A Trip Through Hell

In a Washington county jail, solitary confinement is the worst, most degrading, foulest experience you could ever imagine.

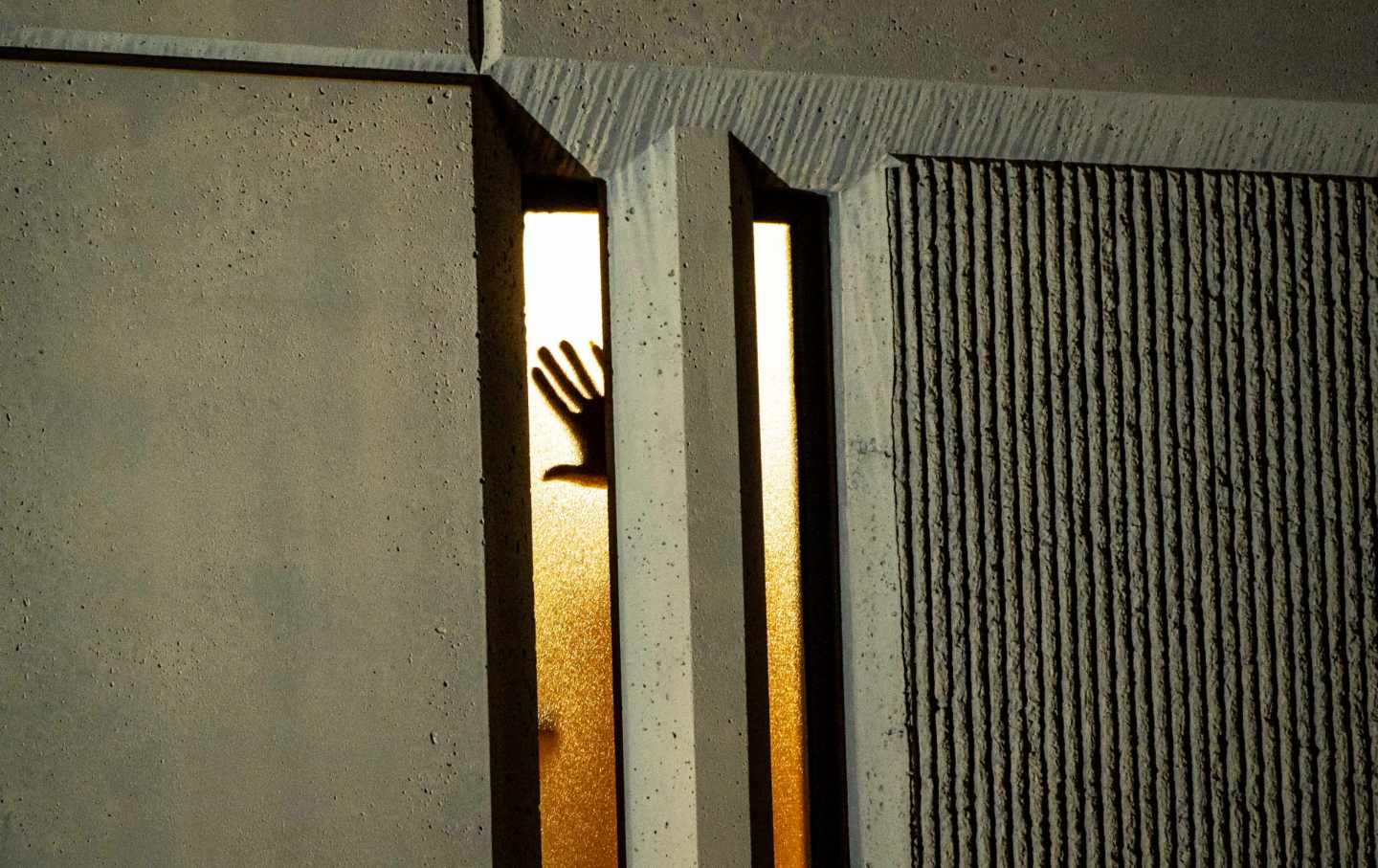

A person places their hand on a window inside a jail as demonstrators make noise outside during an anti-police protest on January 24, 2021, in Tacoma, Washington.

