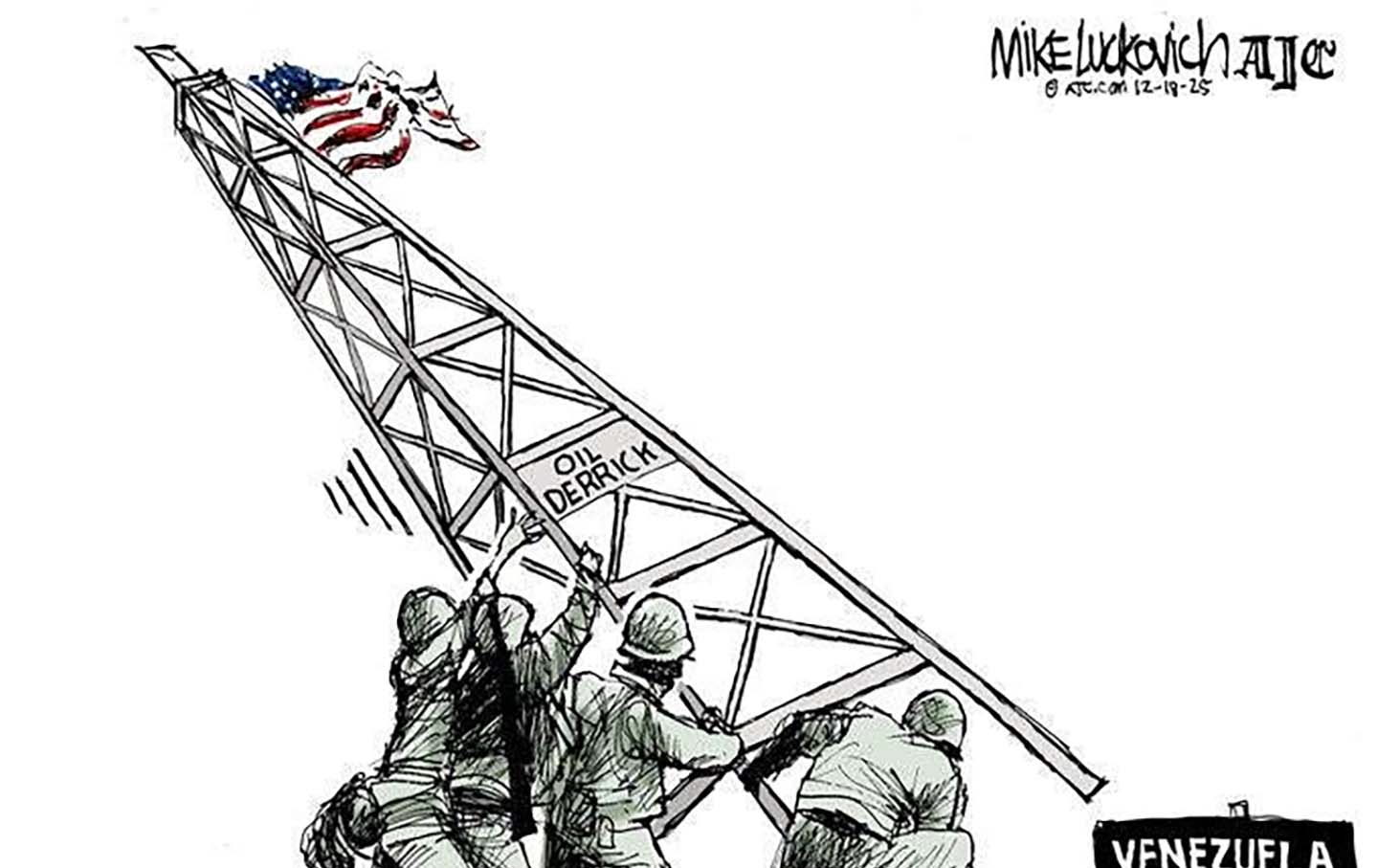

Tar Wars

Behind today’s headlines is a history of imperial outrage—including a Philadelphia contract man who wreaked havoc in early 20th century Venezuela and helped oust a president.

Before There Was Nicolás Maduro, There Was Cipriano Castro

Behind today’s headlines is a history of imperial outrage—including a Philadelphia contract man who wreaked havoc in early-20th-century Venezuela and helped oust a president.

