What Justice on a Burning Planet?

Andreas Malm and Thea Riofrancos joined The Nation’s Wen Stephenson in an urgent conversation about the left and the climate emergency.

On December 19, Haymarket Books and Verso Books cosponsored a conversation about the left and the climate emergency, hosted by The Nation’s climate-justice correspondent, Wen Stephenson. In his introductory remarks, Stephenson drew on his recent Nation essay in which he quoted the “State of the Climate Report” for 2025, and made the following observation:

It’s no stretch, at this late date, to conclude that nothing short of revolution, in some form, will be required to salvage progressive visions of a better world. It should be obvious—and always should have been obvious—that climate activists, a mere climate movement, can’t do this alone. What’s required, and always has been, is not simply a broader, better organized, more powerful “climate left”; what’s required is a far more powerful left—a resurgent, revolutionary left—a movement of movements, a popular front in which the total defeat of fascism and of fossil capital are understood as inseparable.

Joining Stephenson in conversation were Andreas Malm, associate professor of human ecology at Lund University, whose latest book, co-authored with Wim Carton, is The Long Heat: Climate Politics When It’s Too Late; and Thea Riofrancos, associate professor of political science at Providence College, whose latest book is Extraction: The Frontiers of Green Capitalism. The following are excerpts from the event.

Wen Stephenson: My broad opening question is this: Given the state of both climate science and global politics, is it still possible to imagine something like global justice, the historic project of the left? What kind of justice is still possible? Feel free to take issue with the question itself. Is it the right question?

Thea Riofrancos: I think it is a good question, but I think the framing might be a bit misleading, in the sense that both global justice and global solidarity—which are not the same thing but are connected to one another—are relational and relative concepts. Power relations are dynamic. We can have improvements in the balance of forces from a left perspective, and we can have defeats, and those defeats might be provisional.

More directly, if it’s the case—which the climate science continues to show—that every fraction of a degree of warming continues to matter, then every effort oriented towards the horizon of combating and transforming fossil capitalism also matters. That does not mean—and I want to be really clear about this—that we can’t distinguish between moments of defeat and moments of, again, always relative victory.

A few years ago, I felt—political optimism is probably too strong a word—but I saw many more openings in the terrain for specifically left climate politics than I would, in all honesty, see in this particular moment. We can compare conjunctures. We can be honest about defeats and victories. We also need to be ruthless—though in a comradely fashion, hopefully—in our analysis of what tactics work, what strategies work, and be really honest about the state of scientific findings about how dire the situation is.

But I think the question of how to combat and transform fossil capitalism—I mean, we need to defeat and dismantle, but we also need to build something in the wreckage that is a saner economic system and relationship between humans and nature. So the task of combating and of transforming is more urgent and more enigmatic than ever. We are firmly in what Andreas and Wim call the “overshoot conjuncture.” And it’s actually unclear in a political sense, from left principles, how exactly we’re going to combat not just fossil capitalism in general but also the kind of deadly silence and denial that creates a veil around the climate crisis itself and makes it hard to directly address.

I would just say, with the risk of being a little provocative, that this relative silence, and what we could even call forms of soft denialism, are pervasive on the left, including with people I work with and organizations I work with.

I think there’s a real, urgent task of reconnecting the left to the climate crisis. And that itself is an internal battle within the left—or battle is maybe too antagonistic a term—because we’re going to need to persuade and agitate among our own political movements to refocus on this issue that has been unfortunately quite lost again, including on the left.

The human impacts are piling up, the catastrophes are piling up around us. And here in the US, fossil fascism has seized political power. But I also want to bring in the fact that the so-called center-left pundits and politicians are doubling down on climate denialism. We’ve had op-eds, for example by Matt Yglesias, saying Democrats should embrace oil and gas. And recently we had a Democratic lawmaker in Congress [Senator Ruben Gallego from Arizona] release his big energy plan, which also calls for doubling down on oil and gas. I mean, this is the center-left, let alone the right.

But as these centrist and fascist forces deny and deflect and double down on fossil fuels, the left is not centering this in our organizing or our movements.

Here in the US, the reality is particularly stark. The US is a kind of epicenter of tech, fossil-fuel, oligarchic reaction that has increasingly consolidated and is shifting electoral outcomes around the world.

And so the crux of the question remains under what conditions could we expect to see the formation of a mass, globally interconnected movement of a self-consciously climate character that directly targets all the nodes in the global supply chains—whether extraction, logistics, finance—of global fossil capitalism while also programmatically building towards what we might call our desired social form, whether we want to call it green social democracy, eco-socialism, carbon-free communism, or whatever we want to name as our vision for that horizon.