(David Ryder / Getty Images)In 2022, I had been in prison for nearly two decades. I had another two decades left on my sentence for robbery and murder. While I had spent my first eight years in prison mired in the same bad attitude and mindset that got me “sent up” to begin with, I had devoted the next 11 years to educating myself, learning about restorative justice, and becoming the kind of man who would never make the choices I did as a teenager. In 2021, in Washington State, the Blake ruling gave hundreds of incarcerated people the opportunity to receive a second look at their sentence. I was one of them. After almost a decade of fighting to find a way back home through the courts, I was finally getting a chance.

My gratitude and excitement were only dampened by the knowledge that to be able to plead my case in a resentencing hearing, I’d have to go through Hell—otherwise known as Pierce County Jail, in downtown Tacoma, Washington—again. Pierce, also known as “County,” is somewhere I had spent a good deal of time before being sentenced to prison. And County is a place where the horror stories never end.

My court date was set for December 16, 2022, and I expected to be transferred on December 13, but for some reason, on December 5 at 10:32 pm, a prison guard approached my cell and said, “Pack all your property, Mr. Blackwell, you’re being transferred at 4 am.”

The transfer process began with a small meal, but I didn’t eat it. I did not want to need the toilet on the journey. The toilets were in the back of the bus, no door or privacy of any form, a prison guard a mere two feet away, and other prisoners not that much further.

After I gave my meal to another prisoner who was also being transferred, we were taken to a cage where we were strip-searched. We removed every piece of our clothing, and every crevice of our body was inspected for contraband. Rarely is anything found in this process, but it strips prisoners of their clothes and dignity, a frequent goal of the carceral system. After the humiliating experience, we were tightly bound in chains at our waists, ankles, and wrists, and dressed in orange jumpsuits with no undergarments or other clothes. The shining steel bit hard into our soft skin.

One by one, we took the long walk to be loaded onto the bus—each step short and painful as the shackles rubbed into our ankles and slowly began to cut into the skin. It was a cold winter morning. My feet, without socks in rubber slides, traveled haltingly across the snow-covered ground. Once we were counted, the bus fired up its loud engine and we slowly pulled off.

Throughout the ride, guys were talking about what awaited us. The stress of having to go back to County was unmistakable. All of us had been there before. We knew it was rife with gangs and violence. The last thing I needed was to attend my resentencing hearing with marks on my face from a fight. A situation that wasn’t always avoidable in County.

“Get ready! We are on our way to Gladiator school!” One of the prisoners said, with a nervous look in his eyes.

He was met with unsettled laughs.

We arrived at the jail and were taken to the booking room. The building smelled of stale air and chemicals. A flood of memories reminded me of the last time I was here—the day I was arrested all those years ago. The one that hit hardest was me, sitting right in this room, more than 20 years ago, knowing I had taken a human life. The trajectory of his life, those connected to him and my life and everyone connected to me would begin to fall like dominoes on an unwanted path created through my greed and negligence. Being the man I had become, I was able to recognize and think through my greed and negligence. Knowing now what I didn’t know then made the memory even more difficult. Twenty twenty-two me was feeling the harm I had caused as if it had just happened. But I guess that is my responsibility and that of anyone who takes another life from this world.

The chains that bound us were removed, and my ankles instantly felt relieved. We were each taken to a desk, and a series of questions was rapidly fired off.

“Are you suicidal?”

“Do you feel sick?”

“Are you on any medicine?”

“When was the last time you drank alcohol or used drugs?”

This went on for about 20 minutes. Once the questions were done, I was again taken to a room and told to remove all my clothing, stripped of my clothes and dignity yet again. When this process was complete, I was given pink socks, boxers, and a T-shirt and taken to be fingerprinted and photographed.

Exhausted, I asked how much longer until I could use a phone, and inquired as to where I would be housed in the jail.

“You’ll get a call soon, and you’ll be going to 3-South in the old jail,” the guard replied.

I tried to protest, but it did no good. 3-South is the last place I wanted to be. It is a solitary confinement unit that’s mostly used for prisoners held under suicide watch. The guard said I had to go there for observation because of the severity of my charge—Murder 1—regardless of the fact that it happened almost two decades before, and I was only in County to be resentenced.

While I was waiting to be escorted to my new dungeon, the guard asked if I was ready to make a phone call. I jumped at the chance. All I wanted to do was tell my wife what was going on and go to sleep. I had been awake for over 24 hours.

The sound of her voice was blissful and comforting. We talked through all that was happening and worked to assure each other that everything would be OK. This was exactly what we had been working toward—my getting resentenced. Thankfully, I was left to use the phone for about an hour. We treasured every minute, knowing it would be rare to receive this kind of time on the phone while I was there. And even though our house is five minutes from the jail, there would be no in-person visits.