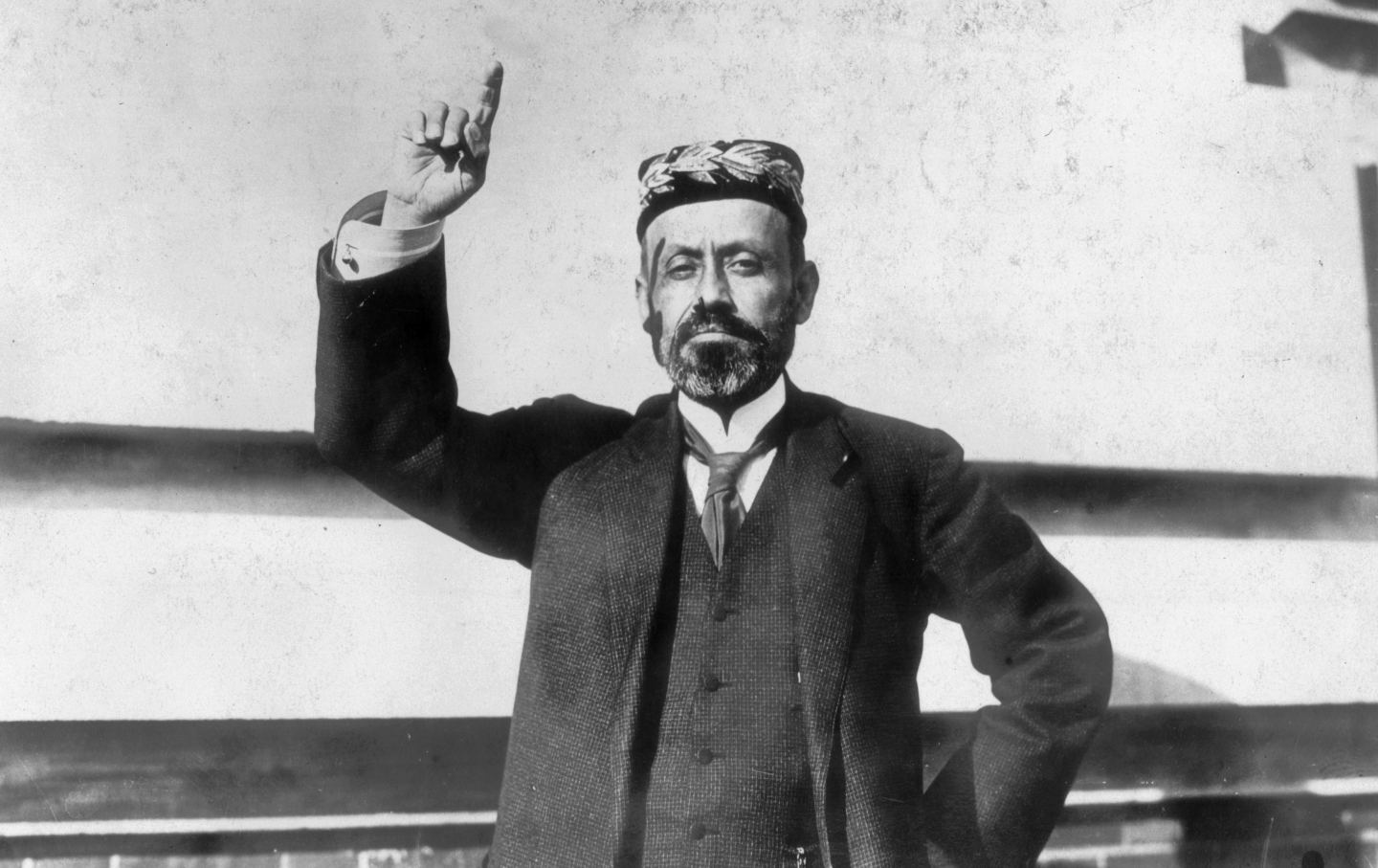

Cypriano Castro (1858–1924) was president of Venezuela from 1902 until he was deposed in 1908. He died in exile.

