The Americans Stealing Palestinian Land

As the West Bank gets carved up for illegal settlements, US real estate companies are eager to cash in.

Fakhri Abu Diab amid the rubble of his former home.

(Carolina Sophia Pedrazzi)The worst day of Fakhri Abu Diab’s life began at 8:15 am on Wednesday, February 14, 2024. He was alone with his wife in their home, the same modest compound in Silwan, East Jerusalem, where he’d been born 62 years before.

Suddenly, the house shuddered from a deafening blast. The Israeli army had blown open the property’s iron gate. A squadron in battle gear streamed in, pushing Abu Diab back. It was followed by almost 20 border patrol officers, armed and with guard dogs. After the officers were finished, the bulldozers moved in. They flattened everything: the fruit tree he had planted with his mother as a child, the rooms of his grandchildren, the gardens outside.

Abu Diab had seen this coming. He’d been a prominent activist against Israel’s land annexation of Palestinian territories for decades. Israeli forces had been demolishing homes all around him, and he knew that it was only a matter of time before they came for him. He had even alerted journalists, who documented the raid as it happened.

But that didn’t make the morning any less horrifying—or the lingering trauma any less real.

“They bulldozed with such violence,” Abu Diab said later in an interview, his voice breaking. “It felt like our hearts were being crushed by the bulldozers too.”

Abu Diab’s story is, sadly, not unique. It is a tragedy that thousands of Palestinian families have endured over the years. In 2024, around 100 people from Silwan alone were forcibly displaced, their homes torn down brick by brick. Some of these structures had stood since before 1967, when Israel first seized East Jerusalem and occupied the West Bank. In the years since, this occupied land has been further colonized by Israeli settlers, who have weaponized Israeli law and used the overwhelming force of the IDF to encroach further and further onto Palestinian land.

In the Occupied Palestinian Territories (OPTs), there are over 250 Israeli settlements and their precursors, known as outposts. The settlements, which are often heavily militarized, are illegal under international law, but the governments of both Israel and the United States have largely given them free rein. The two countries are directly linked in this colonial project: Tens of thousands of settlers hold dual nationality with the United States.

American Jews can come to settlements in part through a network of real estate companies that specialize in selling Palestinian land to American citizens, facilitated by a 1950 Israeli law that allows any Jewish person to automatically acquire citizenship in Israel. The agencies, which go by names like “My Israel Home,” promote the idea of “putting down roots in the Holy Land” as they market and sell luxury villas in settlements. Meanwhile, to date, millions of Palestinians live in exile in refugee camps, overcrowded cities, and poor neighborhoods across the Arab world.

In mid-August 2025, Israel approved the construction of the E1 settlement, a large project that will bisect the West Bank, effectively making a contiguous Palestinian state impossible. The construction of E1, which will connect Jerusalem to the illegal settlement of Ma’ale Adumim, has faced opposition for nearly two decades from the international community, including the United States. When announcing the green light for the project, Finance Minister Bezalel Smotrich said, “This is Zionism at its best—building, settling, and strengthening our sovereignty in the Land of Israel.”

The International Court of Justice confirmed in 2024 that settlements in the occupied territories were illegal; however, the real estate deals that keep them connected to the United States may have legal significance within America as well. In response, a multifaceted protest movement has sprung up on this side of the Atlantic, combating the sales events on American soil directly while also introducing legal challenges that hope to end the impact of settler expansionism.

Before it was destroyed, Abu Diab’s home was in the Al Bustan neighborhood, a segment of Silwan just 200 meters southeast of the walls of Jerusalem’s Old City. The Israeli Jerusalem Municipality claims that Al Bustan—which means “The Orchard”—is built on an archaeological site where the prophet King David founded his kingdom 3,000 years ago. On this pretext, the Israeli government intends to raze all the homes in Al Bustan to build “King’s Garden” in their place.

Residents and human rights groups claim that the King David Park project furthers the government’s real goal: to expand the existing Israeli settlements in East Jerusalem to create territorial continuity between them while removing the area’s original Palestinian character and presence.

Still, activists like Abu Diab have refused to leave. Since his home was razed, he has lived beside the rubble in a makeshift home caravan, determined not to abandon the land.

Abu Diab’s protest, ironically, mimics the genesis of many Israeli settlements: Colonists arrive first in caravans, setting up small communities to establish a permanent presence, giving the IDF and other government authorities a pretext to expand the settlement and clear out Palestinians.