When a guard came to collect me, I was again cuffed tightly and taken to solitary confinement.

I struggled with the logic of my placement. I was being taken to isolation for no other reason than the crime I committed almost 20 years ago. I asked the guard to reconsider. I knew all too well the horrendous experience I was in for, and would do anything to avoid it. The guard, in a dry, drone-like voice, told me there was nothing he or I could do about it.

We walked the rest of the way in silence. I fought to calm the anger burning inside me, and I continued to remind myself that I knew this was exactly what a trip to County would be. I also knew it would be worth it in the end.

We arrived at the cell, where another guard approached us. He had a harsh voice and a cold demeanor. My guess was this is how he survived working in a place like this. He placed me in the cell, opened the slot on the door, and told me to place my hands through it so he could remove my handcuffs. I complied, ready to have the cold steel removed from my skin. Before he could walk away, I swiftly scanned the cell for any necessities I might need—toilet paper, a book, hand soap, a drinking cup, and writing material. I had done solitary so many times for so many reasons, and I knew if I didn’t receive these items right away, it might take hours or days to get them, if I got them at all.

I noticed there were none of these items in the cell. I knocked on the thick glass window and asked the guard for them. “I’ll get around to it. Right now I’m busy,” he said.

As he walked away, I heard him flick a switch, and a bright fluorescent light filled the cell. I yelled through the crack of the steel door that I didn’t need the light. “That light stays on for your safety,” he quickly replied. I walked away from the door feeling tired, frustrated, and defeated.

The cell was filthy. I didn’t even want to sit on the thin pad of a mattress until I could clean it with some disinfectant. A couple of hours passed before the guard returned with a single roll of one-ply toilet paper. He opened the slot on my door and dropped the roll on the floor. I rushed to catch him before he left. I asked him about the other necessities I requested and for some cleaning supplies. “I’ll look into it,” he replied again. He never returned.

I was exhausted and had been awake for over 30 hours at this point. I noticed in disgusting detail how badly the cell needed to be cleaned. I could feel my slides sticking to the floor. The walls had what looked to be food and other bodily fluids smeared all over them. Even the steel sink and toilet had God only knows what all over them. I felt extremely overwhelmed. I wanted to clean the cell, shower, and go to sleep.

I couldn’t stay awake any longer. I made my bed—the mattress a mere two inches thick—with blankets and sheets that were tattered, worn, and covered with holes and stains. There was no pillow, so I folded up one of the two small blankets. The second my hip touched the mattress, I could feel the hard concrete beneath it. I removed my T-shirt and wrapped it around my head to block the bright light. I curled up into a ball and thought about my wife. I quickly fell asleep.

Clank! Clank! Clank!

I woke up to a guard rapping on the steel door—loudly —with his metal key.

“Hey, you want chow or what?” He asked. It was 8 am.

I stumbled to the door, half asleep, and grabbed the styrofoam clamshell tray through the thin metal slot in the door. I opened the tray of food and immediately noticed I had no eating utensil. I knocked on the window. “Guard! I need a spoon, I didn’t get one!” I yelled through the thick door.

He appeared seconds later. “You see that thick piece of paper? Fold that up and use it as a spoon. You’re on the suicide unit; we don’t hand out such things. It’s for your own safety.”

Angry, I quickly shot back: “I never told anyone I was suicidal, so why the fuck am I on this unit?”

Frustrated, I took a couple of deep breaths to try to recalibrate myself. I took the piece of paper and folded it to scoop the food from the tray. The meal was bland and tasteless, a mush-like texture. I ate about half of it and decided to go back to sleep.

Bang! Bang! Bang! Bang! This time, I was woken up by another prisoner on the unit kicking his door. He was kicking it with such force I could feel it through the concrete slab on which I lay. Close by, I heard a mental health staff member trying to reason with the struggling prisoner, but he was hearing none of it.

I slowly drifted off again, but only briefly because there was a commotion outside my cell. A prisoner, who appeared to be young and scared, was handcuffed and being escorted by five guards. The guards were laughing and mocking the young prisoner. A green suicide gown, like a hospital gown, was draped over his chunky body, exposing naked parts of his flesh.

