David Cronenberg, Transformed

Two works—a new film, The Shrouds, and a career-spanning monograph by the film critic Violet Lucca—present a more sanguine image of the master of body horror.

In 1975, David Cronenberg’s debut feature film, Shivers (aka They Came With From Within, aka The Parasite Murders), was trashed by his Canadian countrymen. Writing under a pseudonym, the esteemed Canuck literary critic Robert Fulford wrote that Shivers was “the most repulsive movie [he’d] ever seen.” More galling to Fulford than the “perverted sex and violence” (in Shivers, a parasite, passed on by sexual contact, turns its victims into zombies) was how the film had been funded: It was bankrolled by government grants, meaning that Canadian taxpayers had footed the bill. (To drive home the point, the review was titled “You Should Know How Bad This Film Is. After All, You Paid For It.”)

Books in review

David Cronenberg: Clinical Trials

Buy this book

The resulting controversy was initially a boon for the 32-year-old Cronenberg, who was thrust into the center of a morality debate and received ample press coverage as a result. The film’s producers cherry-picked withering quotes to bolster Shivers’s publicity. Cronenberg took to the press to defend his film and lambaste the country of his birth. “Where else but in Canada,” the filmmaker wondered, “do you get a critic…who is more conservative, more reactionary than a government body?”

So intense was the national controversy that it resulted in Cronenberg and his young family being evicted by an elderly landlady, who claimed he had violated a morality clause embedded in his lease. As the critic Violet Lucca describes it in her new book David Cronenberg: Clinical Trials, the director attempted to defend himself again, this time by arguing that the obscenity charges were just the opinion of one critic. But, Lucca writes, “the landlady informed Cronenberg that she was a friend of Fulford’s and trusted the writer completely.” Beyond speaking to the rare instance of a film critic’s influence, the story reveals something about Cronenberg’s persistent ability to be misunderstood.

Now 82, Cronenberg has survived various scandals (his 1996 auto-erotic sex thriller Crash incited a new moral panic in the UK, which almost banned the film; in the US, rumors circulated that AMC theaters had stationed extra guards on the premises to prevent curious-minded minors from sneaking into the movie), carving out a distinct, even distinguished career that slashes through genre, style, and mainstream acceptance. Clinical Trials positions Cronenberg as a director who has always dared to be disreputable by courting controversy, but also as a “profoundly philosophical” filmmaker whose work can stir feelings of the mysterious, the numinous, even the divine. Cronenberg, in Lucca’s reckoning, has always been a complex, contradictory artist, one who “would assert his unrelenting serenity and normality while being saddled with epithets like ‘Dave Deprave,’ ‘The Baron of Blood,’ ‘Canada’s King of Horror,’ and ‘The King of Venereal Horror.’”

Cronenberg’s early entries into the “body horror” genre—1975’s Shivers, 1977’s Rabid, 1979’s The Brood—were doused in buckets of blood and goo. In the ’80s, films like Scanners (1981), Videodrome (1983), The Fly (1986), and Dead Ringers (1988) could be plenty gory but also suggested a deeper philosophical bent. They reflected on the nature of outsider identities, on the brain-warping power of the media, and on the very limits of the human body. They were not merely perverse; they were about perversion. Adaptations of works by William S. Burroughs (Naked Lunch), Don DeLillo (Cosmopolis), J.G. Ballard (the aforementioned Crash), and David Henry Hwang’s play M. Butterfly furthered Cronenberg’s reputation as one of Hollywood’s few true intellectuals. The successes of the crime thrillers A History of Violence (2005) and Eastern Promises (2007) demonstrated that he was fully capable of playing within the system—provided he could still crack a few heads open or let loose with a linoleum knife.

Recent decades have been less kind to Cronenberg. Shrinking box-office receipts, and a more muted critical reception, have led to smaller budgets, which in turn has seen Cronenberg slipping proudly back into disreputability. His latest, The Shrouds, serves up images and ideas stranger and more alienating than anything in Shivers; it is clear he’s an artist who is comfortable mucking around on the margins of the industry and the mothballed standards of “good taste.” Another low-budget affair, born out of a scuttled Netflix series pitch and cobbled together with piecemeal international funding (including from the Canadian taxpayer), The Shrouds is an intensely, often uncomfortably personal film that challenges the perception of Cronenberg as a mere provocateur—while being every bit as provocative as any film he’s ever made.

