What Happened

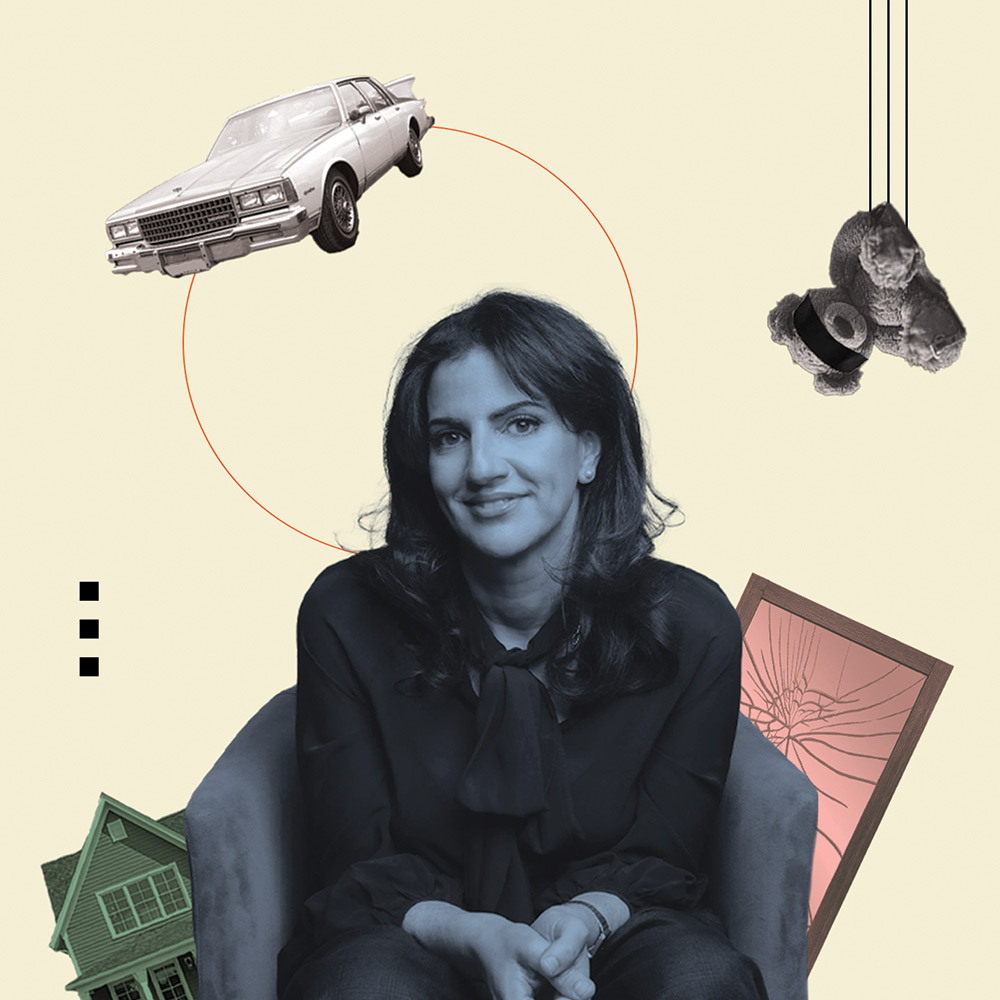

Taffy Brodesser-Akner’s Family Dramas.

Taffy Brodesser-Akner’s Family Dramas

In her latest novel, Long Island Compromise, the novelist explores how a kidnapping transforms a suburban New York family.

Taffy Brodesser-Akner’s new novel, Long Island Compromise, begins with a kidnapping. The year is 1980; Carl Fletcher, a wealthy Jewish factory owner living in the fictional Long Island town of Middle Rock, is getting into his car one morning when he suddenly finds himself blindfolded and hooded and then driven to an unknown location. Days later, with FBI agents gathered in the Fletchers’ living room, one of the kidnappers calls Carl’s wife, Ruth, and demands a ransom of $250,000. “I am a colonel in the organization known as the Caliphate Freedom Fighters of the Valley of Palestine,” he tells her. “We claim responsibility for the bombings in the JCC of Tulsa on February sixth and at the Hamish Middle School in Los Angeles on March first…. We have your Zionist scum husband.”