Once a settlement has been established and expanded, there is often room for new settlers. Thousands of miles away from Jerusalem, real estate companies like “My Israel Home” regularly hold special marketing events in synagogues and other meeting areas, where Israeli and American realtors market the dream of buying luxurious condos in idyllic towns in the Holy Land.

One of the most successful realtors in this space is the founder of My Israel Home: Gedeliah Borvick, an American-Israeli who was born as Gordon Borvick in New York. After moving to Israel in the early 2000s, Borvick built a career selling real estate in his new home to citizens of his birthplace, helping other American families make aliyah, the Hebrew word for migrating to Israel. My Israel Home’s definition of Israel includes all of the Occupied Palestinian Territories.

The real estate agency lists homes and apartments in Israeli towns—many of which were built on the ruins of Palestinian villages from the 1948 Nakba—and in several East Jerusalem and West Bank settlements. One of the agency’s marketing lines, “Come Home,” encourages buyers to view property acquisition as a spiritual journey rather than just a transaction. But that spiritual journey often doesn’t come cheap: In August of 2024, the Israeli government granted special tax cuts for American buyers of houses valued up to 5.6 million dollars. Thus far, Borvick’s pitch appears to be working. My Israel Home’s website is full of enthusiastic reviews expressing gratitude for how seamless the resettlement process has been. “Recipe for Turning 2 Clueless Americans into Apartment Owners in Israel: 1 long-time Yerushalmi with an encyclopedic knowledge of every nook and cranny of Jerusalem, 1 easy-going ex-New Yorker Oleh, who knew our needs exactly without us saying a word, Heap of patience. Touch of passion for their jobs, Sterling reputations within their industry,” one review reads, referring to Borvick and his partner, Eliezer Goldberg. “Yield: 2 very happy Americans who are thrilled to now own their small ‘chaylek’ [portion/share] in Israel.”