The Shrouds stars the French actor Vincent Cassel as a Toronto technologist named Karsh, whose ludicrous name is matched only by his out-of-place Parisian accent. Karsh’s latest invention is an “enveloping camera,” a high-tech burial shroud that permits viewers the opportunity (if that’s the right word) to bear witness to the corpse’s decomposition via television monitors mounted into the gravestone. With his block of greased-back gray hair and penchant for gray-on-gray suiting, Karsh is an obvious surrogate for Cronenberg; even his name works as a sort-of homophone for Crash.

Also like Cronenberg, who lost his wife of nearly 40 years in 2017, Karsh is a recent widower. The death of his spouse (Diane Kruger) pushed him to invent his enveloping camera as a method of prolonging his mourning. “When they lowered my dead wife into the ground in her coffin,” he explains, “I had an intense, visceral urge to get in the box with her. It was so strong. I couldn’t stand that she was alone in there, and that I wouldn’t know what was happening to her.” Any necrophilic subtext is made even plainer when Karsh pontificates on the need for high-def cameras that permit “deeper penetration” into the nooks and crannies of the spoiling body, or mulls a “haptic” extension that may permit the living the ability to almost touch the dead.

It must be said that this is an odd film, even for Cronenberg. On the level of its visual register, it is flat, lit like a soap opera or Canadian TV drama. The story is simultaneously simple—a sad, delusional man mourns his dead wife—and deliberately perplexing and obtuse. When Karsh’s futuristic graveyard is vandalized, he begins to untangle a global conspiracy that’s attempting to hijack his technology. The presumed culprits include Icelandic environmentalists, a Russian/Chinese hacker syndicate, and a disgruntled brother-in-law (Guy Pearce). The corporate intrigue at first feels needlessly baffling, or at least boring, but it dovetails deceptively with the film’s deeper theme.

Karsh may eroticize his new technology in a way that seems deeply personal. But his merchandising of it is ultimately exploitative—a way of bilking the bereaved by extending their contact with the dead via a proprietary “corpse voyeur” app. Besides being a depressed widower, Karsh resembles another archetype, that of the modern-day “tech bro”: driving around Toronto in a Tesla and retreating to his Japanese-style apartment, complete with its own koi pond. For all his intense horniness, Karsh is not much different from the corporate vultures—or foreign operatives—who want to use his camera shrouds and app as part of a world-spanning surveillance network. In this way, The Shrouds feels doubly confessional: Cronenberg is both exposing his own bone-deep grief and castigating himself for artistically capitalizing on it and his late wife’s memory.

What obsesses Cronenberg here is the idea of a world that exists—and, indeed, may be economically sustained—after death. Corpses are not merely sites of further consumption but catalysts for new relations and modes of understanding. By placing himself in intimate contact with death and all its unforgiving processes, Karsh finds new ways to become “sexually viable.” He takes a new lover (Sandrine Holt) who, as the first woman he sleeps with after his wife’s death, claims his “neo-virginity.” This exciting sense of possibility (of a life after the body) distinguishes Cronenberg’s late-period films.

Previously, the director might have been fairly accused of a certain pessimism. For all of their inventive reconfigurations of the human body and their hype around the “new flesh,” Cronenberg’s films typically resolve apocalyptically. Heads explode. Bodies crumble. Apartment towers full of hyper-sexualized zombie parasites collapse. And despite its gory, pornographic excess, his work reflects a certain conservative tendency. The late left-wing film critic Robin Wood clearly articulated this cynical strain: “Cronenberg’s movies,” he wrote, “tell us that we shouldn’t want to change society because we could only make it worse.” Cronenberg’s explorations—and explosions—of the human body betray, Wood argued, a backward-looking political worldview.

Wood, I think, is undeniably persuasive here. As he outlines it, a certain kind of reactionary horror pulses through Cronenberg’s work. The libidinal glut of Shivers lines up with an antipathy to the “sexual revolution” of the 1960s and ’70s. Likewise, the deformed dwarf-kiddos and icky external wombs of The Brood (1979) evince a basic disgust at all things maternal (the film was released, incidentally, the year that Cronenberg would divorce his first wife). The new-media frequencies of Videodrome (1983) are quite literally cancerous, while the metamorphic ambitions of Jeff Goldblum’s mad scientist in The Fly (1986) end, inevitably, in an assisted suicide by shotgun. eXistenZ, from 1999, seems less a satire about the moral panic surrounding violent video games than an exegesis on why playing first-person shooters is, in fact, bad for you.