(Hulton Archive / Getty Images)Before Nicolás Maduro and Hugo Chávez, there was Cipriano Castro. Before Donald Trump, there was Theodore Roosevelt. And before petroleum, there was asphalt pitch. The following excerpt from America, América: A New History of the New World is a timely reminder that behind today’s headlines announcing any given crisis in Latin America often stands a long history of imperial outrages.

This excerpt illustrates one example of how domestic crisis in Latin America is often the result of actions taken by powerful outside actors, including politicians and financiers. Debt, poverty, war, and death in early-20th-century Venezuela were direct consequences of the machinations of Johnny Mack, a Philadelphia contract man connected to the highest ranks of the Republican Party. Mack used Venezuela to stage a war against his US rivals to establish a monopoly on asphalt, gaining control of a sputtering tar pit, which has been compared by more than a few to the gates of hell, near which no trees could grow nor birds fly. The conflict escalated, bringing to Venezuela’s shores Italian, British, US, and French gunboats, a face-off that previewed the coming global war. Mack’s asphalt war and Venezuela’s debt crisis had the effect of pushing Washington to accept some of the premises of international laws, if only reluctantly—a subject I go into greater detail in the book. Today, of course, US actions in Venezuela aren’t leading to a consolidation but an unraveling of international law and perhaps setting the stage for a greater conflagration to come.

—Greg Grandin

More than a decade before the New York–based Caribbean Petroleum Company sank the first oil well in Venezuela in 1914, a conflict over asphalt tar pitch provides a good snapshot of how the United States was compelled to accept some of the ideas of international law.

Asphalt was a vicious business in the United States, where corrupt machine politicians were handing out millions of municipal dollars to tar their city’s streets. Around this time, a well-capitalized gang led by John M. Mack, president of the Mack Paving Company, was making a bid to take control of the entire industry. The result was the creation of the National Asphalt Trust.

Mack was part of a group of Philadelphia businessmen collectively known as the Hog Combine, because they “hogged everything in sight.” A former bricklayer, Mack became a real-estate speculator and railroad financier. He controlled most of Philadelphia’s garbage trucks, headed up the city’s electric and telephone companies, and ran the trolley lines. Over the years, City Hall’s political bosses had given the Mack Paving Company some 4,000 contracts worth over $30 million. “My friends and I,” Mack later testified in a graft trial, “spent much money” to secure those contracts. With the National Asphalt Trust, Mack and his partners would attempt to secure control over all sources of asphalt coming into the United States, mostly from Mexico, Venezuela, Trinidad, and Cuba.

Mack’s intrigues caused havoc in Venezuela. The details of the sordid story are too many to relate here, but a sketch of the conflict is enough to convey its stakes. The fight was over control of Bermúdez Lake, an enormous pit in remote eastern Venezuela filled with thick, bubbling black pitch. The tar was heavy enough for the Spanish to use it to caulk their ships. A subsidy of Mack’s Asphalt Trust, New York & Bermudez Company, claimed the lake. So did rival companies. The trail of titles, deeds, and concessions, granted by previous Venezuelan presidents, reached back decades, and like Mack’s many contracts in Philadelphia, were often handed out in exchange for under-the-table money. Before long, hired thugs were fighting it out gangland style, battling for control of the tar lake like mobsters battling for control of a city’s gambling rackets.

A powerful Philadelphia party-machine Republican, Mack was better connected than his competitors. The tentacles of the Asphalt Trust reached to the highest levels of the United States government. Both Pennsylvania senators were investors, as was Assistant Secretary of State Francis Loomis.

US diplomats stationed in Venezuela not only held stocks in the Asphalt Trust but received direct payoffs from Mack’s men. Gen. Vinton Greene, the Asphalt Trust’s president, was close to President William McKinley, having overseen the finances of the US military government in the Philippines. Greene also was a former colleague of Vice President Theodore Roosevelt, from their days working on New York City’s police force.

So when Venezuela’s president, Cipriano Castro, refused to settle the dispute on the Asphalt Trust’s behalf, it was nothing for Mack to get the White House to send three battleships to cruise Venezuela’s coast in a show of support.