Books in review

Long Island Compromise: A Novel

Buy this bookWe find out later that it is doubtful whether either of these bombings actually happened. It is also unclear whether the Caliphate Freedom Fighters really exists and whether the kidnappers are who they say they are. Yet Ruth withdraws the $250,000 from the family account and drops it off at an airport as instructed. She does this with her youngest son, Bernard “Beamer” Fletcher, in tow. Carl is released soon after, but he is never quite the same: He’s been broken by the ordeal and becomes an almost catatonic figure in the Fletcher household—an absentee father to his three children despite his constant presence.

These events could constitute a novel in their own right. But this is just the opening episode of a long, multi-voice family drama about suburban New York life and the secrets it holds. One might expect a lot more action to come—further stories of conspiracy and crime and hardship—but though the opening has the makings of a movie as much as a novel, the rest of Long Island Compromise tends to direct its attention to the lingering effects of this initial event. Questions of wealth and class, Jewish identity, and family tensions are compellingly set up at the beginning but then fall away, or become muddled, by the end. Instead, we get a novel that leans heavily on backstory, in which flashbacks establish characters and single traumatic moments—even those that happened well before the characters were born—end up determining who they are.

The first thing you should know about the Fletchers is that each of them receives a payout of $500,000 to $750,000 per quarter because of the success of the family factory. They are not just middle-class suburbanites; they are rich, and their lives are defined by this wealth and privilege—by their large estate in Middle Rock and their brownstone in New York City, by their expensive educations and their ability to fail in their careers.

To help tell their story, Long Island Compromise is bracketed by short sections rendered in the collective voice of the townspeople of Middle Rock, but it is otherwise narrated in a close third person that follows the five recipients of these colossal sums: the three adult children and, briefly, their parents. In these sections, Brodesser-Akner guides us through the eventual yearlong fall of the younger Fletchers, which is apparently the result of the kidnapping—a calamitous series of events that includes, among other things, two major deaths, a conflagration at the family factory, and the discovery that the siblings have all managed to burn through their money, each in a different way.

Beamer Fletcher—the toddler taken on the ransom drop—is first up. It’s the present day, and Beamer lives in Los Angeles. After a childhood spent repressing the memories of his father’s kidnapping, he attends New York University and then becomes a hack screenwriter. His only successes thus far are cowriting credits on an action movie franchise about a kidnapping. When he has other ideas for scripts, they are also always about kidnappings (“Gone by dinnertime: a romantic comedy about a man who, years after graduation, kidnaps his high school crush without realizing it”).

Beamer’s writing is not the only way he works out his obsession with what happened to his father; he is also a sex addict who likes to be bound and humiliated by a dominatrix. The sex is mostly sexless, devoid of eroticism, and used to show that Beamer is spinning out of control. In Brodesser-Akner’s world, a healthy person would never want a weathered woman in a red wig and blue plastic bra, and with a conspicuously missing tooth, to stick an acrylic nail up his anus. For a lot of readers, perhaps less prudish, it might be more a situation of “to each his own.” Either way, Brodesser-Akner traces part of Beamer’s interest in BDSM to his wife, Noelle, a WASP from Maine whose sanitized blondness and dullness apparently no longer do all that much for him. “He now sought the opposite of Noelle,” Brodesser-Akner writes: “messy where Noelle was neat; dirty where Noelle was groomed; a sphincter that was warm and purple and inviting where Noelle’s was pink like a ballerina, hairless, puckered in rebuke, and just about sealed shut.”