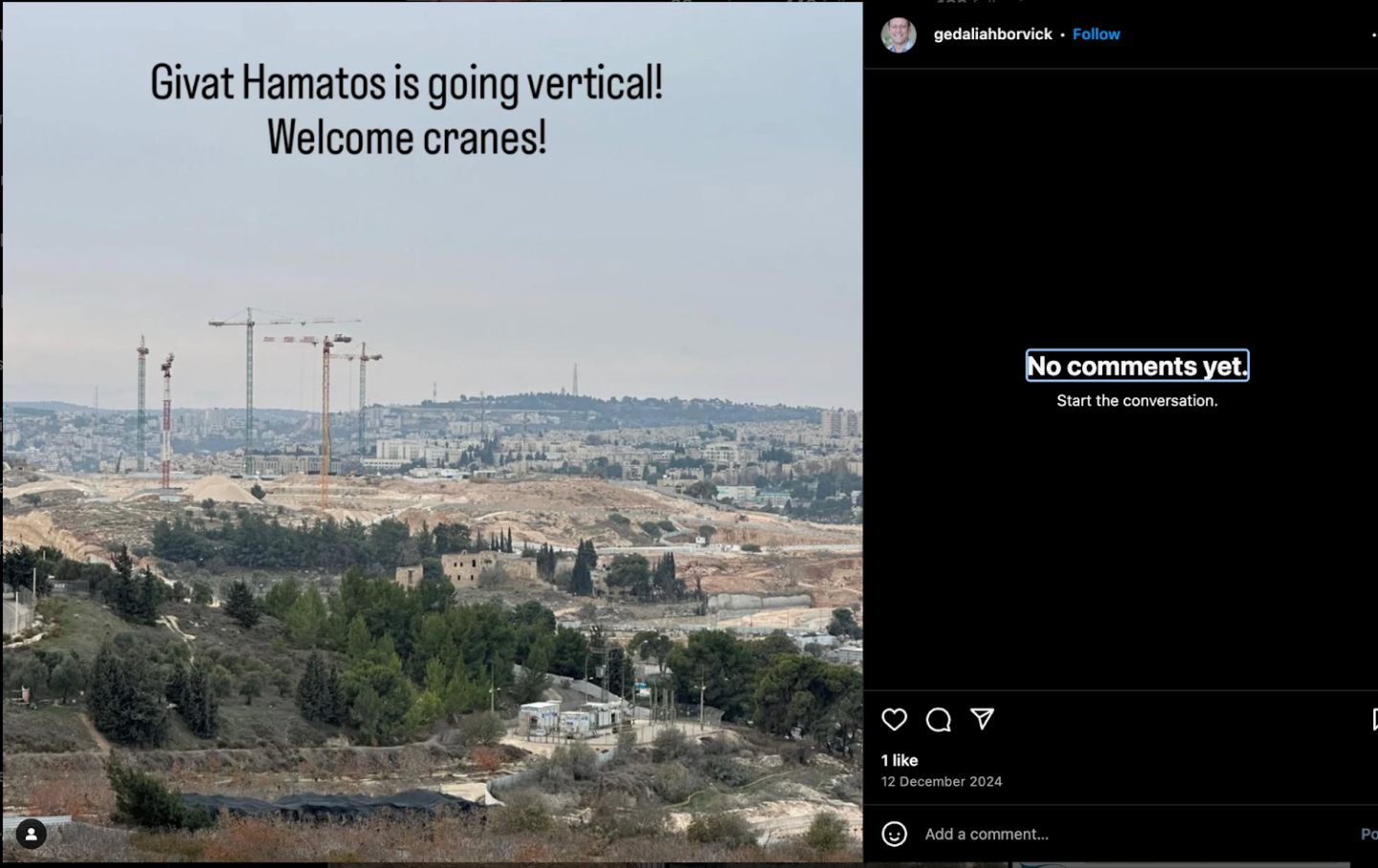

On December 12, 2024, Borvick posted an Instagram photo of a lush, green landscape interspersed with old abandoned buildings. In the background, an arid, rocky terrain with an ongoing construction site was visible. “Givat Hamatos is going vertical! Welcome cranes!” Borvick wrote. Givat Hamatos, a new settlement, is just over three miles away from Abu Diab in Al Bustan, built on roughly 70 acres of confiscated Palestinian land.

Although Abu Diab did not speak directly about Givat Hamatos in interviews, the connection between his experience and the new settlement is clear to Palestinians in Silwan (and all other areas in Palestine that have suffered from land grabbing due to the Occupation). Like other developments in East Jerusalem, Givat Hamatos represents the long arc of a land seizure process that begins with demolitions like the one Abu Diab endured. While he faces the loss of his home today, it may take years, sometimes decades, before that same land is parceled into luxury real estate and marketed abroad. The timeline may obscure the direct link, but for Palestinian families who have seen this phenomenon repeat itself, the trajectory is all too familiar.

Borvick wrote in a blog post on My Israel Home’s website that the development, which includes parks, public buildings, shopping centers, and hotels, would be Jerusalem’s “first modern urban-planned neighborhood,” with the capacity to host 10,000 living units. (The post also claimed that the development is located in “Central Jerusalem,” rather than its actual location in occupied East Jerusalem.)

Throughout the fall of 2024, Borvick’s company promoted the development at a series of events in New York and New Jersey, searching for prospective American buyers willing to consider Givat Hamatos as their future home. Borvick works hard to protect his clients from public scrutiny. In early November of 2024, I caught wind of an upcoming real estate seminar. I e-mailed Borvick asking if I could attend, but received no response. Activists claim that Borvick and other organizers often refuse to share event details with applicants who do not have Jewish names and perform background checks on others. Women who request to attend unaccompanied are often turned away, as Orthodox customs expect a man to be the primary homebuyer. (In June 2025, the makers of the upcoming documentary Stealing Sunset shared a clip of a covertly filmed settlement real estate event. At one point, a realtor is recorded saying, “Yes, [the government] wants to encourage [going beyond the Green Line]”.)

Still, I wanted to see these events for myself. So on the evening of November 7, I drove to Bergenfield, New Jersey, where I had heard of a planned protest at one of Borvick’s events. Outside the venue—a suburban villa in a line of neat row homes on a residential street—pro-Palestine activists faced off against a pro-Israel crowd, separated by metal barricades monitored by New Jersey police. Many of the street’s homes sported “Trump 2024” signs on their lawns and banners blending the Israeli and American flags. Among the pro-Palestine crowd were Jewish anti-Zionist groups holding signs reading “True Jews can’t buy stolen bloody earth.”

The people planning to attend My Israel Home’s event blasted music and waved IDF brigade flags. “We hope your beepers go off,” some pro-Israeli protesters shouted, referencing the Israeli pager attack in Lebanon, which killed dozens and wounded thousands. Across the street, pro-Palestinian activists chanted, “Long live the Intifada.” At around 8 pm, Mr. Borvick briefly exited the venue and danced along to the techno-pop music being played on the pro-Israel side of the protest. (Borvick did not respond to multiple requests for comment.)