That was just a start. Mack and his allies then financed a Venezuelan banker and Castro rival, Manuel Antonio Matos, to launch a revolution against Castro. They paid to outfit a steamer, the Ban Righ, renamed Libertador, as a gunboat, and gave Matos another $140,000 in supplies and weapons, drawn from a Trust account earmarked for “government relations.”

Castro survived the revolt, though the uprising led to the deaths of thousands of Venezuelans and the destruction of much public infrastructure, including roads and ports.

Meanwhile, the State Department, working closely with Greene, pressed Castro to confirm the Asphalt Trust’s claim. Both Mack and his allies in the US government controlled the only English-language reporter in Venezuela, Albert Jaurett, himself an investor in the Asphalt Trust. All news that came out of the country, picked up by the world’s wire services, came from Jaurett. He hyped Matos’s revolution and smeared Castro’s government, generating panic among Venezuela’s creditors. The value of the nation’s currency collapsed. Venezuela’s debt soared.

The Trust’s war on Venezuela was taking place even as, next door in Colombia, Theodore Roosevelt, who became president after McKinley’s assassination, was pressing Bogotá to give up Panama. Roosevelt would soon dispatch war ships and land Marines at Colón, Panama, to make sure Bogotá couldn’t put down the provincial rebels. Most Panamanians didn’t know they were in the middle of a revolution for independence from Colombia until an “American officer raised” Panama’s “new flag.” The United States recognized an independent Panama in November 1903. Work began on the canal on May 4, 1905.

Back in Venezuela, Castro was tenacious in fighting what he called the “business invasion of foreigners,” the “invasions of the barbarians of Europe and the other America.” Castro’s government commandeered the Bermúdez pitch field and began shipping asphalt directly to Mack’s competitors. He also questioned the legality of the loans Venezuela owed, some of which dated back to before independence in the 1820s. He threatened to default on debt owed to both US and European creditors.

In response, Germany, Britain, and Italy, in late 1902, sent their own gunboats to Venezuela, sinking and seizing Venezuelan ships and bombing the coastline. Villages made up of mud huts and adobe houses were besieged by ironclad warships armed with state-of-the-art artillery, including cannons and mortars. The firepower was awesome, its effect terrifying. One of the causes of the soon-to-be world war was competition among European powers for overseas colonies. And so the Venezuela skirmish, made up of many future belligerents, can be seen as an augury of much worse to come.

Washington supported Europe’s demand that Caracas pay its debt. “You owe money,” a United States envoy told Castro, “and sooner or later you will have to pay.” But Washington didn’t want German or British naval vessels darting around the Caribbean.

Neither did Argentina want Europeans threatening Latin American nations over debt. Its foreign minister, Luis Drago, protested, urging the countries of the world to recognize the principle “that public debts cannot occasion armed intervention.” With its fast-growing economy, Argentina was challenging Washington for regional leadership.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →Roosevelt and Secretary of State Elihu Root sympathized with Drago, to a point—to the degree that Drago’s protest helped Washington limit Europe’s actions in the New World. But Roosevelt and Root rejected what became known as the Drago Doctrine, an absolute opposition to the use of military force to collect debts. Roosevelt was especially annoyed that Latin Americans were citing the Monroe Doctrine to argue that Europe couldn’t send its ships into hemispheric waters to force debt collection.

“If any South American country misbehaves toward any European country,” Roosevelt had declared earlier, when he was vice president, “let the European country spank it.”

Roosevelt wavered between deference to Europe on principle—“spank it”—and a sense that he had to act to check Berlin. Talk of war was constant in Washington. Anonymous sources told The New York Times that “persons of considerable importance in the War, State, and Navy Departments” believe that a confrontation with Germany was inevitable: “The war might as well come over Venezuela as over anything else” was the feeling of many in the Roosevelt White House; like measles, “it would be better to have the thing right away and be done with it.” War with Germany would come, but not yet, and would be sparked by a different set of immediate causes. Meanwhile, Venezuela simmered.

Roosevelt successfully pressured Rome and London to pull back. Berlin, though, ordered its gunboats to bomb Venezuelan forts, a defiance that had the side effect of drawing the United States and Great Britain closer to each other, setting the stage for its future world war alliance.