Should we stay committed to the emergence of an explicitly climate movement, that has a specific target on fossil capitalism, versus other types of left movements and grassroots and popular struggles that are more indirect yet take aim at the same kind of global system very broadly construed?

Andreas Malm: For an answer to the event’s framing question, “What justice on a burning planet?,” basically the answer must be none. Because the planet is burning through injustice, in the sense that the people that are caught in the fires are not the ones that have poured fuel on them. And the people who get richer by the day by pouring fuel on this fire can so far stay at a distance from the harm and the damage and the suffering.

I don’t know of any better and more precise picture of this injustice than the scenes that we have seen playing out in Gaza over the past weeks, where hundreds of thousands of people that have managed to cling to life during this genocide have been struck by the blow of extreme flooding from storms. Children die, and people have their lives destroyed for what, is it the 10th time? The 100th time? There are so many layers of compounded injustice that come together at the beach in Gaza that it’s hard to wrap one’s head around it.

I think the moment that we’re in right now is particularly stark for those of us who’ve been committed to two major mobilizations in the past decade, namely the climate movement and the Palestine movement. Because right now we’re in a situation where the climate movement is a shadow of its former self in the Global North. As for Palestine, we’ve had the largest Palestine mobilizations in history since the beginning of the genocide. But what happened after the announcement of the so-called ceasefire is that the Palestine issue, just like the climate issue, plunged to the bottom of the agenda, and the ongoing destruction of the Palestinian people in Gaza and the West Bank has become completely normalized as background noise that no one really cares much about anymore. This is the central effect of the ceasefire.

And it’s very similar to the situation with the climate, that there is this general structural, systemic mode of denial where we walk into it with our eyes wide open and at the same time totally closed.

And the normalization of these two analogous, or maybe even homologous, catastrophes, I think, is now coming in the shape of this start-up that you might have heard of called Stardust Solutions. It’s a direct offshoot of the military technological industry in the State of Israel that is developing a technological solution for solar radiation management, which this company is very actively promoting and lobbying for in the US Congress. And in the latest reports they claim that they will have this technological solution ready for deployment in 2030.

Many of us who have worked on climate politics for some time have had this feeling that geoengineering is a very likely outcome. It feels almost inevitable, because it looks so easy to do, relatively speaking, compared to abolishing fossil capital. Geoengineering goes perfectly along with the class interests of the most reactionary factions of the capitalist class.

And just the other day, Elon Musk tweeted that he wants to combine solar radiation management with some kind of AI robot. So you will have AI technology in charge of running SRM in the stratosphere.

The void, the absence of any major pushback against this drift into solar geoengineering is extremely disconcerting.

So far, with very few exceptions—and maybe the main one is Colombia, and we can get back to that—it’s extremely difficult to see the ongoing climate suffering in the Global South developing into a climate subjectivity, as in, people rising up against fossil capital. It’s just not happening. And I wish that we could bet on it starting to happen at some point. You know, “If only things get bad enough, then people will wake up.” But I don’t think we can count on it.

TR: I don’t disagree with anything you said, but I want to restate my question, as to whether we can view the emergence of a climate subjectivity or a climate left that’s more directly, self-consciously identified as such, in the absence of a broader change in left forces or the balance of power.

I think that the task of building a climate movement is part and parcel of the task of building left political power and social power and organized working-class power more broadly.

You brought in Colombia, and I did want to talk about these politics in Latin America. Because there are few places on Earth where we can see sustained resistance to extraction, including very much oil and gas and coal.

It’s precisely in Latin America—and the Colombian government is evidence of this—where we’ve seen some of the most vanguard types of resistance and policy initiatives that make declarations, in legal form, like we’re not going to lease any more fossil-fuel projects. That’s the [Gustavo Petro] government’s policy, and they’ve sustained that policy, which is quite impressive given the weight of fossil fuels in their political economy.

But we could also go to Ecuador, where there have been legal victories in declaring whole swaths of the Amazon off [limits] for extraction, or where you need really rigorous forms of consent of Indigenous communities there in order to move any project forward, in which the rights of nature are being actually protected in some ways.

And so, can we imagine a climate left without a more muscular, militant, well-organized left in general, which would necessarily have multiple domains of struggle and conflict? And what do we do about the fact that we see the most progress in resisting extractive projects, including fossil fuels, in ways that are relatively delinked from the climate crisis, at least rhetorically?