Cronenberg’s films are strange and gnarly, but they suffer from a lack of relish. They’re no fun. (Who but David Cronenberg could take the insane, unhinged ick of William Burroughs’s Naked Lunch and make it, by some reverse miracle, so aloof and dull?) He is, after all, the undisputed master of a genre dubbed “body horror,” and his attitude toward these bodies can be regarded as a register of his own revulsion. That is, until recently. In his late work, like Crimes of the Future and The Shrouds, Cronenberg seems more curious about the changing worlds he’s conjured. He is excited by, and even enamored with, bodies mutating, transforming, and decomposing. While all of his films may be about death, it is in his late work that its inevitability has given rise to a cautious optimism about the future—and even life after death—that arises, rather naturally, by the elder statesman of body horror confronting those very same inevitabilities.

In Violet Lucca’s estimation, this less-pessimistic Cronenberg was in plain sight the whole time: He has, in some sense, always been an engaged, even joyous artist, she argues, whose work abounds with great potential. In Clinical Trials, she finds much more to admire in Cronenberg’s films than a critic like Robin Wood (or myself) does. “They’re darkly comic, beautiful, sad, frightening, entrancing, ominous, and profoundly philosophical,” Lucca writes. She sets out to trace this “multifaceted nature” by developing a novel structure that bounces the films against various Jungian psychological conceits: individuation, anima, the shadow, the ever-slippery (especially in Cronenberg) notion of the self. It’s a fun and even fitting frame—the relationship between Jung and Freud, after all, formed the basis of Cronenberg’s 2011 psychodrama A Dangerous Method.

More than a mere clinical dissection, Lucca presents auteur theory as a form of (psycho)analysis, “treating the work itself as an individual: one that grows up, goes through a deeper reckoning of who they are, and then maybe seeks out a shrink.” The book’s first part, titled “Individuation,” works through the early phases of Cronenberg’s career, from his late-’60s short films to The Fly in 1986, tracing them along the Jungian process of self-discovery. In the second part, “Psychotherapy,” Lucca thematically connects Cronenberg’s films (Videodrome, A History of Violence, Eastern Promises, etc.) to the different stages of Jungian psychotherapy, from “Confession” through to “Elucidation,” “Education,” and “Transformation.”

Lucca’s psychoanalytic approach fits a filmmaker whose own concerns traverse the porous boundary between the body and the mind, and treating the work itself as the patient is even more generative, considering the rather obvious maturation in Cronenberg’s movies and thought. And it’s not just about the ostensible elevation from taxpayer-funded Canadian B-movies to Hollywood dramas starring actors like Michael Fassbender, Ed Harris, William Hurt, John Cusack, Robert Pattinson, and Jay Baruchel; it’s about the way Cronenberg seems to have thought through his own anxieties. For all his early desire to shock the audience (and goad the media), Cronenberg’s career trajectory follows an arc of reverse radicalism, in which his early reactionary tendencies have been replaced by a more thoughtful consideration of his own anxieties and revulsions.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →The Shrouds, as with the earlier Crimes of the Future (2022), provide ample evidence of “Dave Deprave” contemplating what happens in the aftermath of mutation, perversion, and even death. Moreover, he seems newly sympathetic to these possibilities. Set in a near-future where bodies have become desensitized to pain, Crimes features Viggo Mortensen as a taciturn performance artist whose body sprouts fresh mutant organs, which are tattooed and then extracted for the delectation of his audience. Throughout the film, Mortensen’s Saul Tenser evades meddling bureaucrats desperate to catalog and obtain such bodily mutations and struggles with his own place in an ever-changing world, one made interminable—perhaps ironically—by global biological mutations that have eradicated pain and disease among the general populace.

Like many of Cronenberg’s protagonists, Saul is at odds with his own body. The difference is that Crimes of the Future ends not in the deterioration or obliteration of the body but in an enraptured reckoning with what the body is capable of and what new forms it can take. Saul learns to accept—and even enjoy—his new flesh, much like Karsh in The Shrouds finds the possibility of continued romance with his dearly departed wife, even as she rots in the ground. These films evoke not a catastrophic end or some restoration of an old order. Instead, they point to some alternative—a great beyond.