Beamer’s section is the novel’s strongest. The reader gets a taste of contemporary Los Angeles, with its gurus and psychics and oily entertainment executives. Beamer is also a drug addict (one night at his house, his sister finds a bag filled with “a litany” of powders and amber bottles). He speeds toward his doom shoving every available substance into his system—uppers, Ambien, and expired nicotine patches, one of which he puts over his heart “for a soupçon of danger.”

Regrettably, the novel becomes less interesting as the narration changes its focus. Next up is the eldest son, Nathan, a soft-hearted land-use lawyer who has married a nice Jewish girl and stuck close to home. Nathan is a worrywart (because of trauma) who mismanages his money (because of trauma) and can’t say no to his wife’s desire to renovate their house (because of trauma).

Here is why he gets involved with a shady money manager named Mickey:

Mickey had been Nathan’s most ardent and zealous bully since they were first thrust together as children. It was the kind of cruelty that forged in them a friendship, with Nathan on the hamster wheel of trying to secure approbation and approval without ever really asking himself why. Such is the complicated stew of childhood friendships.

It all refers back, relentlessly, to childhood.

Nathan’s section does not crescendo with the same gusto as Beamer’s, though he has fumbled things just as badly. Then it is time to change protagonists again, and we are with the youngest fail-sibling, Jenny, who was born a few months after Carl’s kidnapping but has been ruined by it nonetheless. We are told throughout the novel that Jenny is a genius, but also apathetic and withdrawn. Whenever she witnesses family conflict, she doesn’t just check out; she falls asleep.

Jenny has been paralyzed by her family’s wealth, unable to decide on a career. Since she does not need to earn a living, what should she do with her life? One might suggest anything, but what she chooses instead is to do nothing. “It all felt small,” Brodesser-Akner writes of her plight. “Every single option just felt like it would lead to the life of an automaton.” Even when Jenny briefly becomes a labor organizer of graduate students at Yale, we can see that she is doing it not out of any moral imperative or genuine interest, but to make friends. This section takes up most of the final third of the book, yet it contains no momentum; Jenny mostly sleeps through it.

Finally, Ruth arrives to fill in the blanks in the family history, but by this point, everything has been rehashed ad nauseam. The secrets that Ruth reveals feel minor—and when the focus is briefly on Carl, we get even less. Even the disclosure of who was actually behind the kidnapping all those years ago manages to land with a thud. How can a book with so much ostensible action feel so slack?