Once he was in his cell, the prisoner told one of the guards, “I love you.” The guard quickly replied, “I love you, too,” half-mocking. I didn’t understand the exchange at all, but it was clear the kid wasn’t in his right state of mind. The female guard next to her partner said, “Did he just say he fucking loves you?” With a smirk on her face. “Yep,” he replied. They both walked off laughing as the slot was slammed on the prisoner, isolating him from everyone but himself.

The prisoner who was previously banging on his door started up again. It went on for hours. I could feel a headache coming on. It’s hard to say if it was from the lack of caffeine—in prison, I drink seven cups of coffee a day, but in County I’ll have none—or from the banging that was taking place.

Dinner was served around 4 pm, and I was starving. I hadn’t had an edible meal yet. This one was no different. I had no clue what it was. I forced myself to try some of it, but I decided I’d rather go without than eat whatever that was. Aside from the small portion of vegetables, the rest of the meal seemed to be a mystery. There was a small oval-sized pressed meat patty that tasted like chemicals when I took a small nibble. I couldn’t place what it was, so I left it. I quickly ate the vegetables, which were no more than a few small bits, overcooked and mushy. Then there was an ice cream–sized scoop of something that looked to be noodles, which had been cooked to the point of resembling mashed potatoes. There was no sauce on them; they were plain and bland. I left it all and decided I would take my chances with the breakfast meal.

At around 8 pm, I finally decided I’d had enough with how filthy this cell was. I banged on the window of the door and called for the guard. When he arrived, I explained my situation to him and pleaded with him for supplies to clean the cell. He looked through the thick glass on the door and said, “Yeah, it’s pretty bad in there. Let me see what I can find.”

Minutes later, he returned with a spray bottle and some rags that looked to be torn-up T-shirts. He told me it was all he could find, and I thanked him.

I started from as high as I could reach on the walls and worked my way to the floor. After several handfuls of rags, two spray bottles worth of cleaning solution, and two hours of my time, the cell was finally clean. I stood there tired and covered in sweat. It felt so much better to know that I could now touch a surface without an unknown bodily fluid touching me. But then I needed a shower.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →I knocked on the window and asked the guard if I could get a quick shower. He told me that wasn’t possible. Frustrated, I kept my cool and asked if I could have a bar of soap, some clean clothes, and a couple of towels. He agreed. It was time to take a bird bath. I’d been forced to do that many times in solitary confinement throughout my years in incarceration. I stripped down to nothing and stood over the open toilet, as I soaped up with my tiny domino-sized bar of soap and poured small cups of water over me from the sink. I tried to catch most of the water in the toilet, but no matter how hard you try, this process often leaves a large puddle on the floor.

Finally, at around 11 pm, the cell was clean, and so was I. I felt relieved.

What hadn’t subsided was the banging from the nearby prisoner. I continued to feel the vibrations from his anger with each kick. Exhausted, I lay down and tried to sleep. As I fell off to sleep, I told myself, “Only 10 more days, and then you’ll get resentenced. That will make all of this worth it.” The thought of a second chance to make better choices and contribute to my community made me smile.

I tossed and turned in a restless sleep. Guards laughed and talked loudly with each other. Walkie-talkies crackled to life every few minutes. Prisoners yelled and banged on their doors. The bright fluorescent light never shut off. With the unforgiving concrete on which I was forced to sleep, it was all too much. Sleeping for more than a few minutes was impossible.

Around 4 am, the thin slot on my door popped open with a loud bang as it swung down and smacked the steel door it was attached to. A guard’s raspy voice asked, “You want breakfast?”

I stumbled to the door, starving and hoping this meal was better. Breakfast usually is in places like this—it’s hard to mess up oatmeal and eggs. Shockingly, the breakfast was equally as bad as the dinner the night before. The eggs looked odd—watery and undercooked. The oatmeal was a blob of mush that had been overcooked and had been sitting long enough to fuse into a hard ball of slop. Then there were two tiny round meat circles that tasted like chemicals and fake sausage. I stomached what I could and left the rest.

Within minutes, the prisoner who was banging on his door the night before started up again, obviously still angry about the day before. My headaches continued to get worse, coming in waves. I paced the room for hours, drowsy and exhausted. My body ached and my mind was consumed with thoughts of missing my wife and the stress of my upcoming resentencing. So much was on the line. If my resentencing didn’t go well, I’d have 19 years left to do in prison.

I paced until lunch was served. The guard told me it was 9:41 am. The meal was a pressed meat patty of some form. I tried to eat it, but it tasted like it was marinated in Windex. I’d rather be hungry than eat that. I started to pace again. If I walked at just the right angle, I could get four steps in before I was forced to turn around.