AM: Yeah, I would love to continue this conversation because you, unlike me, have a deep knowledge of Latin American environmental politics.

But let me start with something that you said, namely, should we envision a climate movement that does a lot of other stuff than climate politics, or should we aim for a narrowly defined climate movement? This is a dilemma that what’s left of a movement in Europe has grappled with since the peak of 2018–19. And the general drift has been towards a diversification, but also a fragmentation, of climate activism. And the person who embodies this drift is [Greta Thunberg] herself, who nowadays is almost more like a Palestine activist or a decolonial activist than a climate activist. Her vision of climate politics has been that it’s impossible to distinguish or separate from all these other struggles.

But then you will meet comrades in the remainders of the climate movement who will say that we’re all on board with this, but the problem is that we feel that we lose our identity as climate activists, and that it becomes unclear to people what the climate movement is and where the climate agenda is, because it gets lost in all these other struggles.

This is a genuinely difficult dilemma, and I think that one of the things that is so impressive—to jump to a completely different political context, in Colombia—is that Petro has really managed to embed a very explicit climate rhetoric in social environmental struggles in Colombia that have other sources than anger. I don’t think we should underestimate the importance of Petro’s rhetoric throughout these four years that he has been in power, where he’s been very consistent about the climate issue motivating his moratorium on any new fossil fuel installations. Not only has he spread the awareness of the climate issue in Colombian society, as far as I can tell, but it’s also been essential for maintaining some kind of hope in the [global] struggle for a fossil fuel phaseout.

We’re looking at this conference—the world’s first international conference about phasing out fossil fuels—that I hope people know will take place in Colombia in April. This is together with the Fossil Fuel Non-Proliferation Treaty, and it’s a beacon of hope in the dark. And it’s not by chance that this beacon comes from the Global South, and it’s not by chance that it comes from Latin America, because Latin America is the only part of the world where the left retains a capacity to win state power.

And this is really the crux of the matter. Everything that’s been achieved in Colombia over the past four years is a function of the fact that the left won executive power and that you have such a unique president as Gustavo Petro in the presidential palace in Bogotá. This makes all the difference.

TR: I want to underscore a couple of things that you said which did provide some interesting answers to my questions.

One is, it is impossible to imagine concrete, material, and durable climate victories outside of the context of left political power. In the case of Colombia, and despite the current Colombian government not being able to achieve a lot of its goals, I’ve been pleasantly surprised that we’re seeing continued popularity for the project. I think that the project of the political party that’s now formed is becoming more durable than the one leader, which is very important.

There’s been longer-term processes in Colombia, for example, building popular consciousness even among fossil fuel workers to embrace their own version of a just transition. The Colombian labor movement really stands out for explicitly talking about phasing out their own industries.

So there’s a longer social process, and the way in which historically there’s also been interesting connections between environmental justice and coal worker agitating in Colombia that has, I think, created a more eco-social imaginary. And I think that gives us insight into the breadth of social forces that are necessary and the multiple terrains of this type of climate struggle.

WS: I want to move to another question, which is, what do you see as the prospects for building a truly mass movement that does have revolution in some form, even if merely the political, as its explicit goal—and that has radical decarbonization and climate justice explicitly as a core pillar? Where do you see the potential for a revolutionary subject in this picture?

AM: This is the big question. I think the moment we’re in is one of permanent catastrophe, in the sense that one disaster after another is being thrown at us. And this is a symptom of the historical defeat of the left. But what that also means is that things are going to break down, and we don’t know when this will create openings for us. The system is so victorious that it keeps destroying everything, but this can eventually at some point curve back on the system itself, so that it becomes self-destructive. At a certain point, the amount of wars and climate disasters and whipped-up tendencies of fascism will create fractures and cracks in the ruling order itself, perhaps.