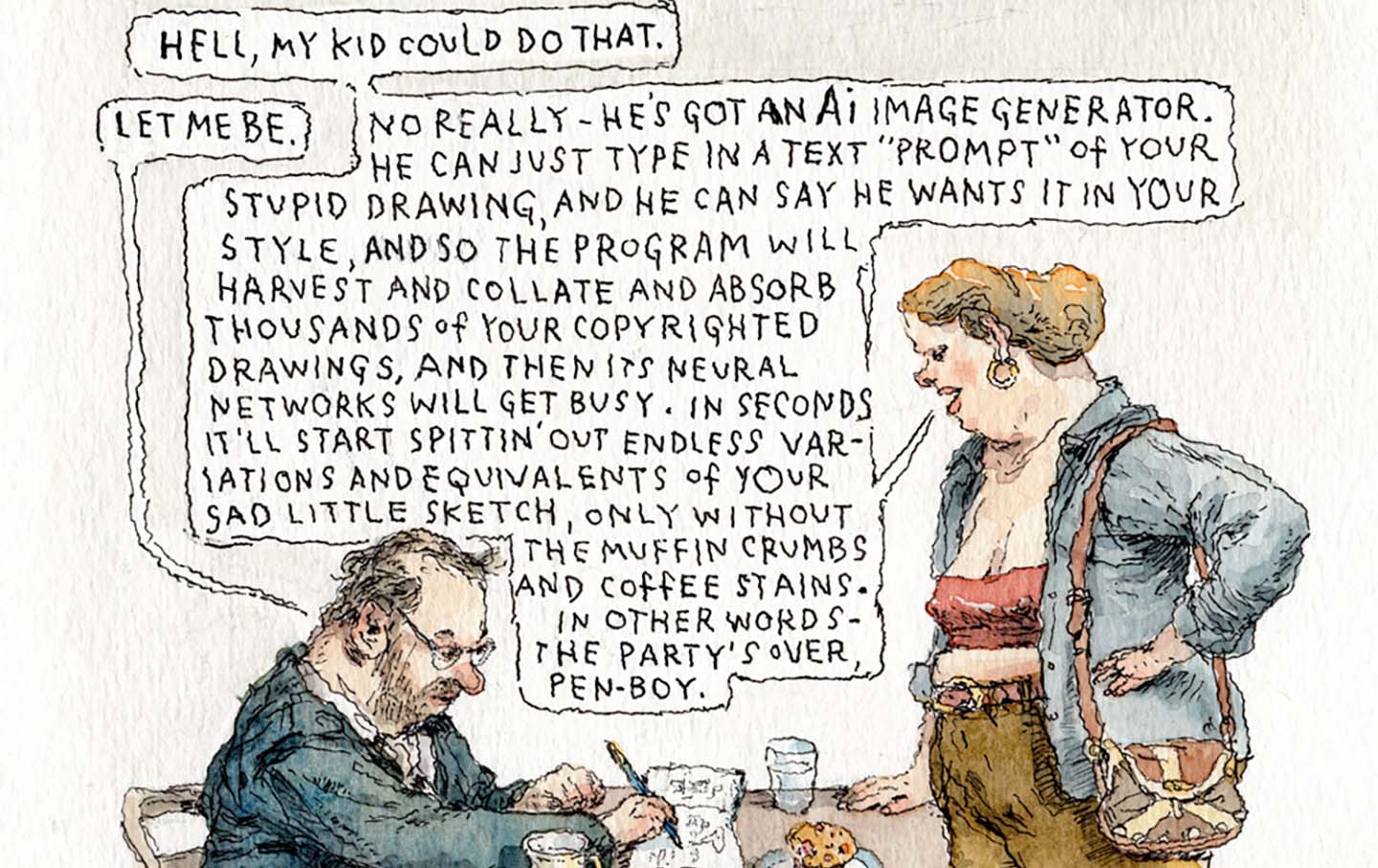

In a 2021 essay in The New Yorker, Parul Sehgal sketched a portrait of the contemporary novel and its tendency to lean on what she refers to as the “trauma plot.” The essay pointed out the problems created by relying on a traumatic backstory to serve as a novel’s main engine and source of narrative propulsion. “Unlike the marriage plot, the trauma plot does not direct our curiosity toward the future (Will they or won’t they?) but back into the past (What happened to her?).”

Brodesser-Akner’s first book, the critically acclaimed Fleishman Is in Trouble (2019), was the embodiment of a “What happened to her?” novel. In it, a high-achieving mother on Manhattan’s Upper East Side named Rachel Fleishman disappears, leaving her soon-to-be-ex-husband, Toby, with their kids for a few weeks one summer. Toby wanders around the city, sexting with women he has met on hookup apps and intermittently wondering about Rachel’s whereabouts. Rachel, he reflects, was never actually all that great as a mother; she was a harsh and volatile person, a workaholic who has saddled him, a lowly Manhattan hepatologist (or so we are told), with their kids.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →The book is cleverly narrated not by either of the Fleishmans but by Toby’s friend Libby, a former writer for a men’s magazine who has taken a voyeuristic interest in the couple’s breakup. This device goes a long way toward explaining some of the book’s more far-fetched moments. Libby idolizes the work of a venerable Gay Talese–esque writer at her old magazine, and so her interest in the minutiae of Toby’s sex life makes sense. But then she gradually learns the history of the Fleishmans’ relationship, which becomes far more important than the question we started out with (where is Rachel anyway?), which seems at moments not to matter at all. It turns out that Toby’s account of things may not be all that accurate. But at the core of what did happen was a traumatic event: Libby discovers that Rachel had a terrible experience giving birth to her first child, and this prevented her from settling into motherhood. Without Rachel’s consent, Libby learns, an aggressive doctor forcibly broke her water so that she had to give birth that day. This is rendered vividly: “She screamed as a lightning pain tore into her body, and still his hand was up inside her, needling at something, and manipulating, until finally he pulled his hand out.”

