 libraries, over 30 childcare centers, 5 health care facilities, and 5 million square feet of new commercial and manufacturing space that will enable middle-class job creation.” It was (and remains) the most utopian thing I’d ever seen proposed for New York City. However, it was released in early March of 2020, on the eve of the pandemic shutdown of pretty much everything.

PAU’s vision for Sunnyside Yard was, in fact, the feel-good antithesis of Manhattan’s Hudson Yards. The two developments used the same strategy, decking over working rail yards to create a building site; the key difference was how the deck would be funded. At Hudson Yards, the developers paid for the deck, and everything they built on top of it was intended to help them recoup a billion-dollar investment. The beauty of the Sunnyside plan was that the city would build the deck. According to Adam Grossman Meagher, who was running the project for New York’s Economic Development Corporation, the $5 billion that the city would have to spend on the portion of the deck that would support buildings was comparable to the amount the city would have to spend to acquire plain old land—except that nowhere in New York City does a comparable amount of land exist. Utopia, as it happens, doesn’t come cheap.

At the time, the whole thing struck me as lovely but improbable, something that desperately needed to happen but, because of Covid and the fact that de Blasio was approaching the end of his second term, probably never would. Even during those awful months of early 2020, PAU’s founder and creative director Vishaan Chakrabarti was surprisingly optimistic, seemingly able to see beyond the fog of Covid: “This is part of why you do master planning,” he told me. “You don’t know something like this is going to happen. But it tees things up for the future.”

That future, however, came and went. The project, released too early in the pandemic and too late in de Blasio’s tenure, has since gone “completely dormant,” Chakrabarti told me in a recent conversation. Before anything could be built there, the yard would have to “be rezoned in accordance to the plan,” and the MTA would have to kick-start the project by building a commuter rail station. The rezoning, which would’ve demanded an enormous amount of political will and acumen, and the existence of a rail station might have positioned the project for a “big federal grant to build a platform,” Chakrabarti says, adding: “There’s no way to build a platform without a federal grant. And this is what’s so frustrating. Mayor Adams, when this plan was still fresh in people’s minds…could have applied for Biden infrastructure money to build the platform.” But he didn’t. And the likelihood of a federal grant ended when Trump returned to office (the startling bromance between the president and the new mayor notwithstanding).

The Sunnyside Yard saga, however, reminds us that accomplishing anything major in New York City requires decades. A mayor (with the exception of Mike Bloomberg, who stuck around for three terms) is in office for a maximum of eight years. So Mamdani will have to get moving.

This is why smart mayors take advantage of—and need to build upon—the work done by their predecessors. As Marc Norman, the Silverstein Chair and associate dean of New York University’s Schack Institute of Real Estate, recently told me, success for Mamdani—or any other mayor—requires using what’s already in the pipeline: “A lot of it depends on who the mayor was before them.”

In fact, Adams has helped Mamdani: The former mayor “had a very ambitious housing plan,” Norman points out, one that Mamdani should find useful. Adams’s incremental rezoning of the whole city, a plan known as the “City of Yes,” offers the incoming mayor a toolkit and a set of strategies to allow more housing to be built in every type of New York City neighborhood.

The City of Yes plan is also projected to help generate 82,000 homes over the next 15 years by encouraging infill development: buildings with a couple of floors of apartments over retail in commercial areas; accessory dwelling units in single-family neighborhoods; and smaller units than had previously been allowed under New York’s building codes. “Mamdani’s going to be able to take credit for the things that happen under [the plan], even though it passed under Adams,” Norman points out.

Even so, whatever City of Yes might facilitate, it’s still not enough. For one thing, as a nation, we no longer build housing. The Faircloth Limit, drafted by North Carolina Senator Lauch Faircloth and signed in 1998 by President Bill Clinton, capped the number of public housing units in the United States at close to 1.28 million, the number that existed on October 1, 1999.

Today, housing is only indirectly funded by the Feds. Depending on whom you ask, this is either a blessing or a tragedy. The mid-20th-century practice of urban renewal, in which massive complexes were constructed that wound up serving as warehouses for the poorest of the poor, has been supplanted by a system that hinges on the private sector. Funding for affordable housing still comes from the federal government, but indirectly, in the form of low-income tax credits. The credits are given to developers of affordable housing, who sell those credits to investors. Public money is still an essential part of the package, but it’s laundered through the private sector. As a result, the process of funding affordable housing is byzantine and slow-moving.

A number of private developers are experts at working the cumbersome system. For example, Jonathan F.P. Rose, the founder and CEO of Jonathan Rose Companies, has been building affordable housing since 1989. He’s known for large-scale affordable and mixed-income projects and is currently developing Gowanus Green, a 100 percent affordable-housing development that includes 995 units in six buildings, on the site of a former gasworks in Brooklyn. The list of funding sources for the project is a mile long.