In Clinical Trials’ final chapter, “Education,” Lucca describes the goal of Jungian analysis as reintegrating the patient with society in such a way that they may “live in a healthy manner, not harming themselves or others.” This line brings her back naturally (in terms of both theme and chronology) to Crimes of the Future, which ends with its protagonist in a state of blissful ecstasy. “In the end,” Lucca writes, “Saul chooses not to escape from who he is…. Despite his foresight and intelligence, it turns out that his body wasn’t betraying him.” She compares the film’s final shot—a grainy close-up of the performance artist “faintly smiling beatifically”—to the image of Renée Jeanne Falconetti, burning at the stake, at the climax of Carl Theodor Dreyer’s 1928 French silent film The Passion of Joan of Arc.

Comparing a director who was once kicked out of his apartment for making a splattery sex-horror exploitation film with one of cinema’s more austere transcendentalists may seem a bit of a stretch, but there’s little doubt that Cronenberg’s staging of Crimes’ conclusion invites the analogy. Longtime collaborator Viggo Mortensen, in his introduction to Clinical Trials, also draws a line between Dreyer and Cronenberg, calling them “exacting surgeons in their meticulous exploration of human bodies, behaviours, and thought processes.”

Certainly, Cronenberg’s work is marked by its meticulousness, but his strange optimism is the soul of his late work. If Crimes of the Future ends with an ecstatic acceptance of the human body’s new frontiers, then The Shrouds concludes with a newfound eroticism. Karsh escapes Toronto for Budapest with his lover in tow. En route to Hungary, he imagines her in the body of his deceased wife: decaying, missing limbs, riven with scar tissue and stitching. Far from being repulsed, Karsh is aroused.

The film ends with the two passionately making out as their private jet climbs above a veil of black clouds, en route to some uncharted future. The image is as creepy as anything in Cronenberg’s oeuvre, in part because it risks awakening in the viewer similar feelings of arousal at images of bodies ostensibly in distress and decay. It’s discomfiting, but the feeling behind it is powerful. There are still new worlds, new bodies, and new psychological hang-ups to discover. And Cronenberg seems more willing than ever not only to confront but to accept them. There is still life—and love—even after death.

Disobey authoritarians, support The Nation

Over the past year you’ve read Nation writers like Elie Mystal, Kaveh Akbar, John Nichols, Joan Walsh, Bryce Covert, Dave Zirin, Jeet Heer, Michael T. Klare, Katha Pollitt, Amy Littlefield, Gregg Gonsalves, and Sasha Abramsky take on the Trump family’s corruption, set the record straight about Robert F. Kennedy Jr.’s catastrophic Make America Healthy Again movement, survey the fallout and human cost of the DOGE wrecking ball, anticipate the Supreme Court’s dangerous antidemocratic rulings, and amplify successful tactics of resistance on the streets and in Congress.

We publish these stories because when members of our communities are being abducted, household debt is climbing, and AI data centers are causing water and electricity shortages, we have a duty as journalists to do all we can to inform the public.

In 2026, our aim is to do more than ever before—but we need your support to make that happen.

Through December 31, a generous donor will match all donations up to $75,000. That means that your contribution will be doubled, dollar for dollar. If we hit the full match, we’ll be starting 2026 with $150,000 to invest in the stories that impact real people’s lives—the kinds of stories that billionaire-owned, corporate-backed outlets aren’t covering.

With your support, our team will publish major stories that the president and his allies won’t want you to read. We’ll cover the emerging military-tech industrial complex and matters of war, peace, and surveillance, as well as the affordability crisis, hunger, housing, healthcare, the environment, attacks on reproductive rights, and much more. At the same time, we’ll imagine alternatives to Trumpian rule and uplift efforts to create a better world, here and now.

While your gift has twice the impact, I’m asking you to support The Nation with a donation today. You’ll empower the journalists, editors, and fact-checkers best equipped to hold this authoritarian administration to account.

I hope you won’t miss this moment—donate to The Nation today.

Onward,

Katrina vanden Heuvel

Editor and publisher, The Nation

More from The Nation

The Best Albums of 2025 The Best Albums of 2025

From Mavis Staples to the Kronos Quartet—these are our music critic’s favorite works from this year.

Forrest Gander’s Desert Phenomenology Forrest Gander’s Desert Phenomenology

His poems bridge the gap between nature’s wild expanse and the private space of one’s imagination.