There was little direct communication between the two groups. When one adolescent girl from the pro-Israel side tried to engage in conversation with an anti-Zionist rabbi, her parents adamantly insisted that New Jersey police escort her back to her side of the protest. Members of the Zionist groups were hesitant to speak to me as I approached them in my hijab. Explaining that I came from Columbia University did not help, as one man called the institution “that hub of antisemites.” Eventually, a woman named Miriam, who preferred not to share her last name, agreed to speak with me.

She described the pro-Palestinian protest as distasteful and antisemitic, claiming that the event was primarily a funeral for the brother of one of My Israel Home’s executives, an IDF soldier who had been killed in combat two weeks earlier during Israel’s invasion of Southern Lebanon. The land sales event, she said, was merely a coincidence: Given that the community had already assembled for the mourning ceremony, Borvick took the chance to share My Israel Home’s most recent real estate opportunities. Flyers for the event distributed beforehand, however, mentioned the real estate, and not the funeral.

Later that month, I attended a second protest outside of an event in Midwood, Brooklyn, at the Kingsway Jewish Center synagogue. As in Bergenfield, police had separated a raucous crowd of protesters and counterprotesters with metal barriers. “No peace on stolen land,” protesters chanted in response to the event’s advertisements, which offer attendees the chance to “own a piece of the Holy Land.”

Standing in the middle of the barricades, able to access this section through a press pass, I approached the Zionist side, where a woman named Chana Lerner said that the pro-Palestine protest was “asinine,” and claimed that the event wasn’t marketing property in contested territories. She claimed her people had been “radicalized” because they had been hurt by antisemitism. Around her, pro-Israel protesters chanted, “We will destroy Lebanon.”

As I was speaking to Lerner, a man wearing a “Make America Great Again” T-shirt and an IDF baseball cap approached us. “You are a fucking terrorist!” he shouted at me. “You need to die.” Lerner apologized on his behalf.

The group opposing these events in New York and New Jersey is a local chapter of PAL-Awda, or Palestinian Assembly for Liberation and Return. One organizer of the New York and New Jersey chapters, a woman in her 70s named Tova, told me she had come to the movement after decades of pro-Palestinian activism. Tova was born in Rehovot in 1949, in a house that she later learned had been taken from a Palestinian family by Israeli militias. Her parents, Hungarian-Jewish survivors of the Holocaust, had moved to Palestine after WWII, hoping to escape European antisemitism after being denied asylum in several Western countries, including the US. (Her parents eventually obtained asylum in Canada.)

PAL-Awda’s campaign against Israeli real estate sales includes a legal challenge facilitated by another group called the PAL Commission on War Crimes, Justice, Reparations, and Return. PAL Law Commission, as they’re known, have been documenting the real estate events and serving cease-and-desist letters to real estate companies like My Israel Home and their sponsors. The group argues that because My Israel Home’s events are held in synagogues and cater specifically to Jewish-only audiences, they violate the 1968 Fair Housing Act, which they say applies to entities that “aid and abet in the discrimination.”

Gabor Rona, an expert in international human rights, humanitarian, and criminal law, told me that these kinds of legal investigations may find stronger grounds under the Alien Tort Statute (ATS), which grants federal courts jurisdiction over certain civil actions brought by noncitizens. Rona said that under the Fourth Geneva Convention, transferring civilians out of occupied territory or transferring the occupying power’s own population into occupied territory is considered a war crime, which could give a Palestinian plaintiff grounds to sue in a US court under the ATS.

The International Court of Justice and the UN General Assembly have defined these territories as under occupation, and even the Israeli Supreme Court has recognized that the West Bank is not part of Israel’s sovereign territory. But the road to bringing such a case in the United States is still extremely difficult, particularly given the American reluctance to apply international law to Israel and Palestine. Rona said that actions by companies like My Israel Home present a secondary complication as well, as many of the settlers being transferred into “occupying territory” are not Israeli but American.

Still, activists think that putting this defense to the test is both expedient and necessary. Rona said that a legal claim might be successfully introduced in a US federal court, with one key condition: The plaintiff must be a Palestinian who has been directly affected by a real estate sale in the United States.

There is no shortage of Palestinians who have endured this fate. Musa Said Abu Mohammed is one of them. Abu Mohammed, 61, and his family have lived in the village of Al Khader for many generations. Al Khader—in Arabic, roughly “the green one”—is located in an idyllic part of Palestine known for its fertile land, terraced hills, and proximity to Solomon’s Pools, an archaeological site dating to the first century BCE.