Like many others in the real estate world, Rose questions the value of Mamdani’s proposed rent freeze and cites the potential for unintended consequences. He points out that half of the affordable-housing developments built with tax credits and owned by nonprofit organizations are already losing money and warns that “if they continue to lose money, they’ll go bankrupt.” As a private developer, the advice he has for Mamdani—and for the government in general—is unsurprising: “Get out of the way. We have a whole series of ridiculous regulations that just waste a whole lot of time.”

Other private developers of affordable housing operate at a smaller scale. Andrea Kretchmer, a founding principal at Xenolith Partners, is about to close on a loan that will allow her firm to start the construction of a 95-unit building on the site of a former police station in the Brownsville neighborhood of Brooklyn. It was vacated by the city in the mid-1980s and, Kretchmer tells me, “a nonprofit in the neighborhood bought it and has been holding on to it since 2002, trying to figure out what to do with it. And we’ve been working for 11 years to get it financed and approved.”

Note that it’s taken over a decade for Kretchmer to assemble funding for a relatively small project. And even as developers like her angle for funding to create new affordable housing, existing units, for a variety of reasons, disappear. “We are losing units faster than we can replace them with new construction,” she says. “It’s like we are running on a treadmill that’s going faster than you can run, and we’re falling backwards.”

Chakrabarti, meanwhile, has moved on from Sunnyside Yard. In 2023, he and his team at PAU did a research project for The New York Times called “How to Make Room for a Million More New Yorkers.” It was a study of the city in which they “identified more than 1,700 acres of underutilized, developable land: vacant lots, single-story retail buildings, parking lots.” They also included office buildings that could be converted into apartments. It was like a scavenger hunt in which they looked for places where more housing could be added without rezoning or changing the character of neighborhoods. Unlike Sunnyside Yard, though, this project is not at all utopian. Instead, it’s a hyper-pragmatic approach to solving a problem, one that could serve as a template for Mamdani’s housing goals.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →Chakrabarti points out that “everyday working-class people in New York City can sometimes make up to six figures if they’re union employees,” but even those people “can’t afford market-rate housing…and that’s because the market’s broken. Our big developers,” he continues, “have zero interest in building 50-unit, transit-oriented developments in the Bronx, Brooklyn, and Queens. They are geared towards building 300-, 400-, 500-unit buildings.”

Of course, much of the “affordable” housing that’s been constructed in New York City over the past couple of decades has been generated by those same big developers. With a strategy called inclusionary zoning, developers can build taller or fatter towers if 20 or 30 percent of the apartments are set aside as “affordable.” It’s a clever end run around the funding issue, but—surprise!—it’s not enough. In part, this is because the strategy—labeled “creating affordable housing out of thin air” by NYU’s Furman Center—can succeed only in those parts of the city that are affluent enough to support the building’s market-rate units, meaning that it won’t work for many of the sites identified by Chakrabarti’s mapping project. “We need a new family of small-scale developers who can, in a really unimpeded way, build working-class housing on those available sites,” he contends.

When I mention Chakrabarti’s theory to Kretchmer—that what we need is developers interested in turning parking lots into 50-unit buildings—she is enthusiastic: “You know, we like parking lots. That’s our jam.” And when I asked her about some other small firms doing work like Xenolith, she lists a number of them, including Type A Projects (another firm owned by women) and Kalel Companies. Clearly these developers exist.

The new mayor, meanwhile, has appointed Leila Borzog as the deputy mayor for housing and planning. She was the Adams administration’s executive director for housing, so she knows what’s in the pipeline, and as the deputy commissioner of the Department of Housing Preservation and Development under de Blasio, she helped organize a competition: Big Ideas for Small Lots NYC.

So parking lots could well be Mayor Mamdani’s jam, too. His administration might be smart enough to effectively deploy what’s already there, taking the City of Yes and running with it, shoehorning in non-luxury housing wherever it might fit. There are, for example, 20,714 surface parking lots in New York City, according to one survey. Not all of them need to be used for new housing, but redeveloping the city one parking lot, vacant lot, or disused commercial building at a time would move the dial in 50-unit increments until someday, eventually, there is enough.

Your support makes stories like this possible

From Minneapolis to Venezuela, from Gaza to Washington, DC, this is a time of staggering chaos, cruelty, and violence.

Unlike other publications that parrot the views of authoritarians, billionaires, and corporations, The Nation publishes stories that hold the powerful to account and center the communities too often denied a voice in the national media—stories like the one you’ve just read.

Each day, our journalism cuts through lies and distortions, contextualizes the developments reshaping politics around the globe, and advances progressive ideas that oxygenate our movements and instigate change in the halls of power.

This independent journalism is only possible with the support of our readers. If you want to see more urgent coverage like this, please donate to The Nation today.

More from The Nation

Bad Bunny's Stunning Redefinition of "America" Bad Bunny's Stunning Redefinition of "America"

His joyous, internationalist, worker-centered vision was a declaration of war against Trumpism.