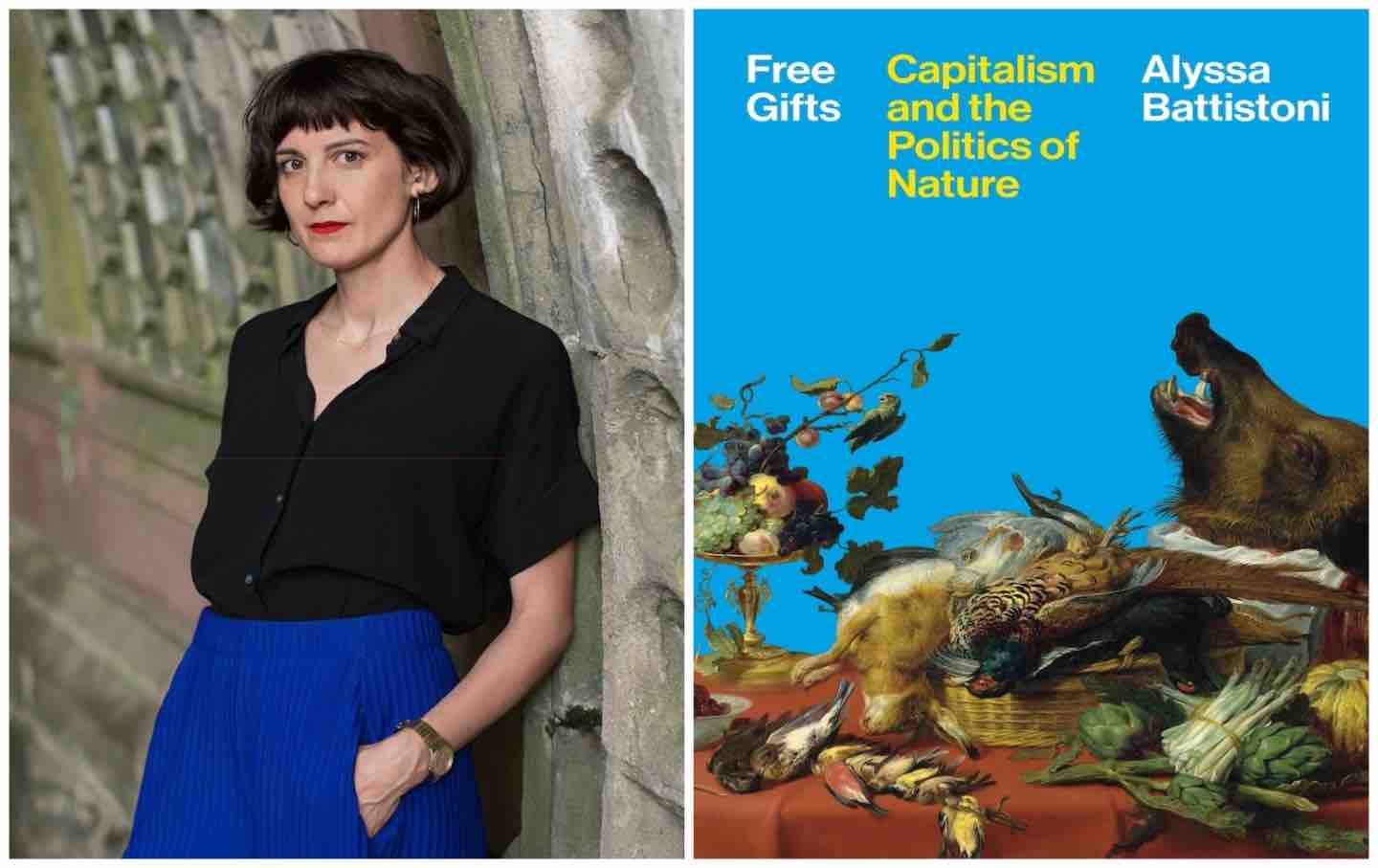

Capitalism’s Toxic Nature Capitalism’s Toxic Nature

A conversation with Alyssa Battistoni about the essential and contradictory nature of capitalism to the environment and her new book Free Gifts: Capitalism and the Politics of Nat...

Solvej Balle and the Tyranny of Time Solvej Balle and the Tyranny of Time

The Danish novelist’s septology, On the Calculation of Volume, asks what fiction can explore when you remove one of its key characteristics—the idea of time itself.