“You want a shower and to use the phone?” a guard at my cell window asked.

I jumped at the opportunity. After over 30 hours in solitary, I was finally able to shower and call my wife.

“You have one hour to shower and use the phone, no exceptions. So use the time how you want,” the guard said.

The tiny steel-walled shower was dirty and had dozens of little white domino-sized half-used bars of soap scattered throughout it. The water shot out in a small cone-like mist, making it hard to wash the soap off. I had to cup the nozzle with my hand to force the water into a thin stream. I hurried so I could have as much time as possible to talk to my wife.

When I finished my shower, I asked the guard for some clean clothes.

“Looks like you’re standing on them,” he said as he looked my naked body up and down. I was using my old clothes to keep from standing on the bare, filthy floor, and he was referring to them.

“I thought we got new clothes after a shower,” I said in a pleading voice.

“I’ll make an exception this time,” he said. “But next time, you need to remember we only hand out clean clothes twice a week. Next time you’ll have to wear the ones you’re standing on.”

I didn’t reply. I knew if I did, my anger would spill out all over this guard. And I’d gain nothing from it. Self-control is just one thing I had to teach myself over the years of my incarceration.

After the guard arrived with my new set of clothes, I was handcuffed and taken to the phone at the end of the hall. When we got there, I expected the guard to remove the handcuffs, but instead, he ran a chain by the phone through them. I looked at him, confused. “Sorry, you have to be chained to the wall to use the phone,” the guard said. I brushed it off. What choice did I have?

Struggling to dial the numbers on the phone, I finally managed to get through. Once I heard my wife’s voice, I forgot about everything that had been going on and got lost in the conversation with my best friend and partner. We talked until the guard came to collect me.

After the call, I was returned to my cell quickly. The prisoner next to me started to bang again, and I was removed from the joy of my call and returned to my environment.

It went on like this for eight days, and then, just two days before the scheduled date of my resentencing hearing, the hearing was postponed, thanks to a maneuver by the prosecutor. I was returned to prison without my day in court.

The entire journey to Hell was for nothing.

The stress and anxiety I went through and put my wife and supporters through was for nought. The countless hours of preparation that my legal team and my community went through: wasted. My return to a place where I hadn’t been in 20 years and a place I never want to be in again was just like the cavity search I suffered on each leg of the journey: not useful to anyone and destructive to everyone, especially me.

When I finally did get a hearing three months later, the prosecutor who had dragged everything out admitted I was rehabilitated, but refused to exercise the opportunity of the hearing to reduce my excessive sentence.

All of these things happened to me years ago, but these things are happening to people every day. Conditions in places like county jails continue to decline. People are being forced to survive conditions that are borderline unlivable and torturous while fighting to receive a fair outcome through the criminal legal system. The majority of the people in county jails have yet to be convicted of a crime, so why are we, as a society, allowing our citizens to be treated this way?

My story is just one story of many, and sadly, it’s not unique. It’s just another moment of the system functioning exactly as it is meant to.

More from The Nation

The Endless Hypocrisy of Bari Weiss The Endless Hypocrisy of Bari Weiss

She claims to be a free speech champion. But as her actions at CBS News keep showing, she seems to think free speech should run only in a rightward direction.

What Will Be Left After the University of Texas Destroys Itself? What Will Be Left After the University of Texas Destroys Itself?

UT-Austin has collapsed its race, ethnic, and gender studies into a single program while a new policy asks faculty to avoid “controversial” topics. But the attacks won’t end there...

The Corporate Media Is Head Over Heels for the Iran War The Corporate Media Is Head Over Heels for the Iran War

Donald Trump’s attack may be surreal, unjustified, and illegal. But that’s not stopping the press from turning the propaganda dial way up.

The Disturbing History of ICE’s “Death Cards” The Disturbing History of ICE’s “Death Cards”

The Vietnam-era practice is yet another example of ICE agents thrilling to the brutality they have been encouraged to cultivate.

The American Universities Programming Israel’s Killer Drones The American Universities Programming Israel’s Killer Drones

Industry partnerships in higher education are pushing STEM graduates into the business of weapons manufacturing and genocide profiteering.

The Red State–Blue State Healthcare Divide Is Dangerous for Everyone The Red State–Blue State Healthcare Divide Is Dangerous for Everyone

Whether or not you have access to independent, scientifically sound public health guidance may depend on how your state voted for governor.