How Capitalism Transformed the Natural World How Capitalism Transformed the Natural World

In her new book, Alyssa Battistoni explores how nature came to be treated as a supposedly cost-free supplement of capital accumulation.

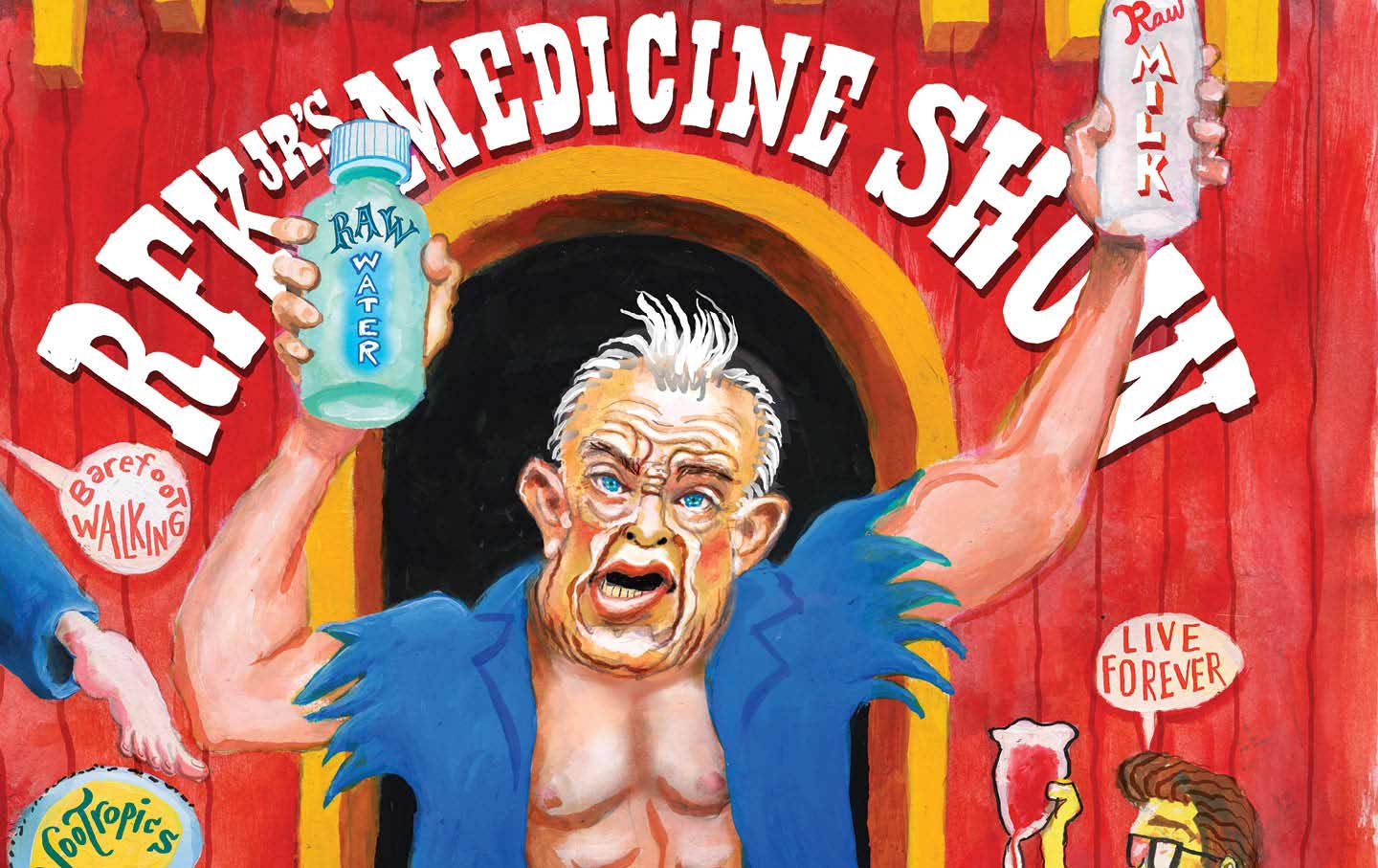

How the Far Right Won the Food Wars How the Far Right Won the Food Wars

RFK’s MAHA spectacle offers an object lesson in how the left cedes fertile political territory.

What the Pro-Choice Movement Can Learn From Those Who Overturned “Roe” What the Pro-Choice Movement Can Learn From Those Who Overturned “Roe”

The anti-abortion movement was methodical and radical at the same time. The abortion-rights movement must be too.

“Shut Up and Serve”: The Professional Tennis Players Fighting a Rigged System “Shut Up and Serve”: The Professional Tennis Players Fighting a Rigged System

An antitrust lawsuit calls the professional tennis governing bodies “cartels” that exploit players and create an intentional lack of competitive alternatives. Can players hit back...

The Real Harm of Deepfakes The Real Harm of Deepfakes

AI porn is what happens when technology liberates misogyny from social constraints.