Roosevelt considered going into Venezuela himself. He ridiculed Castro, calling him an “unspeakable villainous little monkey.” The press painted the Venezuelan leader in extreme racist terms, creating a new standard of dehumanization of foreign leaders, especially leaders who threatened the property rights of foreign investors. The diplomat Francis Huntington Wilson, Yale educated, described another economic nationalist, Nicaragua’s president Joseì Santos Zelaya, as “unspeakable carrion.” Roosevelt thought Colombians “contemptible little creatures” for opposing his Panama grab.

From savages and barbarians to carrion and villainous monkeys, it seemed that modern capitalist property law had to arm itself with the worst images from the days when Europeans were debating whether Indians were humans or beasts, or some species in between.

Root was a restraining hand. Instead of having the United States join the assault on Venezuela, he brokered a deal to have all parties accept arbitration at the Hague.

Claims and counterclaims were many. Appeals went on for years. Arbiters mostly ruled against Venezuela. But Caracas won on several key points. One Hague judge affirmed the doctrine of sovereign equality, saying that all nations, despite their size or power, had the right to due and equal process. The judge went even further and said that behavior had no bearing on jurisdiction. That is, a large power couldn’t justify ignoring the rules of international law simply by pointing out the irresponsibility of its adversary.

Can it be inferred, the judge asked rhetorically, that only “civilized, orderly” nations are protected by international law? Should countries that are “revolutionary, nerveless, and of ill report” be relegated to “a lower international plane”?

Roosevelt and Root, if asked these questions, would have said yes, most definitely. London would have agreed. Civilization and barbarism. Virtue and vice. Solvency conferred sovereignty.

The Hague judge thought differently, saying that it was his “deliberate opinion” that all nations, regardless of comportment, enjoy “equality of position and equality of right.” The finding directly contradicted Roosevelt’s insistence that Venezuela was a pariah nation (and contradicts today’s consensus in the White House that the United States, not international courts, decides which world leaders are worthy of “equality of position and equality of right”).

The United States, Roosevelt said in December 1904—in what became known as his “corollary to the Monroe Doctrine”—would “exercise international police power” against “wrongdoing.” And it wouldn’t wait for a warrant issued by The Hague to do so.

In 1907, Venezuela’s high court fined Mack’s subsidiary, the New York & Bermudez Company, $5 million for damages incurred in the revolution that its parent company, the Asphalt Trust, had funded. Naturally, both the company and the State Department dismissed the court as corrupt and its ruling void. The Asphalt Trust toned down its confrontational rhetoric even as it began to support, more quietly, another armed movement against Castro. This time, Castro, sick from kidney disease and having no money in his treasury, couldn’t hold his political coalition together. He left Venezuela in December.

A new, more compliant government subordinated itself to Washington, and the Asphalt Trust had its claim certified.

An estimated 15,000 Venezuelans had lost their lives in that pointless uprising, financed by a Philadelphia contract man looking to control a sputtering tar pit. Soon the hunt would be for petroleum proper.

In other countries it would be other resources. Later, W.E.B. Du Bois, considering the causes of the coming world war, identified the rich world’s dependency on the poor world’s resources and labor: “Rubber, ivory, and palm-oil; tea, coffee, and cocoa; bananas, oranges, and other fruit; cotton, gold, and copper—they, and a hundred other things which dark and sweating bodies hand up to the white world from pits of slime, pay and pay well.”

More from The Nation

Cuba Hunkers Down as a US Oil Blockade Brings a Humanitarian Crisis Cuba Hunkers Down as a US Oil Blockade Brings a Humanitarian Crisis

Fear but no panic on the streets.

The Repeating History of US Intervention in Venezuela The Repeating History of US Intervention in Venezuela

A look back at The Nation’s 130 years of articles about Venezuela reveals that the more things change, the more they stay the same.

Trump’s Oily Attack on Venezuela Trump’s Oily Attack on Venezuela

The US government is seizing tankers like pirates.

Report From the Progressive International’s Nuestra América Summit Report From the Progressive International’s Nuestra América Summit

Colombia holds its breath as President Gustavo Petro heads to DC.

Cuba Rallies Residents, Prepares for War Cuba Rallies Residents, Prepares for War

As Washington escalates regime-change pressure after the Venezuela raid, Cuba braces for confrontation amid economic collapse, oil shortages, and mass mobilization.