Until 2000, Abu Mohammed and his family relied entirely on agriculture for economic sustenance. They lived off their land in Al Khader, tending to the olive and fig trees that grew there. For years before that, he told me, settlers had approached him, offering up to a million dollars to buy his land, but he refused every time, “no matter how high the bid got.” When it became clear that he wouldn’t sell, the Israeli army forcibly expelled him, destroyed his water well, and denied him access to his land forever. When presented with the option of becoming a potential plaintiff, Abu Mohammed dismissed it, suggesting it would only cause them more trouble and heighten the family’s vulnerability by becoming a target.

Today, an Israeli road cuts directly through Abu Mohammed’s former farmland. Route 60 divides the West Bank from east to west, passing by the settlement of Efrat, which was cofounded in the 1980s by Shlomo Riskin, a rabbi from New York. Efrat is still a growing community: Villas in the settlement are popular offerings from Israeli-American real estate firms. Over the years, it has expanded to encompass over 1,500 acres of confiscated Palestinian land, much of it taken from Al Khader. Some 85 percent of Al Khader’s remaining territory is under Israeli military and administrative control, and only Israelis are allowed unfettered access to the main throughway into and out of the area.

Last winter, I video-called Abu Mohammed. He answered from his living room in one of the homes in Al Khader, surrounded by his family. They live in the small remaining portion of the village that is not controlled by the IDF. “How does it make you feel to know that, on the land where your olive and fig trees used to be, American settlers are now living in luxury villas?” I asked.

He paused, a hopeless smile on his face. “I swear to God, it breaks my heart,” He said. “And it makes me angry. But what can I do?”

The displacement of people like Abu Mohammed is part of an ongoing process of expansion that Omar Shakir, director of Human Rights Watch for Israel/Palestine, argued constitutes ethnic cleansing.

Many different tools and tactics are used to take Palestinian land, Shakir said. The Israeli government will often arbitrarily declare that Palestinian territory, even privately owned land, is state land, designating it either for settlements, military training facilities, or environmentally or archaeologically protected sites.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →“They will say, ‘This was previously owned by Jewish Israelis, and therefore, we need to take over the land,’” said Shakir. “But, of course, they don’t follow that rule when it comes to Palestinian land previously owned inside Israel.”

Settlers themselves often hasten this process, confiscating land by force and using it for agricultural purposes, before calling the army to help them hold their claims.

Many human rights organisations, such as B’Tselem, have long been recording the unabated settler violence in many areas of the West Bank. The region of the South Hebron hills is particularly affected. One field researcher, who asked to remain anonymous because of threats he receives from Israel, explained that armed settlers will approach Palestinian farmers and intimidate them systematically, often forcing them to leave their homes, ultimately leading these communities to flee to more urbanized places.

In the summer of 2024, during my last trip to the West Bank, I met Akram Abu Sharekh, from the tiny hamlet of Zanuta, a farming village a dozen miles west of Masafer Yatta, the setting of the Oscar-winning documentary No Other Land. I first visited Zanuta back in 2022, and already, at that time, its 150 or so residents were apprehensive about having to face forced displacement. Since October 7, Abu Sharekh told me, settlers in the nearby colonies and outposts had become increasingly aggressive.

“They come with the drones and terrify the sheep,” he said. In the fall of 2023, they came in force. The IDF nearly completely demolished the hamlet, forcing its residents to relocate to the town of Ad Dhahriya.

“The settlers put pressure on us because they want us to abandon the land,” Abu Sharekh told me after we walked over the rubble of what used to be his home, “but I’m not going anywhere.”

The land had belonged to his family since the 1950s. However, during Ramadan in 2024, the Israeli administration helped settlers seize the land and proceeded to demolish everything he had built. As he drove me in his semi-functioning pickup down the unpaved roads of arid Southern Hebron, he told me that the settlers’ attacks forced him to move his wife and children into the city, away from land that used to be safe for sheep and families alike.

“Even the Americans’ sanctions haven’t made any difference to their violence,” he added. Abu Sharekh was referring to the financial sanctions the Biden administration placed on certain settlers and organizations following increased instances of attacks on Palestinian civilians. The sanctions did little to help: In 2024, the United Nations recorded the highest number of settler attacks in two decades.

The violence is not confined to rural areas, where settlers are armed farmers in illegal outposts. Settlers in East Jerusalem’s urban, developed neighborhoods have also been documented attacking and harassing Palestinian civilians. Sometimes, they are American.