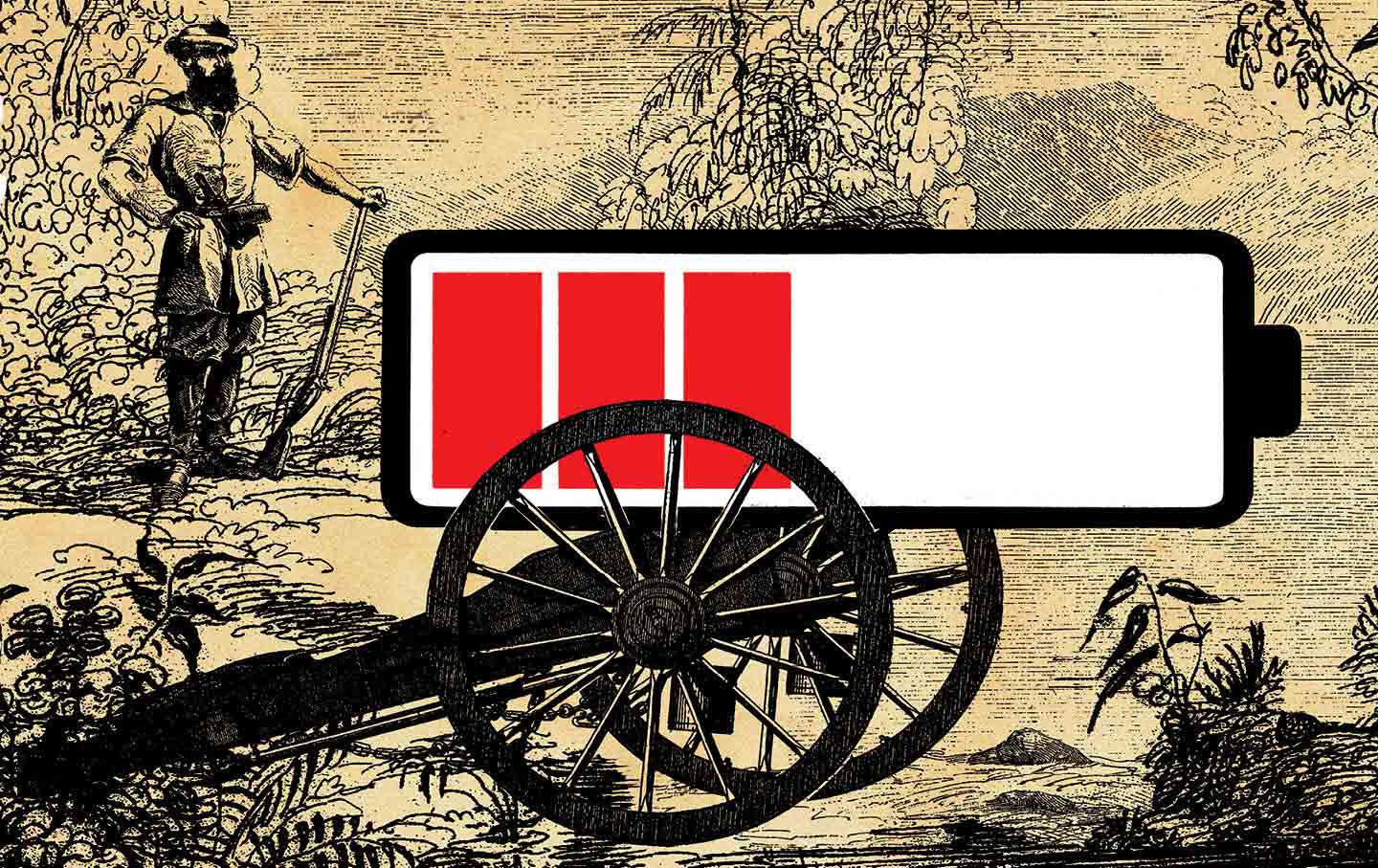

This is the original Leninist wager. When you have a system that compulsively generates catastrophe—the original case being the First World War—then the task of the communists is to seize the moment of disaster and transform it into a revolutionary crisis for the system. We don’t know when, or if, the opportunity comes. So being a Bolshevik is lying in ambush. You’re waiting for the right moment, and when it comes, you seize it. This is the fundamental lesson that is still applicable from the Leninist tradition, I think.

But it also leaves us in a certain kind of blindness, because we can’t really see where the target is or know that it will ever show up.

The immediate task, then, for climate activists is to be real Leninists, in the sense of saying to people that this is a crisis of the symptoms, but if we don’t want to drown in these symptoms then there’s no other logical possibility than to turn this into a crisis of the driver—the cause—to focus on what is pushing us into this ever increasing spiral of catastrophe. And this is the fossil fuel companies to begin with.

This is the immediate short-term task—to resurrect something like a climate movement to strike when it’s hot, when actual climate disasters are taking place, and to make the point to people that if you don’t like this, and if you don’t want this future, then what you have to do is go after the drivers and shut them down. We haven’t seen that yet, but it has to happen at some point, otherwise we’re doomed by definition.