Brodesser-Akner is interested in the rarefied worlds of the upper classes—the Manhattan private-school set in Fleishman, the gated estates of suburbia in Long Island Compromise. These books aspire to the comedic, yet though they have their moments of crisp social observation and witheringly accurate detail, they are not quite satire. Any criticism of the way the rich live is defanged by the same explanation over and over: These rich people live this way because someone hurt them.

If Fleishman Is in Trouble is the epitome of the “What happened to her?” novel, a book about the pain that women suffer under patriarchy, then Long Island Compromise could be fairly called a “What happened to them?” novel, a book about the foundational trauma that forever shapes a family’s dynamic. Just as Sehgal warned, even the splashiest elements of the plot begin to feel oddly inconsequential in the face of such trauma. The tension of the novel dissipates; the impression increasingly becomes that everything that matters to these characters has already happened. So what compels the reader to continue?

Stripped of any uncertainty, Long Island Compromise limps to its drawn-out close, but it really could have ended the moment that poor papa Fletcher was kidnapped. Now that the main event has passed, all that is left for the Fletchers is to find homeostasis. And that is what Brodesser-Akner provides us with: We learn the fate of every single character, even extremely minor ones (an erstwhile Middle Rock cello prodigy now has arthritis; Beamer’s dominatrix is still blithely tying people up). The Fletcher kids come to realize that they are “bound by only one tether, which was what happened to them.” Brodesser-Akner is a magazine writer, and both of her books have a tendency to spell out their themes throughout and then linger in a long explanation at the end. It’s an essayist’s impulse, perhaps: to formally tell one’s readers what you’ve been telling them throughout.

“Maybe that was the real Long Island Compromise,” Brodesser-Akner writes near the novel’s end. “That you can be successful on your own steam or you can be a basket case, and whichever you are is determined by the circumstances into which you were born.” There are several more pages of this, stating and restating what the events of the book have already shown. Here again is the problem of the novel as a message-delivery service: It gives the reader no credit.

The insistence that everything that happens, every decision that one makes, can be traced back to a tortured history is not just a faulty narrative device; it keeps the book, and its characters, from achieving real depth. A recurring motif in Long Island Compromise is the idea of the dybbuk, a spirit from Jewish folklore that Brodesser-Akner describes as a “miserable soul that cannot progress to a heavenly rest and instead stays on Earth and takes over somebody’s body.” The dybbuk is initially used as a metaphor for Carl’s kidnapping, but we find out late in the book that it also refers to a young Jewish chemist that Carl’s father murdered while escaping the Nazis. This is the novel’s dark reveal: Oops, it was the Holocaust haunting them all along.

The rabbi at one character’s funeral says, “The Fletchers are a great Jewish American family…. They had to invent who they were. What a Jew could be in America.” But the insights about the Jewish experience and what a Jew can be feel tacked on and belated, and it is hard for the reader to connect the bad behavior of the Fletcher children with the Holocaust. The book is not a study of Jewish trauma, as it sometimes implies, but of a single family’s trauma and the ways it supposedly—though not always convincingly—shaped their lives. By the end, we don’t have a picture of who the Fletchers are but rather a picture of what they have suffered, and the book seems to be saying that these are the same thing: You are your hardships. It’s an old idea, but is it true?