“I hate to say it, but the American settlers are the most harsh, the most racist towards us,” Abu Diab, the activist from Al Bustan, told me.

“For example, so many of the settlers who took over houses in Sheikh Jarrah, in Silwan, in Batn al Halwa: you can immediately tell they are American from their accent,” Abu Diab said in a later interview in August 2025, “and some of them who commit violence against the Palestinian citizens also proudly say, ‘I am from New York, I am from California.”

In Zanuta, for instance, Yinon Levi, a settler Abu Sharekh had clashed with, raised $140,000 to support himself in response to American sanctions.

And now, even the flimsy guardrails set up by the Biden administration are gone. One of the first executive orders President Trump signed when entering office in January 2025 was to lift those sanctions, a decision warmly welcomed by Israel’s Finance Minister Bezalel Smotrich and far-right National Security Minister Itamar Ben-Gvir, two of the loudest defenders of settlements in the Israeli government. As it stands, Shakir said, the West Bank has already been annexed in practice, if not by formal declaration.

The cranes, at least, have never stopped. Givat Hamatos continues to expand, preparing to welcome thousands of new settlers, some of whom will be American citizens brought there by My Israel Home. The settlement is in the southeast end of Jerusalem, on a road that Palestinians from the West Bank can’t access. Just yards away, the Separation Wall locks Palestinian refugees out of lands they have inhabited for centuries. On the other side of the wall, just over a mile away, lies the Aida Refugee Camp, where thousands of Palestinians now live in overcrowded, crumbling cement buildings.

Recently, in the streets of Borough Park, Brooklyn, the battle over land sales has ignited new clashes. What began as a legal and political fight has now spilled into the realm of physical violence, with Zionist extremists assaulting pro-Palestine demonstrators. On February 18, members of the extremist Zionist group Betar US attacked several protesters, singling out anti-Zionist Orthodox rabbis.

“We just bought houses in Jenin,” Betar’s official account later boasted on X. “Fuck you, terrorist.”

For Palestinian activists, these violent confrontations in the US mirror the settler aggression their families face in the occupied territories.

“The NYPD has offices in the West Bank, they get tactical training in the occupied land, and they use those same tactics on us,” said Yasmeen, a Palestinian American woman who saw her friend punched in the face at that same protest.

Just a week after the Borough Park events, PAL-Awda countered a town council ordinance in Teaneck, New Jersey, attempting to take away activists’ constitutional right to protest. “Our demand letter led the town council to vote on hiring a constitutional lawyer instead of passing the ordinance,” Tova said.

Beyond the protests, the legal battle remains unresolved. Whether a Palestinian plaintiff will successfully challenge these real estate transactions in US courts is uncertain. But on the ground, in places like Al Khader, Zanuta, and Silwan, the consequences of these sales are painfully clear. Families like Abu Mohammed’s have already lost their land; Abu Sharekh must take the daily, now life-threatening, risk of grazing his sheep on land menaced by hostile colonists. Abu Diab continues to sleep beside the rubble of his home, refusing to leave.

A few miles away, Givat Hamatos grows—another brick laid, another road paved, another home on confiscated land waiting for an American buyer.

More from The Nation

How Taiwan Became the Chipmaker for the World How Taiwan Became the Chipmaker for the World

A new book tells the story of the island-nation’s transformation into a central hub for technological development and manufacturing.

This Is Not Solidarity. It Is Predation. This Is Not Solidarity. It Is Predation.

The Iranian people are caught between severe domestic repression and external powers that exploit their suffering.

How a French City Kept Its Soccer Team Working Class How a French City Kept Its Soccer Team Working Class

Olympique de Marseille shows that if fans organize, a team can fight racism, keep its matches affordable, and maintain a deep connection to the city.

Donald Trump’s Nuclear Delusions Donald Trump’s Nuclear Delusions

The president wants to resume nuclear testing. Senator Edward Markey asks, “Is he a warmonger or just an idiot?’

The Colonial Takeover of Venezuela Begins with Corporate Investment The Colonial Takeover of Venezuela Begins with Corporate Investment

The spectacle of Nicolás Maduro’s capture has drawn attention away from the quieter imposition of systems and power networks that constitute colonial rule.

The US’s Nuclear Arms Treaty With Russia Is About to Lapse. What Happens Next? The US’s Nuclear Arms Treaty With Russia Is About to Lapse. What Happens Next?

If the US abandons New START, say goodbye to that comfortable feeling we once enjoyed of relative freedom from an imminent nuclear holocaust.