Muriel Spark’s Magnetic Pull Muriel Spark’s Magnetic Pull

What made the Scottish novelist’s antic novels so appealing?

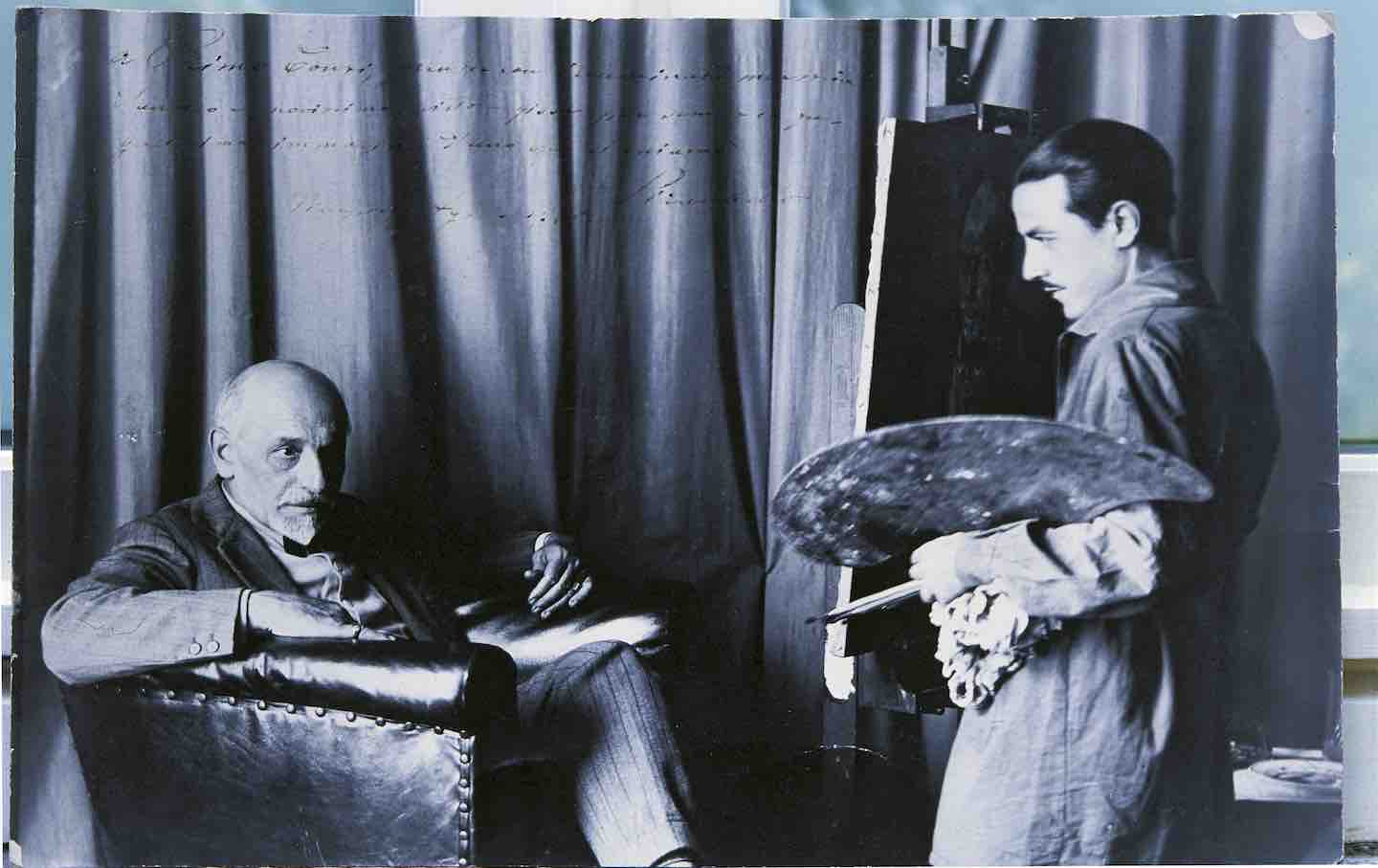

Luigi Pirandello’s Broken Men Luigi Pirandello’s Broken Men

The Nobel Prize-winning writer was once seen as Italy’s great man of letters. Why was he forgotten?